When Union general Benjamin Franklin Butler arrived at Fort Monroe, Virginia, he immediately sought to show the Virginians that his troops could go anywhere they wished on the Peninsula. On May 23, 1861, Butler sent Colonel J. Wolcock Phelps into Hampton. The Union troops marched into the town and then returned to the fort. In the ensuing confusion, three men enslaved by Colonel Charles King Mallory escaped. Frank Baker, James Townsend, and Shepard Mallory seeking their freedom, made their way onto Fort Monroe. Butler refused to return the runaways and called them ‘Contraband of War.’ Their decision helped transform the Civil War into a conflict between the states and a struggle for freedom.

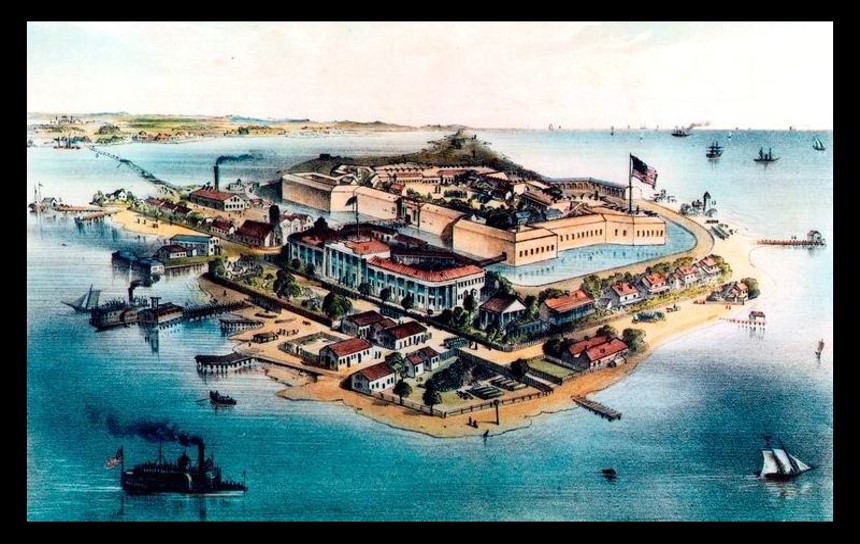

FORT MONROE: THE KEY TO THE SOUTH

Winfield Scott recognized Fort Monroe as key to his policy of bringing his native state of Virginia back into the Union. He believed that the enforcements he had already sent and the additional troops he intended to transfer to the Peninsula necessitated a change in command. Scott needed a high-ranking officer to command the growing number of troops on Old Point Comfort. He wanted an aggressive leader who would actively contest Confederate positions threatening the Hampton Roads anchorage and secure the Peninsula as an avenue of approach against Richmond. Scott’s selection was somewhat of a surprise. Instead of detailing a veteran officer to this critical post, he chose the sharpster lawyer and slick politician turned militia officer, Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN BUTLER

Butler was born in Deerfield, New Hampshire, on November 5, 1818. His father had fought during the War of 1812, and his grandfathers fought during the French and Indian, and Revolutionary wars. Ben Butler dreamed of a military career; but, he was frail and had a cast in one eye. He was not well suited for West Point. Instead, he attended Colby College and passed the bar in 1840. Almost from the start, Butler acquired the reputation of being a bold, astute, and none too scrupulous lawyer. He gained great success and wealth; he purchased Middlesex Mill in Ludlow, Massachusetts, and was named to several bank boards.

SEEKING POWER

Yearning for political power, Butler joined the Democratic party. He was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1852 and the state senate in 1858, making him a true power in his party. During the 1860 election crisis, he believed the Southern states had the constitutional right to practice slavery. He gave his support to the nominations of Jefferson Davis and John Cabel Breckenridge.

Abraham Lincoln’s election put in motion the secessionist movement. Butler knew that secession meant war. Ben Butler knew that the North would fight for the preservation of the Union, which he saw as his opportunity for even greater power.

OH, TO BE A SOLDIER

- B. F. Butler had always dreamed of being a soldier and had joined the Massachusetts militia as a private in 1838. Due to his political connections, he was named a brigadier general of the Massachusetts militia in 1857. When Lincoln called for volunteers after the capture of Fort Sumter, Butler made some backroom deals hoping he would be named commander of the first Massachusetts troops taking the train south to protect Washington, DC.

Butler would thwart the Maryland secessionist movement following the April 19 Baltimore Riot. Eventually, he occupied Annapolis, Maryland’s capital, and Baltimore. His determined actions helped maintain that slave state under Union control. This gave Butler immediate notoriety. President Lincoln quickly named him major general. The next day, Butler received orders to report to Fort Monroe, Virginia, to assume command of the post.

A NEW OPPORTUNITY

The bold Butler went to Washington to pick up his commission in person. He met with President Lincoln, stating he was unsure he should accept this promotion. Butler believed that his new assignment was a reproof for his actions in Maryland. He refused such a demotion and threatened to return home and resume his law practice. Lincoln and other cabinet members assured Butler that his new duties included the command of territory in a 60-mile radius around Fort Monroe.

