What do a Battleship, 1950, mud, high tides, a Hudson River Ferry, a T-shirt, and a UFO all have in common?

To find out how they interconnect, let’s start with the Battleship USS MISSOURI (BB-63). In 1950, the ship was already famous for her participation in WWII, and because the surrender that ended the war was signed on her deck. MISSOURI was nicknamed the “Mighty Mo” by her crew, but she was also known as the “Big Mo” to the public and in news reports. She would soon live up to them both names when she managed to get into a mighty big mess.

It all began on January 17, 1950. MISSOURI left Norfolk Naval Base and headed towards the Atlantic Ocean to begin a routine training cruise to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Her Captain, William D. Brown, was new to the battleship, having just joined the crew in December. While he was an experienced naval officer, his previous commands had been submarines and destroyers and he had been on shore duty since the end of World War II. Although Captain Brown had taken MISSOURI on a few short trips off the coast of Virginia after he took command, he was essentially unfamiliar with the battleship and this would be his first time taking her out for a cruise.

The Navy had set up an acoustic range to capture the signature sounds made by ships and it was close to MISSOURI’s departure point. Captain Brown had been asked to take a previously unplanned trip through the range on his way out, and he was told that buoys had been set up to mark the area. This was important since the range was very close to shallow water.

Things started to go wrong pretty quickly. It turned out that some of the buoys had been removed and the navigational charts hadn’t been updated with that information. Not all the ship’s officers knew about the plan to take MISSOURI through the range, and some of them only heard about it just before the battleship headed in that direction. Another complication was that the range area was close to a fishing channel that was also marked with buoys.

Brown spotted what he thought was the marker for the right edge of the acoustic range and ordered the battleship to the left of the buoy. He ignored warnings by the navigator and the executive officer’s attempts to alert him, not realizing until much too late that he had made a mistake. Even though the tide was unusually high that day, MISSOURI was heading into the fishing channel and shallow water.

At 8:17 am, the “Mighty Mo” hit a sandbank in the Chesapeake Bay, about a mile and a half from Thimble Shoal Light and a mile off Old Point Comfort. The battleship, traveling at 12.5 knots, plowed 2,500 feet into the sandbar, bottoming out the ship and lifting her out of the water about seven feet above the waterline.

Now the ship was stuck just off the Army base at Fort Monroe, close to Thimble Shoals Lighthouse, the shipping channel, and within sight of the Naval Base.

Within a couple days, articles would start appearing in newspapers all across the country that “Mighty Mo” or “Big Mo” had grounded. These articles were quickly followed by reports of multiple failed attempts to free the battleship over the next two weeks. Bringing not only amusement to the onlookers and readers, but also quite a bit of humiliation to the Navy. Army personnel, finding the entire situation hilarious, discovered a new hobby. Partaking in the amenities of the Fort Monroe Officer’s Club while writing letters and composing telegrams containing suggestions on how to free the battleship. The public also got involved and sent suggestions too. The Navy was inundated with ideas, including one from a five-year-old boy in Indiana who told them they just needed to fix the bottom of the ship so she could float again.

After numerous failed attempts using a large number of tugboats, military vessels, small explosive charges, dredging, large cables, and other methods, MISSOURI was finally refloated on February 1, 1950, during another unusually high tide. Even after the ship was freed, the jokes continued. For most of 1950, anytime an accident involved a large amount of mud, the nickname “Mo” surfaced again. A situation was a “Big Mo,” like a plane that slid off an icy runway into the mud. A car that imitated the “Big Mo” or two boats that went aground in mud off New Jersey on the same day and the efforts to free them was named “Operation Big Mo”.

