Up from the Deep

The mechanical grinding of the hand-cranked winch is accompanied by sounds of effort from the watermen onboard the schooner Mattie Flavell. With every turn of the crank, the dredge reels closer and closer to the surface with their prize — oysters. It is not, however, one dredge-full that they’re working for, but many to support the popular oyster industry. The oysters will be cleaned, shucked, packed, and shipped far and wide or offered live and whole in their shells. These watermen work long hours, days, and weeks on the water harvesting the beloved bivalves. But that’s just part of the story.

For those who live on or around the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, as well as up and down the East Coast, oysters are likely a favorite and familiar sight. And though the large-scale consumption of oysters is a relatively modern thing, oysters have been harvested and eaten for thousands and thousands of years by the indigenous nations who first inhabited these lands.

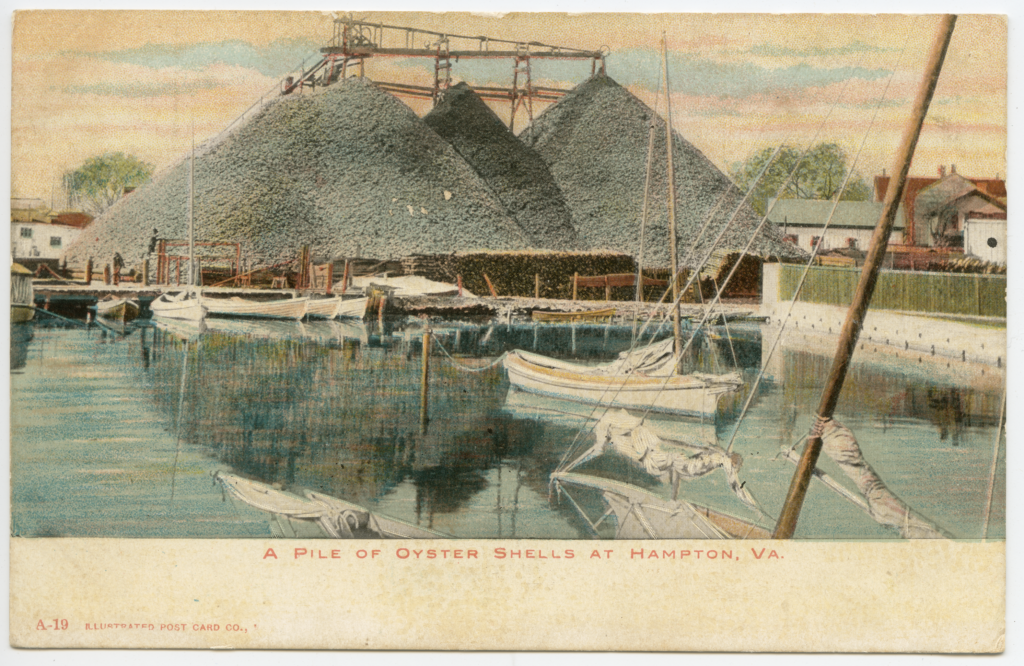

But once there were plenty — naturally formed reefs that thrived in the rivers and bays, filtering the water and contributing to healthy ecosystems. Over the centuries, with the rise of the oyster industry, many of those reefs were over-harvested, leading to a decline in the overall health of our waterways and of the oyster population as a whole.

