Samuel Chapman Armstrong: A Biographical Study,

New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, p. 254.

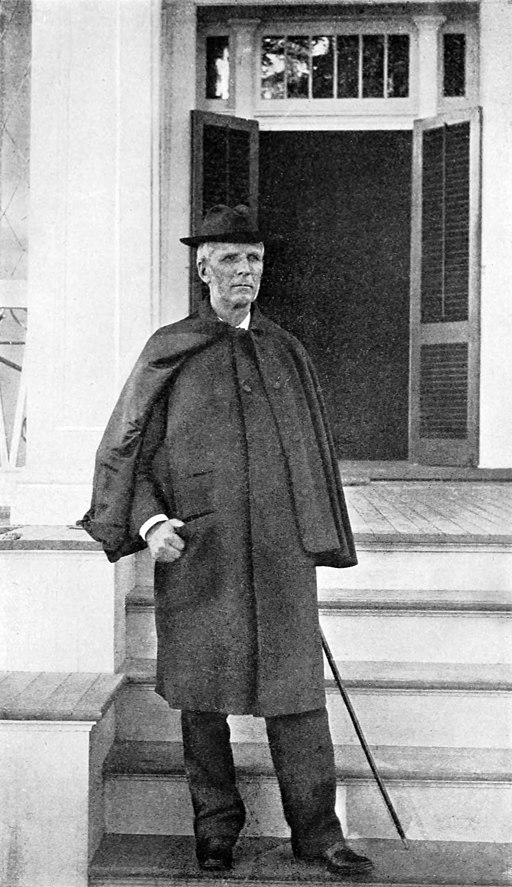

Samuel Chapman Armstrong was the founder of Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University). A native of Hawaii, he fought with the Union army during the Civil War. Eventually, Armstrong was brevetted brigadier general. After working for the Freedmen’s Bureau, he recognized that African Americans needed greater educational opportunities, which prompted him to establish Hampton Institute. Among its most noted graduates are Booker T. Washington and Thomas Calhoun Walker.

His Younger Years

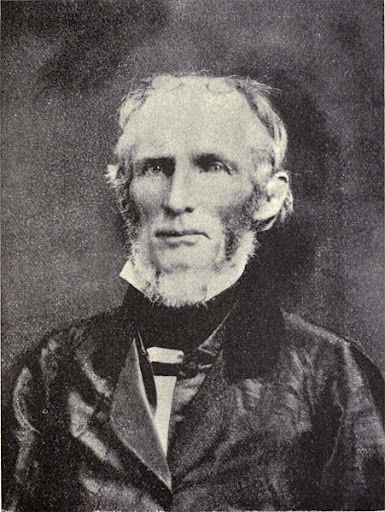

Portraits of American Protestant Missionaries to Hawaii, Honolulu 1901: Hawaiian Gazette Company, p. 35.