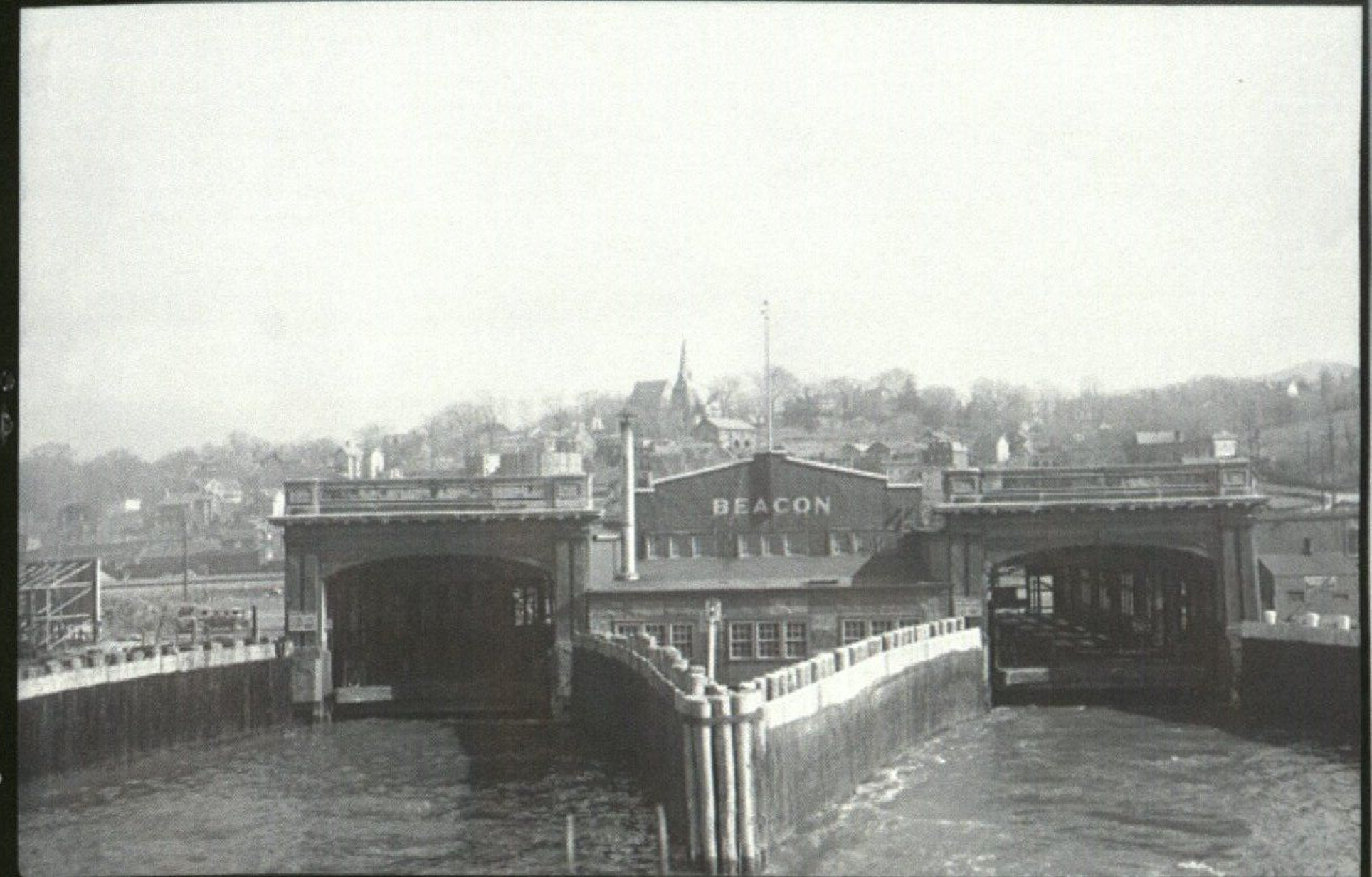

So now on to April 1950, the ferryboat and a point on the Hudson River in New York. There, two cities are located across from each other on the river. Newburgh, located in Orange County, and just one and a half miles away, Beacon in Dutchess County. Both cities are about 55 miles from the New York metropolitan area. The Newburgh-Beacon Ferry system provided transport between the two cities with three commuter ferries named ORANGE, DUTCHESS, and BEACON. Usually, two of the three boats were in service at the same time, each moored at the opposite side of the river and they passed each other in the middle during their runs. The first run of the day began around 7am and it took about 15 minutes to reach the other side of the river.

DUTCHESS was a 160-foot, 400-ton vessel capable of carrying 400 passengers and 30 cars. Captain Dan Carroll was in charge and by 1950 he had 43 years of experience with the ferry service. Unlike Captain Brown on MISSOURI, Carroll was very familiar with the capabilities of his boat.

On April 10th, DUTCHESS started out from Beacon on her first run of the day carrying 22 commuters, a couple vehicles, and her regular crew aboard. The weather was nice with good visibility and the water was near high tide. But just five minutes after setting out, and only 300 feet from the dock, DUTCHESS struck a mud bank and ran aground. Captain Carroll tried to get the ferry out of the mud by using the engines, but after a while, he had to admit defeat. He ordered the crew to row the passengers back to shore in the lifeboats, and by 9:30 all the commuters were safely back at the dock.

ORANGE arrived at Beacon dock about 7:15 am and after discharging her commuters, she remained there until all of DUTCHESS’ passengers were safely ashore. Then her Captain moved his boat to the grounded Ferry and tried to pull it out of the mud using a cable. But after a few tries, ORANGE backed into an underground rock ledge, damaging her rudder and making it impossible to steer the boat. Now both ferries were out of commission.