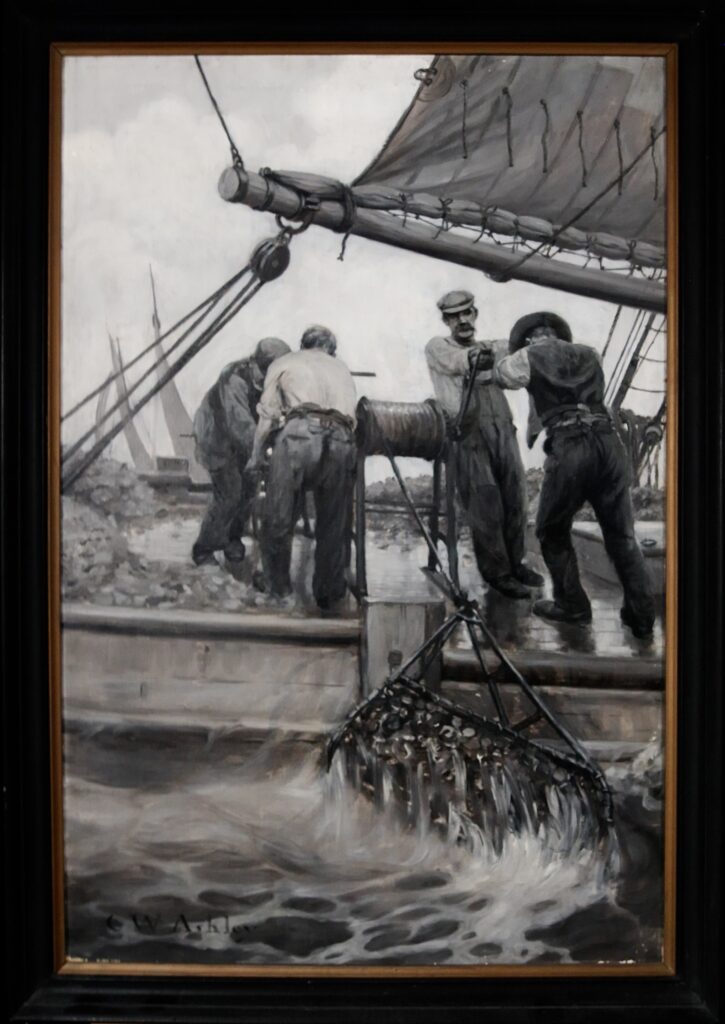

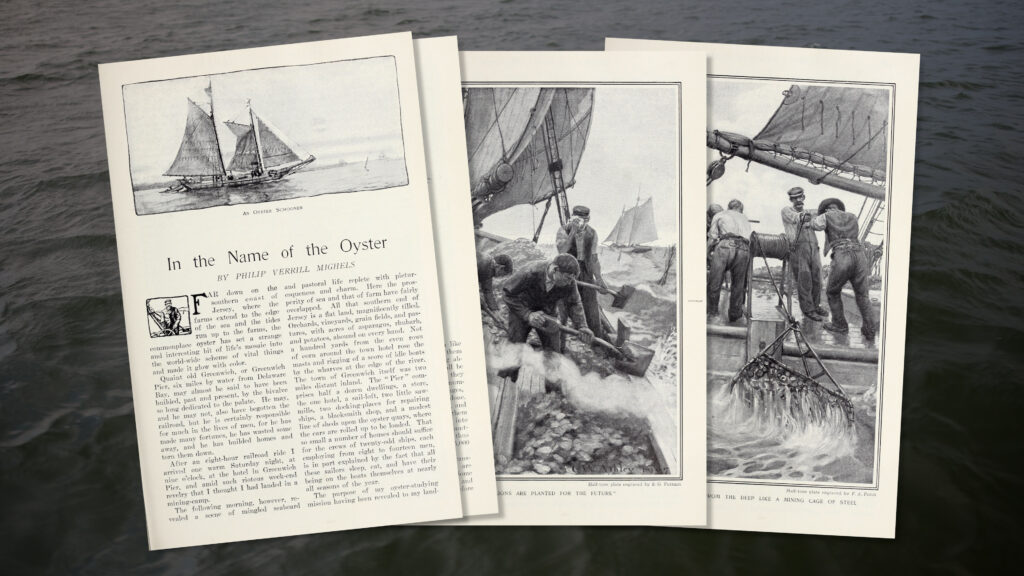

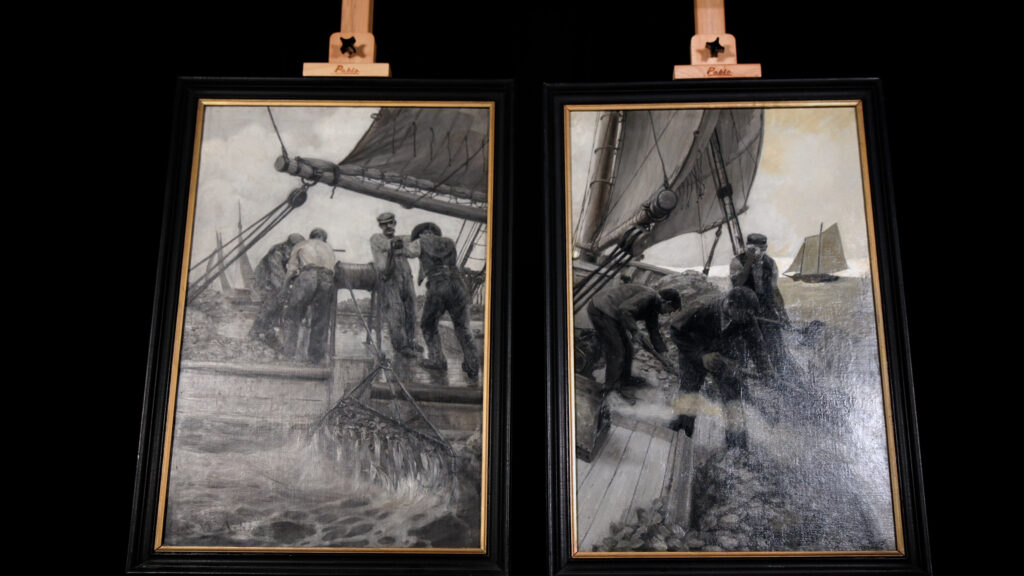

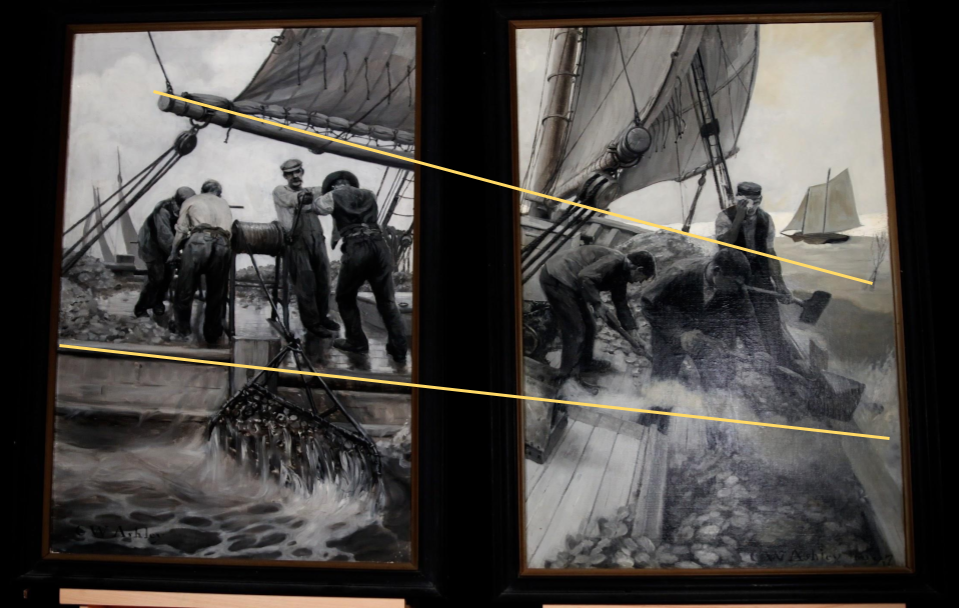

This painting titled The Dredge Comes Up from the Deep like a Mining Cage of Steel is a 1907 oil on canvas by Clifford Warren Ashley, who painted the work as an illustration for a 1908 Harper’s Monthly article titled In the Name of the Oyster.

