The American Civil War is often considered the first modern industrial war. Both North and South endeavored to mobilize their resources to wage total war. This experience revolutionized naval warfare, and in doing so, forever changed America’s political, social, and economic fabric.

Proponents of seapower had witnessed significant changes in ordnance, motive power, and ship design during the first half of the 19th century. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory was the first to recognize that a new class of vessels, hitherto unknown in naval service, was needed. Mallory knew the possession of an armored ship was a matter of first necessity. The question then begged an answer: How could the agrarian South create such a warship? [1]

Mallory’s first answer was found in the ashes of Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Virginia, ruined and abandoned by the Federals on April 20, 1861. Amidst the yard’s ashes, the Confederacy found a way to start building an ironclad navy. The partially burned steam screw frigate USS Merrimack was raised and placed in the undamaged dry dock. The frigate’s conversion into an ironclad was underway by June 1861. [2]

Union Awakes

News of the Confederate efforts to convert Merrimack into an ironclad began to leak northward throughout the summer of 1861. The Union Secretary of the Navy already knew that the US Navy was outdated and needed an effective shipbuilding program to stop the all-important Confederate cotton for cannon trade. Accordingly, Welles realized that the Union had to construct armorclad vessels capable of countering any ironclad the South might produce or purchase. [3]

The Ironclad Board

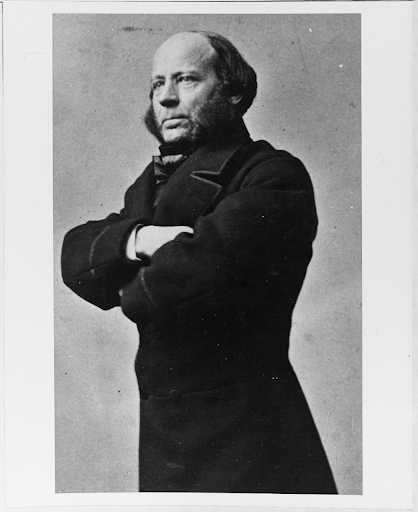

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 305.

The Secretary of the Navy advised Congress that “much attention has been given within the last few years to the subject of floating batteries, or steamers.” Based on Welles’s recommendation, Congress appropriated $1.5 million to construct armored warships. Congress also authorized the appointment of an Ironclad Board to review designs. The Board consisted of Flag Officer Joseph Smith, Flag Officer Hiram Paulding, and Captain Charles Henry Davis. Bids were solicited on August 7, 1861. Once received, they surveyed 16 designs, including one made of rubber. Two designs were quickly selected: a European-styled broadside ironclad and the iron clapboard corvette Galena. While the Galena design was approved, Captain Davis questioned the vessel’s stability. Cornelius Bushell, who had made a fortune in shipping and railroads, was advised to meet Naval Engineer John Ericsson to understand more about his proposed ironclad. Ericsson explained to Bushnell that Galena was seaworthy; however, the Swedish-American engineer showed the financier a model of his tower battery, which would eventually be known as USS Monitor. [4]

The Monitor was indeed a unique shot-proof design, and it could be built quickly. When Monitor became the first ironclad commissioned, it was thrust into battle on March 9, 1862. It stopped CSS Virginia‘s (Merrimack) destruction of the rest of the wooden Federal fleet in Hampton Roads. Ericsson’s Monitor became the toast of the country as the “little ship that saved the nation.”

The Mariners’ Museum MS0555-02-001-02.01

USS Roanoke Transformation

The Battle of Hampton Roads proved that more ironclads were needed to achieve victory. Noting how the Confederates had transformed the steam screw frigate USS Merrimack into an ironclad, US naval leadership thought its sister ship, USS Roanoke, could also be converted into an ironclad. If the Confederates could do it, so could the US Navy. This ironclad was the first warship to mount three turrets on the centerline. Called a ‘monitor’ due to its turrets, the vessel was really a heavily armored hybrid warship. The Passaic-class turrets gave Roanoke a wide arc of fire, limiting the number of guns required for a broadside. Even though the ship’s guns were muzzleloaders, they were the best armament a vessel of the 1860s could mount. The 150-pounder Parrott rifle gave great range and accuracy to the ship’s battery, and the XV-inch Dahlgrens could destroy any Confederate ironclad afloat. The ship’s freeboard differed from all other monitors; however, it was still inadequate for service at sea.

Roanoke was an attempt to produce an oceangoing ironclad; yet, the re-use of the poorly supported wooden frame was unable to effectively carry the weight of the armor, turrets, and guns. The ironclad was top heavy and rolled badly, making it an unsuitable gun platform. If the vessel had been built of iron with a well-supported frame, the ironclad could have been a match for many of the experimental ironclads constructed during the 1860s and 1870s. Instead, Roanoke was a dismal failure, destined for the scrap yard not long after the end of the Civil War.[5]

More Ironclads

The US Navy then gave Ericsson several additional contracts to build improved monitors and ‘monitor fever’ raged in shipyards throughout the North. Likewise, the original Monitor and its subsequent iterations were unseaworthy, lacked adequate firepower, were poorly ventilated, and had limited speed. More monitors were made during the war than any other ironclad design despite these problems. Yet, other new ironclad designs were built and served with the US Navy during the war.