Because DUTCHESS and ORANGE were the only two ferry boats operating that morning, it meant all ferry service between Newburgh and Beacon had now ceased. This did not go unnoticed by the growing number of commuters on both sides of the river who were waiting for rides. By now they numbered in the hundreds. Frustrated at the situation, loud voices at both docks began shouting “We need a bridge! We need a bridge!”

The remaining ferry, BEACON, started the process of firing up her engines and limited ferry service was available by 10 am. The ferry company then made some calls to New York City to request a tug and Tugboat SHELIA MORAN arrived late afternoon, just before high tide. For more than four hours the tug struggled to free DUTCHESS as spectators lined the dock to watch. Despite the tug alternately pushing and pulling the ferry, it remained stuck in the mud and as the tide begins to drop, it became more and more noticeable that the ferry was also leaning about 45 degrees to her port side. Finally, around 10pm, the tide was so low that, even if the SHELIA MORAN could manage to free the ferry, the water level was too low to float her off the mud, and plans are made to try at the next high tide the next morning.

While all this was happening, the Associated Press put out a news story on the grounding, comparing the fate of the ferryboat to a certain battleship that also got stuck in the mud earlier in the year. Headlines in the afternoon papers report that the Hudson River Ferry “who imitated the “Big Mo”” got stuck on a mud bank. The news soon spreads as far away as Florida and Alabama.

No doubt the comparisons were also being made at Beacon dock. A local clothing company, Allison Manufacturing, made printed t-shirts to commemorate the grounding. Since Allison Manufacturing specialized in children’s clothes, that’s what size shirts they printed. Soon children standing with their parents at the dock were watching the action while wearing shirts that featured a cartoon-like image of the tilted ferry sitting on mud. The bright red and black design was surrounded by bold lettering proclaiming “LITTLE MO CAN’T GO”, “STUCK IN HUDSON MUCK” and “IF THE NAVY CAN DO IT SO CAN WE”.

Overnight a second tug, KATHLEEN MORAN, joins her sister boat and with one tug pulling and the other pushing, they finally managed to free DUTCHESS just after 7:00 am on April 11th. After undergoing an inspection at the dock it was determined that the damage to the ferry was relatively minor and the boat was determined to be seaworthy (river worthy?) and put back into service. So normal service between Beacon and Newburgh resumed by 8:15am with DUTCHESS and BEACON running the route. ORANGE had to be dry-docked for about three days for repairs to her rudder and the damage to Dutchess would be repaired later in the year when she went into drydock in November 1950.

The “Big Mo” went aground in Hampton Roads in January 1950 due to errors committed by her Captain. But why did a ferry with an extremely experienced Captain who knew exactly what his boat’s capabilities were, manage to ground his vessel? The ferry company bosses definitely wanted to know. Very quickly, Charles Templeton, one of the company’s superintendents declared that the Ferry must have been seriously off course and that he would be looking into the reason why that happened. Others had different ideas. Men who worked on the river suspected the tide. They noted that while the ferry went aground during high tide, the water level wasn’t quite as high as normal. One rumor going around was that the ferry had snagged on a UFO that had crash-landed in the Hudson River the evening before the grounding.

For many people, a crashed UFO seemed like a very plausible explanation. The ferry’s grounding occurred about 18 months after a weather balloon, a UFO, or whatever it was, crashed in Roswell, New Mexico. Speculation was rampant over whether or not UFOs existed. Movie theaters were showing Science Fiction films. Additionally, a multitude of newspaper articles seen all over the country debated or made claims about the existence of UFOs and reported sightings. In fact, a search through newspaper archives shows that a number of New York newspapers included at least one article, movie listing, or radio program announcement on the subject of UFOs on 30 of the 31 days in March 1950, the month before DUTCHESS went aground, and the articles continued into April, before and after the accident. There were, however, no sightings or crash landings reported in the newspapers before, or on, the day of DUTCHESS’ grounding.

It is unclear what punitive action the ferry company took against the ferry’s captain. There don’t appear to be any follow-up news accounts on the grounding past April 12th. But according to his obituary, Captain Carroll wasn’t discharged and he retired from the ferry company in 1955.

So, what do mud, a Hudson River Ferry, a Battleship, a ferry grounding, a T-shirt, the year 1950, and a UFO sighting all have in common? If you guessed our Museum, of course, you are right. On April 25, 1950, we received one of the “Little Mo” t-shirts from a maritime collector who lived in New York. That same day, our local newspaper printed an article that told of the donation and the connections between mud, the MISSOURI, DUTCHESS, and the UFO rumors.

Thanks for reading!