This work’s title is ominous and, likely unintentionally, echoes the over-harvesting that was happening at that time. But I promise, this is not a bad news story.

Learning from Mariners

Over the past several months, I’ve been so lucky to work with folks like The Chesapeake Bay Foundation and Matheson Oyster Company to learn about oysters, harvesting, and aquaculture in our world today. Traditionally, oysters have been harvested through several methods, such as tonging and dredging, like we see in this painting. Often, the oyster grounds where these waterfolks worked and harvested were passed down from generation to generation, where they would care for their grounds just as a farmer would care for land-based crops. The tending and harvesting of these grounds was also passed down, creating a rich history and heritage amongst these oystering families.

More recently, though, there’s been a rise of an industry called aquaculture, where these mollusks can be cultivated with more control. I visited Matheson Oyster Company on Mobjack Bay to learn about this innovative way of growing oysters.

Aquaculture in the Mobjack Bay

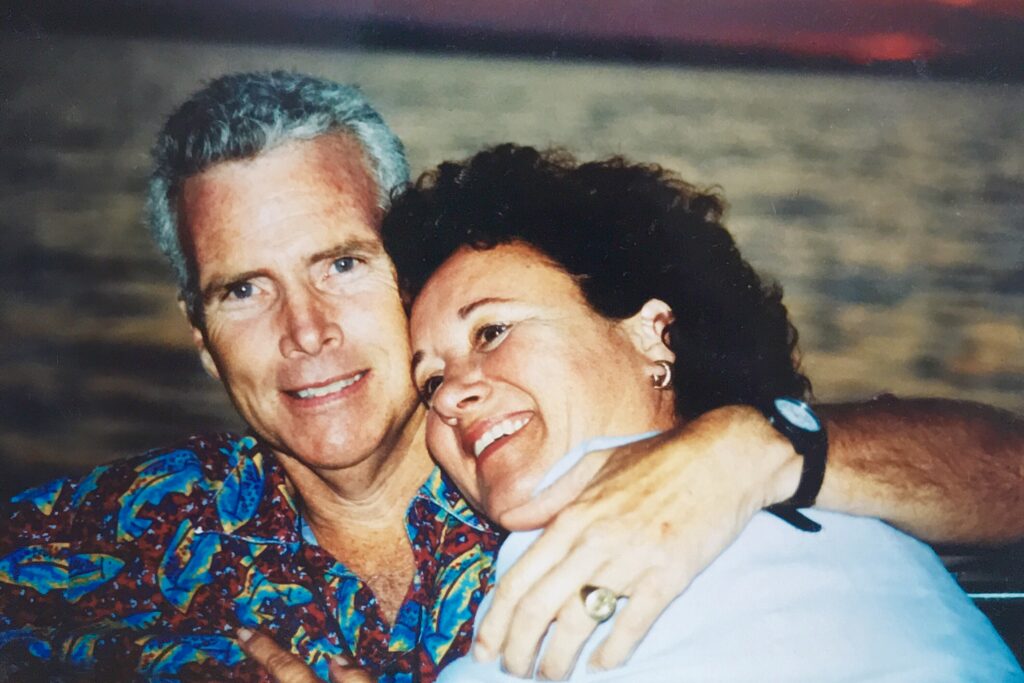

Matheson Oyster company is a family operation nestled in the marshes of the scenic Mobjack Bay. On my first visit, I spoke with Owner, Co-Founder, and Chief Marketing Officer, Sarah Matheson-Harris, and she told me about how her life and company were shaped by oysters both past and present.

Below is a transcript of Sarah Matheson-Harris, Matheson Oyster Co., Owner and Chief Marketing Officer

“I grew up, actually here in Gloucester on the water – that’s really the only reason it even came to mind is that I love Waterman culture, I just never was very involved in that myself, really, at all, other than just appreciating living on the water.

