While the most recognizable way for individuals to serve their country at times of war is through the service branches, there have historically been many other ways in which people served their country abroad and at home. For example, the United Service Organizations, better known as USO, a nonprofit-charitable organization which provides leisure facilities and shows to United States Armed Forces was founded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in 1941, to “unite several service associations into one organization to lift the morale of [the] military and nourish support on the home front” (USO.com/about).

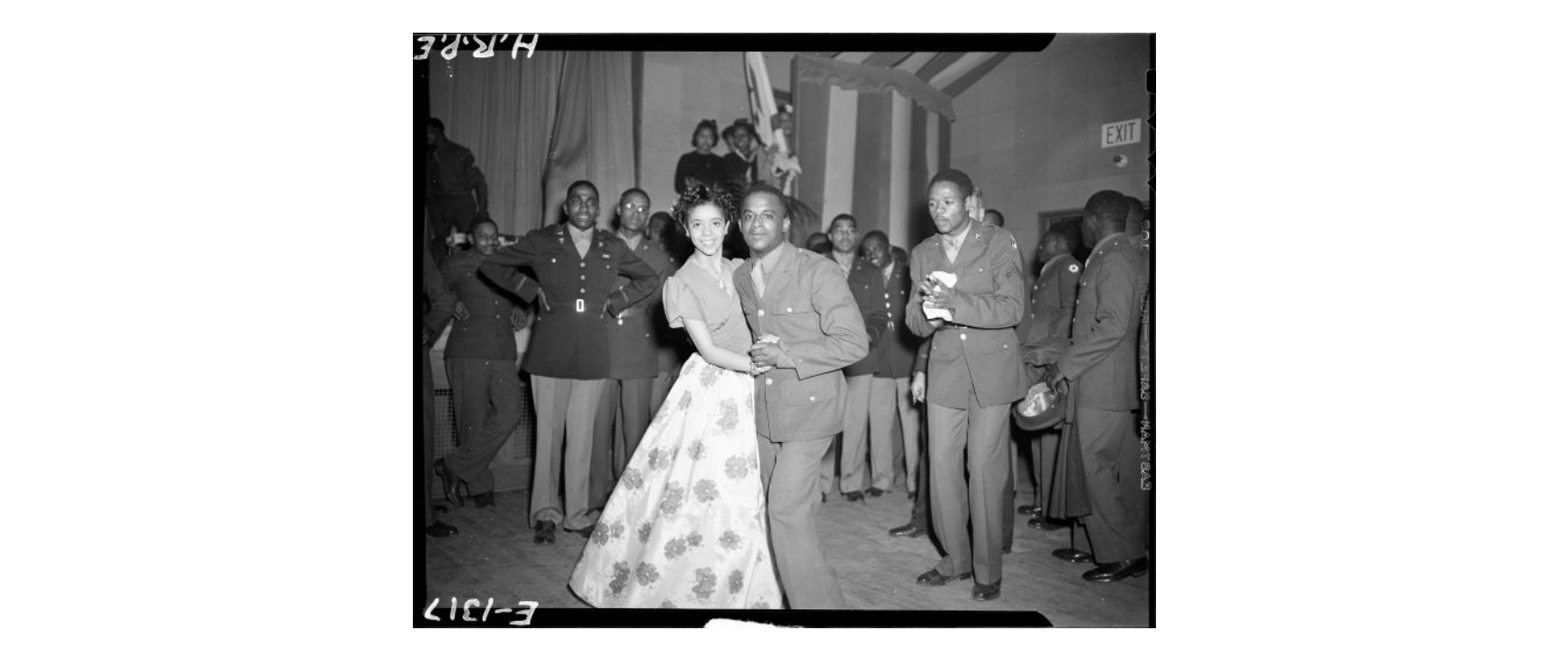

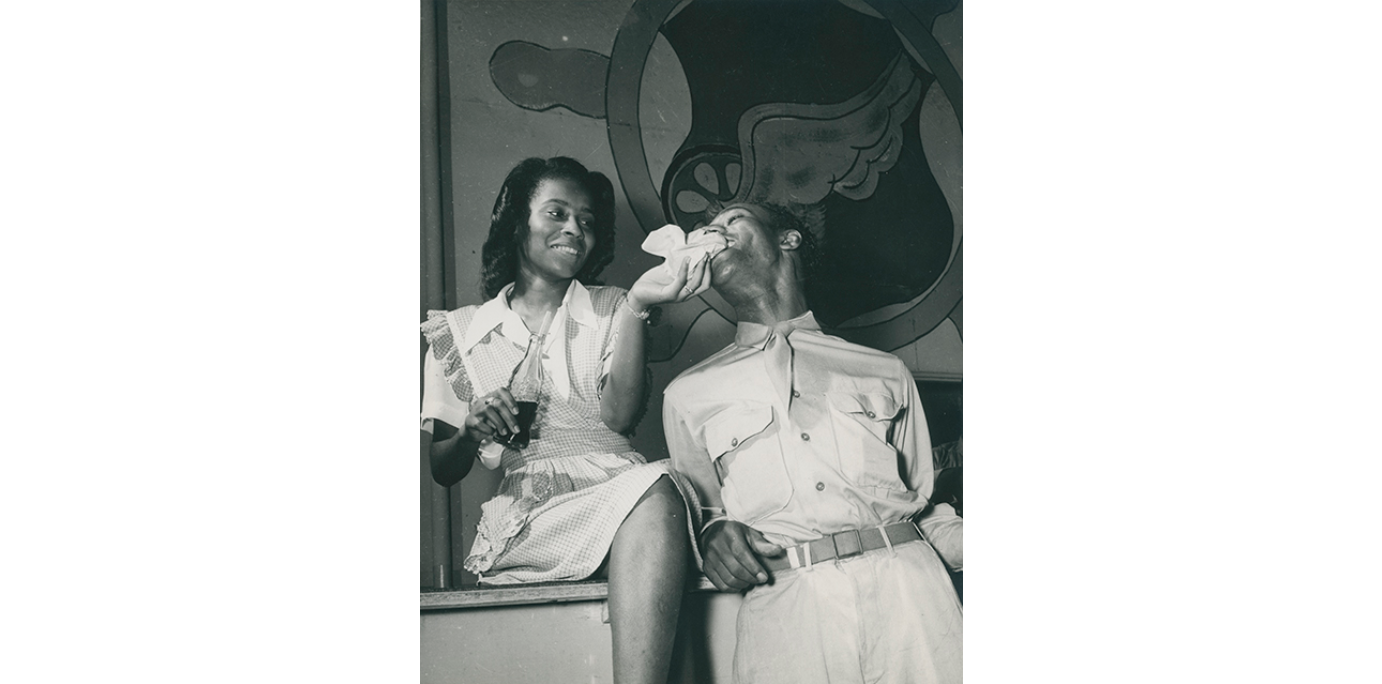

In fact, during World War II, there were estimated to be about 3,000 USO clubs worldwide, and Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation was no exception. USO clubs helped soldiers feel at home and gave them the opportunity to step away from the job and the realities of war. They provided leisure, like dances, ping pong tables, and other games; entertainment, sometimes local bands or even Hollywood celebrities would make an appearance (!); and they often had a snack bar, too, selling sandwiches, smokes and soda (but not liquor!) to service people.

During WWII the US military was, unfortunately, still a segregated institution. This included not only the US service branches, but their various volunteer and women’s groups (some of which we’ve already written about) like the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), Army Nurse Corps (ANC), Women’s Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service (WAVES), and Semper Paratus Always Read (SPARS); USO clubs were no exception. Many Black, Indigenous, and People of Color served and supported the war effort despite these discriminatory regulations, though. But that did not mean their work was not hard, or in many cases even unsupported. This also meant that African American service-people and civilians had to work to open an African American USO Club at HRPE.

“African American women found themselves not only providing all unpaid labor for the USO Colored Division staff but also finding money to provide facilities for the soldiers. However frustrating it was, helping with the USO provided a real center of power by enabling black women to provide important infrastructure for housing and entertaining millions of troops. Because the USO and Red Cross considered black troop morale an after thought in their recreation programs, women raised money to start troop centers in their own cities” (Shockley, 42-43).

USO clubs also provided a valuable way for women to help the war effort. They were often run and coordinated by civilian women local to the area, in the roles of Senior or Junior Hostesses. Senior Hostesses were married women over 35, usually with some standing in the local community. They organized and coordinated social events and dances, as well as the food supply for the snack bar. All in all they made sure every event ran smoothly and served as the backbone of USO Clubs. Senior Hostesses also served as chaperones for Junior Hostesses.

