The Virginia Peninsula was already engaged in wartime work when President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war against Germany on April 6, 1917. Local military bases, shipyards, air fields, ports, and people turned their faces toward the nation’s crusade to make the world safe for democracy.

Headquarters, Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation

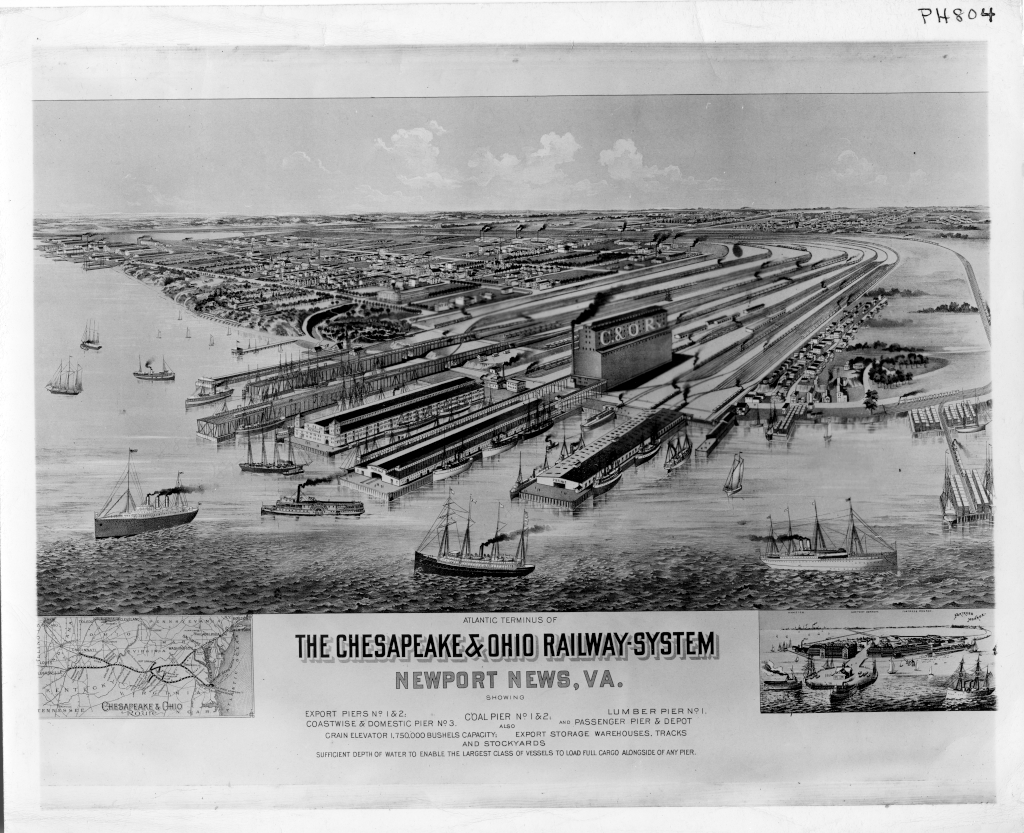

The US Army, in anticipation of America’s entry into the war, surveyed the Hampton Roads area in early 1917 to ascertain where to establish a port of embarkation. Newport News was selected over Norfolk as headquarters for the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation. Several geographical reasons influenced that decision. Norfolk was a congested port and already the center for many naval activities. Newport News offered good port facilities, a large harbor, excellent railroad connections, ship repair opportunities, and an abundance of available land.

The Army assumed operations of the port from the C & O Railroad in July 1917 and immediately began the construction of embarkation camps. The Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation was one of only two military ports (New York City was the other) created to ship doughboys overseas. In less than two years, 145 transports moved 261,820 soldiers from Newport News to France.

Colonel (later brigadier general) Grote Hutchinson was named commander of the port. He established his headquarters in the federal building in downtown Newport News. Camps were also needed in the outlying countryside to station and train men prior to shipment overseas. Thus, the Army acquired large tracts of property in Warwick County from the Old Dominion Land Company to build five troop cantonments.

