The Union flotilla steamed downriver after its repulse at Drewry’s Bluff to City Point, Virginia. Commander John Rodgers, the flotilla’s leader, recognized that his ships, USS Monitor, USS Galena, USS Naugatuck, USS Port Royal, and USS Aroostook, were needed to support Major General George B. McClellan’s operations against Richmond. North Atlantic Blockading Squadron commander Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough sent supplies and additional gunboats, including USS Maratanza, Wachusetts, Island Belle, Stepping Stones, and Coeur De Lion, to City Point. This force was to protect the left flank of McClellan’s army.

ENTER SIAH HULETT CARTER

William Keeler called Monitor’s new anchorage at City Point “out of humanity’s reach,” and it was there that he would soon witness new facets of war. The Union ships were operating in “enemy’s country” and consequently, armed guards were posted every evening in expectation of sharpshooters or a raiding party. During the night of May 18, 1862, an alert was called: “Boat ahoy!” And a shot was fired on an approaching boat. Captain Jeffers exclaimed, “Boarders!” All available crewmen rushed onto the deck. Once on deck, Keeler “found the vast array of ‘Monitors’ armed to the teeth drawn up confronting the enemy – a poor trembling contraband – begging not to be shot.”

The contraband, Siah Hulett Carter, confessed that he was the first slave to escape from Shirley Plantation. Carter had been warned by his enslaver, Colonel Hill Carter, not to go on board any of the “Yankee ships” because “the Yankees would carry them out to sea…& throw them overboard.” Siah Carter enlisted as a First-class Ship’s Boy,1 ship’s number fifty-three, on May 19, 1862.

CITY POINT BLUES

On that same day, several officers and sailors went ashore at City Point on a humanitarian mission, only to be ambushed and almost captured by the Confederates. An African American warned the landing party, and they escaped in a shower of minie balls. Once they were back on board, Monitor got underway. The ironclad used its two XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns charged with canister and raked a warehouse where the Confederates had previously been deployed. But they were already gone. The Union ironclad then commenced shelling City Point. Two shells and a load of canister were fired into the Eppes’s family home, Appomattox Manor. The shells passed through the beautiful century-old house before exploding. The residents pleaded that the Union ships not destroy their home. Lieutenant William Jeffers noted, he “did not come to make war on unarmed men or women & children.” USS Monitor then broke off action.

As Monitor awaited further action at City Point, many crew members began to notice several serious problems related to living in an ironclad, painted black, during the heat and humidity of an Eastern Virginia summer. Acting Assistant Paymaster William Keeler noted that the “warm weather is making it very uncomfortable on board our vessel – there is not sufficient ventilation.” A few days later, he reiterated this in a message to his wife: “Yesterday was a hot and uncomfortable day & we lay broiling on or in our iron box or Cage as it has now become.”

Many crew members sought relief from the heat by swimming in the James or Appomattox rivers. Under the supervision of an “officer, and with a boat crew standing by ready to throw a line, any time there is none better,” men with the ability and desire to swim could take off their clothes and jump in the river. First-class Fireman George Geer saw various forms of artwork in the form of tattoos that many a seaman had placed upon their bodies: “I wish you could see the bodies of some of these old sailors: they are regular Picture Books. They have India Ink pricked all over their body. One has a Snake coiled around his leg, some have splendid Coats of Arms of states, American Flags, and most all have Crucifixion of Christ on some part of their body.”

NO TASTE AT ALL

Food was another source of complaint at City Point. George Geer often wrote to his wife about his meals, noting that the sailors would have coffee and crackers cooked in pork fat for breakfast. The men had two gills of grog each day. Other meals would include roast beef and potatoes. Geer described them: “Potatoes taste like I do not know what – anything that has no taste at all – and the Beef is all parts of the Cow cooked together until it is next to a Jelly and will drop into pieces. It is good when there is none better.”

William Keeler also complained to his wife about the food. Emphatically, he noted that there were no fresh fruits or fresh vegetables, nor any fresh meat. It bothered him that there seemed to be plenty of Confederate cattle and other types of food available, but the crew was not allowed to forage for it. The entire crew was now able to supplement their meals with items purchased from the many contrabands who visited the Union ships off City Point. Keeler remembered buying fresh shad at ten cents each.

A DAY’S ROUTINE

George Geer often shared additional details about his daily routine with his wife. He noted that on Sundays, after “breakfast everything is cleaned up about the ship, which takes about one hour, and after that there is nothing to do but keep watch, which amounts to laying around the deck for the saylors (sic)and laying around the engine room for the firemen.” Keeler also wrote that Sunday was “quiet and that the usual routine of daily work, men drilling & at quarters, of painting & scraping & is not carried on.” Sunday was muster day, the day the captain performed an inspection of the crew. The boatswain’s “shrill whistle” would begin the day at 6 a.m., and “everybody must turn out and lash their hammock up and stow them away. All hands make their way on deck, get a pail when their turn comes, and have a good wash.”

