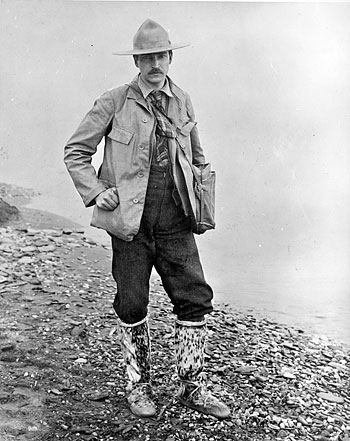

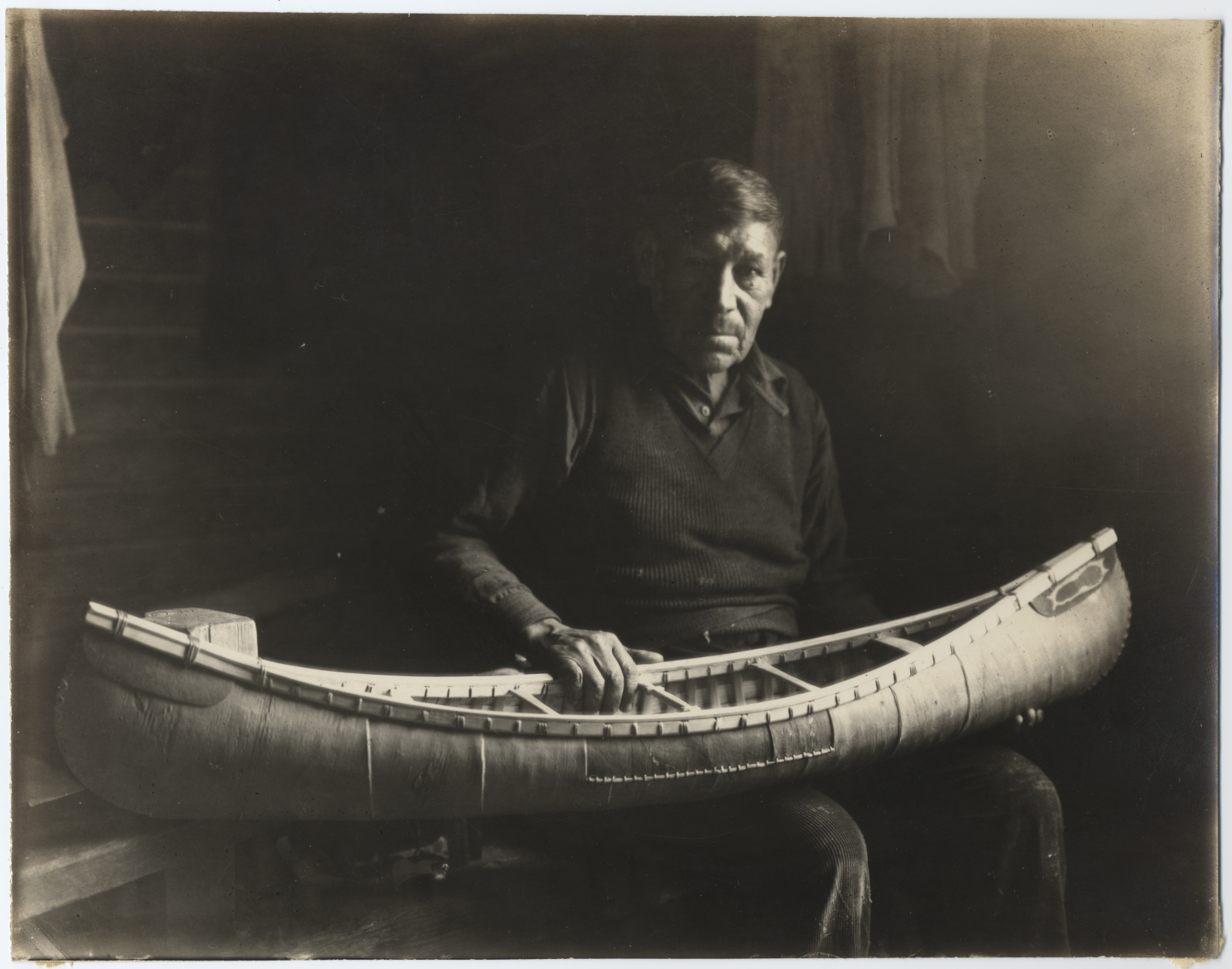

Welcome to one of the Interpretation Department’s obsessions! The Edwin Tappan Adney collection at The Mariners’ Museum and Park include 120 canoe models. Adney lived from 1868-1950. He was from the United States but fell in love with canoes when he was on vacation in Canada at the age of 19. For Adney, building canoe models was not a hobby. He felt that it was his duty to document as many of the boats as he could. The models were made ¼ sized and sometimes ⅕ sized. He learned some of the building methods from Native builders. For example, Frank Atwin, Passamaquoddy, was one of his teachers. This is an outstanding photograph, showing the size of the models.

Adney’s plan was to use the models to illustrate a book about the canoes. Unfortunately, the Depression meant that there were no backers for his idea. He then attempted to sell the models to several different museums, but again, he had no takers. Adney ended up using them as collateral for a $1,000 loan. The Museum’s buyers heard about this, paid off the loan and the $424 interest (!). Upon his death, Adney’s son donated all his papers, notes, sketches, and writings to the Museum.

From Erika Cosme:

This Adney model from our Collection was built in 1931 and represents the birch bark canoe, used in the Athabascan culture for hundreds of years. The Athabascan Indigenous culture extends from Alaska into parts of Canada and the Northern United States where birch trees are native. Birch was a great boat building material for the native people.