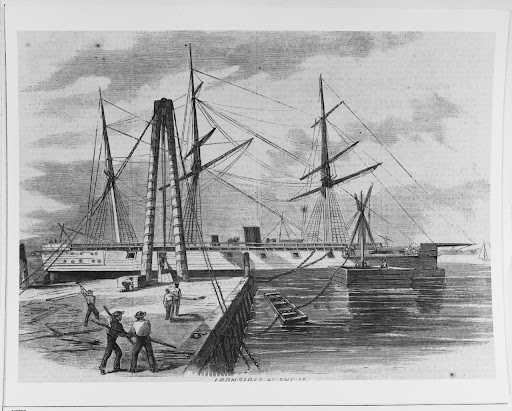

The first of the three ironclads approved by the Ironclad Board to have its keel laid was what was to be known as USS Galena. Cornelius Scranton Bushnell was a good prewar friend of Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. Bushnell was determined to help preserve the Union, at a profit if he could. The businessman had been advised he would receive a contract to construct the Unadilla-class gunboat Owasco if he built it at Charles Mallory & Sons Shipyard in Mystic, Connecticut. Bushnell made those arrangements. Word got out that the Union would soon organize an Ironclad Board to select ironclad warships. Cornelius Bushnell received advanced notice of this selection process and was asked by the Navy Department to submit a proposal in June, [6]

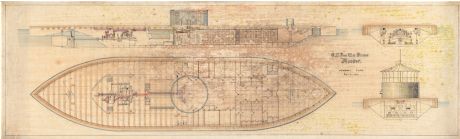

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 59305.

Favoritism in Naval Contractors

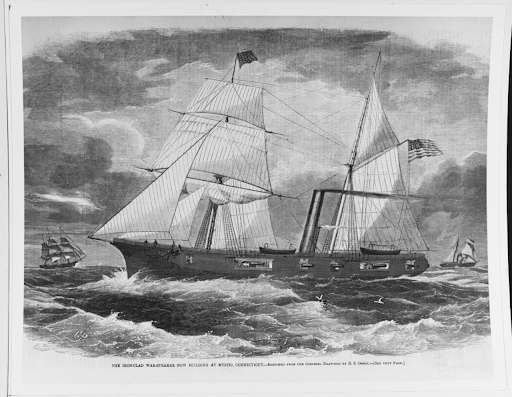

unknown. Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 56579.

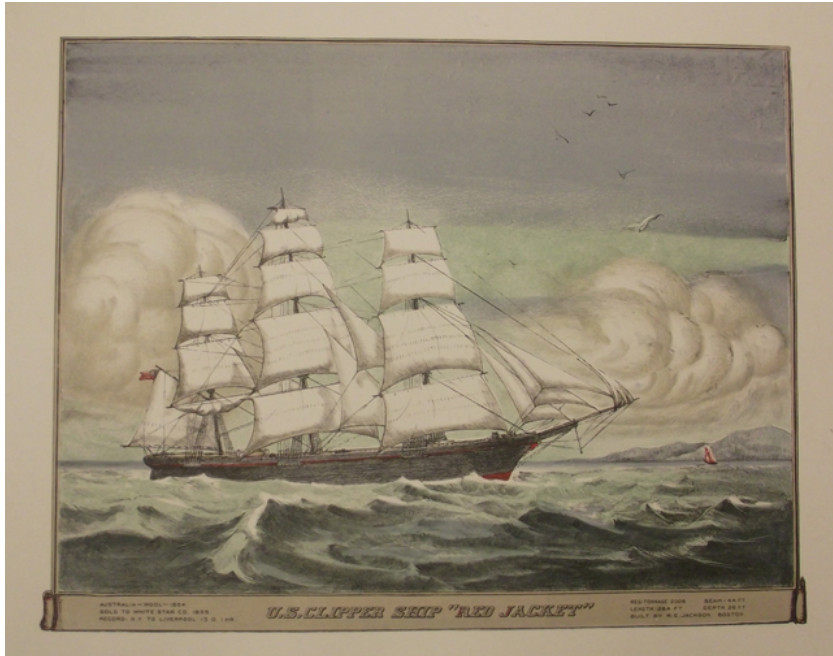

Bushnell wanted this contract, and he was greatly aided in securing it due to his prewar friendship with William Seward and Gideon Welles. This early warning prompted Bushnell to contact naval architect Samuel Hartt Pook in early June to create an ironclad design. Bushnell already knew S.H. Pook had already produced drawings for all Unadilla-class 90-day gunboats, including Bushnell’s Owasco. Pook was already very famous for his designs of clipper ships like Witchcraft, Northern Light, and Red Jacket. The Red Jacket was the holder of the speed record for the New York City-Liverpool run and the Liverpool-Melbourne routes. Pook’s work on the Unadilla-class was directed by John Lenthall, Chief of US Navy Bureau of Construction, Equipment and Repair based on the 1860 re-build by Naval Constructor S. M. Pook of USS Pocahontas. The second class screw sloop was re-configured at Gosport Navy Yard. Pook’s further shipbuilding pedigree was that his father, Samuel Moore Pook, was a naval constructor at the Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston. The senior Pook became famous for designing the City-class ironclads built by James Eads. This successful class was known as “Pook’Turtles.”[7]

As S. H. Pook designed the proposed ironclad Galena, Bushnell worked with the Navy Department to obtain funding. Pook finished the design on June 28, 1861. A bill to appropriate $1.5 million for the construction of Ironclads was introduced in the Senate on July 19. One day later, Bushnell contracted Maxon, Fish & Co. of Mystic, Connecticut, to build the ironclad. On July 22, 1861, the keel was laid. [8]

USS Galena Design

USS Galena was designed initially as a wooden-hulled schooner-rigged corvette with three masts. The initial main armor plan was to have the ship’s sides protected by 2.5-inch wrought iron plates backed by 1.5 inches of india rubber and supported by 18-inch thick wood backing. While under construction, the plan was modified under the direction of S.H. Pook and Flag Officer Joseph Smith, Chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks. Both were concerned that Galena could not support the weight of all the iron. So, the ship was lengthened, and a new armor scheme was developed. The rubber backing was removed and replaced by three-quarter inches of iron plate. In other places, the armor was reduced. Two inches of iron plate were used above the gunports, and the bow and stern were protected by half-inch iron, and the deck received half-inch iron over two-and-a-half inches of wood. What was unique about Galena was its tumblehome design with the side armor consisting of interlocking iron rails.