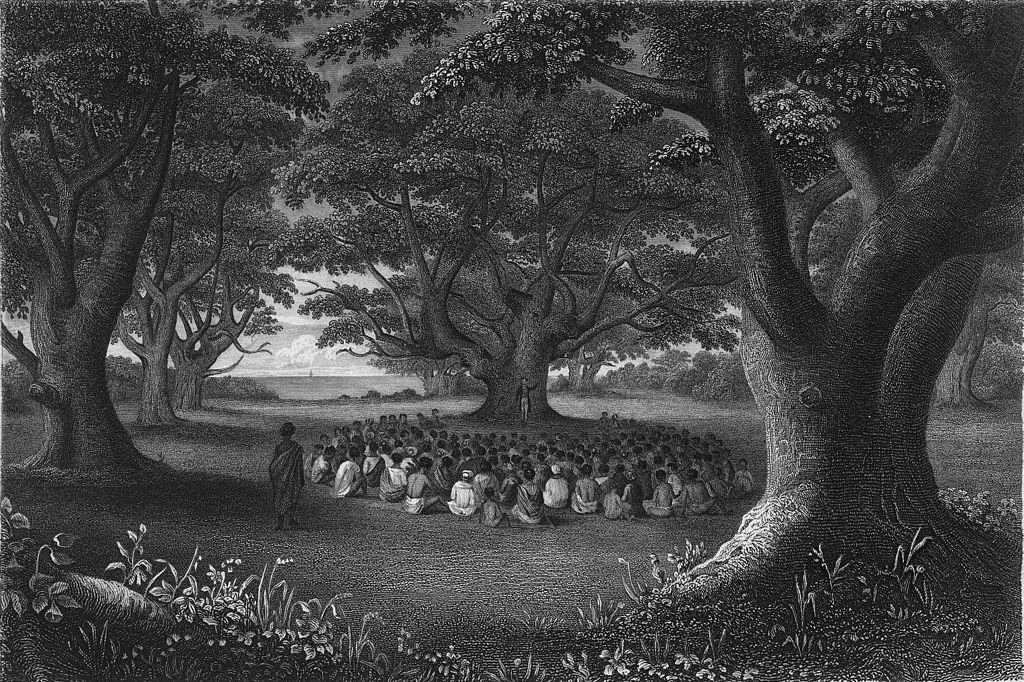

Armstrong was born on January 30, 1839, on the island of Maui in the kingdom of Hawaii. His parents, Richard and Clarissa Chapman Armstrong, were Protestant missionaries sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. The Armstrongs arrived in 1832 and began establishing churches. In 1840 Richard Armstrong was appointed Kahus (Senior Pastor) of Kawaiaha’o Church in Honolulu. The church was made of coral and served as the national church of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Armstrong also served on the kingdom’s privy council and the House of Nobles. King Kamehameha III appointed Armstrong as Minister of Public Instruction in 1847, and, in 1855, he became President of the Board of Education. The educational model he established taught students faith-based citizenship. His teaching activities made him known as “the father of American education in Hawaii.”

Alfred T. Agate, artist. Courtesy of the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Samuel Chapman Armstrong was born on January 30, 1839. He attended Punahou School and then its collegiate branch, Oahu College. Although very studious, he was also a noted prankster. The young Armstrong secretly lowered the flag of the American consulate in Honolulu in honor of a family pet’s death and hanged his sister’s dolls to halt their “i-doll-try.”

Education

During his teenage years, Samuel worked as his father’s secretary. This gave him an understanding of the principle of students completing manual labor to support their education. Armstrong’s methods enabled the students to acquire valuable skills by farming or practicing crafts like carpentry. Samuel would keep these important lessons with him for the rest of his life. Sadly, the senior Armstrong died due to a horseback riding accident on September 23, 1860. Samuel would then attend Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, based on his father’s wishes. He lodged with and obtained special lessons from the college president Mark Hopkins. This taught him the importance of a practical, useful education that taught students how to make a living and be good Christians. James Garfield, later a major general and president of the United States, graduated in 1862 with Samuel Armstrong. Garfield later defined the ideal college as “Mark Hopkins on one end of a log and a student on the other.” As soon as Garfield and Armstrong matriculated, they joined the US Army.

In the Army Now

founder of Hampton Institute, ca. 1860-1870. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Initially, the Civil War meant nothing to Samuel Chapman Armstrong as he identified himself as a Hawaiian. His parents were anti-slavery; however, he had had only minor interactions with African Americans. He wrote that the war should not end until “every slave…can call himself his own, and his wife and children his own.” He joined the 125th New York Infantry as a captain, having recruited a company of men from Troy, New York. His unit was captured at Harper’s Ferry on September 15, and was exchanged in December 1862 and returned to the 125th. As part of the 3rd Division of I Corps under General Alexander Hays, Armstrong fought during the battle of Gettysburg. On July 3, 1863, he helped defend Cemetery Ridge against Pickett’s Charge.

