The Medal of Honor was established in 1862 to honor soldiers and sailors who served beyond the call of duty. It is the United States’ highest military decoration. Battle flags were such significant fixtures on Civil War battlefields for both Union and Confederate armies, and many recipients were awarded their medals for defending or capturing a flag. Twenty-six Medal of Honor awards were conferred upon African American service members during the Civil War. Eight were presented to naval personnel, the rest to soldiers.

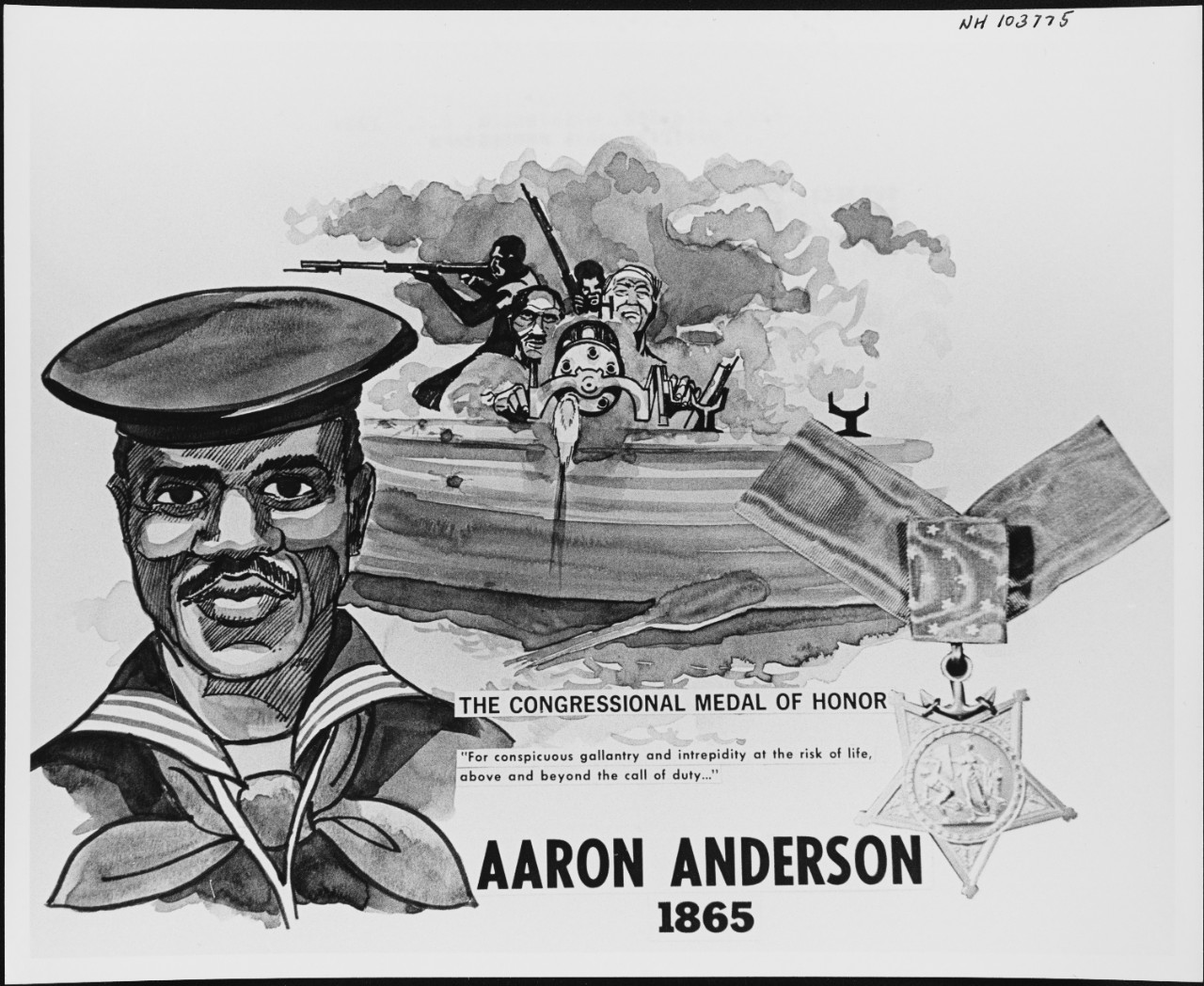

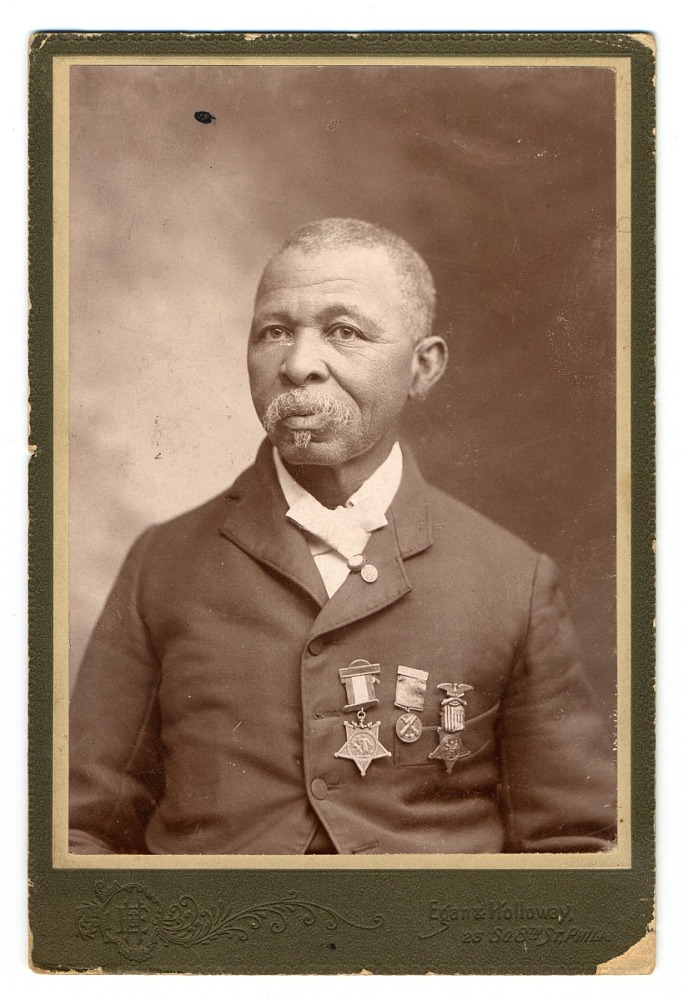

Landsman Aaron Anderson

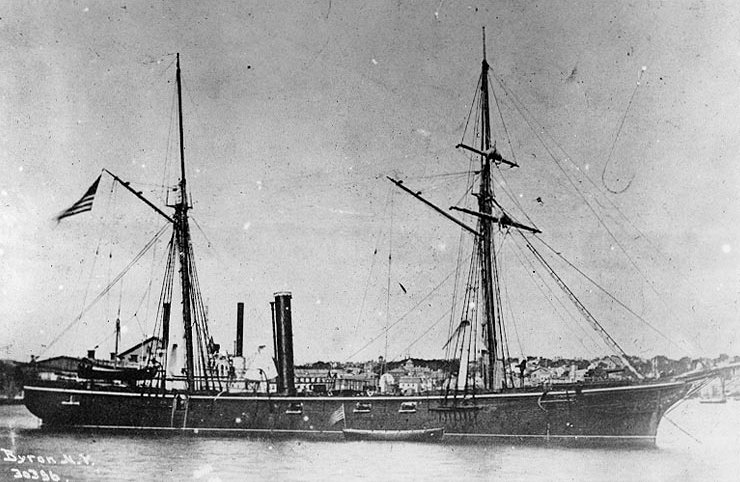

Landsman Anderson served aboard the stores ship USS Wyandank with the Potomac Squadron. Anderson, who is also referred to as Sanderson, received his Medal of Honor for a small boat action on Mattox Creek, Virginia. Wyandank was a sidewheeler built in 1847 and was armed with one 20-pounder rifle and one 12-pounder smoothbore. While on blockading duty on the Potomac River on March 17, 1865, a cutter with one boat howitzer was launched from the USS Don. Ensign Summers commanded the boat, and Anderson was detailed to be among several men rowing the vessel. While clearing the creek’s left branch, the cutter came under heavy fire from about 400 Confederates. The launch continued to move forward to burn three schooners successfully.