USS Galena Characteristics

Tonnage: 950 tons

Length: 210 ft.

Beam: 36 ft.

Draft: 12.8 ft.

Machinery: I screw, 2-cylinder Ericsson vibrating-lever engine, 2 boilers

Speed: 8 knots

Armament: two 100-pounder Parrott rifles, one 30-pounder Parrott rifle, and four IX-inch Dahlgren Shell guns

Compliment: 150 [9]

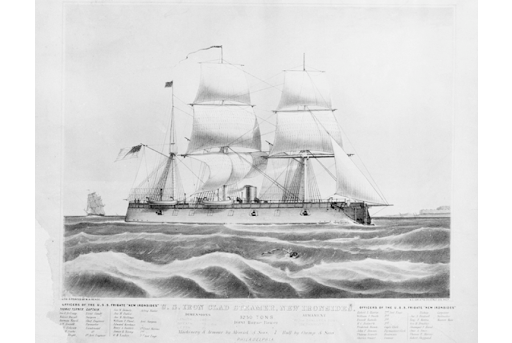

The More Traditional Design

The third warship selected by the Ironclad Board was USS New Ironsides, a similar design of the French ironclad Gloire. This Bark-rigged warship was constructed based on lessons learned during the Crimean War. When launched on November 28, 1859, Gloire was the first ocean-going armored warship. [10]

Engraver unknown. Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command

# NH 58741.

In Honor of USS Constitution

USS New Ironsides was named in honor of USS Constitution. One of the first six original fast frigates built for the US Navy, Constitution earned its nickname “Old Ironsides” when the ship defeated and captured HMS Guerriere on August 19, 1812. The British frigate was severely shot up and dismantled; however, Constitution serviced the engagement with minimal damage. Many of the British cannonballs appeared to bounce off Constitution’s 21-inch-thick pine and southern live oak. This prompted an American sailor to exclaim, “Huzzah! Her sides are made of iron!” which gave Constitution its nickname. [11]

Building New Ironsides

The Ironclad Board selected the firm of Merrick & Sons of Philadelphia to design and construct New Ironsides at the cost of $780,000. The company primarily built engines and did not have a slipway. Consequently, Merrick subcontracted the armorclad’s construction to William Cramp & Sons Iron Shipbuilding and Engineering Company. Cramp claimed credit for the detailed design of the armorclad’s hull; however, most of the design work was completed by Merrick. [12.]

Several aspects of New Ironsides were unique. To lessen the armorclad’s draft, the ship had a wide beam and a flat bottom. A two-piece articulated rudder proved to be unsatisfactory. When the ship’s speed increased, it became unmanageable. The wooden hull was coppered, and the propeller could be disengaged while operating under sail only. The Bark-rigged ironclad had three masts for long-distance voyages. The masts and rigging would eventually be removed once in station and replaced with smaller signaling poles. [13]

Problems Everywhere

Several problems arose during the initial construction and maiden voyage. Merrick & Sons was paid an additional $34,322.06 for modifications, resulting in the addition of gunports and a pilothouse. The pilothouse was situated aft of the smokestack. Not only was it very small and could not fit three men, its view forward was blocked by the funnel. Under certain conditions, fumes clouded the pilothouse and nearly asphyxiated everyone in the conning tower. [14.]

USS New Ironsides was to mount sixteen IX-inch Dahlgren shell guns. These were not powerful enough to penetrate the typical Confederate ironclad’s two layers of two-inch iron plate. Consequently, the US Navy insisted that the primary battery be twelve XI-inch Dahlgrens and two 150-pounder Parrott rifles. The new battery plan made New Ironsides a far more powerful warship. Nevertheless, it did result in a major problem as the gun deck was too small to manage the existing wooden carriage and new carriages had to be designed. Two clamps (compressors) were fitted to squeeze the rails, increasing the friction between the rails and carriage. This configuration was not strong enough to handle the recoil. Additional clamps and rope breeching were added, yet, nothing worked satisfactorily until December 1862, when strips of ashwood were placed beneath the compressors to give the system friction. Another modification was the addition of two 4-inch iron shutters meant to protect every gunport. [15]

New Ironsides Armor

This ironclad had a waterline belt of 4.5 inches-thick wrought iron that was reduced to three inches three feet below the waterline. The gun deck was protected by 4.5-inch iron belt; however, both the stern and bow were unprotected. It was recognized that this did not give adequate protection to the battery. So, a bulkhead of 2.5 inches of iron backed by 12 inches of white oak. The side armor was also backed by 12 inches of white oak. The plating was installed just like it was on Gloire: the plates were mounted with countersink screws; the armor plates were cut with a groove at the end, and an iron bar was placed between the grooves to strengthen the armor belt. [16]

USS New Ironsides Characteristics

Tonnage: 4,120 tons

Length: 232 ft.

Beam: 57.6 ft.

Draft: 15.8 ft.

Machinery: 1 screw, 2-cylinder horizontal direct-acting engine by Merrick, 4 boilers

Speed: 6 knots

Armament: two 150-pounder Parrott rifles, two 50-pounder Dahlgren rifles, fourteen XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns, one 12-pounder rifle, and one 12-pounder smoothbore

Armor: 3 to 5 in. armor belt, 1 in.deck,10 in pilothouse

Compliment: 460 officers and men [17]

On To Hampton Roads

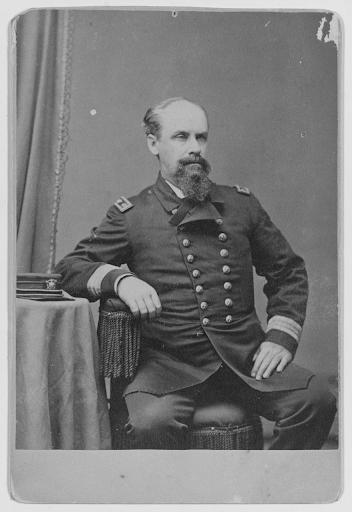

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 44.