William Keeler recalled that the captain’s review began once all the men were “mustered for inspection. Each one is expected to be dressed in his Sunday best…The seamen & petty officers are drawn upon one side of the deck, and the firemen & coal heavers on the other. Each man answers to his name as the Lieut. calls the roll. The Capt. is then informed that the men are ready for inspection. He passes slowly along in front of the lines of men looking closely at their dress, appearance &—’Jones why are your shoes not blacked?’ Jones having no good excuses, the Paymaster’s steward is ordered to stop his grog for a day or two. ‘Lieut. What is this man’s name?’…’Smith, sir.’—’Well have his grog stopped for a week for coming to inspection without a cravat.’ ‘Do you belong to this ship’ he asked one hapless crewman, ‘Yes sir’– Well you are a filthy beast, a disgrace to your ship mates, the dirt on you is absolutely frightful. If I see you again I will have the Master at Arms strip you & scour you with sand & canvas’ & so the inspection goes.”

‘OLD HOG’ JEFFERS

Lieutenant William Nicholson Jeffers III was a seasoned veteran and was considered somewhat of an ordnance specialist. He had already actively served during the war, especially during the Roanoke Island Expedition. Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough had personally named Jeffers to command USS Monitor. Initially, the officers thought very highly of their new commander. Lieutenant Samuel Dana Greene wrote his parents: “Mr. Jeffers is everything desirable, talented, educated, and energetic and experienced in battle.” But the honeymoon would soon be over as Jeffers would quickly lose any esteem the officers and crew held for him. Keeler would later write that things “don’t go as smoothly and pleasantly on board as when we had Capt. Worden. Our new Capt. is a rigid disciplinarian, quick imperious temper and domineering disposition…so far I have got along smoothly enough with Capt. Jeffers, but I am expecting every day that I may forget to touch my hat, or give him the deck in passing or grievously offend him in some little point of etiquette, when I shall get a blast.”

George Geer called Jeffers “a dam’d old hog,” and many other crew members had previously written Worden, addressing the letter, “Our Dear and Honored Captain.” They continued: “These few lines is[sic] from your own crew of the MONITOR with their kindest love to you, Hoping to God that they will soon have the pleasure of welcoming you back to us again soon….Since you left we have no pleasure on board of the MONITOR.” The missive ended, “We remain until Death your Affectionate Crew, The MONITOR Boys.”

JUST TO KILL TIME

Generally, the captain kept to himself, and the men enjoyed their free-time pursuits of reading, writing, mending, fishing, and gambling. Geer remembered, “the gambling still keeps going, though some of the worst ones have lost all he had, and everybody is glad. One boy who only had 50 cents when he commenced has won $40, He is the youngest boy (Thomas Carroll #2) on the ship, and it is fun to see him take money from some of the old gamblers.” Geer also noted that often there were fist fights between the enlisted men. “The English and Irish portions of the crew are out with each other,” the fireman wrote his wife, “and have several times come very close to having a general fight, and have had several small fights. I wish that they would have a big fight and eat each other up, so we get clear of some of them and get some decent men here – if there are any in the navy, which I begin to doubt.”

USS Monitor spent little time in actual combat, so there was much idle time when anchored on guard duty in the James River. William Keeler noted that time was usually spent in reading and conversation and that there wasn’t much else to do “to kill time.” He wrote his wife, “Here we lie, day after day & week after week, prisoners to all purposes, no going ashore – no nothing, but eat, drink & sleep, & while away the tedious hours as best we may.”

FIRE!

While there were few diversions, excitement was more often caused by the unexpected. During the early hours of June 22, a fire broke out in Monitor’s galley. According to Paymaster Keeler, it was “a narrow escape last night from destruction.” The wooden backing, where the stove’s stovepipe passed through the deck, caught fire and burned to within six feet of one of the shell rooms before it was discovered. It appeared that embers from the stack caused the blaze, but it was quickly extinguished. George Geer commented: “I suppose nothing will be said about it, as people would smile at the idea of an iron ship getting on Fire, but they do not know we have wood inside, But there would be very little chance for a fire to get under much headway as there is always some 10 to 12 on watch at a time. In all Men of War there is an arrangement to drown the Power Magazine and Shell Room. Here we can, by simply turning a Lock, fill them with water in five minutes, so there would be no chance of us blowing up.”

Nevertheless, the stove was damaged beyond repair, so Keeler reported, “our breakfast was a scanty one, crackers & coffee, the latter being made in the fire room, in one of the furnaces.” Shortly thereafter, a fireplace was rigged on deck using bricks and iron plates to enable the cook to produce meals.