Camp Stuart

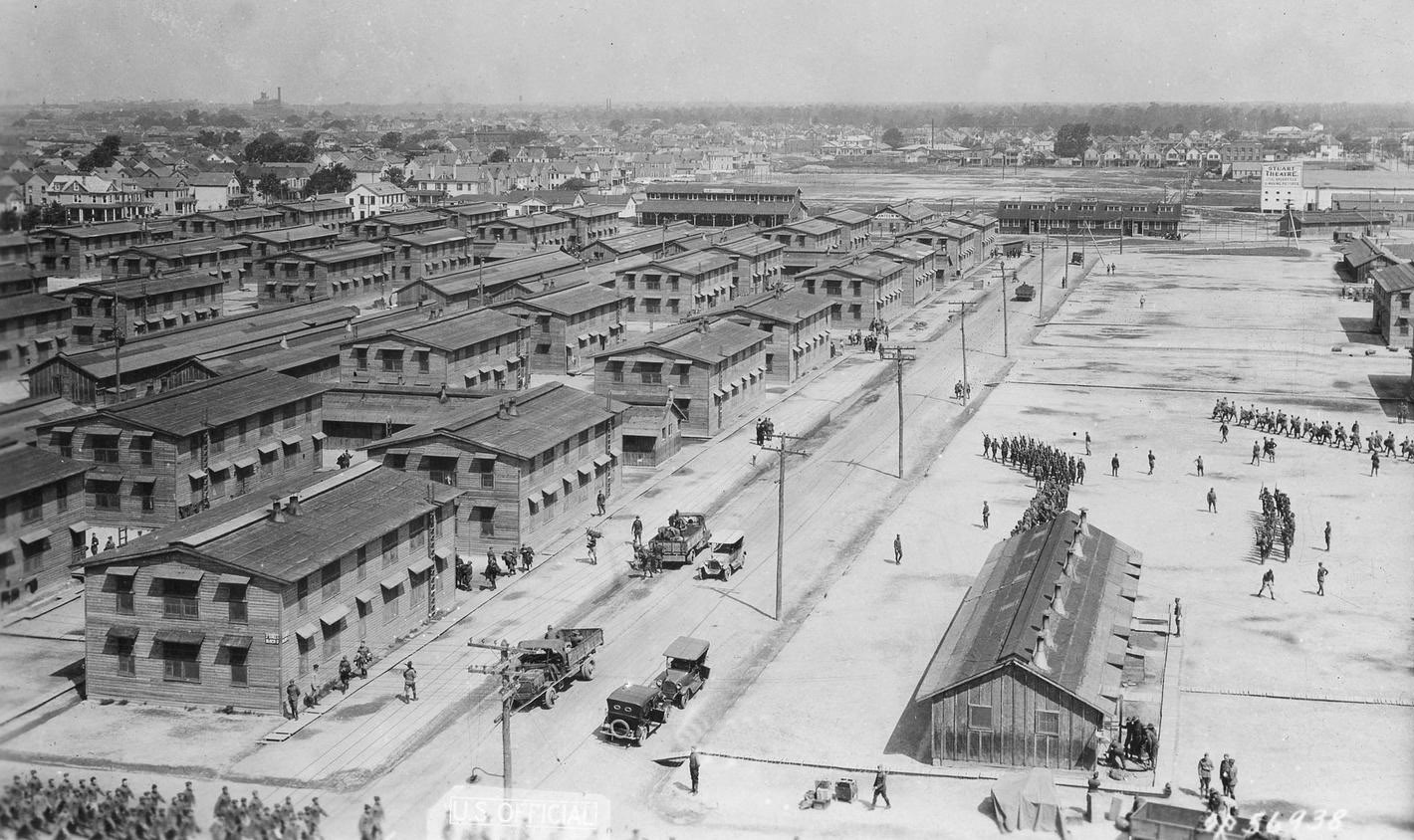

Named for Confederate general J.E.B. Stuart, Camp Stuart was constructed on a 309-acre tract overlooking Hampton Roads. It was the Army’s largest embarkation camp during the war with almost 115,000 soldiers passing through en route to Europe. Hastily built between July and December 1917, Camp Stuart consisted of row after row of barracks, mess halls, and other support structures including a huge 50-ward hospital.