USS New Ironsides was commissioned on August 21, 1862, commanded by Commodore Thomas Turner. The ironclad arrived in Hampton Roads a few days later; however, New Ironsides was detailed to Philadelphia Navy Yard for repairs. The casemate ironclad had proven to have inadequate speed and difficulty steering. These issues were never remedied. [18]

Stephens Battery

Fears of war with Great Britain over the American-Canadian border in 1841 prompted President John Tyler and Secretary Of the Navy Abel P. Upshur to secure $8.5 million from Congress to expand the US Navy. This situation prompted Robert L. Stevens and Edwin A. Stevens of Hoboken, New Jersey, to propose to Congress that they would build a shot-proof steam armorclad warship. Congress approved this concept and authorized $250,000 for the “construction of a shot-and-shell proof steamer, to be built principally of iron, on the Stephens’ plan.” Known as the ‘Stephens Battery Act,’ this was the first government sponsorship of the construction of an iron warship and occurred a full 17 years before the commissioning of the French ocean-going ironclad Gloire. [19]

Development of the Battery

The Stevens family built a drydock on their property across the Hudson River from Manhattan. The keel was laid for what was supposed to be a 250-foot-long ship with a 40-foot beam. A unique feature was that the six shell guns proposed for the gun deck were loaded from below from armored casemates. Stevens Battery was protected by 4.5 inches of sloped iron backed by 14 inches of locust timber. The battery was a semi-submersible able to lower itself in the water to better protect it from shell fire. The ship was to have a speed of 18 knots. [20]

Redesign

Because of the development of heavier shell and rifled guns, the Stevens brothers decided to redesign the armorclad in 1854, despite many Navy Department officials wishing to scrap the project. So, the brothers invested their own money in the project and increased the ironclad’s dimensions. The armor was increased to 6.75 inches, and the ship was lengthened to 420 feet. It was planned to mount seven guns, each with a steam-powered ramrod to reload the guns. The 1854 design included eight steam engines with twin screws capable of making an estimated 20 knots. [21]

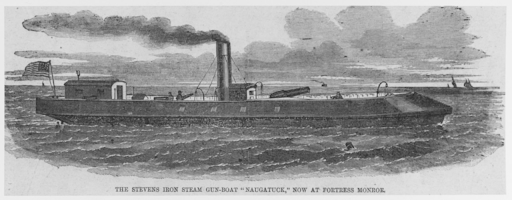

Rejected

More than $728,435 had been spent on Stevens Battery by 1861, and the armorclad was still in drydock. Edwin and his brother John C. Stevens offered to complete the vessel; however, the US Navy was not interested. Since the Stevens brothers believed their ship would help the Union win the war, they purchased a smaller iron-hulled vessel, named Naugatuck initially, to prove their concepts. The ship was modified into a smaller prototype of the larger ironclad. This ship was again rejected by the US Navy; nevertheless, it was commissioned into the United States Revenue Cutter Service as E.A. Stevens in 1862 and then loaned to the US Navy. [22]

USRCS E.A. Stevens Characteristics

E.A. Stevens was considered a semisubmersible armored gunboat and was the third version of the original Stevens Battery concept.

Tonnage: 192 tons

Length: 110 ft.

Beam: 20.6 ft.

Draft: 7.8 (ballast empty), 9.10 (ballast full)

Machinery: twin screws

Armament: one 100-pounder Parrott rifle, two 12-pounder Howitzer

Speed: 18 knots

Compliment: 24 officers and crew [23]

Virginia Cometh

In early April 1862, the USRCS E.A. Stevens arrived in Hampton Roads to join USS Monitor. Both ships soon became involved in the third foray into Hampton Roads on April 11, 1862. Monitor stayed in the channel between forts Monroe and Wool, while E.A. Stevens (often called Naugatuck) had a more forward position. Virginia steamed back and forth in Hampton Roads to bait Monitor into battle. The Federals hoped the Confederate ironclad would move into the Chesapeake Bay where Virginia could be attacked by Union rams like the Vanderbilt. While the slowdown continued for several hours, CSS Jamestown captured three merchant vessels. Then, Virginia, now captained by Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall, returned to the Elizabeth River and fired several shells at E A. Stevens. The Union ironclad fired one shot in reply. All shots missed, and the excitement of this action was to be considered anything but daring or dangerous and was over as the tide receded. [24 ]

Galena Comes to Hampton Roads

photographers. Date unknown. Courtesy of Library of Congress # 2017895409.

USS Galena was commissioned on April 21, 1862, under Commander Alfred Taylor. The commissioning was significant as Cornelius Bushnell had wished that the ironclad would be named Retribution. The name Galena was used in honor of Major General US Grant’s capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. Galena, Illinois, was Grant’s hometown. Nevertheless, as soon as Galena arrived in Hampton Roads on April 24, 1862, Commander John Rodgers was immediately named the ironclad’s captain. Rodgers and Flag Officer L.M. Goldsborough, commander of the North Atlantic Squadron, inspected Galena the next day. Both agreed that the iron corvette might not be totally shot-proof, yet, they implemented improvements to make the armorclad more battle-ready. All the masts and rigging were removed, and the nuts were covered with sheet iron to prevent them from breaking loose when shot hit the ironclad. [25]