The cocked-eyed and corpulent politician, recognizing that this new assignment was another opportunity to further his political ambitions, accepted the command. The next day, Butler met with general-in-chief Winfield Scott, who confirmed Butler’s new appointment as commander of the Union Department of Virginia and North Carolina. “Boldness in execution is nearly always necessary,” the old general advised the newly minted major general. Butler intended to immediately act upon this advice once he arrived at Fort Monroe.

AN UNUSUAL RISING STAR

During the war’s first month, Butler had created a sensation. Torch-lit parades were held in his honor throughout the North, and despite his disagreement about the occupation of Baltimore with General Scott, President Lincoln needed Butler. The Republican administration desperately required his Democratic party affiliations to broaden public support for the war.

Yet, Butler did not look like a general. A British journalist described Butler as a “stout, middle-aged man, strongly-built, with course limbs, his features indicative of a great shrewdness and craft, his forehead high, the elevation being of some degree due perhaps to the want of hair, with a strong with obliquity of vision, which may perhaps have been caused by injury as the eyelid hangs with pendulous droop over the organ.”

Another observer described Butler after his triumphal entrance into Baltimore: “I found him clothed in a gorgeous military uniform adorned with rich gold embroidery. His rotund form, his squinting eye, and the peculiar puffs of his cheeks made him look a little grotesque. …Officers entered from time to time to make reports or to ask for orders. Nothing could have been more striking than the air of authority with which the General received them, and the tone of court premptorious peculiar to the military commander on the stage, with which he expressed his satisfaction or discontent, and with which he gave his instructions. And, after every such scene, he looked around with a sort of triumphant gaze, as if to assure himself that the bystanders were duly impressed.”

BE ‘BOLD’

Butler arrived on the Old Bay Line steamer, Adelaide, on May 22, 1861. The next day, he decided to break the informal truce between the Federal and Confederate forces on the Peninsula. Butler ordered Colonel John Wolcott Phelps, 1836 West Point graduate, a veteran of the Seminole and Mexican wars, and an ardent abolitionist, to take his 1st Vermont Volunteer Regiment into the town of Hampton. His orders entailed that he was to close the polls in order to disrupt the vote on the ordinance of secession that was to occur that day.

HAMPTON, VIRGINIA

Hampton was a small town of about 1,000 residents; however, the Confederates had not attempted to develop defenses because of the community’s proximity to Fort Monroe. Hampton was barely defended by a Confederate camp located just outside the town, commanded by Major John Baytop Cary. Cary was a graduate of the College of William & Mary and superintendent of the Hampton Military Academy.

This “Camp of Instruction” contained only 130 poorly armed men and was unable to block any Union advance. Cary already knew that the Federals would eventually march into Hampton. He had made plans to burn the Hampton River Bridge to thwart any such movement.

STEP OF THE TYRANT’S HEEL

When Phelps’s Vermonters approached Hampton that afternoon, Cary went into action. Unfortunately, he could not locate either the firing party or the combustibles. Cary somehow started a small fire, yet it was slow to set the span into flames. Phelps saw the wisps of smoke rise from the bridge and ordered his men to the double-quick to capture the bridge. Cary learned that the Federals had no hostile intent, “but simply … to reconnoiter.” With these assurances that neither the town nor its population would be molested, some Hamptonians and Vermonters joined Cary to extinguish the flames. Cary then moved his men away from Hampton. Phelps marched into town, closed the polls, and returned to Camp Hamilton outside of Fort Monroe. Once the Federals left, Hampton residents immediately reopened the polls and overwhelmingly voted for secession — 360 to six.

PEACEFUL INTERACTIONS BETWEEN NORTH AND SOUTH

Phelps’s “reconnoitering expedition” achieved little, it appeared, beyond stopping the destruction of the Hampton River Bridge and reinforcing that Federal troops could march whenever and wherever they wished throughout the lower Peninsula. Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Stoddard Ewell, an 1832 West Point graduate, former president of the College of William & Mary, and commander of the Confederate troops on the Peninsula, had rushed toward Fort Monroe to ascertain Butler’s intentions. Ewell was captured en route by Federal pickets.

Major Cary traveled to the fort to secure Ewell’s release and to discover from Butler “how far he intended to take possession of Virginia soil, in order that I might act in such a manner as to avoid collision between our scouts.” Butler advised that the Federals merely needed more land for their encampments and inferred that they would not act aggressively unless assaulted by Confederate troops. Cary then secured Ewell’s release and was immediately ordered by Ewell to destroy the Hampton River Bridge. Nevertheless, the May 23, 1861 expedition had far-reaching political implications that would forever disrupt the antebellum Peninsula.