When the Union launch endeavored to leave the creek, Anderson “carried out his duties courageously in the face of a devastating fire which cut away half the oars pierced the launch in many places and cut the barrel off a musket being fired at the enemy.” The award citation notes that Anderson rowed while others bailed the boat. The Confederates were chased off by fire from the boat howitzer manned by Boatswain’s Mate Patrick Mullen. Both Mullen and Anderson were awarded a Medal of Honor for their devoted service that day.

Anderson was born in Rogers, Arkansas, and lived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, when he enlisted, at age 52, on April 17, 1863. He left the Navy after his enlistment expired and died on January 9, 1886.

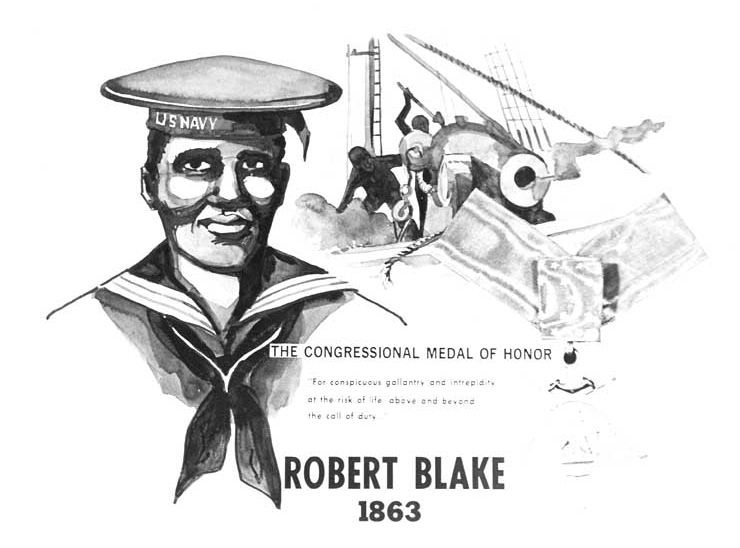

Ordinary Seaman Robert Blake

Robert Blake was born enslaved in Virginia and was later sold to a plantation in South Carolina. He became a contraband when Union naval forces moved up South Carolina’s Santee River. Blake enlisted and was detailed to the ship of the line USS Vermont. Construction of Vermont began at the Charlestown Navy Yard in September 1818; however, the vessel was not launched until September 15, 1848. The ship was not commissioned until January 30, 1862, and was detailed to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron as a store, hospital, and receiving vessel. Blake was reassigned to the Unadilla-class gunboat USS Marblehead, a screw steamer armed with one XI-inch Dahlgren, two 24-pounder smoothbores, and two 24-pounder rifles. A small flotilla of the gunboats USS Pawnee and Marblehead was sent to support Union soldiers laying obstructions to protect their position on James Island in the Stono River above Legareville, South Carolina.

Confederate batteries opened fire on the gunboats. Robert Blake was then serving as steward to the captain of Marblehead, Lieutenant Commander Richard Worsam Mead. When the Confederates opened fire, Mead jumped out of his bed and rushed to the quarter deck to organize the ship’s defense. Blake followed him with his commander’s uniform, dressed him, and was soon knocked down by the explosion of a Confederate shell. Blake replaced the dead powder monkey and kept one of the rifled guns supplied with ammunition. Mead noticed him and asked him what he was doing. Blake replied, “Went down to the rocks to hide my face, but the rocks said there is no hiding here. So here I am, Sir.” [1]

Mead nominated Blake for a Medal of Honor with the citation partially reading: “Serving the rifled gun, Blake, an escaped slave, carried out his duties bravely throughout the engagement which resulted in the enemy’s abandonment of positions, leaving a caisson and one gun behind.” Blake was promoted to ordinary seaman and served another enlistment in the US Navy. There is no further record of his life.

