Love of Science

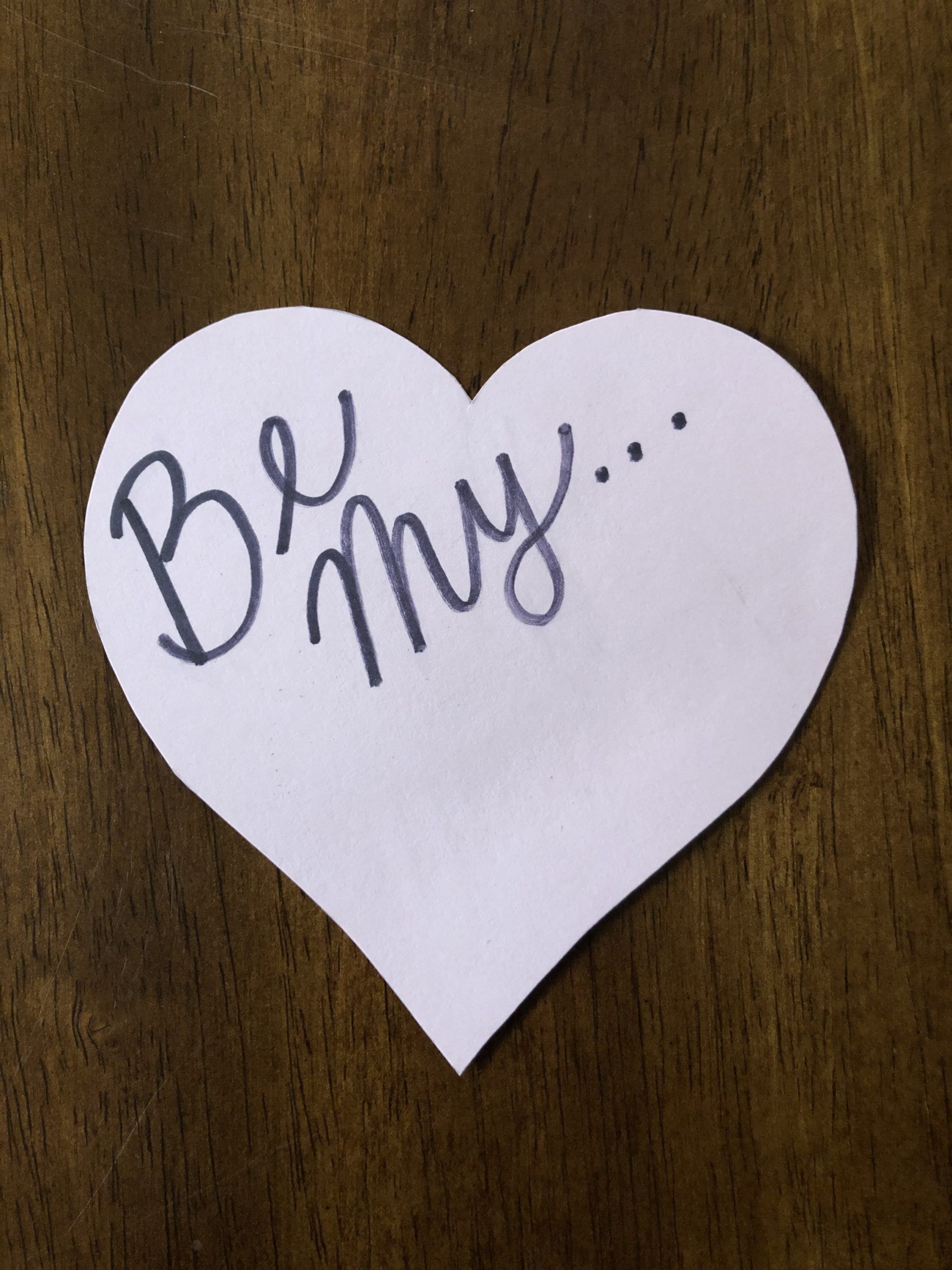

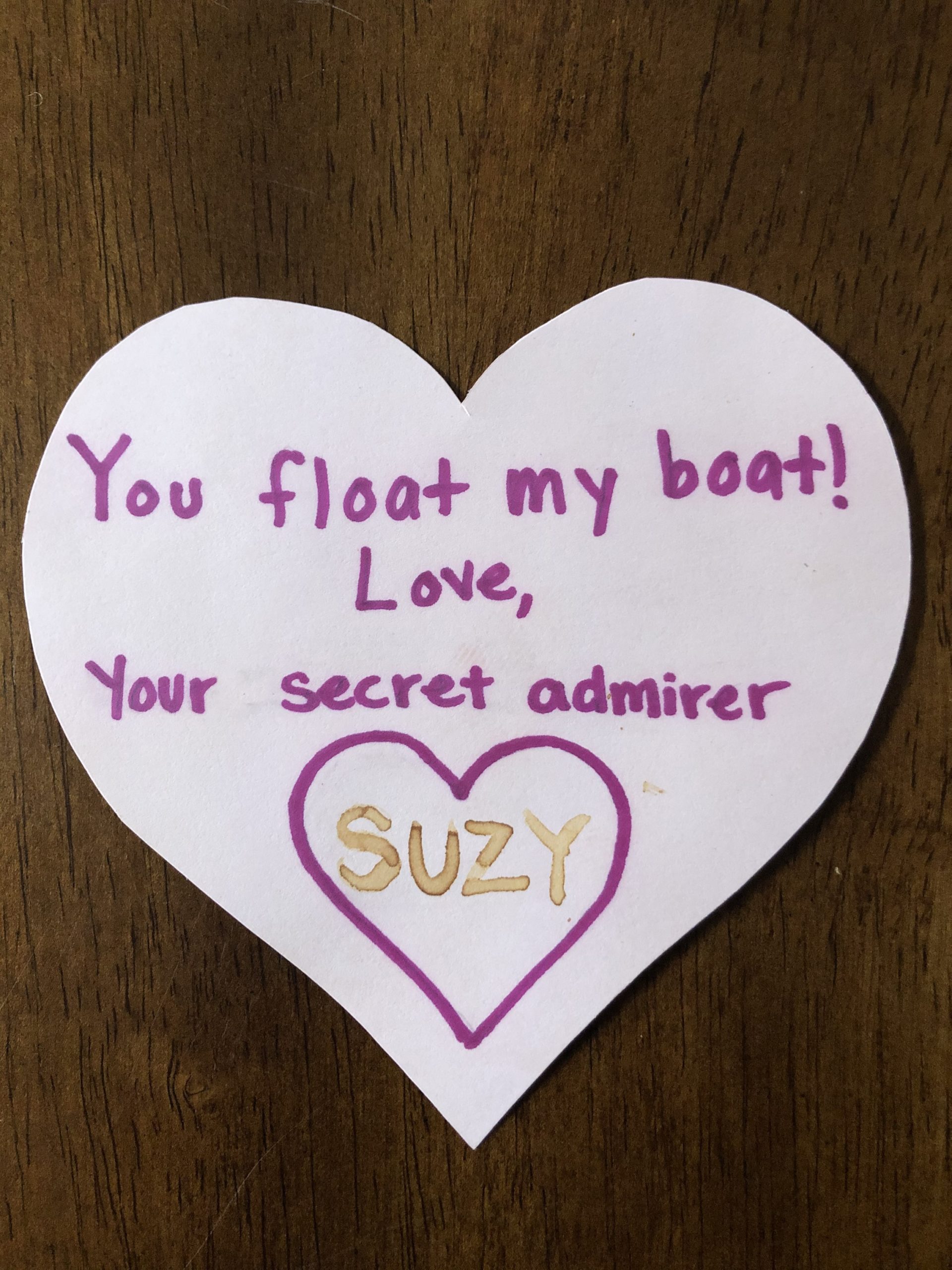

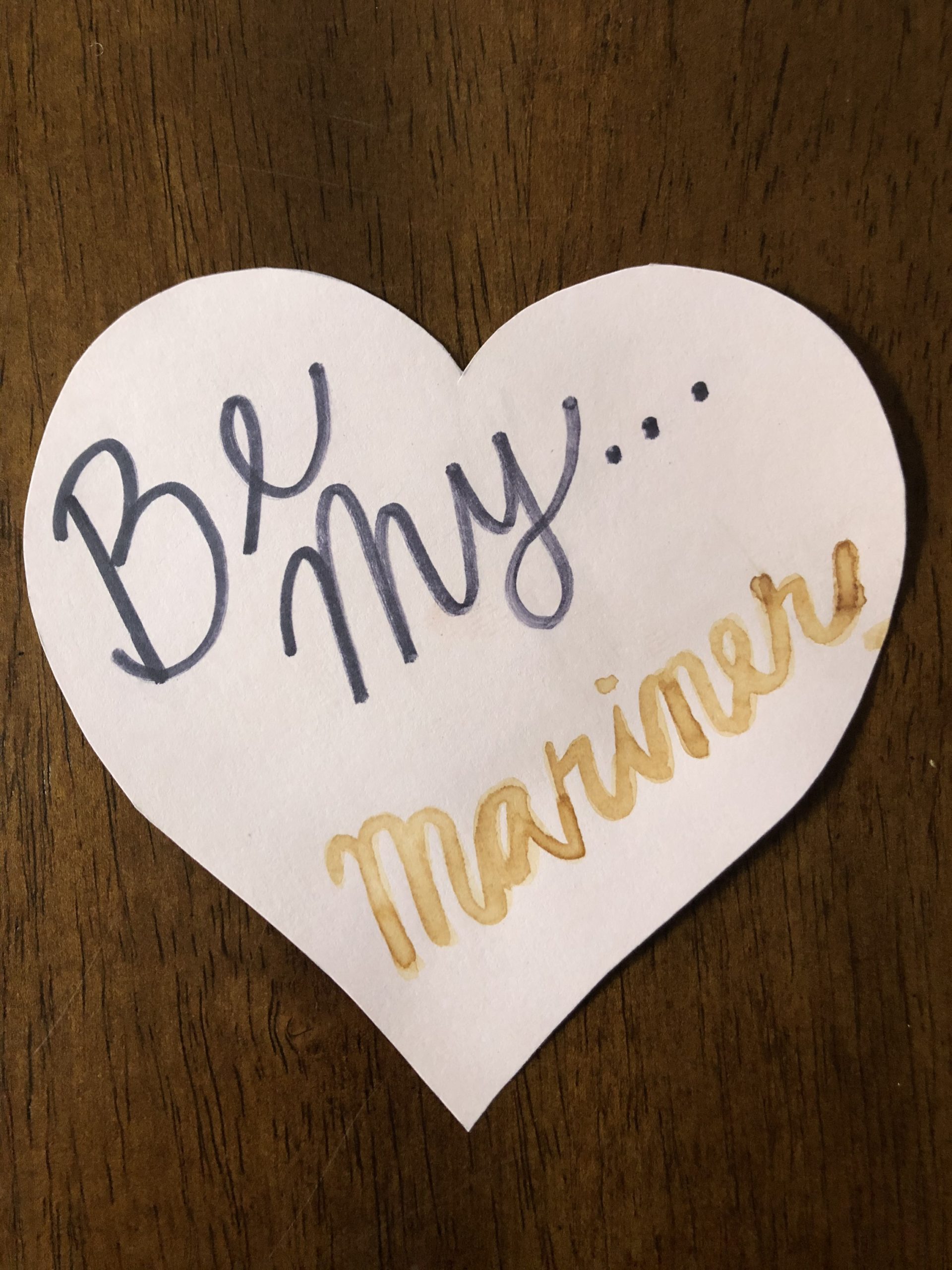

A few years ago, we began to combine our science and your art to help make secret valentines for your favorite mariners. We used our Infrared Camera to show off messages that were hidden in Valentine’s Day cards made by visitors to the museum and taken home to share with their loved one(s). While we can’t meet in person this year to do this activity, we can assist in making some secret messages for that special someone on Valentine’s Day! This year we are going to explore the making and use of, drumroll please, Invisible Ink!!!!

Invisible Ink

To give a little background there are a number of different formulations of invisible inks to choose from (for more on other invisible inks check out The Secret History of Invisible Ink). We decided to choose a formula that most people should have easy access to in their kitchen: acid based invisible ink. Perhaps the most commonly known invisible ink is lemon juice, which is a highly acidic juice from a nice smelling fruit. Never fear! If you don’t have lemons, or lemon juice, there are other options for making invisible ink.

