If you’re reading this blog post, then, first, congratulations! You made it through 2021 or, as I’ve seen it called, 2020 part two. All joking aside, it has been a whirlwind of a year. Pandemic numbers ebbed and flowed like tides, and we all tried our best to return to some semblance of normalcy in our lives, most of us finding out that “normal” has changed.

For our part, the Museum reopened our galleries and invited you all to join us once more, to connect with the world’s waters and to each other. Our staff returned, events resumed, and our work continued. We never really closed at the onset of the pandemic. We simply switched to providing what we could to our community on virtual platforms. Now we are back in person, and Amanda and I have had a lot of photographing to do.

So, just like last year, we want to invite you to join us as we take a look back at some of our favorite photos of 2021!

Brock:

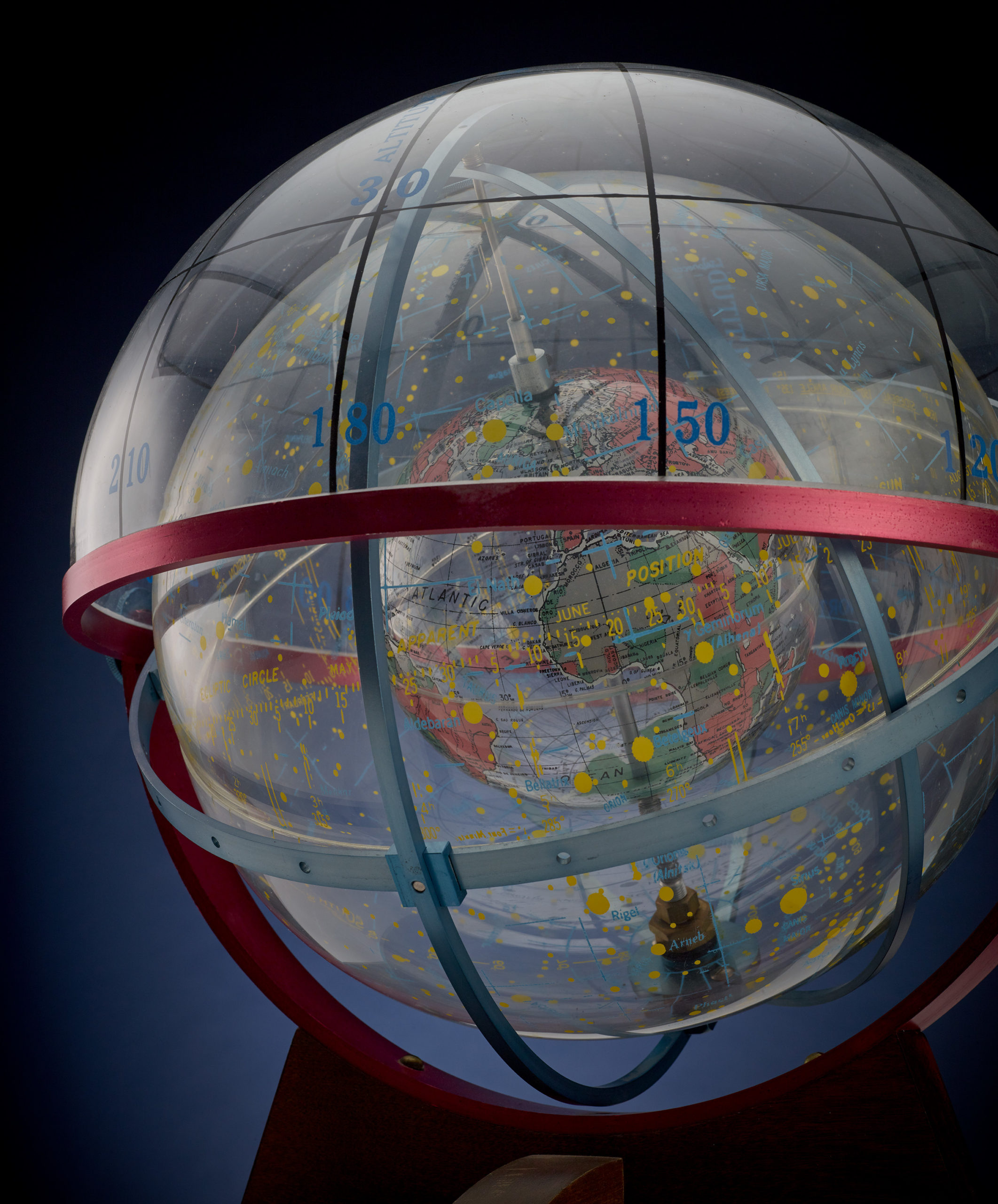

I’ll kick us off this year with a photo I consider not just one of my favorite of 2021 but likely one of the best images I’ve taken in my time at The Mariners’ Museum.

Imagine it, you’re given an artifact to photograph. It is a shiny plastic sphere inside of a shiny plastic sphere inside of a half of a shiny plastic sphere, surrounded by shiny metal. Oh, the spheres are also covered in lines, text, charts, and maps. Ok, good luck!

