A great deal of our collection is related to explorations and discovery, because so many of those took place by way of the oceans and rivers of the world. We have objects related to the big names in exploration and also some who are not as famous. So I was interested a few months ago to hear a news report refer to an explorer I had not heard of: Matthew Henson. I went straight to our database to learn more!

The report I heard discussed the conservation of 20 dioramas built for the American Negro Exposition held in Chicago between July 4 and September 2, 1940. There were originally 33 dioramas but 13 have disappeared. The Legacy Museum at Tuskegee University is using the conservation of the dioramas to help teach Black art students who have preservation experience. This will help build diversity within the conservation field. The dioramas each displayed significant stories in American history that prominently featured Black Americans such as Crispus Attucks, the WWI Harlem Hellfighters, surveyor Benjamin Banneker, and Arctic explorer Matthew Henson.

Matthew Henson’s Early Years

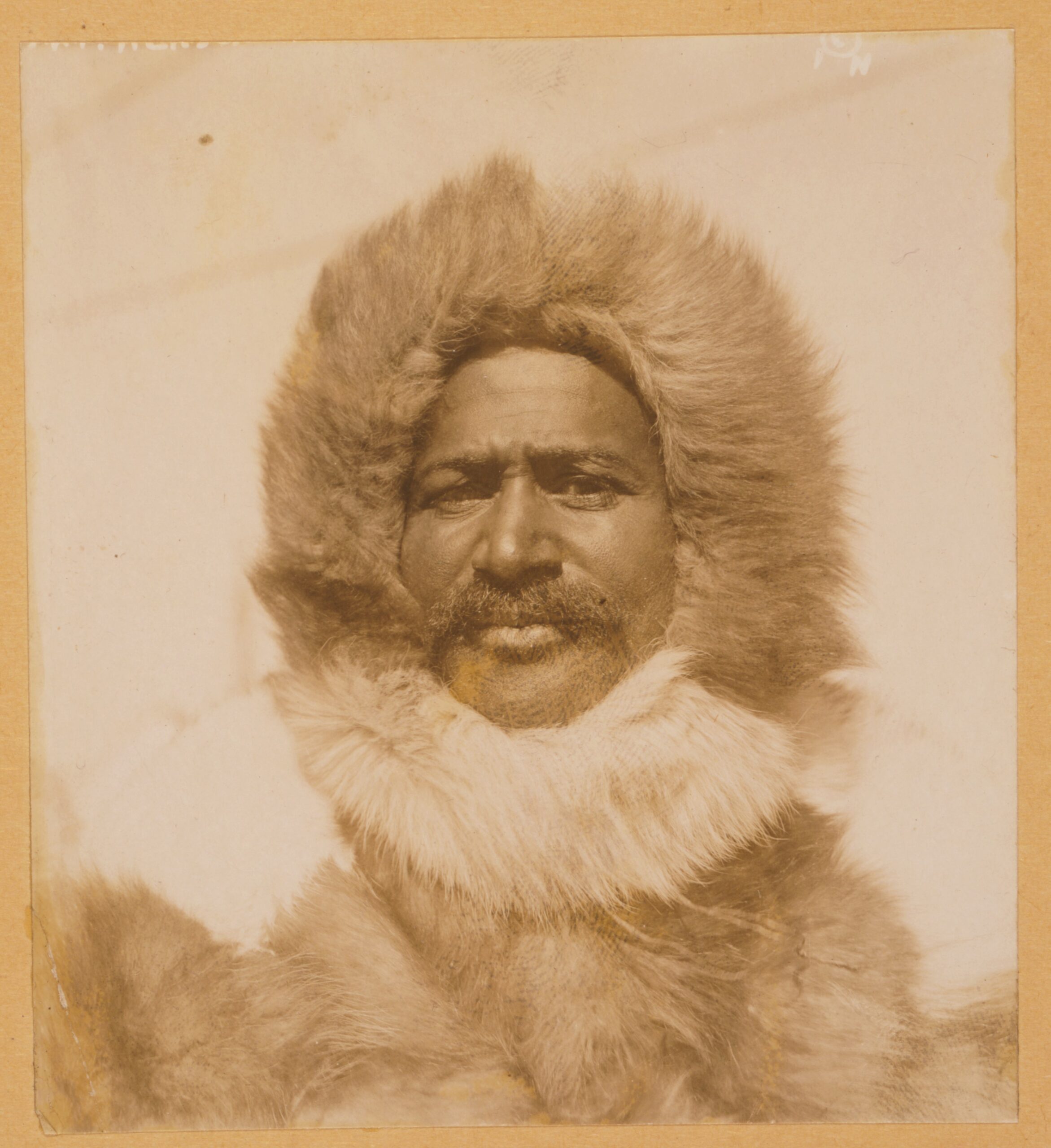

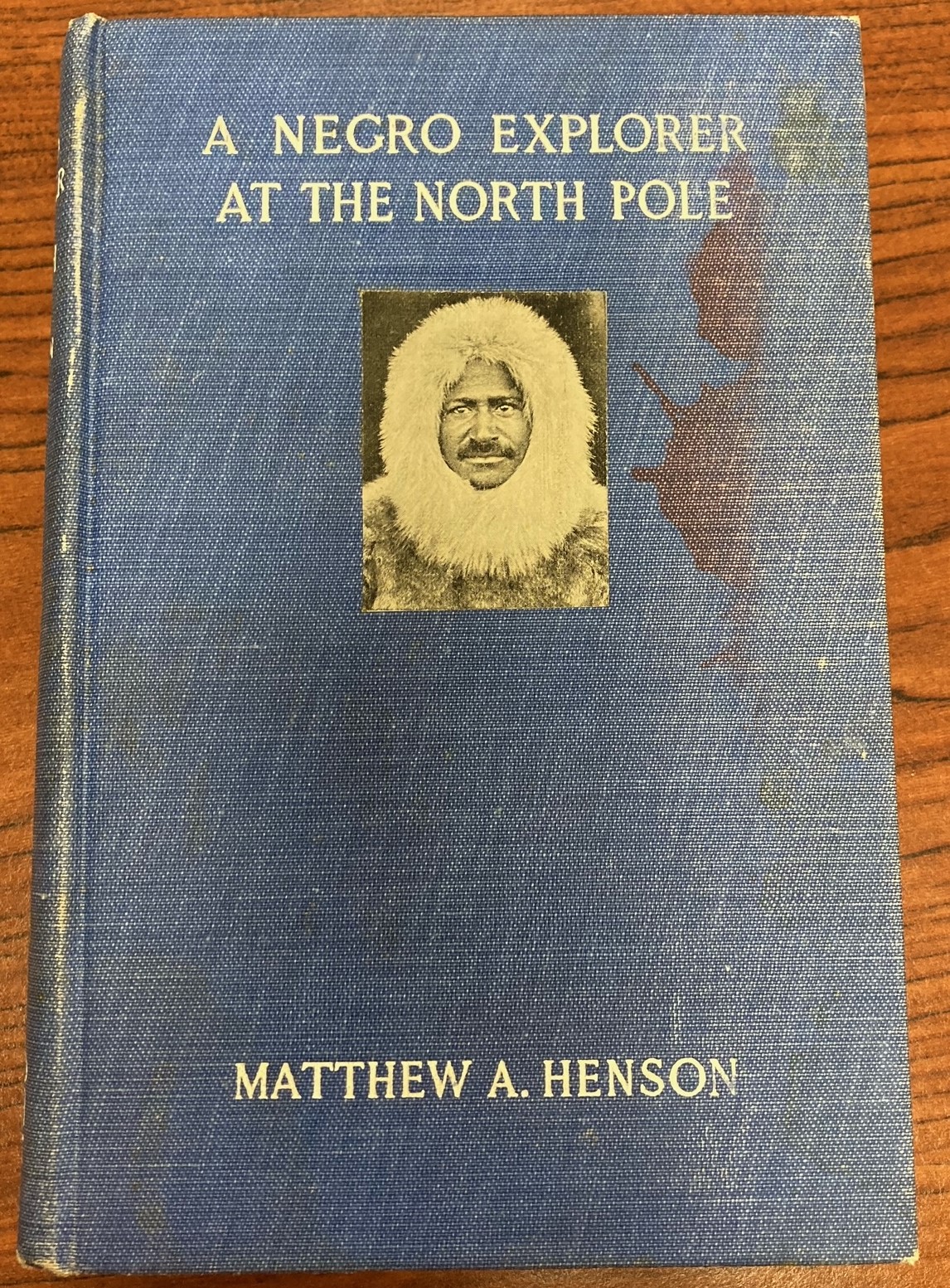

Henson was born in Charles County, Maryland on August 8, 1866, the son of Black sharecroppers who “were both free born before me” as he wrote in his 1912 book, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole. The book gives a first hand account of his life, particularly his years exploring Greenland and the Arctic.