Camp Hill

Camp Hill was constructed simultaneously with Camp Stuart. It was another exceptionally large installation covering acreage along the James River from Sixty-fourth Street to Newport News’s Huntington Park. The combined cost of these camps reached nearly $16 million. Like Camp Stuart, Camp Hill was also named for a Confederate general, A.P. Hill. Many military camps and bases throughout the South were named in honor of Confederate leaders. This tradition was instituted by the Army to alleviate any lingering bitterness in the South remaining from the Civil War and the Reconstruction era.

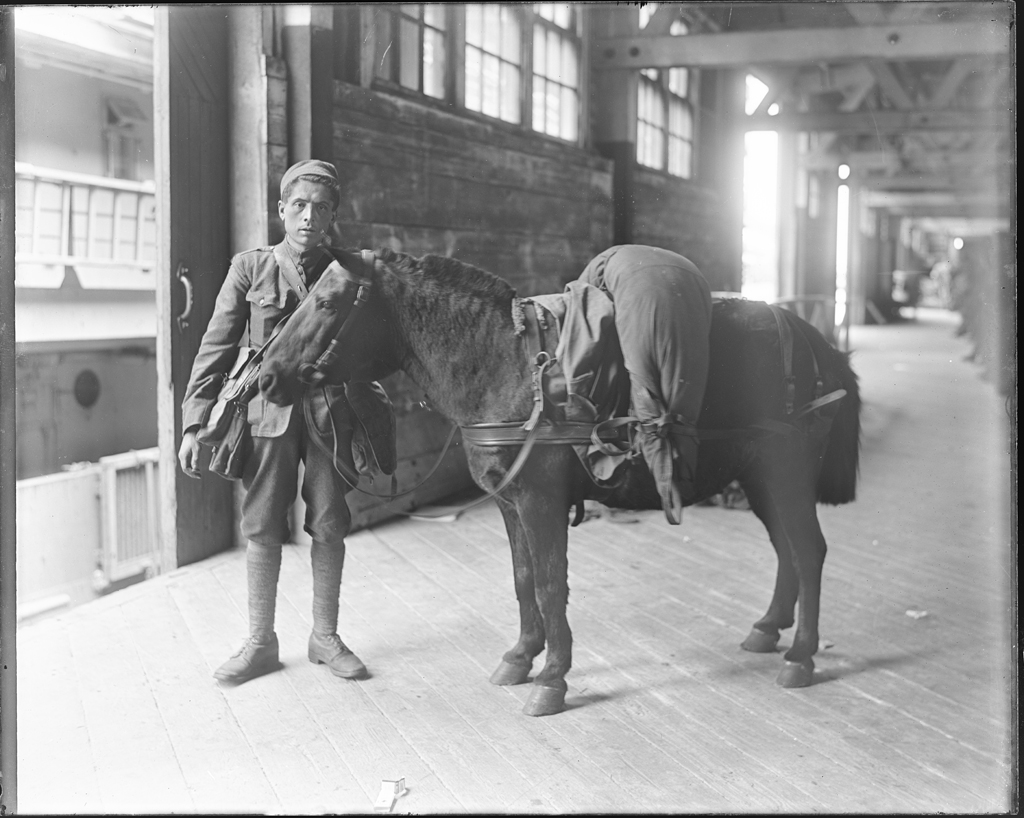

Camp Hill sent 63,887 men overseas. While the camp served as the port’s center for the Motor Truck Corps, it played an even greater role as the animal embarkation area. Camp Hill’s large veterinary hospital and livestock pen required 900 men to care for the horses and mules. The camp’s capacity was 10,000 animals. A total of 33,704 horses and 24,474 mules were shipped overseas through this camp. These animals consumed tremendous amounts of feed annually: 82,870,000 pounds of hay, 41,392,000 pounds of oats, and 7,273 pounds of bran.