FRESH AIR

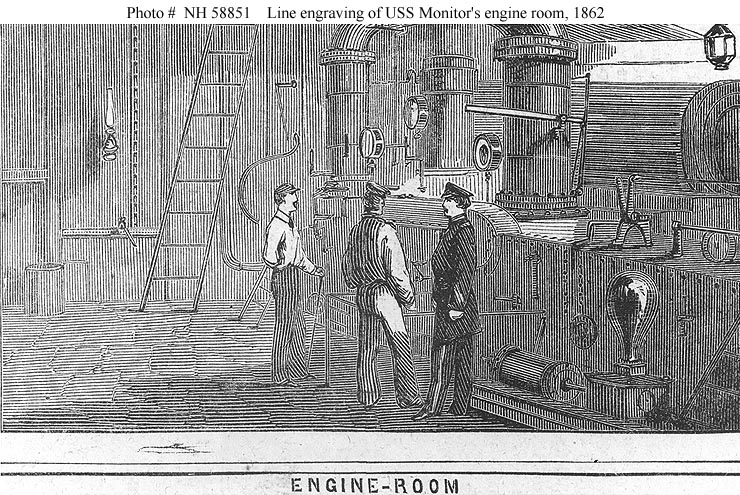

Ventilation within the ship was one of the most painful problems for those living in Monitor. John Ericsson wrote First Assistant Engineer Issac Newton: “You have had a severe trial and can not imagine anything more monotonous and disagreeable than life onboard the MONITOR at anchor in the James River during the hot season.” Geer knew this to be true as the ironclad was not properly ventilated for men to live in, in hot weather, and he said, “I do not think she will ever go in another action until she has some alteration made, as the men would drop at the Guns before they fought half an hour.” The fireman noted that temperatures throughout the ship were just intolerable: 110 degrees in the storeroom, 127 degrees in the engine room, 155 degrees in the galley, and 85 degrees on the berth deck! Geer concluded this letter to his wife stating, “so you can see what a hell we have.”

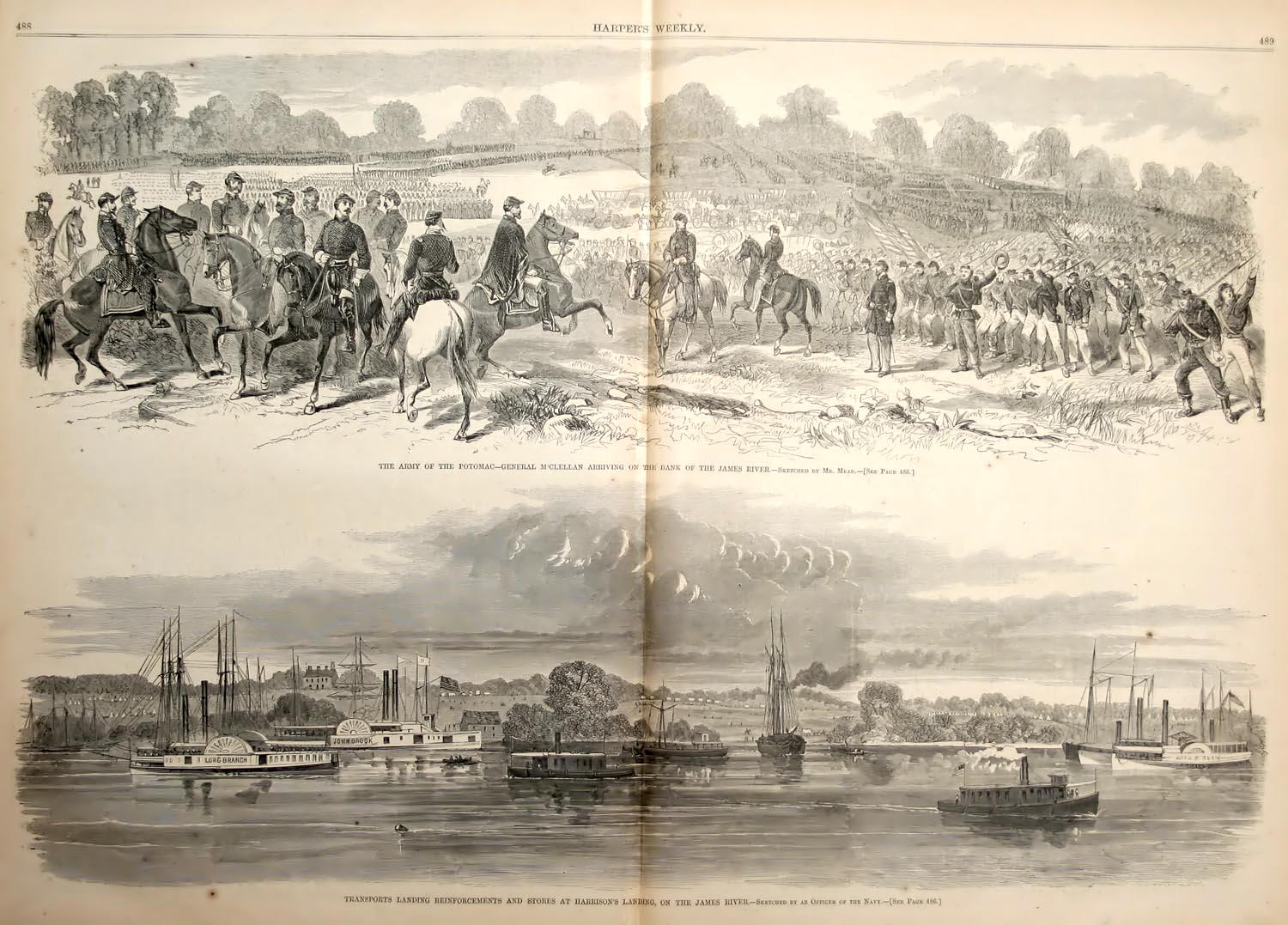

The ironclad’s complement became rather lackluster as they waited at City Point for General McClellan to make his final push on Richmond. On June 25, 1862, however, crew members could hear the almost constant roar of artillery in the direction of Richmond. It was the Battle of Oak Grove. Two days later, McClellan’s army was defeated during the Battle of Gaines Mill and began its change of base to Harrison’s Landing on the James River.