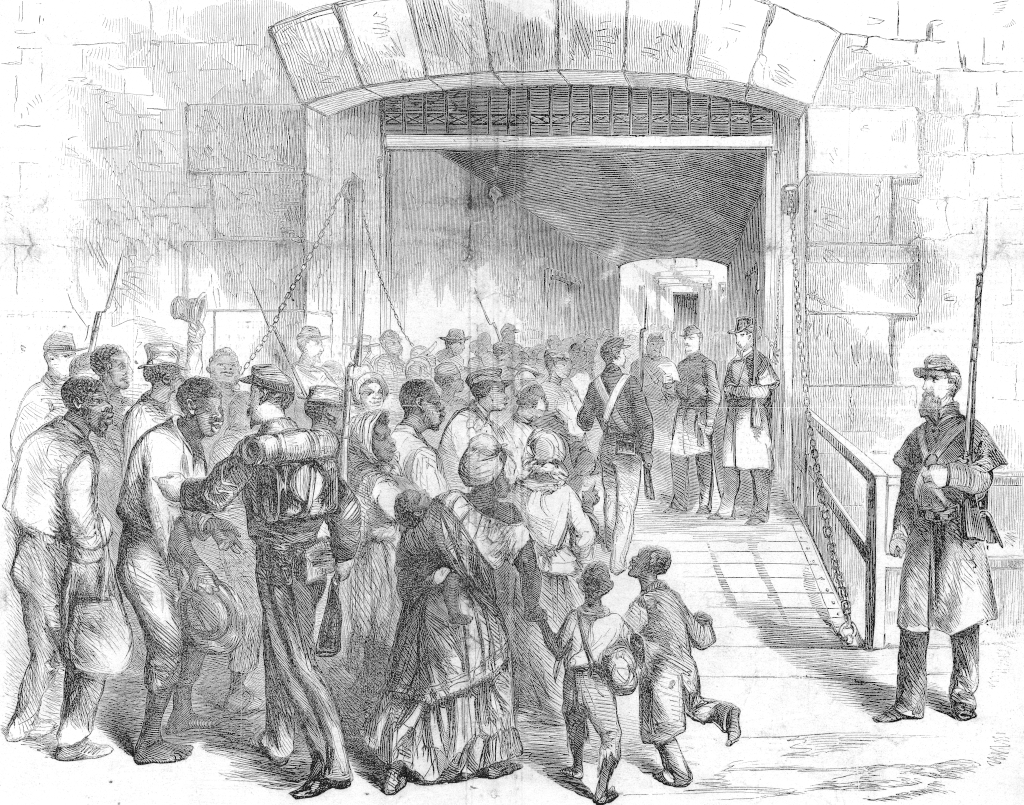

RUNAWAYS

While some Hampton residents may have been in an uproar over the Union advance, most African Americans were overjoyed. They welcomed the Bluecoats with “Glad to see you.” This first encounter of bondsmen and Union soldiers prompted three men of African descent, Sheppard Mallory, Fran Baker, and James Townsend (enslaved by Hampton resident and commander of the 115th Virginia Militia Regiment, Colonel Charles King Mallory), to take “advantage of the terror prevailing among white inhabitants” and escape into Union lines.

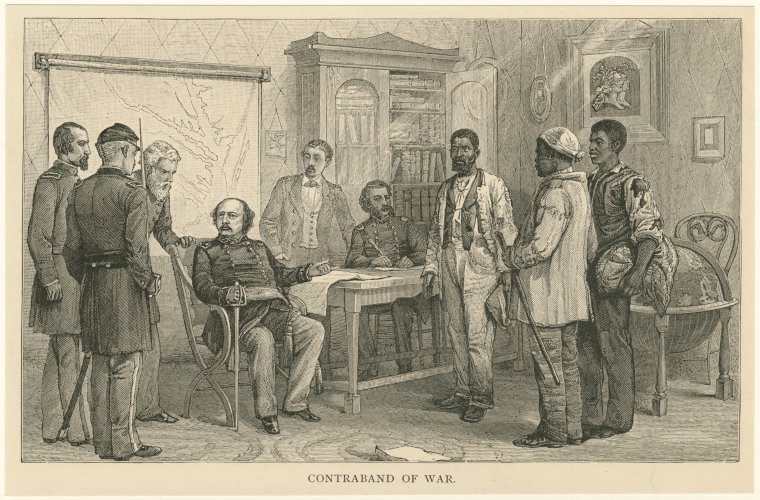

CONTRABAND OF WAR DECISION

Before Butler could decide what to do with these runaways, on May 24, 1861, Major Cary returned to Fort Monroe to retrieve those three men enslaved by Col. Mallory. Cary demanded the return of Mallory’s property, citing the Fugitive Slave Law as justification.

Realizing that these enslaved men were being used to build nearby Confederate fortifications on Sewell’s Point, Butler refused Cary’s request. He informed Cary that since Virginia now considered itself an independent nation, his “constitutional obligations’’ were null and void. Butler further noted that because Virginia was at war with the United States, he intended to take possession of whatever property he needed.

Since enslaved people were considered “chattel property,” Butler called Mallory’s bondsmen “contraband of war” and assigned them to support Union operations in Hampton Roads. This was the Civil War’s first step from being a war between the states into a war about freedom.

DECISION’S IMPACT

The “contraband of war” decision brought slavery to the forefront as a wartime issue. Even though President Abraham Lincoln initially thought to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act so as not to disrupt the Border States, the war now grew far beyond an effort just to preserve the Union. Ben Butler immediately recognized the political and economic implications.

Instead of the enslaved supporting the Southern economy and war effort, Butler turned this Southern asset into a Union benefit. He put the contrabands to work, building fortifications, and other related duties. Butler believed that the work of contrabands was a good return for the food and shelter the Union provided for them.