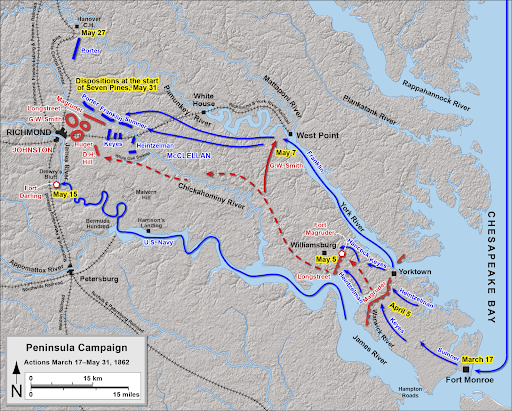

President Lincoln Comes to Norfolk

By May 1, 1862, time was running out for the Confederates in Hampton Roads. When Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston abandoned the Warwick-Yorktown Defensive line, Norfolk became isolated, and CSS Virginia’s future was in danger. President Abraham Lincoln arrived on April 6, 1862, and with Major General John Elliswool helped organize an attack on Norfolk to destroy the Confederate Ironclad. Simultaneously, Lincoln convinced Louis Goldsborough to send a strike force into the James River led by John Rodgers of USS Galena. [26]

Action at Last

On May 8, 1862, twin naval forces attempted to strike at the Sewell’s Point Batteries defending the Elizabeth River and Fort Boykin on Burwell’s Bay and Fort Huger on Maiden’s Bluff, guarding the lower James River. USS Monitor and USRCS E.A. Stevens Battery, supported by USS Susquehanna, San Jacinto, and Dacotah, began shelling Confederate positions. CSS Virginia steamed out of the Elizabeth River to contest the Union advance. Tattnall was faced with the need to protect the James River to defend Norfolk. He hoped to draw USS Monitor into another duel; however, the Union warships retreated to an anchorage. Accordingly, there would not be a second duel between Monitor and Virginia in Hampton Roads. [27]

Meanwhile, Galena and its supporting gunboats silenced the two forts and, by May 9, 1862, reached Jamestown Island, finding the fort there abandoned. As Rodgers’ squadron moved up the James River, General Wool had captured Norfolk, resulting in the destruction of Virginia. [28]

On to Richmond

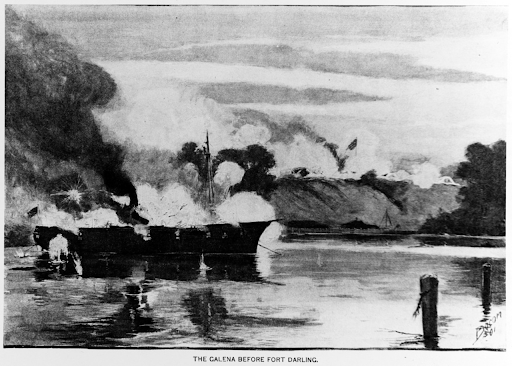

Goldsborough was prompted to send a naval strike force to capture Richmond. Rodgers returned to the lower James River and shelled forts Boykin and Huger once again. There Rodgers expanded the strength of his James River Flotilla with the addition of Monitor and Naugatuck. Now the Federals had three ironclads steaming toward Richmond. Unfortunately, the Federal flotilla’s progress up the river was slowed by groundings and the need to stop and investigate every abandoned Confederate fort and riverside community. These delays enabled the Confederates to fortify Drewry’s Bluff, just eight miles below Richmond. Drewry’s Bluff rose 90 feet above the James River and was armed with seven heavy guns. Three hundred yards in front of Fort Darling (the name of the fortification atop Drewry’s Bluff) were several stone-laden barges and the wreck of CSS Jamestown. By the evening of May 4, 1862, Rodgers’ ships had reached new Cornelius Creek and awaited the battle that was sure to come on the morrow. [29]

To Prove Yourself as Ironclad

By 6:45 a.m. on May 15, 1862, Rodgers’ flotilla got underway and by 7:45 a.m. had reached to within 600 yards from the bluff. The river was very narrow at this point, yet, Rodgers placed his ship into position with “neatness and precision.” The battle commenced immediately, and the engagement did not go well for the Federals. By 9:00 a.m., Confederate plunging shot began to take its toll on Galena. The Monitor endeavored to position itself to take more of the brunt of the shot coming from Drewry’s Bluff. It could not elevate its guns adequately and, after three hits, dropped back downriver. Lieutenant John Constable of USRCS E.A. Stevens Battery (also referred to as the Naugatuck) semi-submerged his ironclad and was not struck by Confederate shot. Nevertheless, after 17 rounds fired, its 100-pounder Parrott burst, and this unusual ironclad played no further role in the battle. [30]

In the meantime, Galena was taking a pounding. Of the 43 shots that had struck the ironclad, 13 penetrated the corvette’s armor cladding. Its railings were shot away, the smokestack riddled, and there were 24 casualties. USS Galena’s interior, according to Acting Assistant Paymaster William Keeler of USS Monitor, “looked like a slaughter house … of human beings … the decks were covered with large parts of half coagulated blood and strewn with portions of skull, fragments of shells, arms, legs, hands, pieces of flesh and iron, splinters of wood and broken weapons were mixed in one confused, horrible mess.” [31]

unknown. Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 53984.

Lessons Learned

The Battle Of Drewry’s Bluff disproved many notions about ironclads. USS Monitor was rather shot-proof. However, it lacked effective fire control and firepower. Despite these flaws, the US Navy continued to order more monitors. E.A. Stevens (Naugatuck or Stevens Battery) did not prove satisfactory and was returned to the USRCS. This vessel continued to serve the Treasury Department until late 1862. The original Stevens Battery was left in Hoboken and was eventually acquired by the State of New Jersey. Major General George McClellan was given the task of making the ship viable. There was not enough money to spend on this 25-year-old project, and it was never finished. An attempt was made to sell it to Prussia. When that failed, Stevens Battery was broken up and sold for scrap. [32] The world was just not ready for a semi-submersible ironclad!