UP THE APPOMATTOX

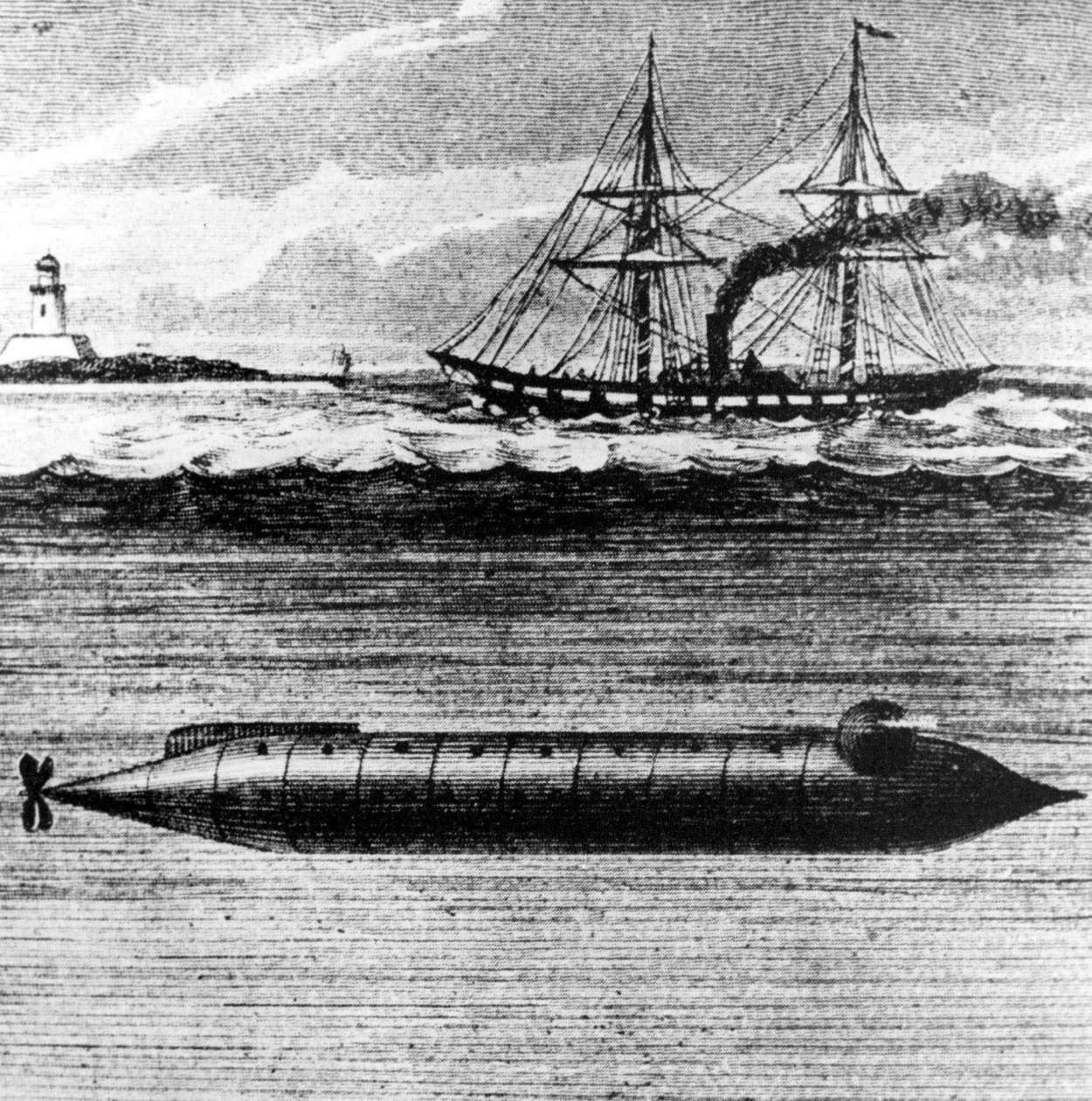

Monitor’s crew did not hear the sound of that battle, as they were deployed on a special mission to steam up the Appomattox River to destroy the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad bridge. This task force also included USS Port Royal, Mahaska, Southfield, Jacob Bell, Stepping Stones, Satellite, and Island Belle, as well as the hand-propelled submarine USS Alligator. This unusual submersible craft was designed by Brutus de Villeroi of Philadelphia and carried two spar torpedoes. It was described as a “submarine battery intended to work beneath the water. It resembles in appearance & is about the size of a large steam boiler pointed at both ends, with a row of small gas lights along the top & a manhole for entrance. It is sunk by admitting water into one of water-tight compartments…& is propelled by a means of a screw turned by the men inside.” The expedition’s purpose was to use Alligator to blow up the Appomattox River railroad bridge. If that proved to be successful, the submarine would then be used to clear a channel through the Drewry’s Bluff obstructions or to torpedo the ironclad CSS Richmond. Most observers questioned the value of this craft.