When you’re already experiencing a big life change, tackling a second one is a little bit easier to wrap your head around. Unfortunately, both of my parents ended up becoming ill at the same time. They ended up passing away a month apart from each other, and my husband and I were faced with a decision to either just not really continue much of life or community here in Gloucester, where I grew up, or we could try to figure out a way to be able to keep our foot in this community and make a very purposeful way of giving back to this community in a way that I always felt like my parents were able to. And oysters were just an obvious thing. My dad used to garden oysters as a hobby when he became retired, and it was always a thing that felt really special with us and we used to joke about it, so we just sort of decided, we were like, “What if we ended up doing this? What if we ended up creating a small oyster farm?”

Defining aquaculture in my own words, I would say it’s definitely farm-raised, intentionally grown marine life for seafood consumption. But for us, it’s farm-raised oysters. Our system is a bit different in how we grow oysters. We use an Australian long-line system. I describe it . . . it’s like an underwater vineyard. It looks like smaller, sort of cylinder-shaped baskets that sit on a wire that is bounced between PVC poles, giving it stability. It’s about a football field length-long, each line, and it utilizes the water’s natural wave action to tumble them [the oysters].

We’re channeling the natural wave action to do the work for us, whereas a lot of people are out there flipping them or bringing them in to mechanically tumble them, we’re instead looking at what’s already happening out in the environment and using that action. So, in turn, that helps create stronger shells. It grows a deeper cup, which gets it better meat content.

Our signature oyster we call “Wavelengths”, and that is a little bit of a play to our growing method. But it’s also a bit of a play on the other term of “wavelength”, that we’re very focused as a company on doing anything we do in the most environmentally friendly or sustainable fashion. And so having all these things be on that same wavelength, that was a really good reminder.

The moments that I feel the most connection are working on the educational component with consumers and getting to meet that end-consumer and showing them how oysters can be eaten, where they can be eaten, that it doesn’t have to be this big high-end hoopla, anything like that. You can have them at your home. You can have them really wherever. To us, it’s a very social thing.

Our facility is one part of a pre-existing historic working waterfront. And we recently were able to start renting the other portion of that. And that’s where a lot of the local watermen, the generational watermen, work out of. And so our goal is to be able to work with some of them to help seed some of their leases, but also, work with different higher-level nonprofit organizations to help build natural reefs, maybe even look at sea grass, different things that ultimately are working towards everything that we’re seeing happening around us, like shoreline erosion, water acidification.

Working in the oyster industry, it is very all-encompassing a lot of the things that go into it because you are working among other watermen, you see other farms out there that — obviously you’re competitive to some degree, but you ultimately all have the same goal. So we try to always support other companies, other different ways of farming as much as possible.

I would say everyone in this industry is absolutely connected because we all have the same goal in mind. And that’s putting as many oysters into the water as possible. But even on just a smaller level — a day-to-day level — we’re absolutely connected because we’re all using the same natural resources and have the same reverence and appreciation and humbling moments all together.”