Landsman William H. Brown

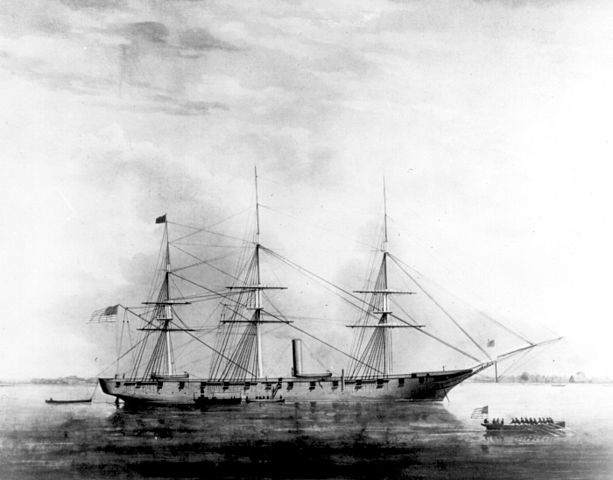

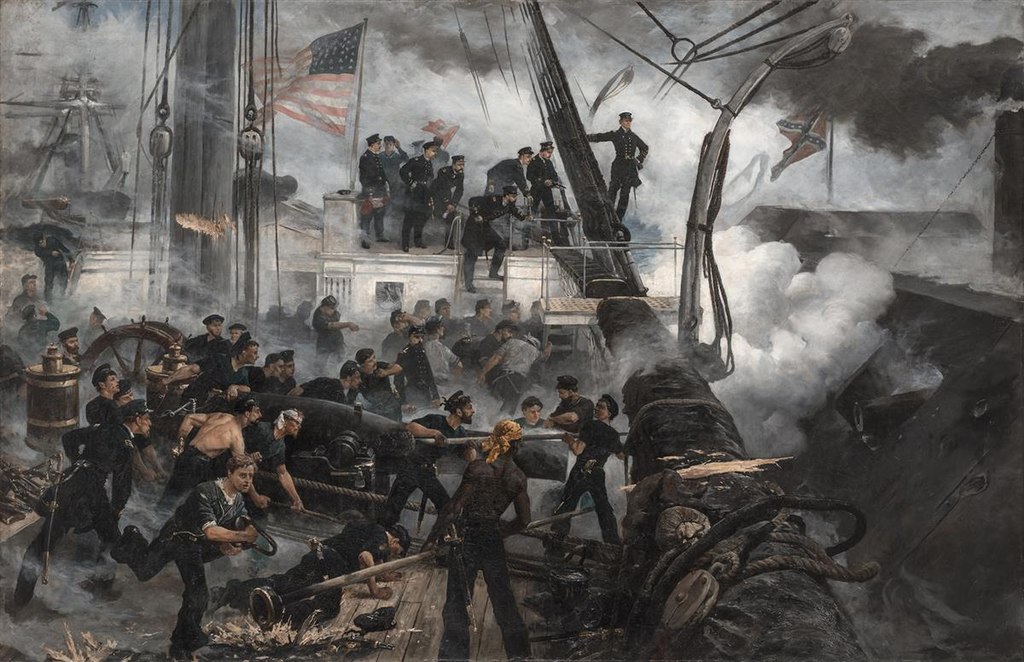

William Brown was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1836 and joined the US Navy on March 23, 1862. The landsman was assigned to USS Brooklyn in the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. The Brooklyn was a steam screw sloop of war armed with twenty IX-inch Dahlgrens and one X-inch pivot shell gun. The sloop, commanded by Captain James Alden Jr., was the lead vessel in the second column of wooden warships attempting to pass Fort Morgan at the entrance to Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864.

When the monitor USS Tecumseh struck a torpedo and sank within 90 seconds, Alden stopped his sloop and began to back away from the torpedo buoys under Brooklyn’s bow. The entire line was momentarily stopped under heavy fire from the Confederate fort prompting the fleet’s commander, Rear Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, to shout, “Damn the torpedoes,” He then ordered full speed ahead as his ship, USS Hartford, swung around Brooklyn and steamed through the torpedo field without incident.

The Brooklyn incurred 54 casualties, and Brown, according to his Medal of Honor citation, “Stationed in the immediate vicinity of the shellwhips [a device for moving shells from the berth deck to the gun deck] which were twice cleared of men by bursting shells, Brown remained steadfast at his post and performed his duties in the powder division throughout the furious action which resulted in the surrender of the prize rebel ram TENNESSEE and in damaging and destruction of batteries at Fort Morgan.” A total of 23 men received the Medal of Honor for their heroic service on August 5, 1862.