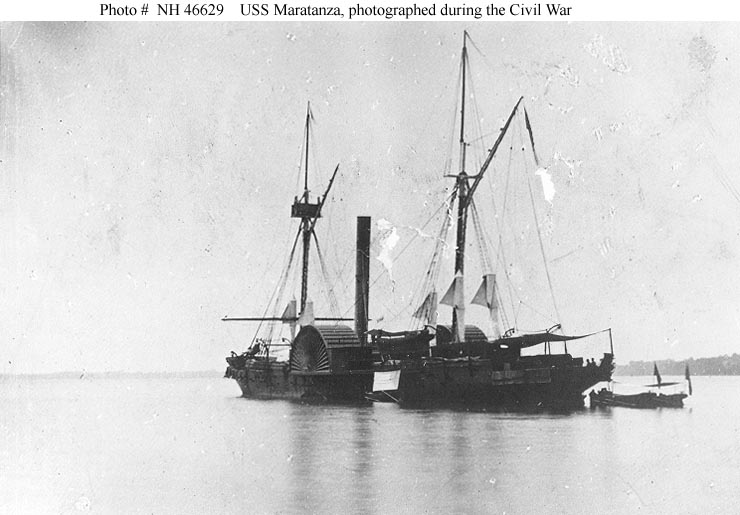

The task force encountered constant sharpshooting as the ships worked their way up the narrow channel. Maratanza ran aground, and the expedition was subsequently abandoned. As Maratanza was freed, Island Belle became stuck in the shallow. Then news reached the Union ships of McClellan’s defeat at Gaines Mill and the subsequent need to bring all gunboats to Harrison’s Landing to help protect the Federals’ retreating army. Island Belle was abandoned and set afire. All gunboats were ordered into the James River. Galena and Maratanza were able to shell the advancing Confederates during the July 1, 1862, Battle of Malvern Hill. USS Monitor did not participate, as it could not effectively elevate its Dahlgrens to provide ground support fire, so it was detailed back to City Point.

PRIZE MONEY

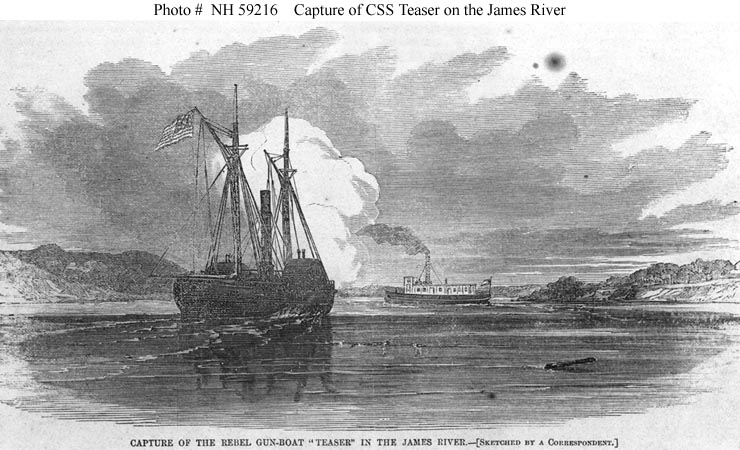

Once McClellan’s army was safely encamped at Harrison’s Landing, the US Navy sent Monitor and Maratanza up the James River to investigate Confederate naval activity. On July 4, 1862, the two Union ships encountered CSS Teaser when they rounded Turkey Point. Formerly an 80-foot-long tug, Teaser was now armed with one thirty-two-pounder rifle and one twelve-pounder gun. This gunboat had fought with distinction during the Battle of Hampton Roads; however, it was no match for either Federal ship. The first shot from Maratanza was high; yet, the next shot of the canister prompted the Confederates to abandon their gunboat. Just as they left Teaser, a second shell struck its boiler and left it dead in the water. When the Federals inspected their prize, they discovered that Lt. Hunter Davidson commanded Teaser. Davidson was working with Matthew Fontaine Maury on developing electric battery torpedoes (mines) and preparing documents detailing where the torpedoes were to be placed in the river. Also on the boat — the Confederate hot air balloon and Davidson’s notebook. William Keeler found this of particular interest: “He was one of the officers of the MERRIMAC & in this book was drafts of the MONITOR sketches of the mode of our capture, as they intended to attempt it.” Keeler realized that the capture of Teaser would bring prize money to Monitor’s officers and crew. He reflected that had Monitor captured Merrimac, they would have shared a $1 million prize ($80 million in today’s dollars).