Cornelius Bushnell’s ironclad proved to be a complete failure as it was not shot proof against plunging fire. Nevertheless, a new purpose had been found as Galena’s iron was removed, and the warship was converted into an unarmored screw sloop of war with a three-masted rig. USS Galena was assigned to the West Gulf Blockading Squadron and fought during the August 5, 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay. [33]

To Port Royal Sound

While discussions were going on about what should be the best ironclad, USS New Ironsides detailed to service with the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. The ironclad arrived on January 17, 1863, and underwent minor modifications, including replacing its masts with signal poles. Eventually, New Ironsides would become Flag Officer Samuel Francis DuPont’s flagship during the planned Charlestown operation. [34]

Ironclads are Coming

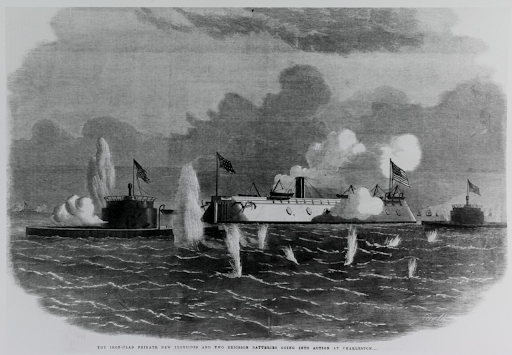

Gideon Welles wrote to DuPont on January 6, 1863, that the “ironclads have been ordered to and are now on their way to join your command to enable you to enter the harbor of Charleston and demand the surrender of all its defenses or suffer the consequences of a refusal.” [36] Seven of the new Passaic-class monitors – Weehawken, Passaic, Montauk, Patapsco, Nahant, Catskill, and Nahant – were used in the attack on Charleston. Besides the broadside ironclad New Ironsides, another ironclad was added to the strike force: the tower (Citadel) ironclad USS Keokuk.

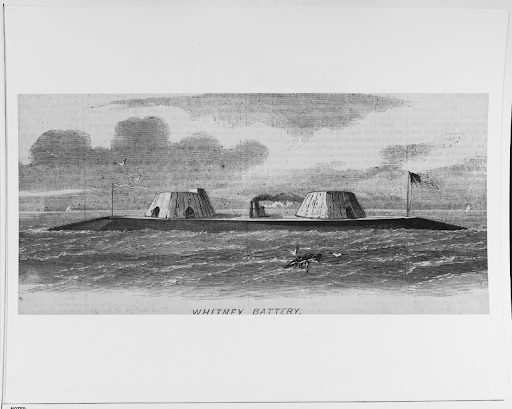

Enter USS Keokuk

All of the success accorded to the first monitors, ship designer Charles W. Whitney, a former partner of John Ericsson, to develop a radically different experimental ironclad. Whitney’s Keokuk was one of the first warships constructed entirely using iron. Originally named Moodna, the Keokuk was named for a city in Iowa. The ironclad was built at J.S. Underhill Shipbuilders, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, New York, and was launched on December 6, 1862.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 58748.

Design Concepts

Besides total iron construction, this ironclad used wood only for deck planks and filler in its armor. The hull featured an experimental armor scheme with a “sandwich” of 1-inch iron plates enclosing a 2-inch inner layer of wood bolted together and placed to a thin wooden framework. This wood and iron was then covered by a half-inch (some sources say 1-inch or ¾ inch) of boilerplate. The two stationary conical towers looked like twin turrets but were not. The towers had three gunports each and contained one XI-inch Dahlgren. The guns were placed on a shortened wooden carriage pivot mount. USS Keokuk’s towers were also composite, being made from 1-inch thick by 4-inch deep horizontal iron bars alternating with yellow pine planks of the same dimension, then sheathed with layers of overlapping flash-bolted half-inch rolled iron plates. The total tower armor was 5.75 inches. The Keokuk had a wooden deck made of 5-inch planks overlaid with half-inch iron plate. The ironclad’s bow and stern were flooding spaces to enable raising and lowering its waterline. [37]

USS Keokuk Characteristics

Tonnage: 677 tons

Length: 159.6 ft.

Beam: 36 ft.

Draft: 9.3 ft.

Machinery: 2 screws, one 4-cylinder direct-acting condensing engine with three boilers

Speed: 9 knots

Armament: two XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns

Compliment: 92 [38]

DuPont’s Attack on Charleston

Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont’s long-awaited ironclad assault on Charleston Harbor began at noon on April 4, 1863. Nine ironclads formed the attack force in a line ahead column. The lead ship was Weehawken, commanded by Captain John Rodgers. When Rodgers reached to within 500 yards of Fort Sumter, he abruptly stopped his ironclad as he noticed a line of barrels that he believed were torpedoes. This maneuver forced the line behind Weehawken into disarray. Communications between the ships broke down as the other ironclads endeavored to hold themselves in position. [39]

Passiac-Class Monitors

Seven Passaic-class monitors fought on April 7, 1863, and most of them were severely damaged. The Weehawken was hit 43 times in forty minutes. A torpedo exploded near the ironclad, which lifted the monitor out of the water but caused no damage. Shot from Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie had great effect on each of the ironclads. Weehawken began taking water through a shot hole in its decks. USS Passaic was struck 35 times; its XI-inch Dahlgren was disabled, and its turret malfunctioned. USS Patapsco took 47 hits. It was followed by USS Catskill, which was hit by 20 shots that broke the deck plates and forward deck planking, causing it to take on water. Captain John Worden in Montauk had difficulty maintaining his ship’s position; it was hit 14 times. USS Nantucket was struck by 51 shots, and its turret was jammed. Nahant moved to within 600 yards of Fort Sumter and was battered by 36 shots. One struck Nahant’s pilothouse killing the helmsman and wounding the pilot. Nuts were sheared off of iron bolts. The ironclad’s steering gear was damaged, and three other shots disabled its turret. [40]