CONFISCATION ACT

The Union general’s radical opinion was often called “Butler’s Fugitive Slave Law.” President Lincoln did not openly embrace it; however, the Radical Republicans in Congress did. On August 16, 1861, Congress formally approved Butler’s decision when the Confiscation Act was passed. The act “confiscated any slave who had been used for military service against the United States” and prompted the establishment of contraband communities such as the Port Royal Sound Experiment in November 1861 and the Roanoke Island Experiment in Spring 1862.

FREEDOM’S FORTRESS

On May 27, Butler informed General Winfield Scott that since a dozen enslaved persons had escaped from Sewell’s Point to become contrabands, the value of the formally enslaved persons in Union hands exceeded $60,000. “The negroes came pouring in day by day,” Butler wrote. “I found work for them to do, classified them and made a list of them so their identity might be fully assured and appointed a commissioner of negro affairs.”

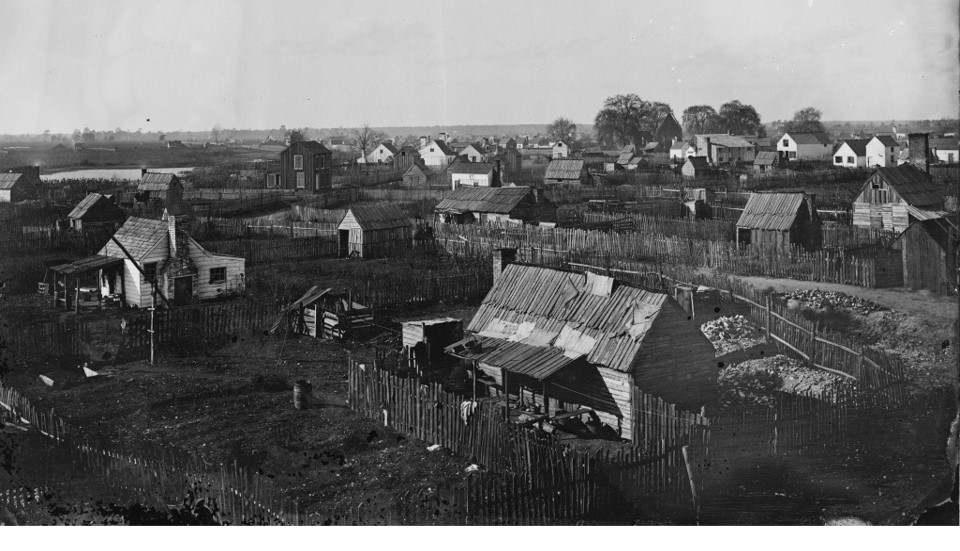

The influx of Union troops and contrabands overwhelmed Fort Monroe as it was not designed to hold so many men. Accordingly, Camp Hamilton, on the Clark and Segar farms, was established for the overflow of Union units like the 1st Vermont and 5th New York-Duryea’s Zouaves. Next to this camp, contrabands established their first community and built a church. It was initially called “Slabtown.” When Union troops occupied Newport News Point to create Camp Butler, the armed camp quickly became another magnet for escaping enslaved people. More contrabands found their way to Newport News Point. This prompted Butler to build “two commodious buildings” to house these contrabands.

Once the contrabands began establishing their communities, they went to work for the US Army for $2 a month. Many became officer’s servants or guides for Union movements throughout the Peninsula. Others were more inventive, oystering, fishing, and growing crops to sell food to the soldiers at informal markets.

‘A GREAT THIRST FOR KNOWLEDGE’

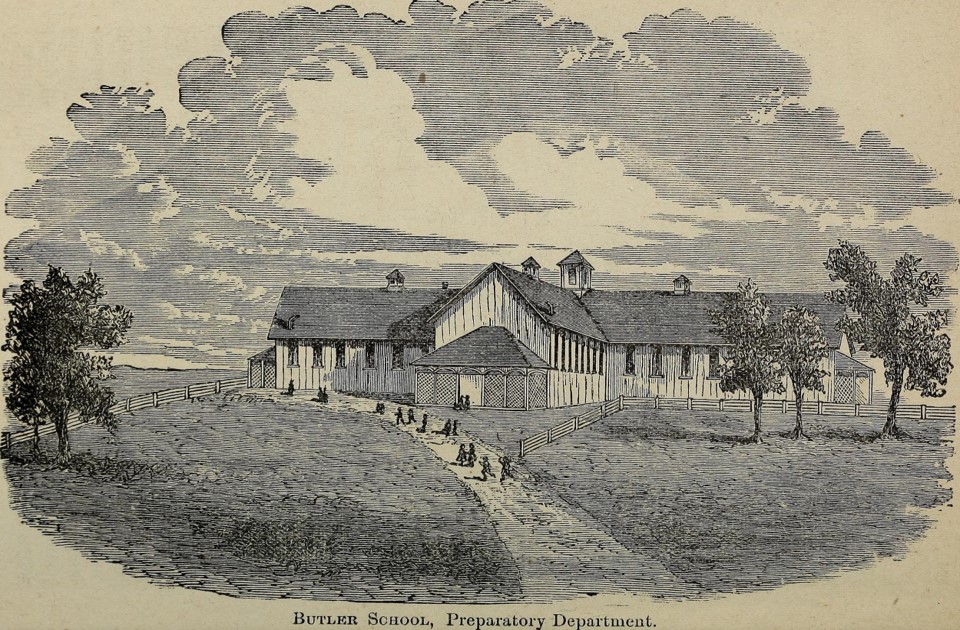

As soon as news of the Contraband of War Decision reached the North, the American Missionary Association (AMA) ministers and teachers recognized the excellent opportunity for educating the formerly enslaved people, creating several contraband schools in Hampton.