Camp Alexander

The vast quantities of animals and supplies processed through the port prompted the Army to billet several African American stevedore and labor battalions at Camp Hill. This resulted in several incidents between Black and white soldiers. In particular, the quarters provided for African American soldiers proved to be inadequate. They suffered terribly during the winter of 1917-18. As many as 20 to 30 men were assigned to a tent. There were few blankets, heat was provided by open fires, and food was served outdoors.

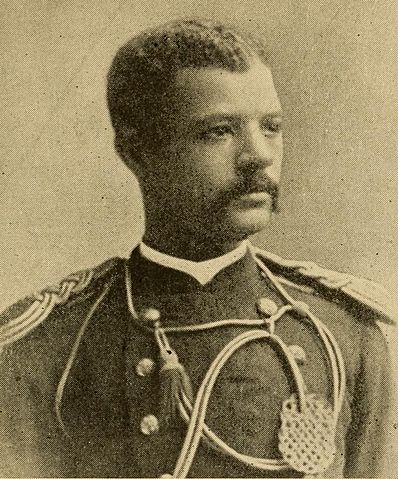

The Army sought to correct these problems and constructed Camp Alexander to house African American labor battalions. Named in honor of Lieutenant John Hanks Alexander of the 6th US Cavalry, one of the first African American West Point graduates, Camp Alexander was completed in August 1918, It was located at the northeastern portion of Camp Hill along the C & O tracks. A total of 57,081 African Americans embarked from Camp Alexander.

Camp Morrison

An Air Service depot was organized along the C & O tracks in the Gum Grove section of Warwick County. The 295-acre site was named for Colonel J.S. Morrison, construction engineer of the Peninsula Division of the C & O Railroad. Camp Morrison served as the embarkation center for balloon units and aero squadrons. More than 10,000 men were processed through Camp Morrison en route to France. The camp included 24 warehouses built for storage of aviation equipment and supplies.