Junior Hostesses were single young women who volunteered to entertain soldiers and host social events. They were chosen under very stringent qualifications. A Detroit reporter wrote “We learned in our visit to the servicemen’s center that the young women known as junior hostesses are only selected after careful and painstaking appraisal … they undergo a training which consists of lectures on personality, appearance, topics to be discussed and those to be avoided…” (Shockley, 43). They had to follow a strict set of rules as a part of the USO. Junior Hostesses were not allowed to date servicemen that they met at USO clubs, and they were not allowed to drink on the job. They were also required to take a yearly class on charm, etiquette, and the duties of USO Hostesses.

A Junior Hostess also had a bit of a uniform to follow-no slacks allowed! In the image below, you can see the Junior Hostess to the right is in a USO Hostess Uniform, styled after women’s military uniforms of the time. Wearing the uniform was not a requirement; however, as shown below by Hostesses to the left, who are dressed in their nicest “civilian clothes”.

All of these rules were vital in protecting these young women and retaining the respectability of the USO program. Even while recognizing that these women provided a significant morale boost, “there was no getting around the fact that having eighteen- to twenty year-old unmarried women provide entertainment made tenants of ‘respectability’ questionable” (Shockley, 42). And in a day and age where women were particularly critiqued for their femininity and sexualization (both too much or too little), these trainings, rules, and the chaperone program became integral to the hostess program.

While Senior and Junior Hostesses mainly worked at USO clubs to sell snacks, attend dances, play cards, and help entertain soldiers, they came up with other creative ways to support the war effort, too. At some clubs, Junior Hostesses would set up button sewing or uniform mending stations. At other clubs, hostesses helped soldiers write and organize their letters home. Creativity was also implemented in dance admission by “charging” scraps for scrap drives or collecting cigarettes to send overseas.

Senior and Junior Hostess worked together to help entertain service people and bring some levity to their lives during a serious time. By providing a place of community and joy, USO Hostesses helped keep service-members connected to family, home, and country during service.

At The Mariners’ Museum, we are lucky to have a fair number of HRPE images that show both Black USO personnel and involved service members. This may be in large part because Hampton Roads had several USO Clubs including an African American Service Club. Since Black, Indigenous, and People of Color’s contributions are, frankly, under-represented in our HRPE photo collection, we are excited to share this story illustrated purely by images of these men and women.

To all the USO staff, volunteers, and contributors – thank you.

Biblio:

https://www.uso.org/stories/149-in-the-uso-s-early-years-hostesses-provided-a-wholesome-morale-boost

https://www.uso.org/stories/34-a-different-way-of-serving

https://www.uso.org/stories/460-black-history-month-and-the-uso