The AMA was a New York-based philanthropic society. Reverend Oliver was one of the first missionaries to arrive at Fort Monroe just days after Butler’s decision. He later remembered passing by the “fortress chapel and adjacent yard, where most of the contraband tents were set…One young man sat on the end of a rude seat ‘with a little book in his hand.’ It had been much fingered, and he was stooping down towards the dim blaze of the fire to make out the words….Where he had learned to read I know not, but where some of his companions will learn to read I do know.”

Reverend Lewis C. Lockwood of the AMA noted with joy that the contrabands had “a great thirst for knowledge…parents, and children are delighted with the idea of learning to read.”

MARY PEAKE

Mary Smith Kelsey Peake was a free mulatto born in Norfolk in 1823. She attended school in Alexandria and returned to Tidewater Virginia, eventually moving to Hampton in the 1850s.

Peake was the only free Black teacher of enslaved people of African descent and free Blacks in antebellum Hampton. She violated a slave code established after Nat Turner’s Rebellion which forbade the teaching of slaves to read and write.

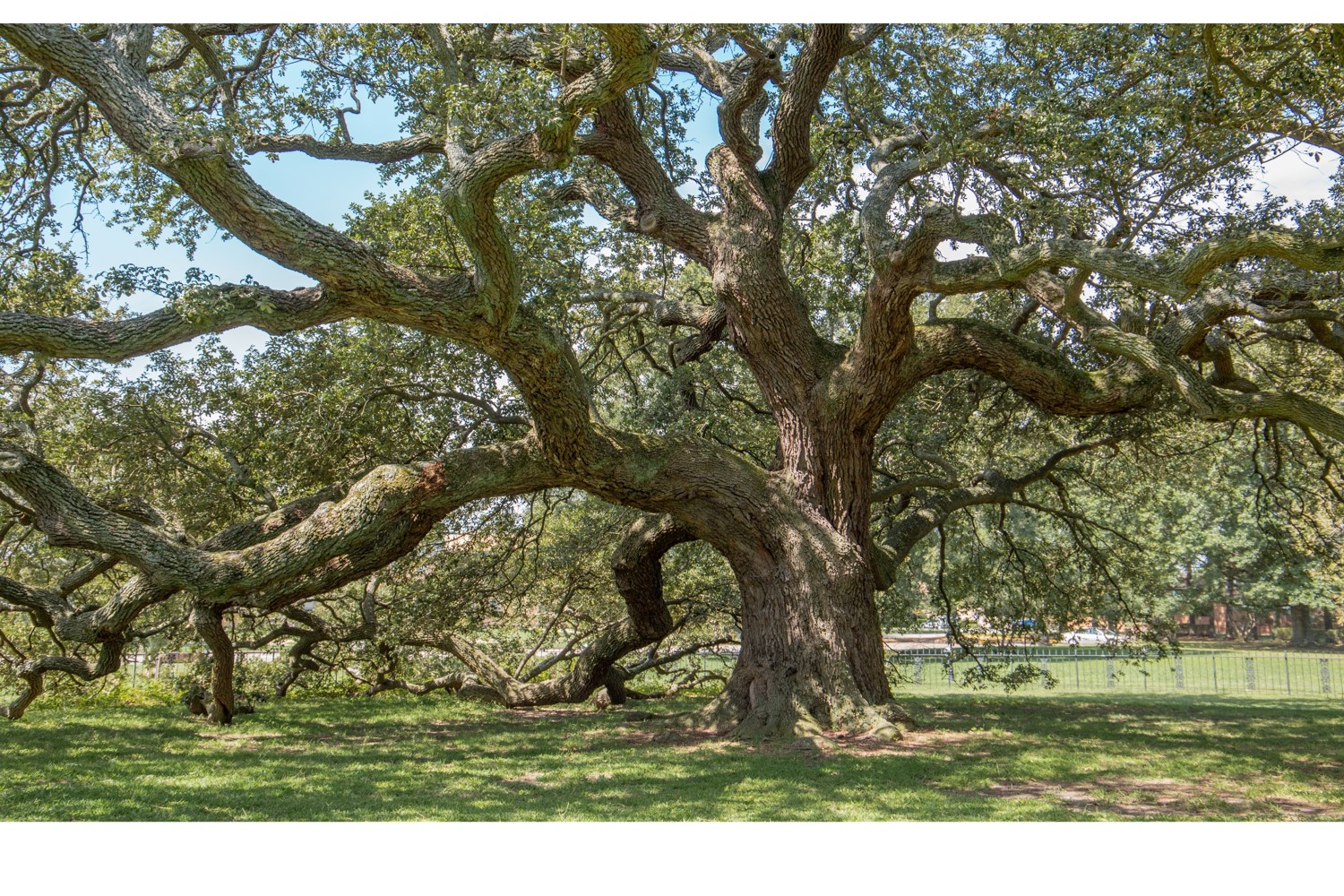

She worked as a dressmaker during the day, using her home next to the Hampton Military Academy to teach African Americans at night. When the AMA arrived on the Peninsula, Peake was already teaching students under what is now known as the Emancipation Oak on today’s Hampton University campus. The AMA provided her with a building known as Brown’s Cottage, where she taught 50 children during the day and 20 adults at night. Sadly, Mary Peake died of consumption in 1862.