USS New Ironsides in Action

Admiral DuPont’s flagship was USS New Ironsides, and this broadside ironclad did not play a significant role in the battle. A massive ironclad, it was in a narrow channel and could not correctly maneuver. The flagship had to anchor several times to avoid running aground. At one point in the battle, New Ironsides anchored over a 3,000-lb gunpowder torpedo; yet, it failed to explode. The warship only fired one broadside during the entire action. Even though New Ironsides was struck by 50 shots, it suffered no significant damage or casualties. [41]

Smyth, engraver, ca. 1863. Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command

# NH 85573-KN.

Another Failed Ironclad

The newest ironclad to join DuPont’s fleet was USS Keokuk. Near the end of the engagement, it took a position 600 yards away from Fort Sumter. The Confederates focused their cannonade upon this ironclad. It was struck 90 times in half an hour. This under-armed and poorly armored warship was holed beneath its waterline by almost 20 projectiles and was in a sinking condition when it withdrew from action. The ironclad sank the next day. [42]

After Action Report

DuPont’s attack on Charleston was a dismal failure. Passaic-class monitors were unable to maintain an effective rate of fire to challenge the Confederates’ fixed fortifications. The heavy ordnance, including smoothbores and Brooke rifles, proved to be a match for the stationary monitors. The Confederates had placed range markers in the harbor, which enhanced their aim. Most of the 439 shots from the forts struck their targets. The monitors were not totally shot-proof from plunging Confederate shot, the turrets were easily jammed, and pilothouses were prominent targets.

DuPont believed that Charleston could only be taken with Army assistance. The Admiral thought that had he renewed the attack on the next day, part of his ironclad fleet would have been lost. Major General David Hunter advised Admiral DuPont, “No Country can ever fail that has men capable of facing what your ironclads had yesterday to endure.” [43]

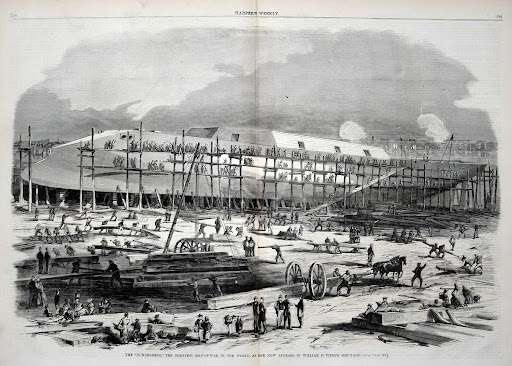

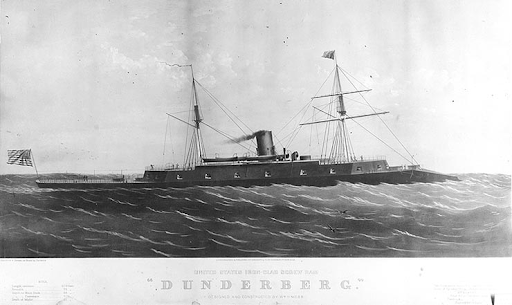

Even More Ironclads

William H. Webb Shipyard of New York produced a version of an ocean-going ironclad known as Dunderberg (meaning thundering mountain in Swedish). Although started in 1862, it was not completed until after the war. This frigate was designed by John Lenthall as a reproduction of CSS Virginia, except with sails, utilizing sloping casemate sides and a 50-foot ram. With a length of 377 feet and four inches, Dunderberg was the longest wooden-hulled warship built in the United States. The ship was plated with four and a half inches of iron on its casemate and three and a half inches elsewhere. This ironclad had a double bottom and collision bulkheads. Dunderberg was designed to mount four XV-inch Dahlgrens and eight XI-inch Dahlgrens. The ironclad was never accepted by the US Navy and was sold to France as Rochambeau. [44]

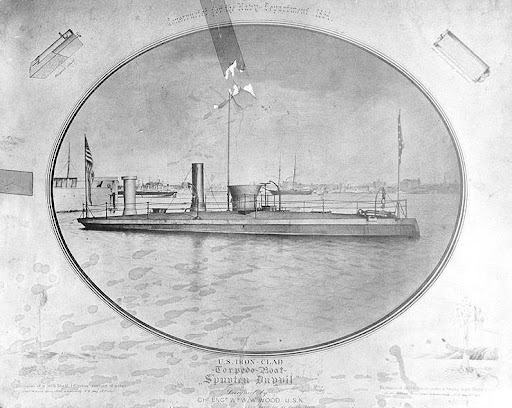

Spyuten Duyvil

Also known as Stromboli, Spuyten Duyvil was designed by S.H. Pook and built by William W.W. Wood Shipyard in Fairhaven, Connecticut. The vessel was wooden with a low freeboard and flush deck. The iron spar torpedo boat had a funnel and conning tower. It was plated with five inches of iron on sides, three inches on deck, and five inches on the pilothouse. Spuyten Duyvil had a retractable spar torpedo; however, it was too slow and unwieldy for effective service. This torpedo boat did serve in the James River and fought at the engagement at Trent’s Reach on January 24, 1865. It was kept as an experimental vessel until scrapped in 1880.

Spyuten Duyvil Characteristics

Tonnage: 207 tons

Length: 84.2 ft.

Beam: 20.8 ft.

Draft: 7.5 ft.

Machinery: 1 screw, 1 HP Engine

Speed: 5 knots

Armament: one spa torpedo

Compliment: 23 [45]

USS New Ironsides in Charleston

Following the failed ironclad attack on Charleston, USS New Ironsides remained with the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron continuing to bombard Confederate defenses in an effort to capture Fort Wagner on Morris Island. The New Ironsides maintained its station off Morris Island from July 11 to September 6, 1863. The ironclad survived a torpedo boat attack on August 21, 1863.