A SPECIAL VISIT

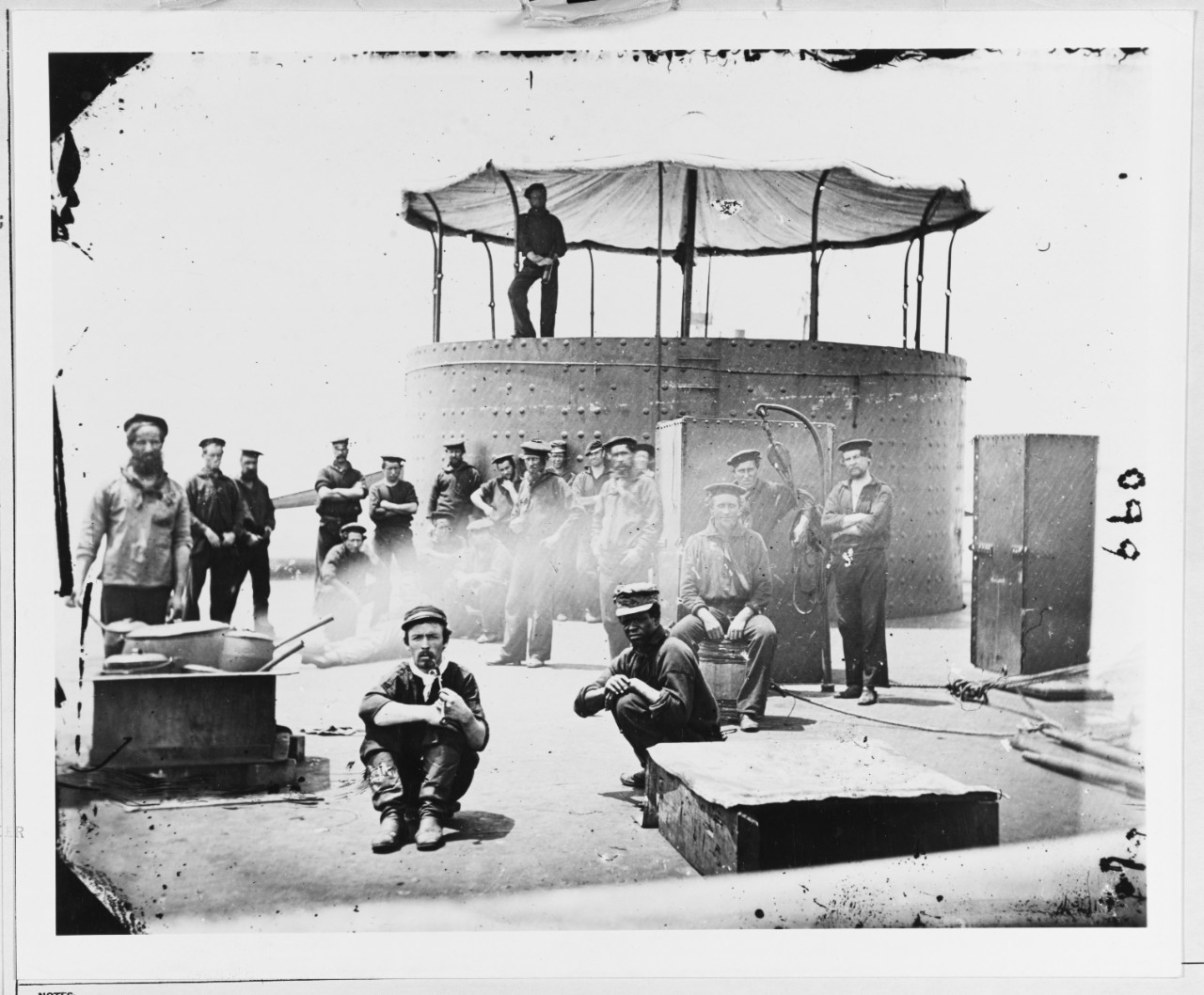

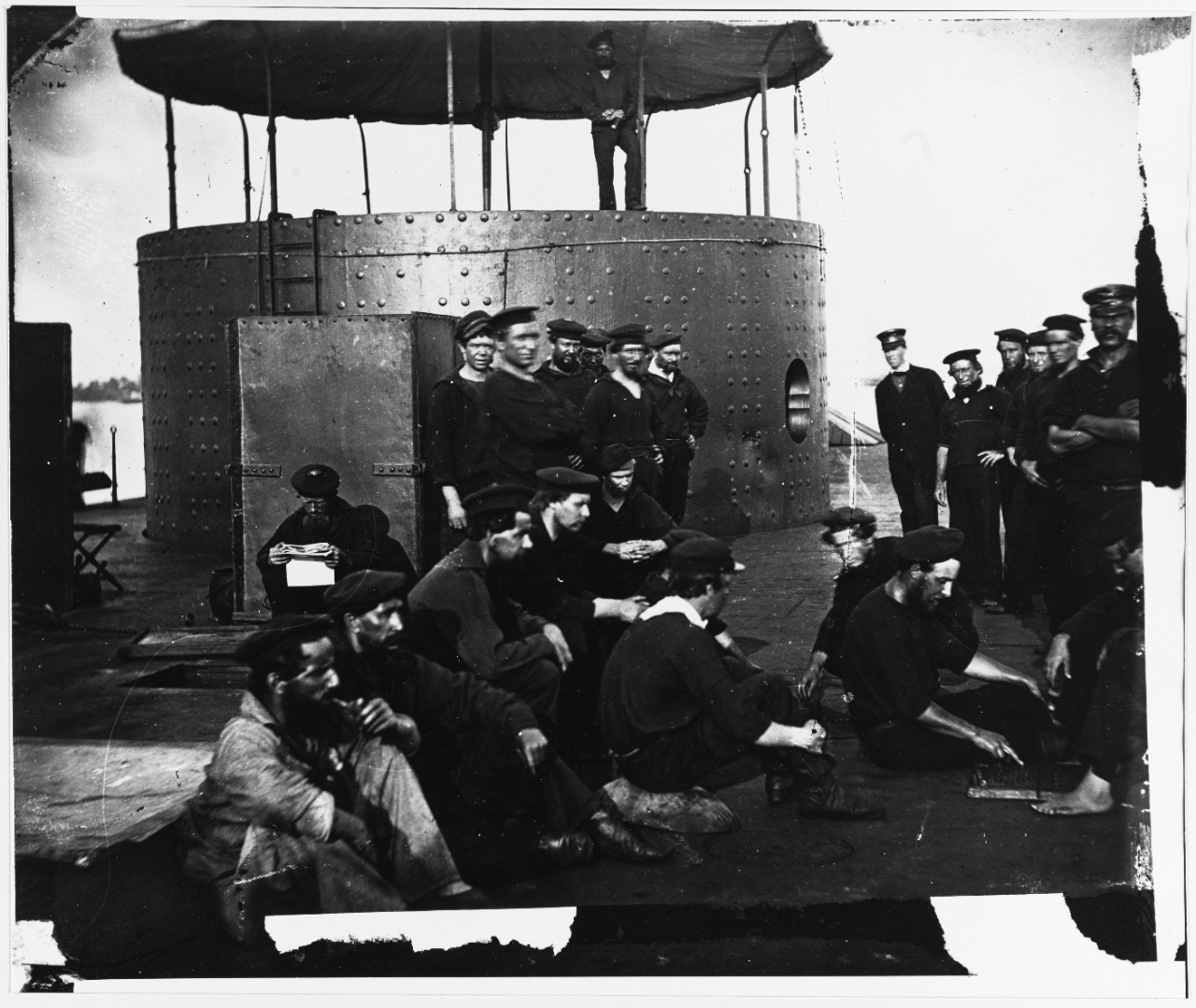

Monitor continued its service in the James River throughout July. On July 9, the ironclad was visited once again by President Abraham Lincoln who was joined by Assistant Secretary of War Franklin Blair and Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough. Also touring Monitor that day was photographer James E. Gibson, who had studied under Mathew Brady. Gibson was at Harrison’s Landing photographing McClellan’s army. While there, Gibson also took several images of the ironclad’s officers and crew. The views of the crew captured “the Monitor Boys” reading newspapers, playing checkers, smoking, and cooking on a stove. Gibson created the only known photographic images made of Monitor. That same day, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles made the James River Flotilla a separate command. Goldsborough considered this an insult and requested reassignment. Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee replaced him on September 2, 1862. The new squadron was placed under the command of the controversial Antarctic explorer and instigator of the infamous Trent Affair, Captain Charles Wilkes.

MERRIMAC ON THE BRAIN

While Wilkes agreed that Monitor was defective and required repairs, the continued fear of the emergence of CSS Richmond (still referred to as Merrimac II) kept Monitor stationed in the James River between City Point and Harrison’s Landing, “in constant preparation for the MERRIMAC….Some of us will die off one of these days with MERRIMAC-on-the-brain,” Paymaster Keeler believed. He continued, “The disease is raging furiously, especially among those inclined to old fogyism.” While Keeler acknowledged