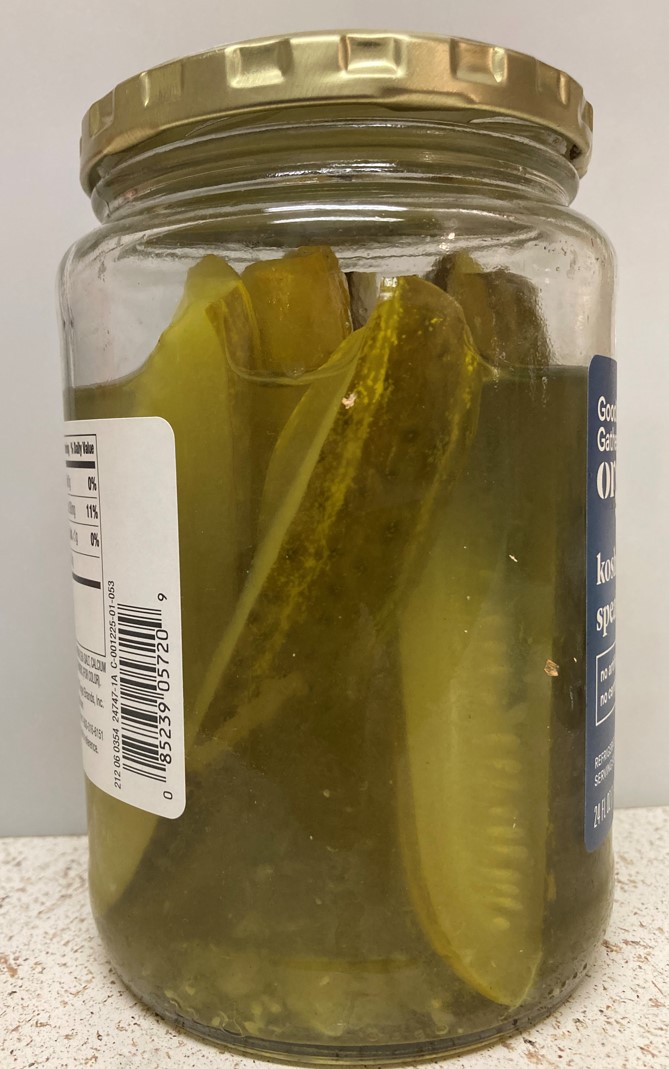

Most citrus fruits will work, as the sour taste indicates an acid. (Some citrus fruits may have enough color in their juice to leave behind some color on white paper. Keep this in mind before you use them). Also, vinegar is a good option as well. If you don’t have standard vinegar you may look to your pickle jar too! Differences in the concentration of acid in these compounds make a difference in how well the ink will show when developed. It is worth trying out your acid-based ink prior to making your final secret message(s) for your favorite Mariner(s)!

Science of Paper & How This Invisible Ink Works

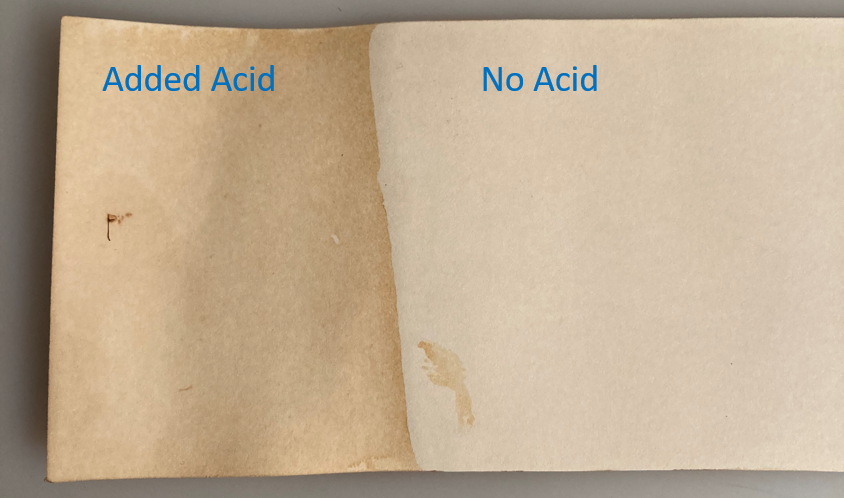

Invisible inks based on acids like lemon juice or vinegar actually take advantage of the chemistry of paper and the fact that it breaks down in the presence of acid. This reaction is fairly slow at room temperature, but over time the acidic breakdown of paper is what causes paper to yellow as it ages.