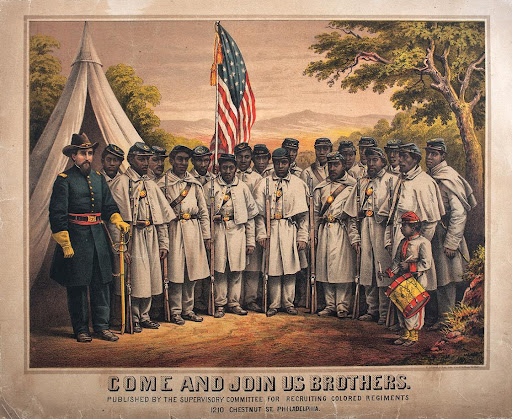

US Colored Troops

Armstrong sought to serve with the newly formed United States Colored Troops. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and assigned as executive officer of the 9th USCT. While training at Camp Stanton near Benedict, Maryland, Armstrong established a school to educate his troops. Due to pre-war slave codes, most of his men could not read or write. Lt. Col. Armstrong believed that literacy would make better soldiers.

Armstrong was reassigned to command the 8th USCT. He led this unit during the siege of Petersburg and engaged in the fierce battles of Deep Bottom and Fussell’s Mill. In November 1864, Armstrong was promoted to colonel “for gallant and meritorious service.” His troops were the first to enter Petersburg on April 3, 1865. Armstrong noted that the 8th USCT received “a most cheering and hearty welcome from the colored inhabitants of the city, whom their presence had made free.” His unit was involved in the Appomattox Campaign and was sent to Ringgold Barracks near Rio Grande City, Texas. On October 10, 1865, the 8th USCT began marching from Texas to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where Armstrong and his men were mustered out of service on November 10, 1865. As a result of his outstanding war service, on January 13, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Armstrong as a brevet brigadier general of volunteers to date from March 13, 1865. The US Senate confirmed his new commission on March 12, 1866.

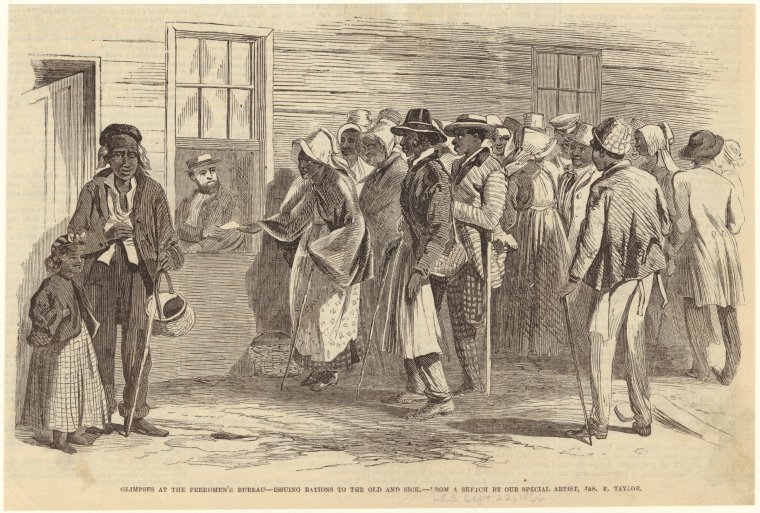

Freedmen’s Bureau

From 1866 to 1868, Armstrong served as assistant sub-commissioner of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Land (the Freedmen’s Bureau) for the district covering the lower Virginia Peninsula and Surry, Isle of Wight, and Northampton counties. He strove to reduce the huge population of homeless refugees by pressing formerly enslaved people to accept employment as farm laborers. Accordingly, many Blacks felt that Armstrong and his bureau associates sympathized more with the defeated white landowners than with the newly freed African Americans they were charged with aiding. Armstrong was himself deeply committed to assisting the Black population, but he also believed in the superiority of the white race. He sought to train the freed people so that they might better compete within the constraints of their circumstances.