In September 1864, New Ironsides participated in two major actions within Charlestown Harbor. When USS Weehawken grounded between Cummings Point and Fort Sumter, the casemate ironclad steamed to within 1,200 yards of Fort Moultrie and sent 483 shells into the fort. Even though New Ironsides was struck about 70 times and incurred no severe damage, the ironclad was able to force the Confederate gunners into their bombproofs. The next evening crewmen from New Ironsides would participate in a boat attack to capture Fort Sumter. The assault was poorly planned and was repulsed with severe casualties. [46]

CSS David’s Attack

USS New Ironsides was at anchor on the evening of October 5, 1863, when a semi-submersible torpedo boat CSS David, commanded by Lieutenant William T.G. Glassell. As the Confederates approached to within 50 feet of the giant ironclad when the Union crew saw David. Glassell replied with a blast from his shotgun and then rammed New Ironsides with its spar torpedo. This detonated under the ironclad’s starboard quarter. USS New Ironsides only received minor damage and suffered one killed and two wounded. [47]

Repairs and Reassignment

The ironclad remained in station until early June when it was detailed to Port Royal Sound for minor repairs. This work included replacing the masts and rigging. The ironclad was then sent to the Philadelphia Navy Yard for a complete overall, arriving there on June 24, 1864, and recommissioned in late August 1864. Commodore William Radcliff had been accepted into the US Navy as a midshipman on March 1, 1825. He served with distinction during the Second Seminole War and the Mexican War. In 1861, he was questioned by the Secretary of the Navy as to his loyalty to the Union; nevertheless, he was a native of Virginia. He eventually was in command of USS Cumberland. Radcliff was not aboard the ship when the sloop of war was sunk by CSS Virginia on March 9, 1862.

When New Ironside’s refit was completed, Captain William Radford took his ship to Hampton Roads, Virginia. The ironclad was now part of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron and would participate in the two attacks on Fort Fisher defending Wilmington, North Carolina. Radford commanded the ironclad division during these assaults. USS New Ironsides played a major role in shelving this Confederate fortification until Fort Fisher surrendered.

The second attack on Fort Fisher witnessed eight crew members receiving the Medal Of Honor after the battle. One of these men was Signal Quarter Master Thomas English, the highest-ranking African American enlisted man in the US Navy. [48]

A Fiery End

After brief service in the James River, the war ended, and New Ironsides was decommissioned and placed in ordinary at League Island, Philadelphia. The ironclad was destroyed by fire during the night of December 16, 1865. [49]

What Was the Best Union Ironclad?

The Battle of Hampton Roads on March 8-9, 1862, set off “monitor fever” throughout the North. Of the 84 ironclads built or laid down for the Federal fleet, 64 were turreted monitors. This unique style had proven that it could defeat Confederate casemate ironclads thanks to the addition of XV-inch Dahlgrens into their turrets. Otherwise, monitors lacked firepower, were uncomfortable to work within and were unseaworthy. Three of the alternatives to monitors – USS Galena, USS Keokuk, and USRC Naugatuck – were failures.

Nevertheless, the most durable and effective Union ironclad during the Civil War was USS New Ironsides. While it could only make 7 knots (just like a monitor), New Ironsides was far superior to the monitor design in its seaworthiness, armor, and armament. The ship’s heavy broadside and superior solid iron plate made it the only US ironclad that could stand up against most European ironclads. The Confederate ironclad Stonewall may have been a difficult opponent for USS New Ironsides if that Confederate ship could have deployed its ram. Nevertheless, New Ironsides’ heavy ordnance should have won the day.

Endnotes

1 John V. Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, Charleston, SC: History Press, 2007, 58.

- IBID., 60.

- IBID.

- John V. Quarstein, The Monitor Boys, Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011, 27-29.

- Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, 237.

- Jeff Remling, “Patterns of Procurement and Politics: Building Ships in the Civil War,” The Northern Mariner, Canadian Research Society, Vol. XVII (1), January 2008, 27-29.

- Bern Anderson, By Sea And By River: The Naval History Of The Civil War, New York: Knopf, 1962, 41-2, 82, Howard P. Nash Jr., A Naval History Of The Civil War, New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1972, 28 and 82.

- Remling, 21-24.

- Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies 1855-1883, Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 2001, 11.

- Spencer C. Tucker, Handbook of 19th Century Naval Warfare, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000, 66-67.

- Ian W. Toll, Six Frigates: The Epic History Of The Founders Of The Us Navy, New York: W.W. Norton, 2006, 350.

- Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, 130.

- William C. Emerson, “USS NEW IRONSIDES: America’s First Broadside Ironclad,” Robert Gardiner, ed., Warship, London: Conway Maritime Press, 1993, 624-628.

- William M. Roberts, USS New Ironsides In The Civil War, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1999, 39-41.

- IBID., 25, 33-37, 121, and 123.

- IBID., 23.

- Silverstone, 11.

18, Roberts, 29.

- Tucker, 63-64.

- Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, 51-52.

- IBID., 52.

- Spencer, 62.

- Silverstone, 10-11.

- Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, 120-121.

- Donald L. Canny, The Old Steam Navy: Ironclads, 1842-1885, Annapolis, MD.: 1993, 21-22.

- Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, 128.

- Quarstein, The Monitor Boys, 117-119.

- Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, 124-128.

- Quarstein, The Monitor Boys, 124-128.

- Ed Bearss, River Of Lost Opportunity: The Civil War On The James River, 1861-1862, Lynchburg, VA: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1995, 63-64.

- Quarstein, The Monitor Boys, 134.

- Silverstone, 11.

- IBID.

- Roberts, 39-41.

- IBID.

- Official Records of the Union And Confederate Navies Of The War Of The Rebellion, Ser.1, Vol. 13, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1912, 371.

- Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, 166.

- Silverstone, 12.

- Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, 165-166.

- IBID.

- IBID.

- IBID.

- IBID., 166-167.

- Silverstone, 11-12.

- IBID., 42.

- Roberts, 72-78.

- IBID., 81-91.

- IBID., 92-106.

- IBID., 127-128.