This aging of paper also causes “book smell” at least some of the “book smell” that we are familiar with. (While trying out different oven temperatures I (Molly) began to smell a hint of vanilla coming from my kitchen. Vanillin, the main flavoring chemical in vanilla, is a byproduct of the wood pulp aka paper industry. So it makes sense that heating up some copy paper in my oven gave me a fairly nice smell!).

Back to the chemistry:

Heating up the paper speeds up the reaction of the acid with the paper. The addition of acid in a concentrated area of the paper (writing) means that this area of the paper breaks down more quickly and thus changes color more quickly.

If you happen to have an acid mixed in with a bit of sugar (see most citrus fruit juices sold as juice) you also get the benefit of the sugar in the mix that browns along with the paper. A bit of caramelization of your ink, if you will.

When We Don’t Love Acids in Paper

Here we are harnessing the effects of acids in paper for good, but in most cases paper and acid are not so sweet on each other!

Not only does acid turn the paper brown as it breaks it down, it also makes the paper very brittle and delicate so that it breaks easily when bent.

External Acids

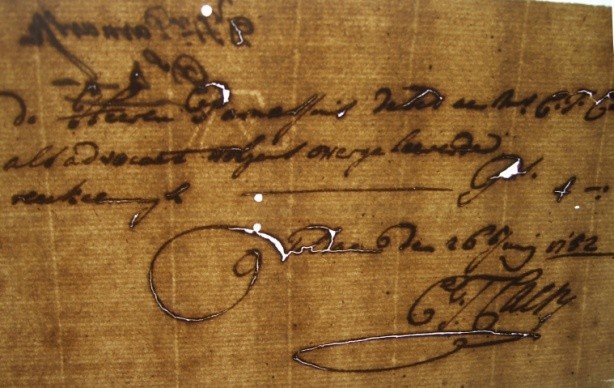

Where does acid come from in paper? It depends! It can be added to the paper from other materials that touch it, like our “ink”. For example, iron gall ink, which was widely used for centuries, can be very acidic, and in extreme cases can cause areas of the paper to fall out! (A different kind of “invisible ink?”)

Internal Acids

Acids can also come from the paper itself, depending on what it is made from. Most people know that paper comes from trees, meaning wood. But this was not always the case! Early paper was made from cotton and linen cloth rags. These types of fibers tend not to break down as much over time, so the paper made from them can stay flexible and bright for hundreds of years!

This practice changed when the papermaking machine was invented in the early 1800s. The new machines made paper so fast that they literally ran out of rags to use! Instead, the papermakers started using wood pulp, which naturally has higher acid content (also there were some chemical processes used to break up the wood pulp that contribute to the acid content as well). As a result, the period between 1850-1950 is referred to as the “brittle books era” since much of the paper made then has degraded rapidly. Today, wood pulp is chemically treated before use, so the acidic parts are either removed or neutralized, resulting in longer-lasting paper. (To learn more about paper-making see: https://www.marinersmuseum.org/2020/05/paper-and-water-friends-or-foes/)

Top: The left image shows workers sorting through rags for use in papermaking, and the right image shows paper being made, one sheet at a time, from those rags. (Diderot Encylopedie, Paris: 1751-1765.) Bottom: Image of one section of a more modern Fourdrinier paper-making machine (c. 1950). Imagine how much more paper this machine can make than the single papermaker above!

The Good News

Whether the acids come from inside or outside the paper, the chemical reactions by which they break down the paper can be sped up by other factors like light, humidity, and – as we see from our invisible inks – heat! That’s why it is important to keep paper in dark, drier (humidity at ~50% RH) – aka NOT your attic! Museums have specially controlled environments for artifact storage which extends the life of paper (and other materials) by keeping these reactions at bay.