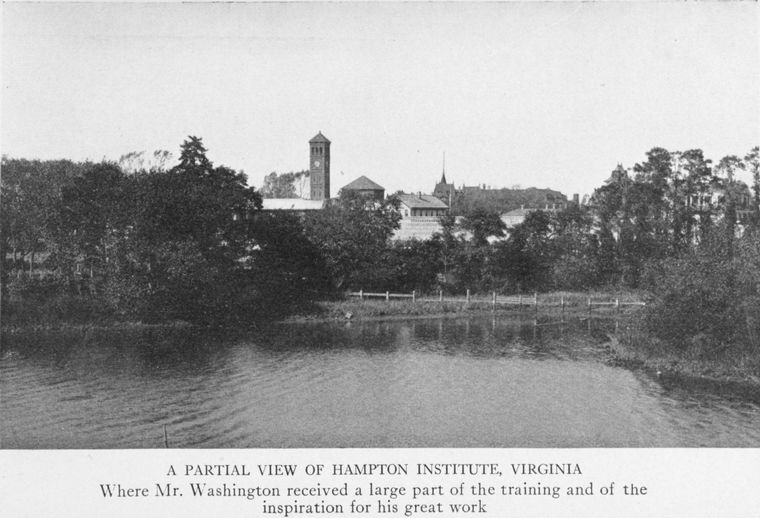

Hampton Institute

In April 1868, Armstrong decided to create an educational institution to train Black teachers who, in turn, would teach other African Americans. It was not to be just an ordinary school. General Armstrong incorporated much of the education he had gained from his father and Mark Hopkins of Williams College, yet he also included his ideas. Armstrong firmly believed that the future development of African Americans depended on the strength of their families. Therefore, Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute was coeducational so that partners could be educated together.

Armstrong strongly believed in the need for racial uplift via schools like Hampton Institute. This school reflected the paternalistic attitudes of whites who felt it was their duty to develop those they regarded as lesser races. Gen. Armstrong molded the curriculum to reflect his background as an abolitionist and as a child of white missionaries in Hawaii. Armstrong believed that several centuries of slavery in the United States left many of its Black citizens in an inferior moral state, needing help to be more active in American society. “The solution lay in a Hampton-styled education, an education that combined cultural uplift with moral and manual training.” Armstrong believed in “an education that encompassed the head, the heart, and the hands.” Therefore, the primary means to advance Blacks within society was by the moral power of literacy and labor.

Hampton Institute emphasized students take courses in English, arithmetic, geography, basic science, and history. In addition, all students were required to work in the school’s shops or on the school farm. While some argued that Armstrong’s methods reinforced the theory that Blacks were only suited for manual labor, his initial design was simply practical, Hampton had no endowment, and most of its initial students were impoverished. Manual labor in the school’s fields and shops subsidized their education. Furthermore, most graduates were expected to go into teaching and needed a supplemental income to support themselves and their families. Approximately 84% of the first 723 graduates of Hampton’s first twenty classes became teachers, while others sought to expand their education, becoming doctors, lawyers, ministers, and politicians.