Am I exaggerating a bit? Yes. Am I doing it so that you’ll think I’m really cool and good at my job? Maybe. Ok, yes. But my point still stands that this was not at all an easy object to photograph. Usually, when that happens, I decide I’m just going to experiment and see what happens. That’s part of the fun of digital photography.

I set the navigation device far away from the backdrop for this image to provide a highlight that wouldn’t interfere with the object and look like the night sky. After that, I added a lot of scrims (semi-transparent fabric panels that diffuse light) above and around the artifact to prevent any hotspots or specular highlights from popping up. The result shows the shine without being uneven and provides highlights that give you a good impression of the shape of the otherwise transparent plastic spheres.

Amanda:

Hey, everyone!

2021 was a very busy and exciting year at The Mariners’ Museum and Park. Things look quite different from Brock’s and my Top Photos Blog Post last year. Nevertheless, the galleries are open and we’re making more photos to bring you more stories than ever!

So let’s get to it!

My first image is a full-circle story continued from that same Blog Post. John Cork, one of our brilliant modelmakers here at Mariners’, and a special guest named Addison, whose grandmother would bring her and her brother to the Museum. Addison took great interest in modelmaking and came back year after year.

Well, she was finally old enough to become an official junior volunteer this year! Once a week over the summer, Addison worked in the modelmaker shop with John, building her own boat model. So diligently and carefully, she worked that it seemed like she had been doing this for years. Along with John being the gentle outstanding teacher he is. Never doing the work for her; instead, explaining the steps and providing an extra set of hands to sturdy the vessel. Hopefully, she’ll be back next year and I’ll have another update for you on our volunteer modelmakers, Addison and John!

Brock:

I usually only know what I have to photograph about a week or so out. Even then, things have a habit of getting added or changing. I cannot effectively predict what I will have to photograph most of the time. This was one of those cases. We received a donation of items associated with USS Seadragon, which included this softball used to play a game of baseball when the crew reached the North Pole in August of 1960. Yes, they used a softball but played a game of baseball. Don’t @ me.

Anyway, sometimes objects with really cool stories are themselves just…not very cool. I’m sorry! An old softball is not that cool. At least not photographically. In those instances, I take it upon myself to make it more visually interesting. Yeah, it’s just a sphere of old leather, but a hard-edged monochrome background, a deep shadow, and off-center framing make it all better.

Amanda:

Next is a diptych created for our Department of Interpretation’s Black History Month programs. Our interpreters have such a breadth of knowledge. They do more than lecture and teach. They help us understand how cultural heritage affects the past, present, and future and how it’s enveloped in every object and story in our Collection. When Erika and Wisteria needed images for their programs, the thought came to me that they aren’t simply telling stories; it’s deeper than that. The stories are in them.

With this idea in mind, they needed unique photos to match. I decided to do double exposure images. It’s a technique brought over from the film era, but most digital cameras have a setting to tell the camera to expose the same image twice. First, I took a picture of them (separately) and exposed the image, so they were in silhouette. Then, we ran upstairs to the storage room to take a photo of the Collection artwork they chose for their program.

With double exposure, any part of the photo that is darker (like their silhouettes) will allow the secondary image through (the artwork). The bright, high-key areas of the initial picture will remain the same, giving the photographer a solid outline of the breakthrough image they desire…if you’ve done everything right, of course. It’s a fun technique, but it can go wrong in many ways. So I was excited when these turned out so well!

Brock:

If you’ve read literally any of my other blogs, then you’ve probably read something along the lines of “portraits are my favorite.” I talk about it constantly because it’s true. There’s something so magical about capturing an image of a person. I love the sensation I get from creating a photograph that makes the subject feel really good about themselves. We, all of us, deserve to feel like we look super hot from time to time.

In the world of photographing museum artifacts, there is an occasional overlap. In the case of maritime artifacts, that most often means photographing figureheads. This case, however, was a bronze bust of John Paul Jones. It is an inanimate object, but I got to photograph it as if Mr. Jones was a living subject sitting in front of my lens. I think the result from that overlap is a bronze bust that is strikingly alive.

Amanda:

We sometimes create our favorite images spontaneously rather than in a planned setting. For example, in July, I walked out into our main lobby, where this figurehead from HMS Edinburgh sits, to photograph another event entirely. Instantly, I saw the striated light scattered across the Scottish Sailor, created from the sun entering through the large lobby window behind it and reflecting off grates in the ceiling. I raised my camera, composed/exposed my shot, and snapped my photo. It was so unusual and picturesque. I wondered why everyone wasn’t clamoring around it, trying to get a picture like it was the Mona Lisa! But no one else seemed to notice. Never have I seen this phenomenon happen before, and I haven’t seen it since.