Image Credit: The Mariners’ Museum and Park

But what if the damage has already been done? Paper conservators have a couple of tricks up their sleeves when it comes to acidic paper. Sometimes, water can be used to wash out acids that have built up in the paper over time. (This is also true of your invisible ink, if you get the paper wet after you write your message, your message will wash away!) Another option is to add basic, or alkaline, chemicals to the paper to neutralize the acids and prevent them from breaking down the paper.

The Bad News

Unfortunately, many papers and books made with acidic wood pulp have suffered irreversible damage, and since the paper itself is inherently acidic the degradation cannot be stopped and the condition of the paper will become worse and worse over time. In these cases, reformatting (usually via digital photography) is the best form of preservation, ensuring that future generations will have some form of access to the artifacts.

We will undoubtedly talk more about digital preservation in future blogs, but if you are interested in learning more about the topic generally check out the Library of Congress’s resource page: https://www.digitalpreservation.gov/.

Recipe for Making Your Valentine

Materials

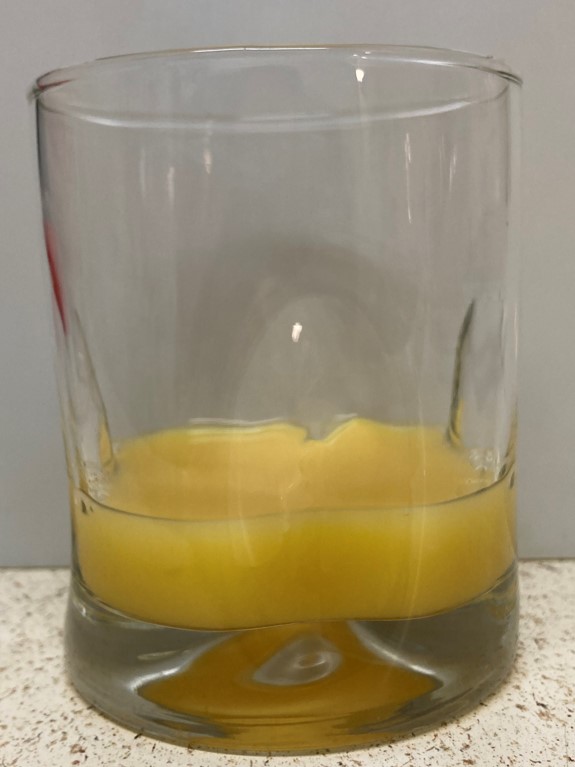

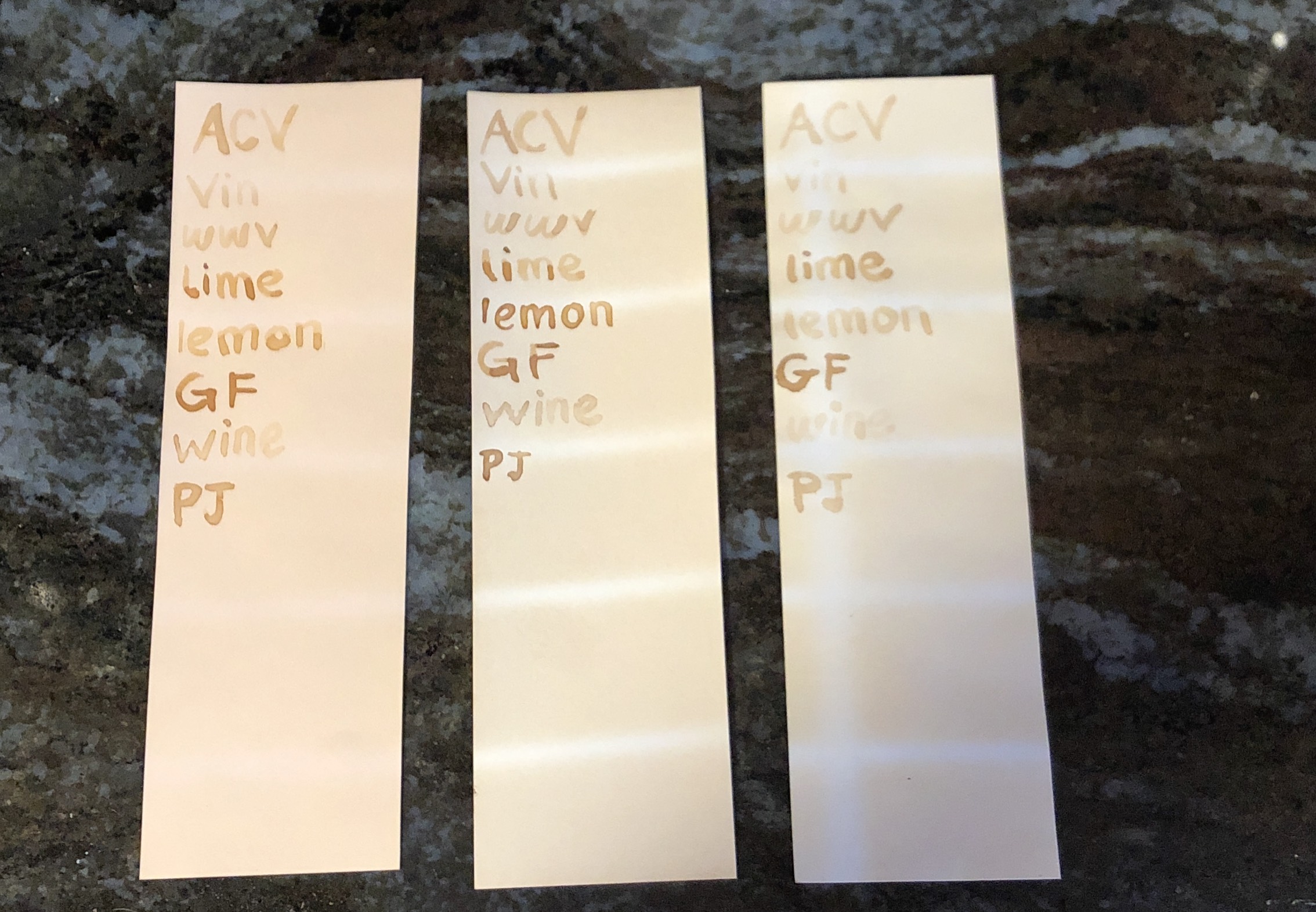

- Ink – Lemon juice (or other acid source – vinegar, fresh squeezed citrus juice. Check out the image below for options you might have in your kitchen.)

- Paper – white, or lightly colored paper. (Feel free to try colored construction or cardstock paper, it may be harder to read.)

- Writing/drawing instrument (a paintbrush works well, but feel free to experiment!)

- Heat source – oven at 400 F for two minutes (minimum) or a lit candle with adult supervision