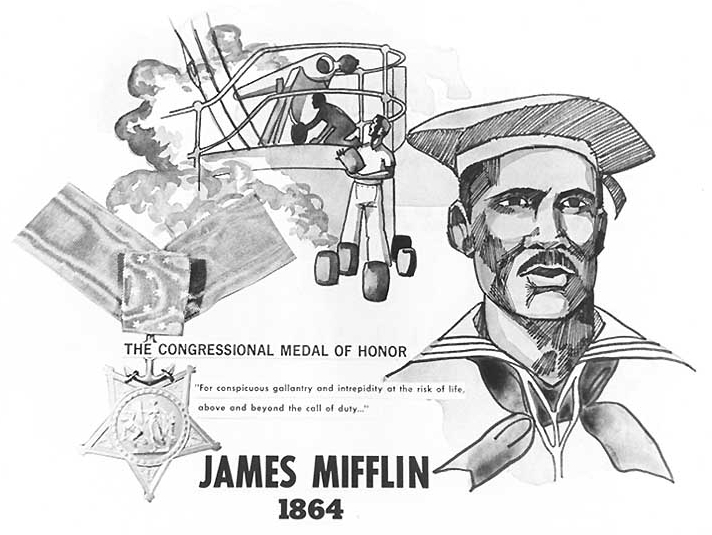

Engineer’s Cook James Mifflin

Another African American sailor aboard Brooklyn was James Mifflin. He enlisted in the US Navy in April 1864 and was assigned to the steam screw sloop. During the Battle of Mobile Bay, he was detailed to ammunition supply duties. His Medal of Honor citation reads precisely like that of Landsman William H. Brown’s quoted above.

Landsman Wilson Brown

Wilson Brown was born enslaved on Botany Bay Plantation near Natchez, Mississippi, in 1841. He enlisted in the US Navy in March 1863, detailed to Rear Admiral David Glasgow Farragut’s flagship USS Hartford. Brown was assigned to help operate a shellwhip during the August 5, 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay. As Brown worked sending gunpowder boxes up to the gun deck, a Confederate shell exploded amongst him and five other men.

Brown’s citation explains why he was awarded the Medal of Honor: “Knocked unconscious into the hold of the ship when an enemy shellburst fatally wounded a man in the ladder above, Brown, upon regaining consciousness, promptly returned to the shellwhip on the berth deck and zealously continued to perform his duties although 4 of the 6 men at this station had been either killed or wounded by the enemy’s terrific fire.” Wilson Brown returned to Natchez after the war living there until he died in 1900.

Landsman John Lawson

John Lawson was a free Black born in Philadelphia. He enlisted in the US Navy in December 1863. Detailed to USS Hartford, he served in the berth deck ammunition section with Landsman Wilson Brown during the Battle of Mobile Bay. Lawson’s citation reads: “On board the flagship USS HARTFORD during the successful attacks against Fort Morgan, rebel gunboats and the ram TENNESSEE in Mobile Bay on 5 August 1864. Wounded in the leg and thrown violently against the side of the ship when an enemy shell whipped on the berth deck, Lawson, upon regaining his composure, promptly returned to his station and, although urged to go below for treatment, steadfastly continued his duties throughout the remainder of the action.”

John Lawson left the Navy in 1865 and worked as a ‘huckster’ (peddler of small trinkets) in Philadelphia until he died in 1919.