Other schools were created nearby. Peter Herbert, the caretaker of former president John Tyler’s summer home “Villa Margaret,” operated a school for contrabands in the building’s basement. Other schools, supported by the AMA, were one-room schoolhouses. One teacher would teach all subjects with anywhere from 50 to 100 pupils.

In 1863, Butler allocated Army funds to build the Butler School, operated by the AMA. A large frame building in the shape of a Greek cross, Butler School could handle up to 600 students.

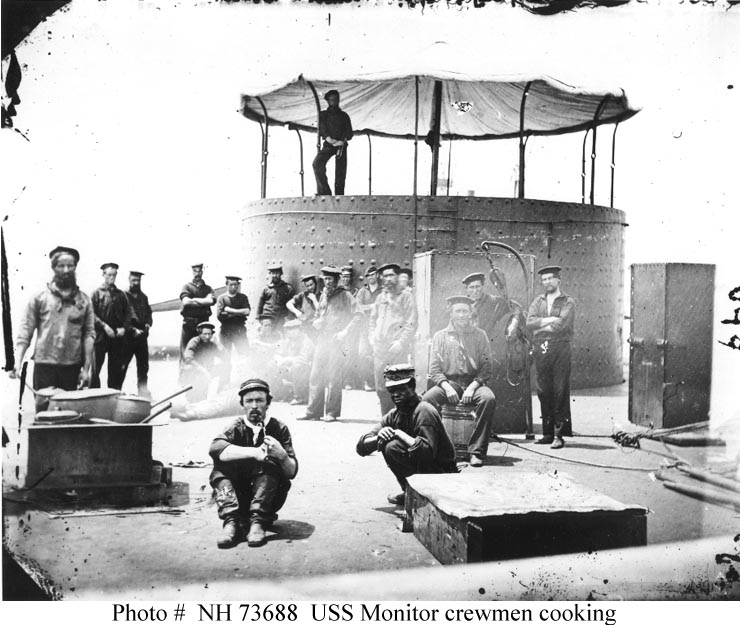

IN THE NAVY

Many contrabands wanted to serve in this conflict to expand the nation’s concepts of freedom. While the US Army refused Black enlistment in 1861, the US Navy was color blind. It had maintained a color-blind enlistment policy since the Revolutionary War. The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron’s primary base was Hampton Roads, and the squadron’s ships were constantly seeking crew members. Contrabands took advantage of these opportunities.

Sixteen formally enslaved African Americans made up the entire crew of USS Minnesota’s aft pivot gun crew. This steam screw frigate’s commander, Captain Gershon Jacques Henry Van Brunt, praised his gun crew: “The Negroes fought energetically bravely–none more so. They evidently felt that they were working on the deliverance of their own race.”

Several contrabands found their way onto USS Monitor. One was First-Class Boy, Ship’s No. 53, Siah Carter (Hulett). He escaped from Shirley Plantation. His enslaver, Colonel Hill Carter, warned his enslaved people that if they went on board any of the “Yankee ships” then cruising in the James River, “the Yankees would carry them out to sea & throw them overboard.” When Monitor was anchored off Shirley Plantation in the James River, Siah made his decision.

He took a small skiff on the evening of May 18, 1862, and rowed his way to the ironclad. There he found not only his freedom; but also a way to help the Union achieve victory.

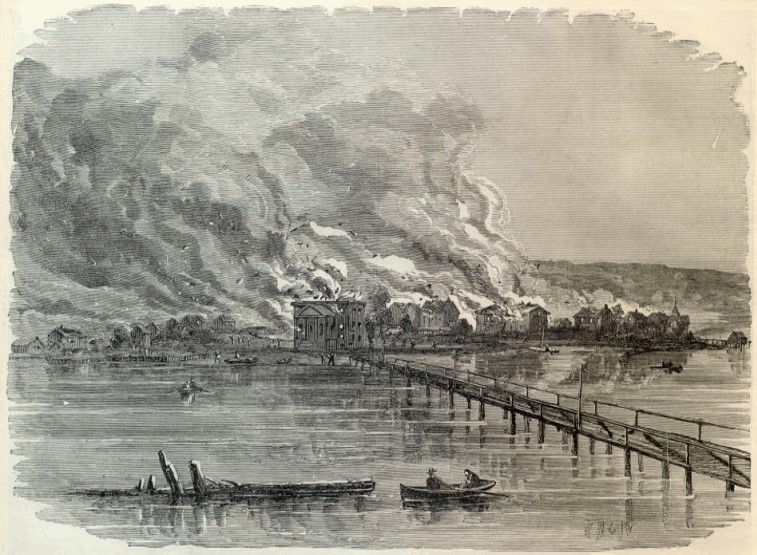

BURNING OF HAMPTON

Most of Hampton’s white citizenry had fled the town when the Union occupied Newport News Point. Brigadier General John Bankhead Magruder was the Confederate Army commander of the Peninsula and wished to contest Camp Butler on Newport News Point on August 6, 1861. While feigning an attack on the Federal position with 5,000 soldiers, a copy of the New York Tribune was found at an abandoned Union picket and given to Magruder.