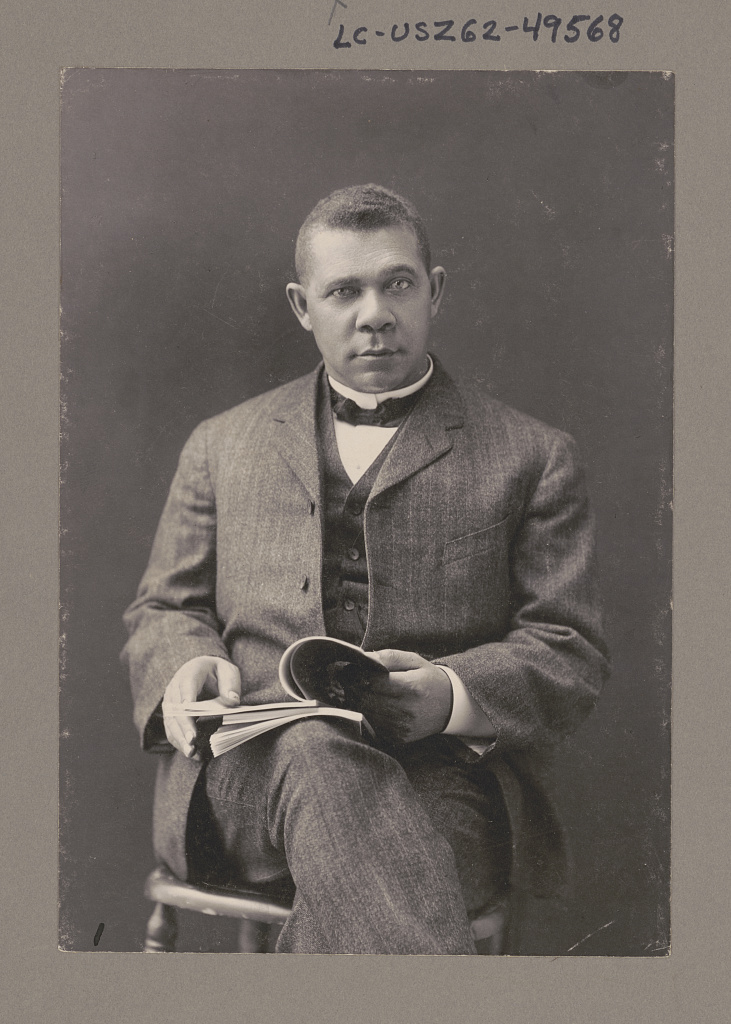

The Most Distinguished Early Graduate

Perhaps one of the leading lights of the Hampton-styled education was Booker T. Washington. Washington described Armstrong as “the most perfect specimen of a man, physically, mentally, and spiritually, the most Christ-like.” Despite his appearance after walking for weeks from West Virginia, Washington was admitted to the school because he demonstrated his ability while sweeping and dusting a room.

Washington became a major advocate of the Hampton-styled educational system. After graduation, he attended Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C. He then returned to Hampton to teach. In 1881, he was given the opportunity to establish a normal school in Alabama known today as Tuskegee University. Washington was often criticized for advocating a philosophy of accommodation to racial segregation. Yet, the Hampton model proved to be a great success at Tuskegee.

Booker T. Washington’s most significant impression upon leaving Hampton was Brigadier General Samuel Chapman Armstrong. He considered the general “the noblest, rarest human being that it has ever been my privilege to meet….One might have removed from Hampton all the buildings, classrooms, teachers, and industries, and the men and woman still there the opportunity into daily contact with General Armstrong and then alone would have been a liberal education.”

More Notables

James Apostle Fields was a former enslaved person and contraband. He was among the first graduates of Hampton Institute, later receiving his law degree from Howard University. He served two terms in the Virginia General Assembly. Then he became a school superintendent. He also farmed and maintained his law practice. When Fields died, his home became the first African American hospital on the lower Virginia Peninsula.

Another famous graduate was Thomas Calhoun Walker. Born into slavery in 1862, he sought to attend Hampton Institute. Despite having limited verbal skills, Armstrong allowed him to work during the day and attend classes at night. After graduation, Walker read law under former enslaver and Confederate general William Booth Taliaferro. Walker passed the Virginia Bar in 1887 and worked tirelessly to defend fellow African Americans from unjust arrests. He entered politics, and in 1891, Walker was elected to the Gloucester County Board of Supervisors. In 1896, President William McKinley appointed T. C. Walker as Virginia’s first Black Collector of Customs. In 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt named him as advisor and consultant of Negro Affairs for the Virginia Emergency Relief Administration. This appointment earned him the nickname the “Black Governor of Virginia.” Walker was an educator at heart. He became the superintendent of Gloucester County Negro Schools and built numerous schools for African American students throughout eastern Virginia.