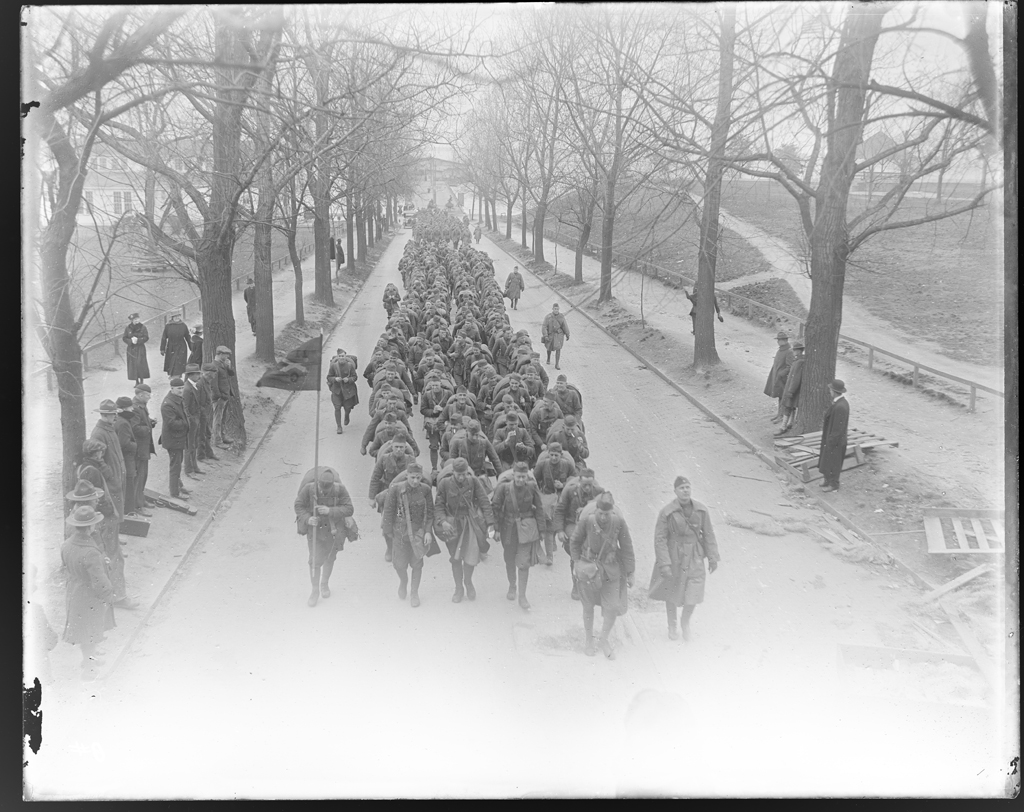

Endless Treads of the Soldiers’ Boots

The entire Peninsula was teaming with troops by summer 1918. Camp Stuart became the largest embarkation camp, both in size and number of troops processed, in the United States. In August 1918, a total of 46,130 men left Newport News aboard 31 vessels bound for France. Initially, the soldiers marched to their transports at night in order to avoid information leaks. Such secrecy was soon deemed unnecessary and units marched in grand parades, complete with bands playing martial music all the way to the piers.

Thomas Wolfe, a worker at Langley Field and Newport News Shipyard, wrote about the endless movement of troops in his book, Look Homeward, Angel:

“Twice a week the troops went through. They stood densely in brown and weary thousands on the pier while a council of officers, tabled at the gangways, went through clearance papers. Then, each below the sweating torture of his pack, they were filed from the hot furnace of the pier into the hotter prison of the ship. The great ships, with their motley jagged patches of deception, waited in the stream; they slid in and out in unending squadrons.”

Private Herbert G. Smith, later a Newport News judge, vividly remembered the arduous march from Camp Hill to the C & O piers. Smith said that it was “the hottest day I ever saw in my life. My colonel knew I was from Newport News and asked me when we got to Washington Avenue and Twenty-eighth Street, how much further it was. I said, ‘you just as well to keep walking now, we’re almost there.’” Instead, the commander stopped his regiment for a brief rest, and Smith recounted “he laid down on the street car tracks right in the middle of Washington Avenue and rested that morning.”

An Armed Camp

The Peninsula became one of the largest concentrations of military activity in the United States. Permanent installations, like Fort Monroe and Langley Field, expanded efforts to train and protect the lower Chesapeake Bay. Besides the four primary Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation camps, numerous other installations were created to support the war effort.

Camp Eustis, named for War of 1812 hero Bvt. Brigadier General Abraham Eustis, primarily serving as a coast artillery and observation balloon training base, was also utilized as an embarkation point for 20,000 men assigned to artillery and motor transport units. Other installations, such as the Yorktown Navy Mine Depot, were hurriedly constructed to support training and to organize war materiel required to wage war in Europe. Both the Yorktown Depot and Camp Eustis had special spur tracks constructed to facilitate the movement of troops and materiel.