A Full-Circle Story

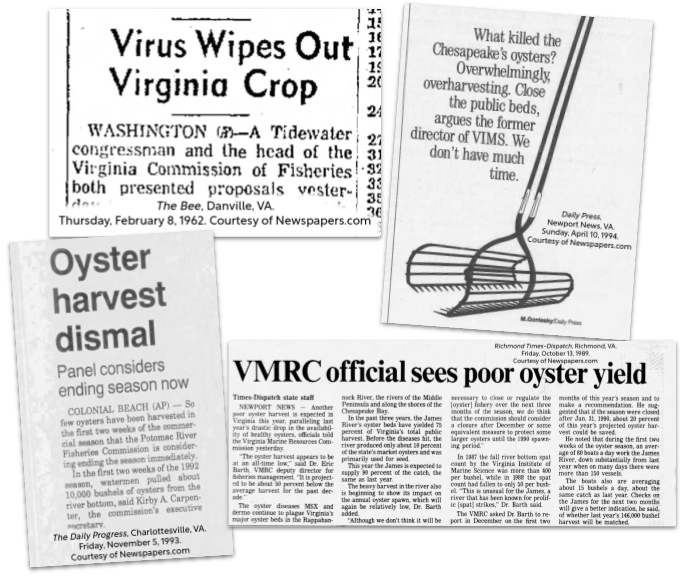

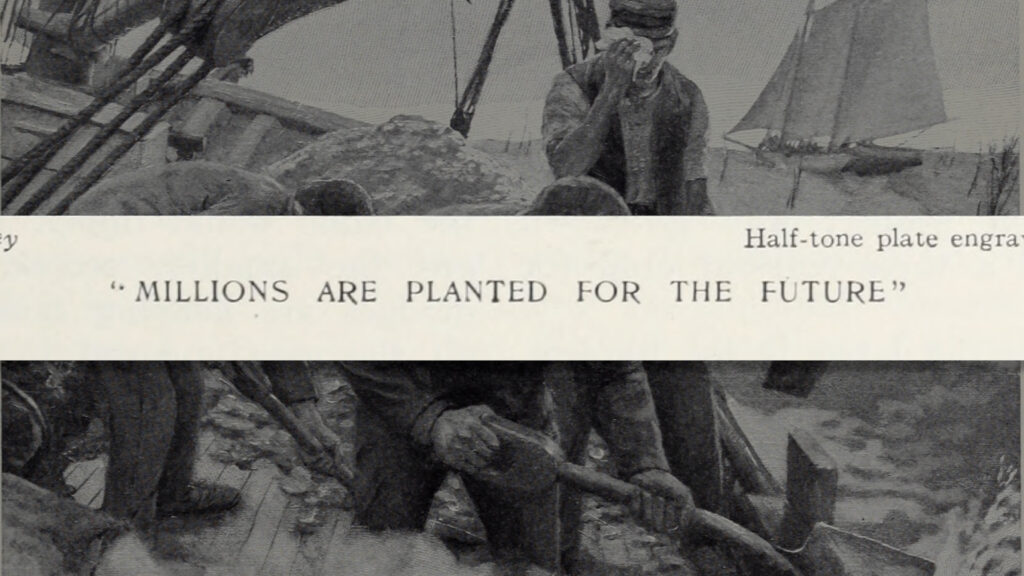

But as I mentioned, this is just one part of the story, oystering is not just about growing and harvesting, but also about looking towards the future. And this is not a new sentiment — even in 1907, as Clifford Warren Ashley was painting this commission, he made sure to capture the full-circle story of oystering. This sister painting was also created for the same article and is titled Oystering on the Mattie Flavell, but more interestingly, the caption under the image in the article reads: “Millions are planted for the Future”.

It was this caption that led me down the path of exploring the world of oysters. “Millions are planted for the Future”. In this work, we see the watermen shoveling shells overboard, replenishing their man-made reefs and oyster beds. In 1907, this was an imperfect science, but nonetheless, the concept was based in the understanding of how oysters grow. In the time I spent with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, I was able to learn about this process and better understand the importance of taking action today to ensure a better tomorrow.

Something for Everybody

Below is a transcript of Julie Leucke, Chesapeake Bay Foundation Virginia Oyster Restoration Specialist

“I have always loved biology. I grew up here in Hampton Roads and so, you know, this is my playground. Like, this was always an ecosystem I was very familiar with and in love with. Today we went and we planted some of the oysters grown through our oyster gardening program. That program enlists folks all across the state of Virginia to take home a small cage full of oysters and take care of them for about a year before returning them back to us so we can plant them onto sanctuary reefs like the one we visited today in the Lynnhaven River. These reefs are really the goal of everything we do in oyster restoration.

Oysters are broadcast spawners which means that there are male and female oysters, and they release their eggs and sperm into the water. They meet, or more likely don’t. But when they do, they create an oyster larvae. That larvae is free-swimming in the river system for about the first two weeks of its life. At that 14-day point, they actually grow a little foot and begin to look for somewhere permanent to settle down. That’s where our recycling oyster shells comes in handy. They’re looking for something hard, specifically another oyster shell to stick to and spend the rest of their lives. They are mature at a year and are able to reproduce at that point as well, and the cycle continues.