Henson’s parents died while he was young, so after a few years of school he went to sea. Henson quickly worked his way up to an able bodied seaman and traveled the world for four years while learning to sail and navigate. This in turn caught the attention of Robert Peary, who hired Henson as an aid for his surveying expedition to Nicaragua in 1888.

After their tropical trip the two men decided to venture to the opposite climate. Peary had been to the Arctic once and now invited Henson for a return visit in 1891. The two men ended up working together for more than two decades on seven Arctic expeditions.

Way More Than Just an Aid

Henson wrote that his job as an assistant included “a multitude of duties, abilities, and responsibilities.” In reality this meant that Henson was an integral part of the team. Not only could he navigate but he was also a skilled mechanic and carpenter who built the sledges, commanded the dogs, hunted for food, and spoke the local language which allowed him to communicate and trade more efficiently.

After several earlier trips, in 1905 the crew arrived in the Arctic on SS Roosevelt. Peary designed this ship after Fridtjof Nansen’s Fram, with an egg shape that would allow it to rise with the ice rather than get crushed by it. The Library of Congress has a video of Roosevelt at harbor in New York from that year. Peary and Henson almost reached the geographic North Pole then, but didn’t quite make it.

Heading for the North Pole

In 1908 the team set out on Roosevelt again. There is much debate about exactly what happened when they reached the North Pole on April 6, 1909. According to Dr. S. Allen Counter in his book North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo, “Henson maintained that he reached the Pole some forty-five minutes ahead of Peary after inadvertently disobeying the commander’s orders to stop short of what they judged to be the actual spot. There he was to wait so that Peary could travel on alone and lay claim to the honor of being the first person to stand at the North Pole.”