The newspaper contained an article stating that Butler intended to use Hampton to house contraband and Union soldiers. Determined not to allow Hampton to be used by the Federals for winter quarters or to become “the harbor of runaway slaves and traitors,” Magruder realized the town’s proximity to Fort Monroe would not allow the Confederates to hold the town, so the Confederate general, with the agreement of local soldiers, decided to burn Hampton.

On the evening of August 7, 1861, Confederate soldiers began to set the town on fire. Sergeant Robert S. Hudgins II of the Old Dominion Dragoons recounted the scene: “As the smoke ascended toward the heavens I was reminded of the ancient sacrifices on the altar to many deities, and I thought of how my little home town was being made a sacrifice to the grim god of war.”

THE GRAND CONTRABAND CAMP

Hampton was now just a bleak forest of burned chimneys and heaps of smoldering ruins. Nevertheless, upon these ashes, formerly enslaved persons created the largest contraband community on the Peninsula, the Grand Contraband Camp. Also known as “Slabtown,” people built makeshift homes upon the foundations of ruined buildings. Its existence was the very circumstance that Magruder wished to stop when he ordered the town’s destruction. With assistance from US Army engineers and the AMA, contrabands rebuilt the Elizabeth City Courthouse on King Street in Hampton, establishing it as the largest school in the Grand Contraband Camp.