When we talk about oyster restoration, there are three main tenets that we focus on. The first is water filtration. So, oysters are filter feeders. The type of oyster used in our restoration is the eastern oyster — so, Crassostrea virginica, our native oyster — and they can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day. So, when you think about reefs that have, you know, millions of oysters on them, that’s a lot of clean water.

The second tenet we talk about is habitat value. So there are over 300 species of plants and animals that, at some point in their life cycle, make their home in an oyster reef.

And then the last reason we talk about is actually, I think, the most important, and that’s their cultural value. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation has worked closely with the Nansemond Indian Nation to do oyster restoration with them. And they’ve been working with archaeologists to really, kind of, rediscover the cultural connection that their ancestors had to oysters right here in Hampton Roads. And one of the things they’ve discovered is that their ancestors, for the past 9,000 years, have been eating our Chesapeake Bay oysters. Even more recently than 9,000 years, we have the folks that are either growing oysters or harvesting wild oysters today, often have been doing so for generations, especially the folks who are wild harvesting. And so we want to make sure that that is a livelihood that is feasible for future generations as well.

The Chesapeake Oyster Alliance, co-founded by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, is a coalition of nonprofit restoration groups like CBF, academic institutions, as well as watermen, and we have a shared goal of putting 10 billion oysters in the Bay by 2025. So we’re really capitalizing on the fact that oyster restoration has always been a partnership. It’s never just been the restoration organizations. We support each other.

Oyster restoration is so collaborative. We depend on restaurants, you know, to do our restoration work, simply. Like we could not produce our spat-on-shell — so those young oysters attached to those recycled shells — we couldn’t do that without shell from restaurants. Restaurants need oyster growers to have those oysters for us to use for restoration. It’s just all so collaborative. We couldn’t do it without them. I don’t think they could do it without us.

The oyster restoration industry is only about two or three decades old, so it’s all very new. I feel like I came into it at a really opportune time where we are just now really starting to reap all the benefits of the last two decades of restoration. So, you know, I stepped in and I’m like, “Oh, look, the water is clearer,” you know, “there’s more seahorses, there’s more black sea bass. Oyster populations are going up again for the first time in decades.” So I mostly, you know, I feel very grateful to all my predecessors who have been doing the work and not seeing the results. But I’m also really proud — being able to be out there and conducting oyster restoration, like making a difference, it’s tremendous — it’s very satisfactory.

One of the biggest reasons I love working with oysters is there’s something for everybody. So, if you care about clean water, you know, you like oysters. If you care about sportfishing, you care about oysters. If you care about oysters, you care about oysters. So there’s — there’s something for everybody.

Two Parts of the Whole

As we explored in the last episode of Beyond the Frame, each of these paintings tells its own story, but alone it is merely one part. They are meant to be seen together, something that the artist has actually shown us through the composition.

The eyelines that run through these works continue between the two pieces, tying them together. The angle of the mast on the left continues in the roll of the schooner. The stepped edge of the deck echoed in the stream of smoke that billows from an exhaust vent. In fact, it’s not until these two works are placed closely, side by side, that we see they are not just sisters but a diptych, two pieces that come together to form one.

When seen together, these works speak to the full-circle nature of sustainable oystering. A balance of harvesting and planting. Taking and giving. And in our world today, this narrative is amplified with more sides to the story, more mariners from various backgrounds working for a common goal.

This story becomes one of waterfolks working together to achieve a better future. The thing I loved the most throughout this exploration of oysters is that it is not one-sided. As an oyster travels from harvesting to consumption, then to shell recycling and reef restoration, there are so many industries and waterfolk who play an integral part of the cycle of oystering. In the past, there may have been a difference of opinions, but today there is a greater understanding that all those who come together in the name of the oyster benefit from healthy and sustainable practices. This community of waterfolk surge together, just like these paintings to ensure that — not just millions — but billions are planted for the future.