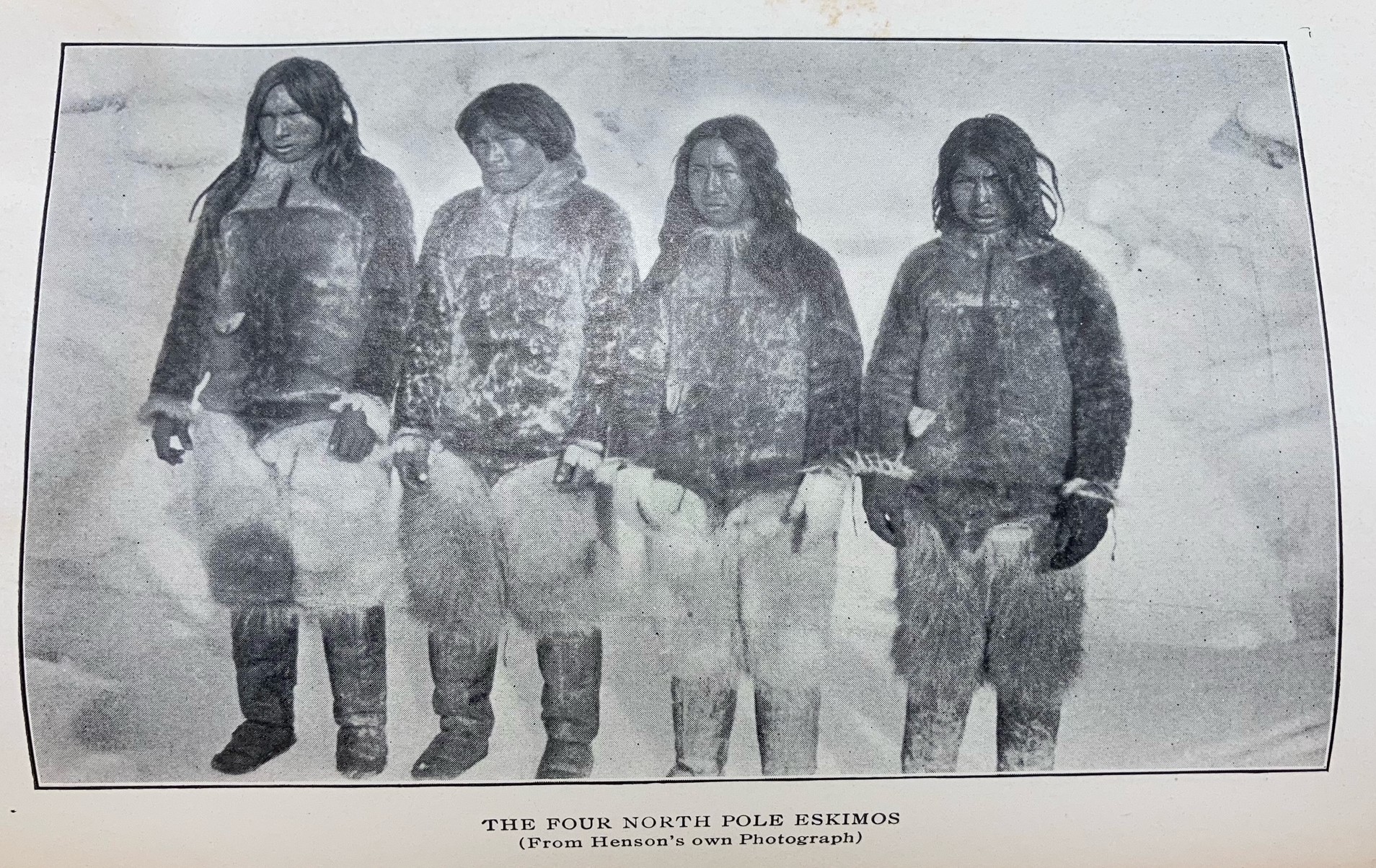

In his book, Dr. Counter describes how Henson may have deliberately pushed ahead knowing that on the return home Peary (who was white) would receive the credit either way. The only people at the North Pole were Peary, Henson, and their four Inuit guides: Ootah, Seegloo, Egingwah, and Ooqueah (or Iggianguaq, Sigluk, Odaq, and Ukkujaaq, in modern spelling). So why not get there first and enjoy that personal accomplishment? After all of his training and the many trips to the Arctic, Henson was just as qualified and in better health than Peary.

Reactions at Home

Newspapers in 1910 published stories where Henson discussed how Peary ignored him the rest of the way home and refused to pay him. On top of that the men had their hands full back in the United States. Peary and Henson discovered that another team led by Frederick Cook had claimed that they were the first to reach the North Pole a year earlier. This meant Peary and Henson had to prove what they did, and Dr. Counter writes that Henson never spoke out against Peary during these arguments. Peary’s expedition eventually received the official certification for being the first and he enjoyed the accolades for the work.

Peary went on to become “the famous explorer Peary,” and Henson received little national recognition. He toured the country thrilling audiences with his Arctic adventures, dressed in his fur parkas. The 1910 federal census lists Henson as a lecturer who worked in the theatre industry. However, the census also says that he had been out of work for five weeks. Peary controlled what Henson said, the photographs he shared, and how often he spoke. He blamed it on the controversy with Cook while they worked to prove who really reached the North Pole first.

In 1912 Henson published his book detailing the adventures. In it he references Peary not speaking to him once they were on board Roosevelt. He makes no mention of getting to the Pole first, probably because Peary reviewed the manuscript and wrote the forward.

The following year, 1913, President Howard Taft appointed Henson “to any suitable position in the classified service.” He began as a messenger at the U.S. Customs House in New York City, and over the next 23 years worked his way to being a chief clerk. He retired in 1936 after the position was eliminated.

Finally Earning Some National Recognition

It was in the later years of Henson’s life (most after retirement) that some measure of fame came his way. The Explorers Club made him an honorary member, the Navy and Chicago Geographical Society awarded him medals, and both Morgan State College and Howard University awarded him honorary master’s degrees. In 1954 Henson and his wife, Lucy, went to the White House to meet President Eisenhower.

Matthew Henson died the next year, on March 9, 1955. In the 1980s Dr. Counter began researching Henson and came across stories of possible family members in Greenland. He traveled there in 1986 and was able to meet with Henson’s only child. A woman named Akatingwah had given birth to his son, Anaukaq, on Roosevelt in 1906, during Henson’s second to last visit to the Arctic and between his two marriages.

After meeting the family Dr. Counter was able to convince the federal government that Henson should be buried in Arlington National Cemetery. On April 6, 1988, the 79th anniversary of reaching the North Pole, Matthew and Lucy Henson were reinterred with his family in attendance. Anaukaq had passed away by then, but his children and their families were able to be part of the ceremony.

As with most expeditions of discovery, the contact with the local communities rarely benefits the indigenous people. Peary’s Arctic explorations were no different. But Matthew Henson was the only person on the team who took the time to learn the language and culture. This allowed the Americans to live off the ice and have a better chance of survival with the help of the Inuit communities. This knowledge, combined with two decades of experience, made Matthew Henson a critical team member in the quest to reach the North Pole.