Legacy

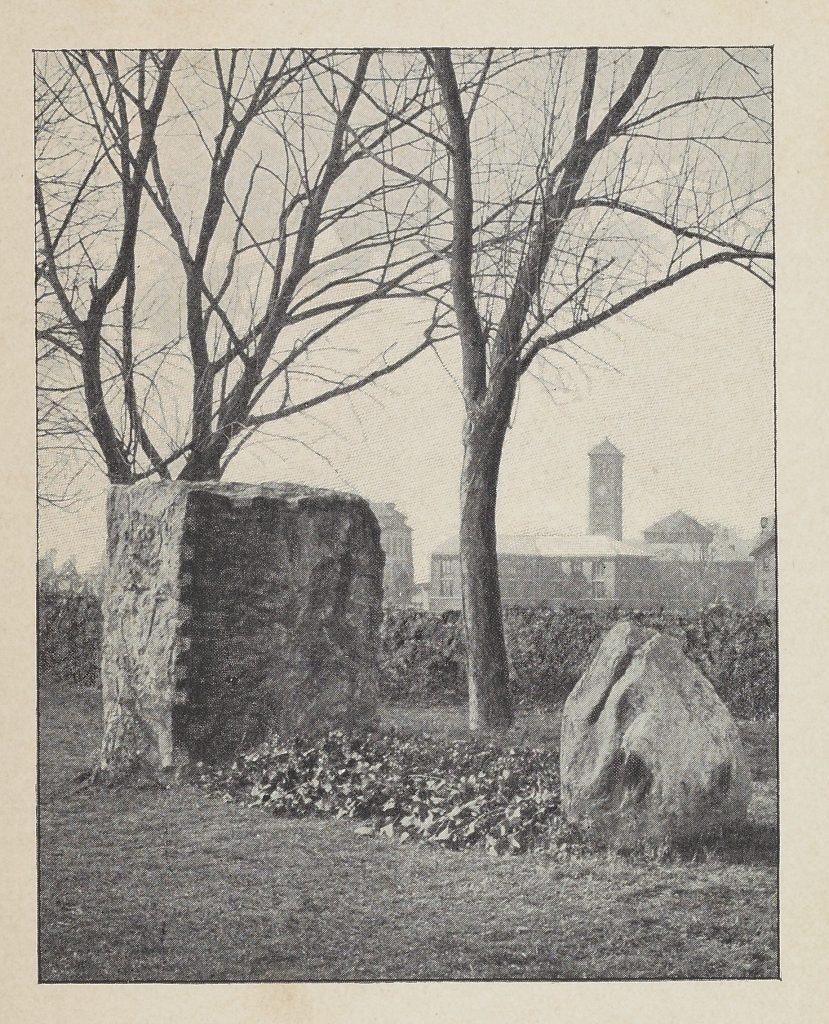

The need for new facilities and teachers to support educational activities made Armstrong a significant fundraiser. He reached out to many northern philanthropists like Collis Potter Huntington and Andrew Carnegie and groups like the American Missionary Association. The tremendous strain of fundraising and promoting his educational theories resulted in Armstrong suffering a debilitating stroke in 1892 during a lecture in New York. C. P. Huntington provided Armstrong with his private railroad car so that the ailing Armstrong could return to Hampton, where he died on May 11, 1893. Armstrong is buried on the campus of Hampton University.

References:

Engs, Robert Francis. Educating The Disfranchised And Disinherited: Samuel Chapman Armstrong And Hampton Institute, 1839-1893. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press, 1999.

Talbot, Edith Armstrong. Samuel Chapman Armstrong: A Bibliographic Study. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1904.

Washington, Booker T. Up From Slavery. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1995.