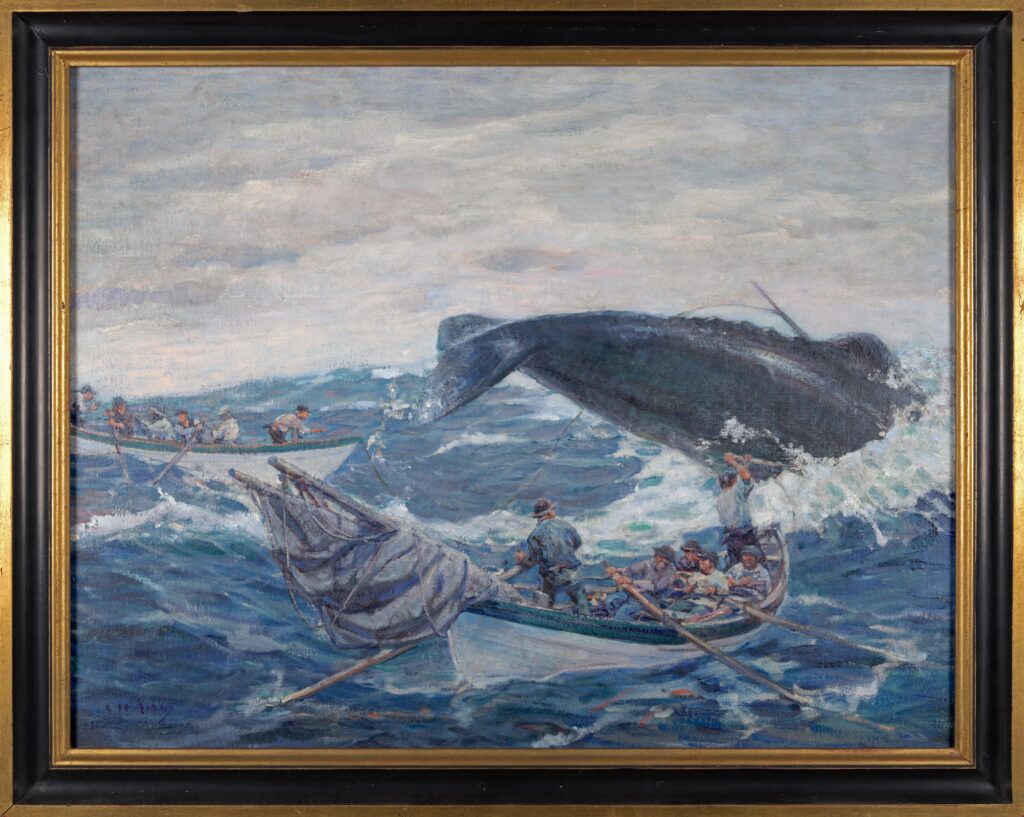

About the Artist: Clifford Warren Ashley

Clifford Warren Ashley was born on December 18, 1881, in New Bedford, MA, a town known for its whaling history. After studying art at the Eric Pape School of Art in Boston, MA and later with the landscape painter George L. Noyes, Ashley went on to continue his studies with Howard Pyle and the “Brandywine School”. Throughout his life, Ashley’s works focused heavily on maritime subjects, especially the whaling industry. In 1932, he married Sarah Scudder Clart, and the two moved to Westport, MA, where they had two daughters and remained for the rest of Ashley’s life. He is most widely known, however, for his book, The Ashley Book of Knots, which he published in 1944. Clifford Warren Ashley died on September 18, 1947.

Explore other works by Clifford Warren Ashley in The Mariners’ painting Collection:

Watch the full episode!

Sources:

- https://archive.org/details/harpersnew117various/page/684/mode/2up

- https://emuseum.delart.org/people/971/clifford-warren-ashley/objects

- https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/clifford-w-ashley-papers-5826