Brock:

I noticed this year that I became more and more enamored with photographing smaller details of objects. Our set standards for artifact photography require me to normally capture some details on objects. For example, maker’s marks or close-ups of any symbolism or text. It helps to inform researchers viewing our records about the object more thoroughly. However, these images are mainly for documentation rather than any aesthetic purpose.

Something changed this year, and I found myself thinking, “why not do detail shots just because they’re pretty, too?” So I did. Now I regularly break out the macro lens and get close to see some of the fantastic details that our objects can show us. Ship models are especially ripe for awe-inspiring levels of detail just waiting for a photograph. My favorite, though, is our navigational instruments. The rich, almost golden shine of this brass theodolite, the implied movement of the curves, the deepness of the background. Ahhh! It’s so much more than just a tool of the trade. It’s art.

Amanda:

If you know my work and style, you know I always look for ways to bring a little “flare” into my art. My final selections for the Favorite Photos of 2021 were no different. I took that technique quite literally in this image of two of our conservators cleaning our Conquering the Wild statue!

Now, taking pictures in the middle of the day while the sun is high is the worst time for photos. The sky is usually blown out, the shadows are harsh. If you get a choice, do it after sunrise or before sunset. However, when you’re an event photographer, you don’t always get the option and have to make do with your environment. So I walked around the statue while Paige and Emilie were working and started looking for ways to make the harsh light work for me. I liked the way the sun was peeking through the horse’s leg and highlighting the water cascading down from the sprayer Paige was using up on the cherry picker.

Initially, I headed out there, concerned I would let the Conservation and Marketing teams down and not get any photos worthy of use. I spent hours out there with our Conservation team and ended up with a ton of images that multiple departments have used widely since. Despite my imposter syndrome, it’s days like those I’m reminded I kind of do know what I’m doing after all!

Brock:

Glass is hard to photograph. It’s actually really fun to photograph, too. It’s weird. I guess I could just sum up everything I want to say about this one by saying that glass is weird.

Ok, ok. I’ll say more. The tricky part about photographing glass is that it is somewhat reflective and transparent, semi-transparent here because it’s amber glass. That dichotomy is what makes it so challenging to photograph. You have to get the reflections right to clearly see the shape while avoiding distracting highlights or hotspots (or being able to see the photographer in the reflection). It’s a balancing act and usually requires a good amount of fine-tuning of light positions, scrims, reflectors, etc. So if you ever photograph glass, prepare to guess, check, and revise.

I’m just going to throw in a fun fact here because I actually love glass, and I get really excited about random artifacts sometimes. This bottle was used to store bitters with very high alcohol content and sold under the guise of being “stomach medicine.” This was a regular occurrence to avoid taxes on alcohol. Later, when alcohol was banned on US naval ships sailors used them to sneak drinks aboard. Amber-colored glass is beneficial for things like medicine and alcohol because it filters all UV light and most blue light waves, which helps protect the contents from the effects of light.

Amanda:

This photo might seem familiar to you if you’re a member of the Museum. Our Cape Charles Lighthouse Lens was featured on our 2021 holiday card, and this is the image. As soon as our Advancement team told me what this year’s theme was going to be and what they had in mind, I knew exactly what I wanted to do! Have I mentioned I have a thing for a little bit of abstract?

On the day of the photoshoot, our Collections Management Specialist, Liz, controlled the spinning of the lens for me. Pausing it to line up the beams of light along the wall behind it, right where I needed them to get my shots while the light was still. Though, I wasn’t finished there. Really, I was just getting started.

As the light swung around, I propped up my camera so it (nor I) would move. Because everyone is sooooo nervous when you’re on a 12-foot ladder for some reason?!?! Like photographers don’t climb on things all the time! Haha! I took several long exposure photos until I made it look like I imagined. This particular photo was a 2.5 second exposure time specifically to give the light beams behind the lens movement while not making the lens itself too unclear.

After that, I used my mirrored reflector to get some more abstract reflection shots. Those are some of my favorites, and it was a struggle trying to decide which one to include. I wish I could post the whole set.

Recognition:

Additionally, I would like to give a HUGE shout-out to Liz, our Collections Management Specialist. She was still working as a one-woman team at the time before we brought on a new Collections member. Yet, she insisted the lens needed shine! Climbing up inside the lens, she dusted every inch of it. Then she cleaned the outside and the base until it sparkled, so the Cape Charles Lens was ready for its close-up.

Amanda:

The sun has set on 2021; however, we wanted to send you off with a little extra something this time around. So we’ve included a bonus image this year! And I swear, it has nothing to do with the fact that I’m horribly indecisive and couldn’t narrow down my list anymore. That’s not it at ALL! 🙂

Brock and I joked as we looked at these photos and can’t believe they were taken this past year. It seems like so long ago, yet somehow like no time has passed at all. We are not alone in that impression, I have no doubt. So as you reflect on 2021 and look ahead to 2022, our wish for you is to see the world in a whole new light, and we hope to continue to share the stories of connection with you at The Mariners’ Museum and Park.

Happy New Year!