Signal Quartermaster Thomas English

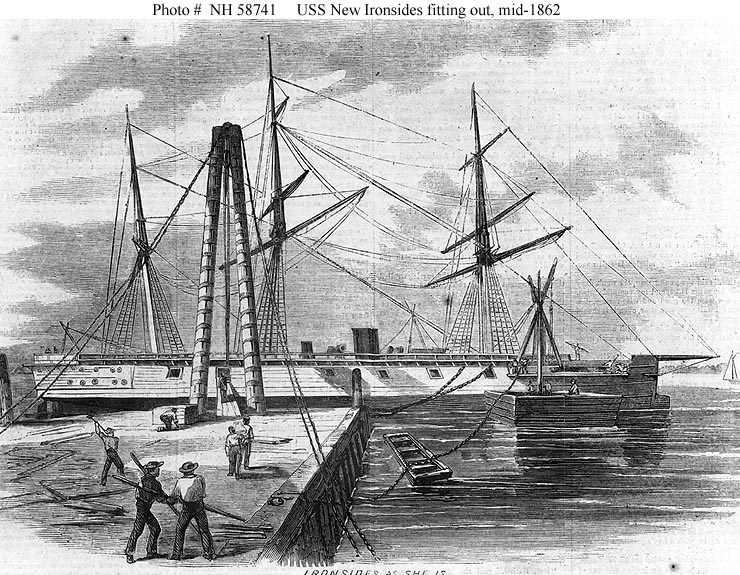

Thomas English, a free African American, joined the US Navy in 1862 and was detailed to the USS New Ironsides, commanded by Thomas Turner. This warship was a broadside ironclad based on the design of the French ironclad La Gloire. The New Ironsides had an iron belt of 4.5 inches and was heavily armed with fourteen XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns, two 150-pounder Parrott rifles, and two 50-pounder Dahlgren rifles.

English was part of a crew of 449 officers and men. Signal Quartermaster English is considered the highest-ranking Black sailor during the Civil War. He fought during DuPont’s ironclad attack against Charleston and in the First and Second Battles of Fort Fisher. During the Fort Fisher attacks, his heroic actions caused him to repeatedly and with composure leave the safety of the armored pilothouse to change the signal flags vital to communications during a storm of shot and shell. As a result of his heroic and daring actions, he was awarded the Medal of Honor on June 22, 1865.

After the war, English remained in the Navy and was eventually detailed to the steam screw sloop USS Piscataqua. The sloop was assigned as the flagship of the Asiatic Station. English died onboard off of Singapore and was buried at sea.

Ordinary Seaman Joachim Pease

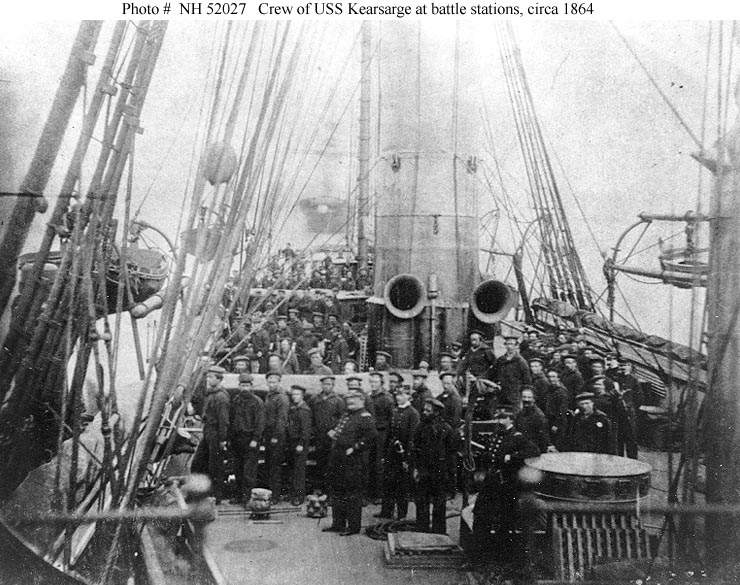

Joachim Pease was a native of Fogo Island, Cape Verde Islands. His family later moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts. He enlisted in the US Navy on January 12, 1862, and was detailed to the Mohican-class sloop of war USS Kearsarge. When this Union ship sank the CSS Alabama off Cherbourg, France, Pease was aboard on June 19, 1864. It was said of Pease that during the engagement, that he, “Acting as loader on No.2 gun during this bitter engagement. Pease exhibited marked coolness and good conduct and was highly recommended…for gallantry under fire.”

Why These African Americans Fought So Heroically

Many African American sailors served with distinction throughout the war, continuously demonstrating their skill and bravery during numerous engagements. During the March 8-9, 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads, 16 African Americans made up the entire crew of USS Minnesota’s aft pivot gun. The Minnesota’s commander, Captain Gershon Jacques Henry Van Brunt, praised this gun crew: “The Negroes fought energetically and bravery-none more so. They evidently felt that they were thus working out the deliverance of their race.”[2]

Footnotes

1.Charles H, Hanna, African American Recipients Of The Medal Of Honor: A Biographical Dictionary, Civil War To Vietnam War, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002, pp. 17-19.

2. Official Records Of The Union AndConfederate Navies In The War Of The Rebellion, Ser. I, Vol. 7, pp.12-13.