Three papers – left pink cardstock, middle white cardstock, right white printer paper.

ACV – apple cider vinegar, vin – vinegar, wwv – white wine vinegar, lime – lime juice, lemon – lemon juice, GF – grapefruit juice (with sugar added), wine – white wine, PJ – dill pickle juice

Image Credit: The Mariners’ Museum and Park

Directions

- Using your ink of choice and your writing tool of choice write your message on your valentine. There are a number of options you can experiment with for either the ink or your writing tool. Have fun playing around with it!! (We had good luck with lemon juice and a paint brush).

*We recommend that you run a test first to see how your ink and paper change color with heat.*

- Let your ink completely dry, it should be invisible. (Some acid sources may have a little color to them. Orange or grapefruit juice may leave a slight tinge of color).

- Use a heat source like an oven pre-heated to 400 F. Or with adult supervision you may use a candle to develop the message. If you use the candle we recommend you do this over the sink or in the bathtub in case the paper catches on fire.

Text was going to say “Secrets Come Out When Things Heat Up”. Unfortunately the paper caught on fire a few times. Image Credit: The Mariners’ Museum and Park

The oven will take a couple of minutes to develop the message. The longer it sits the darker the message, but the rest of the paper also gets darker. Using the candle you have to carefully heat the back of the paper with the flame, it takes some practice.

- Once you have perfected how you write with invisible ink, make your Mariner’s Valentine and send it to them.

Make sure to send some helpful instructions on how they get their message!

Share your Valentines with us on Facebook or twitter using #iamamariner !!!!