The bark was used as the outer skin of the canoe. The boatbuilders would cut down birch trees, and shave off long strips of the bark, which would be attached to the ribs and hull of the canoe. The ribs holding the boat together were often made from cedarwood. The final look of the design is a long, flat bottom, with wide sides that sharply narrow at the bow and stern. To help keep them waterproof and prevent any water from getting into the canoe, the seams of the boat would have been sealed with pitch, a tar-like substance made from the tree sap of a spruce tree.

This side view is a great angle to show the gunwales. This portion of the boatbuilding was typically done by the women, as was patchwork and repairing. Although a popular and useful type of canoe, Adney notes that his model represents an ancient and long discontinued form. As better manufacturing materials became available, and a higher demand for these canoes was made as Europeans moved into the Athabascan territory, the Athabascan people could not keep up with production.

From Emily Clause:

Adney’s model of a Tête de Boule canoe showcases the type of birch bark canoe that the Tête de Boule people used in their daily lives and constructed for French fur traders at the height of the fur trade in North America. Similar to the Athabascan people, the Tête de Boule lived in an area where they had access to superior birch bark. This, in combination with the high demand for canoes from French fur traders, meant that many of the Tête de Boule were experts in the construction of birch bark canoes.

The Tête de Boule, or Atikamekw as they are also known, lived in the upper Saint-Maurice River Valley of Quebec. The area they inhabited is ancestral land they called Nitaskinan, which translates to Our Land. The Tête de Boule people still live in this area today with about four to five thousand living on the three reserves: Manawan, Opticiwan, and Wemotaci. The name Tête de Boule originated from French fur traders who recognized that these native people cut their hair short, unlike other native people who traditionally kept their hair long. Thus Tête de Boule, meaning round head or ball head, came about.

The construction of Tête de Boule birch bark canoes is similar to that of the Athabascan birch bark canoe. The reason that birch bark was the best material for canoes is that it is flat, hard, lightweight, and could be waterproofed. The frame of the canoe was built from planks of cedar, joints were sewn together with roots from pine or spruce trees, and the outside skin of the canoe was made from birch bark. In comparison to the canoes of other native people, the Tête de Boule canoe was generally narrower on the bottom. The bottom of the canoe was mostly flat with an upwards curve at the stern and bow of the canoe.

Historically, the Tête de Boule canoe played a significant role in fueling the North American fur trade. Beginning in the 17th century the French began to hire the Tête de Boule people to both build and paddle canoes. Canoes became so important to the fur trade that the French even established the world’s first canoe factory at Trois-Rivieres, Quebec, in 1750. When the fur trade began to decline in the 19th century, the use of the canoe lessened, but native people were continually hired by fur trading companies like the Hudson’s Bay Company.

From Marc Nucup:

The Beothuk of Newfoundland used their bark canoes in the coastal waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The canoe, or japathuk, had tall sides that allowed it to weather Atlantic swells and waves. The cut-outs at the front and rear of the boat still allowed for two paddlers to reach the water with ease. The 20-foot V-shaped hull, however, required ballast stones to keep it steady. Besides hunting marine birds, seals, and dolphins, the Beothuk could chase and harass small whales to the beach. The ancestors of the Beothuk may have been the skraelings of Norse epic, meaning they could have inhabited Newfoundland for more than 600 years before European settlement in 1610. The community struggled as colonization forced them away from the coast. The last documented member of the tribe died in 1829.

From Lauren Furey:

The Wolastoqiyik, meaning “people of the beautiful river” in their own language, have long resided along the Saint John River in New Brunswick, Maine, and the St. Lawrence River in Quebec. Historically, the Europeans referred to the Wolastoqiyik by a Mi’kmaq word, “Maliseet,” roughly translating to English as “broken talkers.” According to the Mi’kmaq, the Wolastoqiyik language was a broken version of their own. Their language is considered part of the Eastern Algonquian language family which also includes the Mi’kmaq, Abenaki, Passamaquoddy, and the Penobscot.

The Maliseet included three different types of canoes in their culture: birch bark, canvas, and moose hide. Canvas would have been adopted after contact with the Europeans. This model is actually constructed from deer hide, as Adney found it was easier to work with because it wasn’t as bulky as moose hide would have been. Rawhide was used for attaching the hide to the gunwales. This model is 32” long, 10” wide, and 6” deep. On the actual canoes, the hide was “frost tanned” using soap and water, freezing, and scraping while frozen.

Today there are six Wolastoqiyik Maritime communities in Canada and one in Maine. In the 2016 census, 7,635 people identified as having Wolastoqiyik ancestry.

From Wisteria Perry:

Mi’kmaq (pronounced “meeg mah”), also known as the MicMac, were among the first peoples to interact with European explorers and traders and were the original inhabitants of the Atlantic Provinces of Canada. Today, the Mi’kmaq live throughout Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, Newfoundland, Maine, and the Boston, Massachusetts, area. They were known to have several different types of birch bark canoes — some made for navigating rivers and lakes, while others were meant for sea-going, capable of traveling long distances.

Mi’kmaq Restigouche Rough Water Birchbark Canoe is an example of one of those river traveling canoes. Based on a Mi’kmaq canoe at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in New Brunswick, this model was built in 1926. It is 50.5 inches long or ⅕ the size of the actual canoe. The use of birchbark made the canoe light, seaworthy, and easy to repair. The Mi’kmaq hunted seals, moose, caribou, beaver, bear, smelt, herring, migratory birds, eels, and shellfish. These boats are still used today on the Restigouche River, which is known for salmon.

You can learn more on our website! Just follow the link and search “Adney”. You’ll be able to see many of the models as well as some of the sketches, smaller pieces, and books in the Museum’s Collection.

https://catalogs.marinersmuseum.org/search