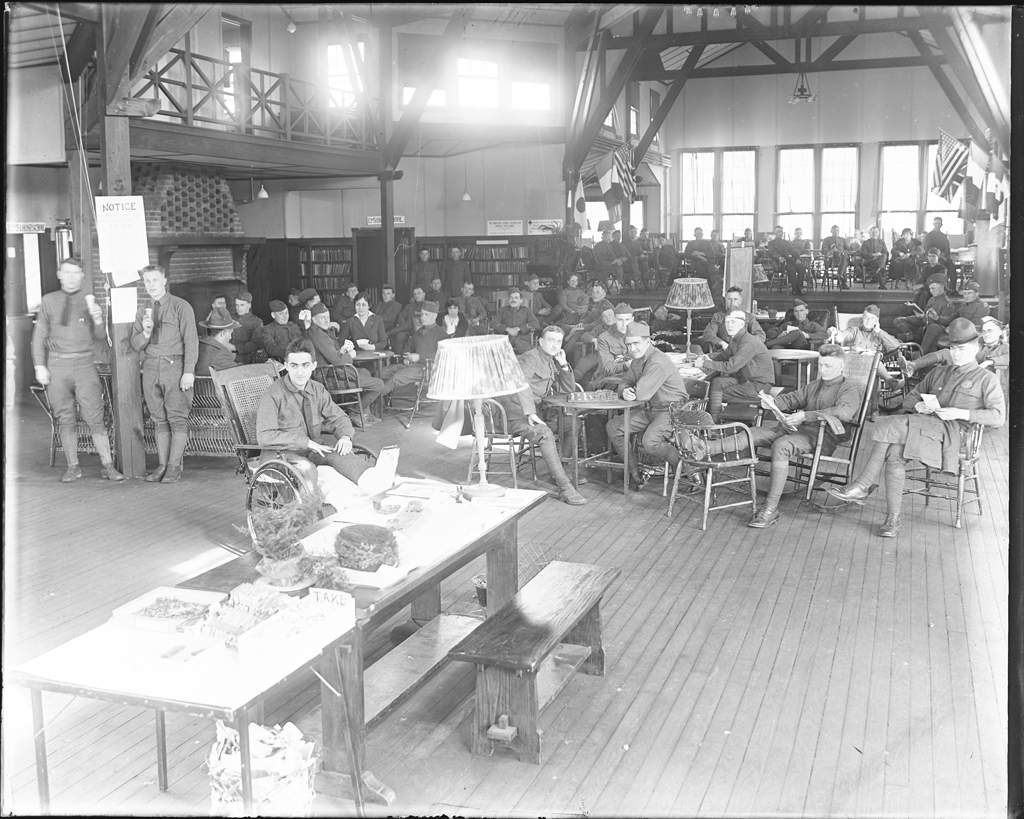

Support for the Soldiers

Numerous organizations established facilities catering to the social, physical, mental, recreational, and moral well-being of the almost overwhelming influx of soldiers on the Virginia Peninsula. The entire community went out of its way to make the soldiers feel at home. During a single month in 1919, the Newport News YMCA provided 2,200 baths, slept 2,475, served 6,000 meals, mailed home $5,675, checked 2,385 parcels, and provided two pool tables where 486 hours of pool were played. A total of 26,255 men used the building. YMCA work was so important to the Newport News community. Thousands of soldiers virtually overwhelmed local volunteers. Consequently, the National War Work Council of the National YMCA had to supplement activities on the Peninsula.

The YMCA opened tent facilities at each embarkation camp until more adequate buildings could be erected. Eventually 10 entertainment huts were constructed: one at camps Morrison, Hill, and Alexander, as well as seven in Camp Stuart (five for whites and two for Blacks). A main facility was built on the Casino Grounds on the James River in downtown Newport News. The YMCA invested over $200,000 constructing, maintaining, and equipping these buildings.

Dance the Night Away

Dances were by far one of the most popular forms of entertainment. The YMCA reported it was often “hard to get enough girls” out to the remote camps like Camp Eustis. The Peninsula had been “doing the Dance of Death” for more than a year. Many citizens considered it their patriotic duty to volunteer. Even though the dances were chaperoned by grandmothers and married matrons, there were numerous cases of unchaperoned liaisons that resulted in a number of cases of venereal disease. Public health officials quickly tried to mitigate the problem. A free clinic and a home for “wayward, helpless, and straying girls” were established in downtown Newport News.

United War Work

The Red Cross, Salvation Army, Jewish Welfare Board, American Library Association, and the Women’s Service League were some of the other associations that attended to the needs of the servicemen. It seemed everyone was busy helping soldiers. The owners of movie theaters in downtown Newport News provided free films on Sundays. The Jewish Welfare Board raised $70,000 for war work. These dollars were used to distribute 60,000 letterheads, 30,000 envelopes, and 10,700 packages of cigarettes at Camp Stuart’s hospital. Workers of the Jewish Welfare Board met 76 transports filled with troops and distributed 45,970 handkerchiefs and a countless quantity of matches, chewing gum, and cigarettes.

The Red Cross was perhaps one of the most active humanitarian organizations during the war. The Newport News Chapter was organized on June 2, 1917, and its members assumed the herculean task of providing canteen services for the troops moving through the port. The canteen’s primary purpose was distributing coffee, cake, chocolate, cigarettes, and other supplies to soldiers as they boarded transports, day and night. On June 18, 1918, nearly 8,000 men were fed between 4 a.m. and daylight.