that Monitor was considered the savior of the US Navy, since only it could contest the advance of the newest Confederate ironclad, it meant that the officers and crew were left as “close prisoners in the bowels of our iron monster, not a very enviable situation I assure you in this hot weather.”

HOT, HOTTER, HOTTEST

The heat and inactivity had a definite negative impact on the crew’s morale. The soaring temperatures were only worsened by the flies and mosquitoes. Keeler wrote his wife, “You may imagine me writing this with a towel in one hand brushing off mosquitoes & and wiping off perspiration, my brains in a sort of mix with the buzzing of mosquitoes, buzzing of flies, the trickling of sweat.” A few days later, he continued his lament: “Hot, hotter, hottest–could stand it no longer, so last night I wrapped my blanket around me & took to our iron deck–if the bed was not as insufferably hot as my pen–What with heat, mosquitoes & a gouty Captain have really gone distracted.”

CHANGES

By mid-August, the situation would completely change for Monitor’s men. The food situation had improved since May. The Union sailors were now allowed to forage, and crew members could go on pig hunts or acquire cattle, sheep, fish, and vegetables from the nearby enslaved population. The US Navy also made a major effort to improve the health of the men by providing the James River Flotilla with fresh provisions, including vegetables and fruit.

Monitor’s purpose as guardian of McClellan’s army at Harrison’s Landing concluded in August. Even though McClellan had hoped to resume operations against Richmond via Petersburg, the Army of the Potomac was instead shifted to Aquia Landing to operate with Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia.