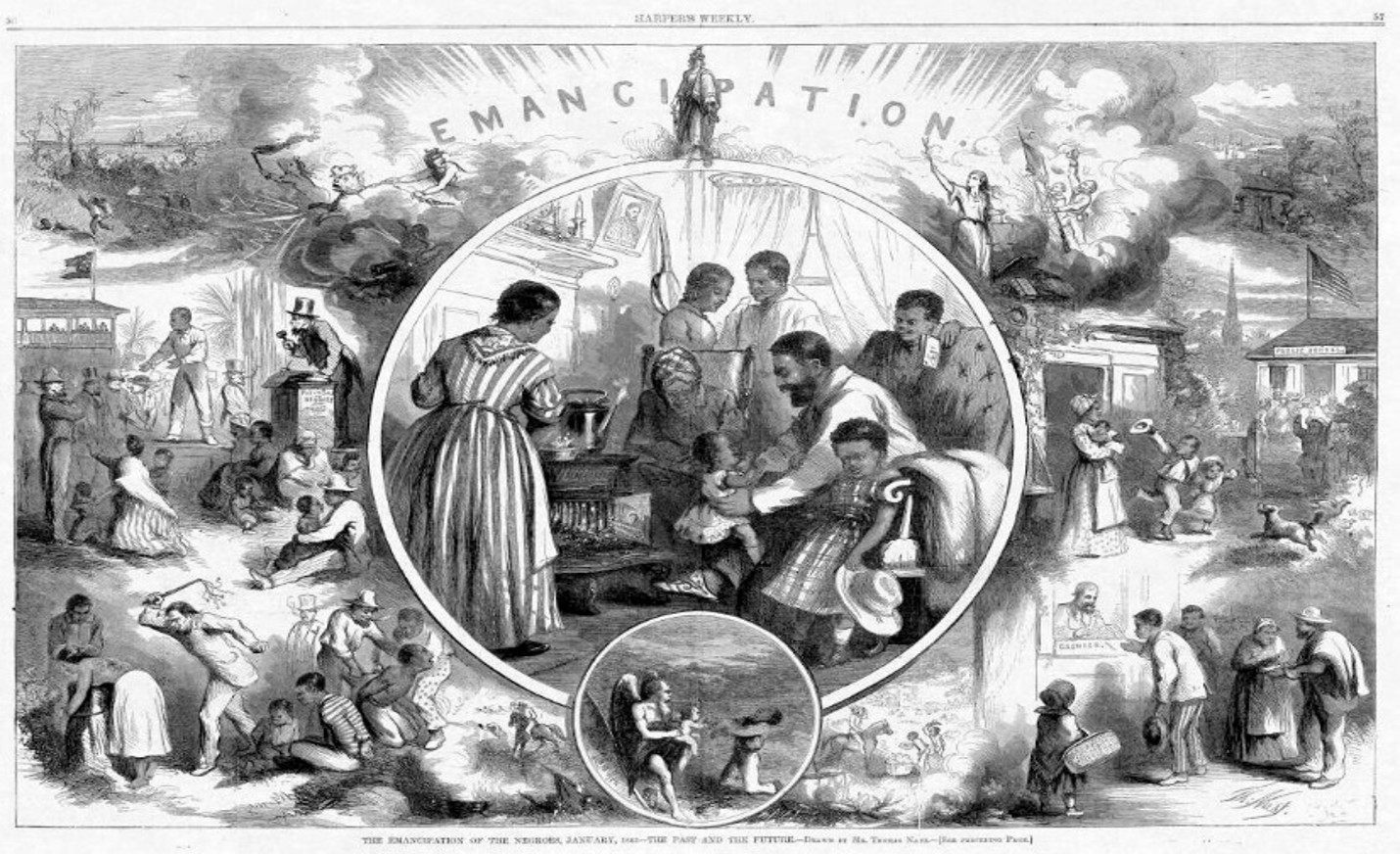

EMANCIPATION OAK

The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order issued on September 22, 1862, by President Abraham Lincoln. The Proclamation became law on January 1, 1863. The first recorded public reading of this “liberation” document in the South occurred just outside Slabtown Contraband Camp under the bows of a live oak now known as Emancipation Oak. Most of the attendees were contrabands and AMA teachers, who believed that this document gave them freedom. Yet, it did not.

The Emancipation Proclamation excluded counties in Virginia, South Carolina, Louisiana, and North Carolina, and in the new state of West Virginia. No slaves were freed in the Border States, where slavery was still legal. It only referred to those enslaved persons in land controlled by the Confederate government.

Nevertheless, those residents of Slabtown, the Grand Contraband Camp, and other contraband camps in Norfolk, Portsmouth, and York County, knew that the Emancipation Proclamation was also about them. They were jubilant over the fact that they had learned to read and found employment or other economic activity when they became contrabands. Now, it was confirmed to every contraband and enslaved person that the war’s final course would end slavery.

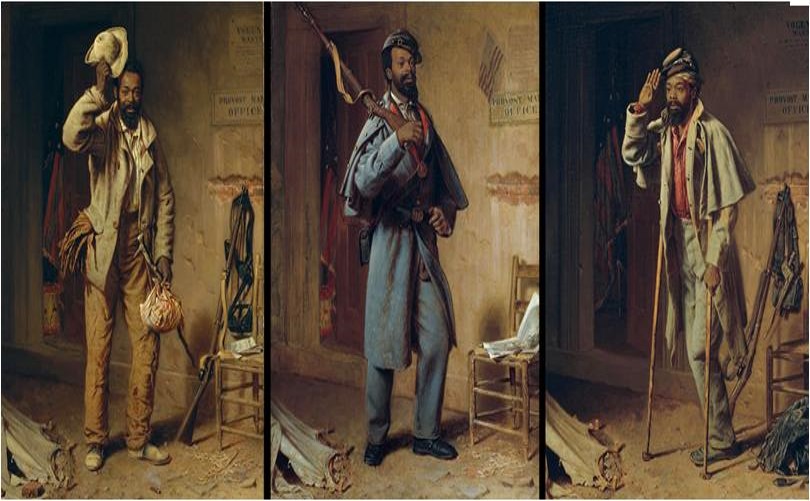

UNITED STATES COLORED TROOPS

Many Union generals recognized that every contraband that came into Federal lines took manpower away from the Confederate economy and gave this resource to the United States’ war effort. The once enslaved abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, pestered Lincoln to recruit African Americans. Douglass wrote, “Let the Black man get upon his person, US. Let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulders and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth, or under the earth, that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship in the United States.”

The Militia Act of 1862 enabled the recruitment of African Americans for service in the US Army as members of the United States Colored Troops. White officers commanded these USCT soldiers, and the Black servicemen could only rise to the rank of Sergeant Major.

These regiments were created to serve in combat and did so with great valor. The USCT fought during such critical engagements as the battles of Honey Hill, Fort Wagner, the Crater, and New Market Heights. More than 180,000 African Americans served in USCT units, and 14 received the Medal of Honor. Many had connections to the contraband camps in Tidewater Virginia.

Corporal Miles James escaped from Princess Anne County. He made his way to Camp Craney Island, established for the overflow of contrabands from Norfolk, Princess Anne County, and Nansemond County. The opportunity of enlistment in the USCT prompted Cpl. James to join the 36th USCT. He fought during the September 29, 1864 Battle of New Market Heights. While advancing against the Rebel works, he was shot and ‘“had his arm mutilated making immediate amputation necessary. He loaded and discharged his piece with one hand and urged his men forward.”

Other contrabands served at this battle. Edward Ratcliff became a contraband when the Union occupied Yorktown; he enlisted in the 38th USCT. He received a Medal of Honor as he “gallantly led his company after the commanding officer had been killed.’”

Twelve USCT soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor due to their service at New Market Heights. Two of these men, Alfred B. Hilton and Robert Veale, are buried in the Hampton Veterans’ Cemetery.

LET FREEDOM RING

Ben Butler did not come to Hampton Roads to free slaves; nevertheless, his astute legal mind set a precedent. His Contraband of War decision changed the very purpose of the war, transforming it from a war between the states into a conflict defending the United States’ concept of freedom. It was the beginning of the nation’s struggle to secure Civil Rights and equality for all Americans.

Sources

Yorktown’s Civil War Siege: Drums Along the Warwick, John V. Quarstein and J. Michael Moore. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012.

The Monitor Boys: The Crew of the Union’s First Ironclad, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011.

Fort Monroe: The Key to the South, John V. Quarstein and Dennis Mroczkowski. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1999.

Civil War on the Virginia Peninsula, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1997.