The War is Over, ‘Over There’

When the Armistice ending the war was declared on November 11, 1918, a mixed sense of pride and relief was felt across the Peninsula. There was; however, little time to reflect upon peace. The embarkation camps were immediately transformed into reception centers welcoming home the doughboys.

Battle of Newport News

The Armistice Day celebrations in Newport News resulted in chaos. The day began as a jubilant occurrence, commemorated by an afternoon parade down Washington Avenue. More than 1,000 soldiers from camps Eustis, Morrison, and Stuart participated in the parade, and as they marched through town, they were heckled by some of the onlookers as “tin soldiers.” These taunts and jeers angered the soldiers, many of whom were already disappointed not to have had the chance to see action on the front. Some were simply disenchanted with several downtown merchants who had engaged in war profiteering and price gouging at the expense of the doughboys. Following the parade, the stage was set for the “Battle of Newport News,” when the soldiers received overnight passes. The men immediately returned to Newport News to enact their revenge.

Washington Avenue Melee

Thousands of soldiers descended upon downtown Newport News at nightfall and immediately turned Washington Avenue into a war zone. Local police were powerless to stop the riot centering on various shops that had overcharged soldiers. The enraged troops broke windows, looted stores, and generally caused mayhem. Pawnbrokers’ signs were used as bowling balls, and barber shops’ poles were turned into battering rams against shop doors that did not open quickly. The Jem Cigar Store suffered the destruction of $1,000 worth of goods, and witnesses watched soldiers dump candy in the street. The Palace Restaurant was virtually demolished.

Trolley service was suspended. A giant bonfire was lit in the center of Washington Avenue and fed with anything flammable the soldiers could find. The riot ended thanks to a wise tactical move by an Army major. A rumor was spread about a large fight between civilians and soldiers across the Twenty-eighth Street Bridge. When the marauders arrived on the other side of the bridge, they were met by 300 military police, who closed off the bridge behind them. Order was finally restored.

“Newport News Blues”

The riot was quickly forgotten despite the considerable damage along Washington Avenue. The soldiers were satisfied that they had survived suffering “the siege of Newport News.” Civilians cleaned up the streets and then simply redoubled their efforts at hospitality. While one poem was circulated declaring Newport News “the rottenest hole the wide world through,” a popular song, “Newport News Blues,” was written to express more of the homesick feelings the soldiers shared:

Oh! Newport News is the latest fad.

Newport News Blues will surely drive you mad,

You start into jazz – then you raz-ma-taz-

Oh, way down south–in the land of cotton,

Your Uncle Sam has not forgotten,

You’re a-way–a-way far a-way from Broadway–

They sing and dance that haunting mel-o-dy-

Oh! When you’re down in Newport News,

What do they want to play that doggone blues for?

The blues of Newport News…–Oh! News.

Glorious Return

The first transport ships from Europe began arriving in mid-December 1918. When the USS Nansemond arrived on March 14, 1919, “the cheers of the men on board could be heard for several miles.” Each ship was greeted by two brass bands playing patriotic melodies. The scene would be repeated hundreds of times during 1919 as the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation welcomed home almost a half a million doughboys.

Numerous Allied troops, including New Zealanders and Australians, passed through Newport News en route home. There were unusual soldiers as well, such as the members of the Czech Legion, former members of the Austro-Hungarian Army, who, once captured, exchanged their POW status and fought in the Russian Army. The Russian Revolution ended WWI on the Eastern Front and caused the Czech Legion to move across Russia, often fighting the newly formed Red Army across Siberia to Vladivostok. The legion’s stop in Newport News on July 20, 1919, was just a part of their long journey home.

Welcome Home

A Welcome Home Committee was established by the Newport News Chamber of Commerce shortly after the Armistice. The committee sought to coordinate the activities of civic associations in greeting all transports. Whenever a transport arrived, church bells rang, and groups of school children were sent to wave flags and cheer as the soldiers marched from the pier to the camps.

Red Cross Canteen and War Community Service volunteers were always on hand to pass out refreshments and cigarettes. The Red Cross Canteen fed 422,253 debarking soldiers while also handling 50,000 sick and wounded which required extra duty.