Changes also came to the complement of officers. On August 14, 1862, First Assistant Isaac Newton Jr. was detailed as superintendent of construction for the Office of General Inspector of Ironclads at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The next day, Lt. William Jeffers was reassigned, to be replaced by Commander Thomas Holdrup Stevens Jr. Stevens had previously served as captain of USS Maratanza, and was the son of one of the heroes of the 1813 Battle of Lake Erie, Rear Admiral Thomas Holdrup Stevens. The younger Stevens had served in the US Navy since 1836 and saw active service during the first year of the Civil War. He was noted for capturing the yacht CSS America.

Keeler was pleased with this change of command and wrote his wife, “Yesterday our ‘most noble Captain’ bade us adieu & left for the east where he is ordered to superintend the building of ‘ironclads.’ I can assure you we parted from him without any regrets, He is a person of a good deal of scientific attainments, but brutal, selfish & ambitious. Commander Stevens, who takes his place, has the appearance of a quiet and modest man, so far I like him, but I find that first impressions are not always to be trusted. He has the reputation of taking a glass too much occasionally, the curse of the navy.”

BACK TO HAMPTON ROADS

While the change of command was well received, the news that Monitor was ordered back to Hampton Roads was met with overwhelming approval. On Saturday, August 30, 1862, Monitor dropped its anchor off Newport News Point, “but a few yards from the sunken CUMBERLAND.” The ironclad’s sole role was to “blockade James River against the egress of the new MERRIMAC.”

AN INTEMPERATE MAN

Monitor’s month-long assignment in Hampton Roads was a positive change for all. Both the food and the weather were much improved. Stevens proved to be a much more pleasant captain, but he was not destined to stay with the ship for long, as he was an ‘intemperate man.’ It appears that Stevens may have run afoul of a new act by Congress that ended the twice-daily grog ration. The act stated that no liquor would be allowed on US Navy vessels except for medicinal purposes.

Drinking was considered a curse by many of the Monitor Boys. Keeler often wrote to his wife about incidents such as the expedition up the Appomattox River when the ship’s commanders, including Stevens, became too drunk to direct their vessels forward. Another story Keeler shared was particularly sad. Landsman Lawrence Murray, who served as the wardroom steward, had become drunk on shore leave. When he returned to Monitor, he took an ax and tried to split Keeler’s manservant’s (a contraband) head open. Murray was placed in double-irons but somehow managed to get to the ship’s side and jumped overboard. The heavy irons doomed him, and his body was discovered three days later on September 5, 1862. Geer noted that no one would lament his loss, as all Lawrence Murray did was drink and gamble his time and money away without sending support to his wife and child in California.

In the US Navy, drinking spirits was a serious problem shared by both enlisted personnel and officers. However, while enlisted men could drink on duty under supervision (such as when their grog ration was issued), officers drank without care. They were only punished when their intoxication became debilitating. Rumors persisted about Commander Stevens’s drinking habits, which was certainly the cause of his reassignment.

A DRUNKEN FAREWELL

Commander John Pyne Bankhead was named Stevens’s replacement on September 10, 1862. Bankhead arrived on September 15 and advised Stevens that he was being replaced because of a drinking incident a few days before, when he was too drunk to entertain several visitors, including Commodore Thomas Turner, captain of USS New Ironsides. Turner was a leader in Navy temperance circles, and when Stevens fell down drunk in front of him, he reported the incident to the Navy Department. Many crew members were shocked. Geer wrote his wife, “I noticed him particularly that day, and saw slightly under the influence of Liquor, but by no means drunk.” When the crew learned about the circumstances surrounding Stevens’s removal, the officers and men wrote many positive letters on his behalf. When presented with the letters, Stevens gave a brief speech to the crew, and as he got on the tug to leave, the men gave him “9 hearty cheers as ever a man had.”

GOODBYE, HAMPTON ROADS

The new commander, John Pyne Bankhead, was the son of Brigadier General James Bankhead and cousin of Confederate general John Bankhead Magruder. He had served in the US Navy with distinction since 1838, including commanding USS Pembina during the capture of Port Royal Sound; he was called a “superior officer” by Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont. With the arrival of USS New Ironsides, Monitor was relieved of its James River defenses duties. While awaiting a new assignment, the ironclad would remain in Hampton Roads, and the men feasted on fish, crabs, oysters, peaches, watermelons, and more. They enjoyed the fresh ocean breezes and visited Old Point Comfort or Norfolk when on leave. Furthermore, the men enjoyed the new command atmosphere. On September 30, 1862, USS Monitor was detailed to the Washington Navy Yard for repairs. The long, hot summer was over at last.

- Explanatory Footnote: First-class Ship’s Boy was a rating established by the US Navy in 1798. It was a rating for juvenile apprentices, ages 15 to 18 (a powder monkey would be rated a Ship’s Boy.) When Siah Carter enlisted to become a member of the USS Monitor crew, although he was 23 years old, he received this rank as he had no previous maritime experience.

Source: John V. Quarstein, The Monitor Boys, Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011.