Several states utilized buildings on the Casino Grounds to provide a true welcome home to their units returning through Newport News. Volunteers placed state flags along the road to Camp Stuart. Soldiers could pick up mail and news from home. Telegrams were sent to newspapers back home announcing the safe arrival of their local heroes.

Victory Arch

On January 6, 1919, the Newport News Chamber of Commerce developed plans to build an “Arch of Triumph” at the intersection of West Avenue and Twenty-sixth Street. Newport News City Council supported the concept, and a Central Community Committee was established. The committee immediately recognized that there was insufficient time and money available to construct the proposed permanent memorial. Therefore, a design by Ralph Preas, a Newport News shipyard draftsman, based on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, was agreed upon.

Construction of the Victory Arch, as it became known, began on January 27, 1919. Preas’s plans called for a 50-foot-wide structure with two 16-foot-square bases and an 18-foot-wide-span. The arch appeared massive, but was totally hollow, being fabricated of brick and wood with a plaster facade. Private donations, totaling $6,081.07, were used to construct the arch.

The arch was formally donated to the City of Newport News on April 13, 1919. It was inscribed with the words, “Greetings with love to those who return; a triumph with tears to those who sleep, ” written by shipyard attorney Robert G. Bickford. The Palm Sunday dedication was a gala affair, complete with more than 5,000 school children waving small flags. They were all dressed in white and lined up on the Casino Grounds to spell out “Welcome.”

After Mayor Samuel R. Buxton spoke, the ceremony culminated with four local Boy Scouts unveiling the arch’s inscription. The Daily Press editorialized, “The Arch will stand as the guiding light to those who yet are coming here from war, to greet them as they pass on their glorious return.”

Return of Local Heroes of the 29th Division

The largest ceremony planned at the Victory Arch was the commemoration of the return of local members of the 29th Infantry Division on May 20, 1919. The Huntington Rifles were the first to return to the Peninsula and the first to march through the Arch. The parade was halted on several occasions when spectators rushed out into the street to embrace their loved ones.

An even greater patriotic event was the triumphant return of Battery D on May 25, 1919. It was called the “biggest event ever pulled off in Newport News.” A flotilla of tugs and other small craft greeted the USS Virginia as it neared Newport News Point and then escorted the transport to the C & O piers. The troops debarked under the strains of ship whistles and military bands and marched toward the Victory Arch between columns bedecked with flags and victory laurels. Truckloads of young ladies strewed rose petals before the troops. At a grandstand erected outside the Federal Building, Governor Westmoreland Davis, Secretary of the Treasury Carter Glass, Congressman Otis S. Bland, and Mayor A.A. Moss welcomed the soldiers home.

Final Ceremonies

On September 19, 1919, two more ceremonies were held at the Victory Arch by the Welcome Home Committee to honor Newport News’s servicemen. The first acknowledged veterans who returned with a commemorative Newport News World War I Victory Medal. A similar, but separate program was held at the Red Circle Club on Marshall Avenue at Twenty-fifth Street to honor African American veterans.

The second ceremony at the Victory Arch that day, expressed public gratitude to those soldiers who made “the splendid sacrifice” during the war. Thousands of people attended a solemn tribute that afternoon, which ended with the unveiling of an engraved bronze memorial tablet listing 32 of Newport News’s fallen heroes. Once “Taps” was sounded by the bugle, all of the soldiers in attendance clasped their hands and pledged to “keep the country safe from all forces of evil for the sake of those who slept in Flanders Field.”

Closure

By the end of August 1919, all of the temporary camps had closed, and the area slowly returned to its prewar lifestyle. The Virginia Peninsula had proven itself time and time again during the war. It was able to provide the ships, manpower, training, sacrifice, and compassion to serve as the leading military community in the United States. This commitment truly helped the nation achieve victory.

References

Quarstein, John V. Hilton Village: America’s First Public Planned Community. Staunton, Virginia: American History Press, 2017.

Quarstein, John V. and Parke S. Rouse Jr. Newport News: A Centennial History. Newport News, Virginia: City of Newport News. 1996.

Quarstein, John V. World War I On the Virginia Peninsula. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 1998.