Artifacts are more than the sum of their parts. Rather than seeing artifacts as just things, we should instead see them as silent storytellers, enlightening whoever may listen with tales of their making, their application, and their eventual retirement from use. At the end of it all, artifacts are often what remains of people no longer here, and it is through listening to artifacts’ stories that those people live on. The artifact lives too when we lend our ears.

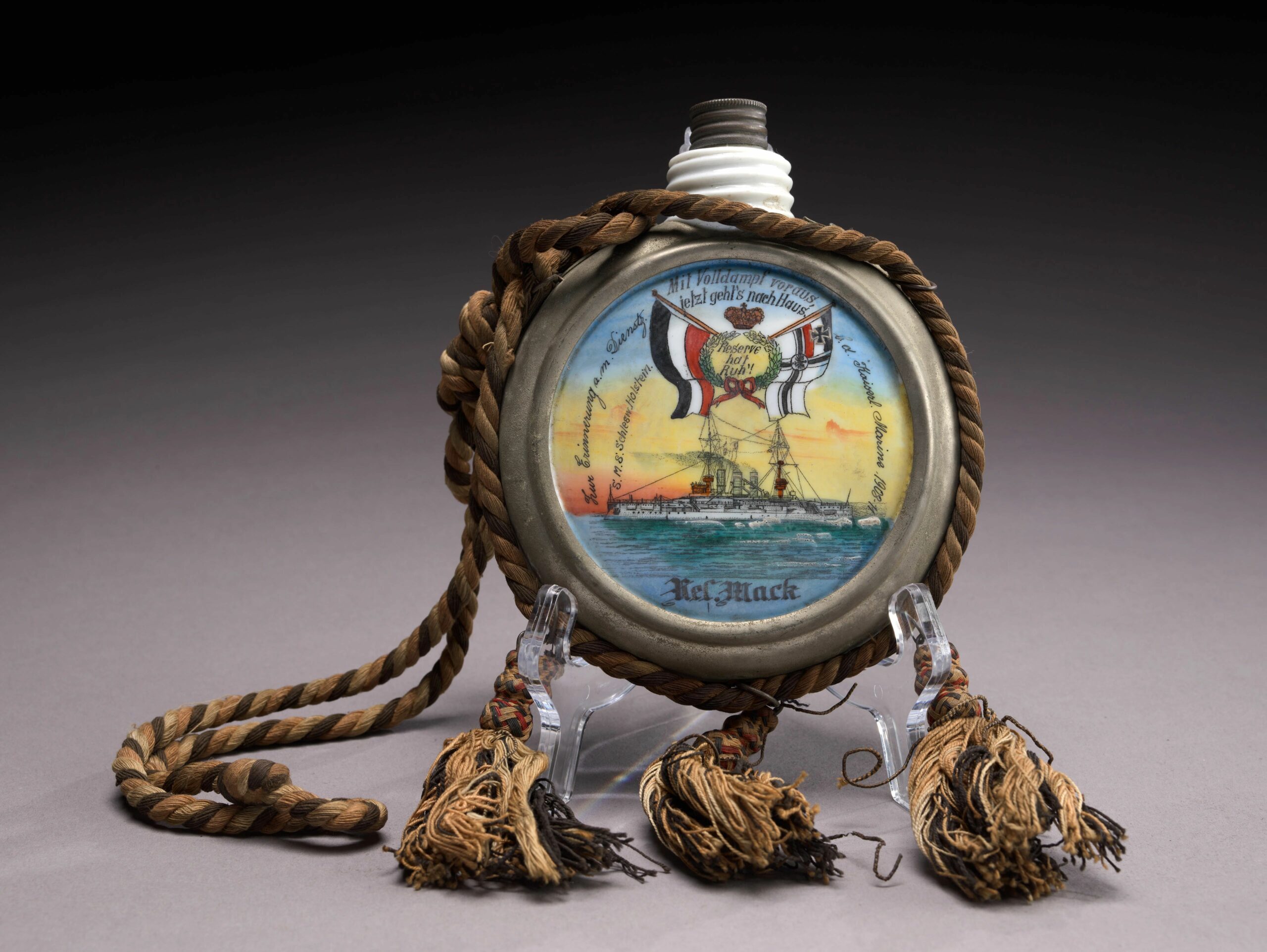

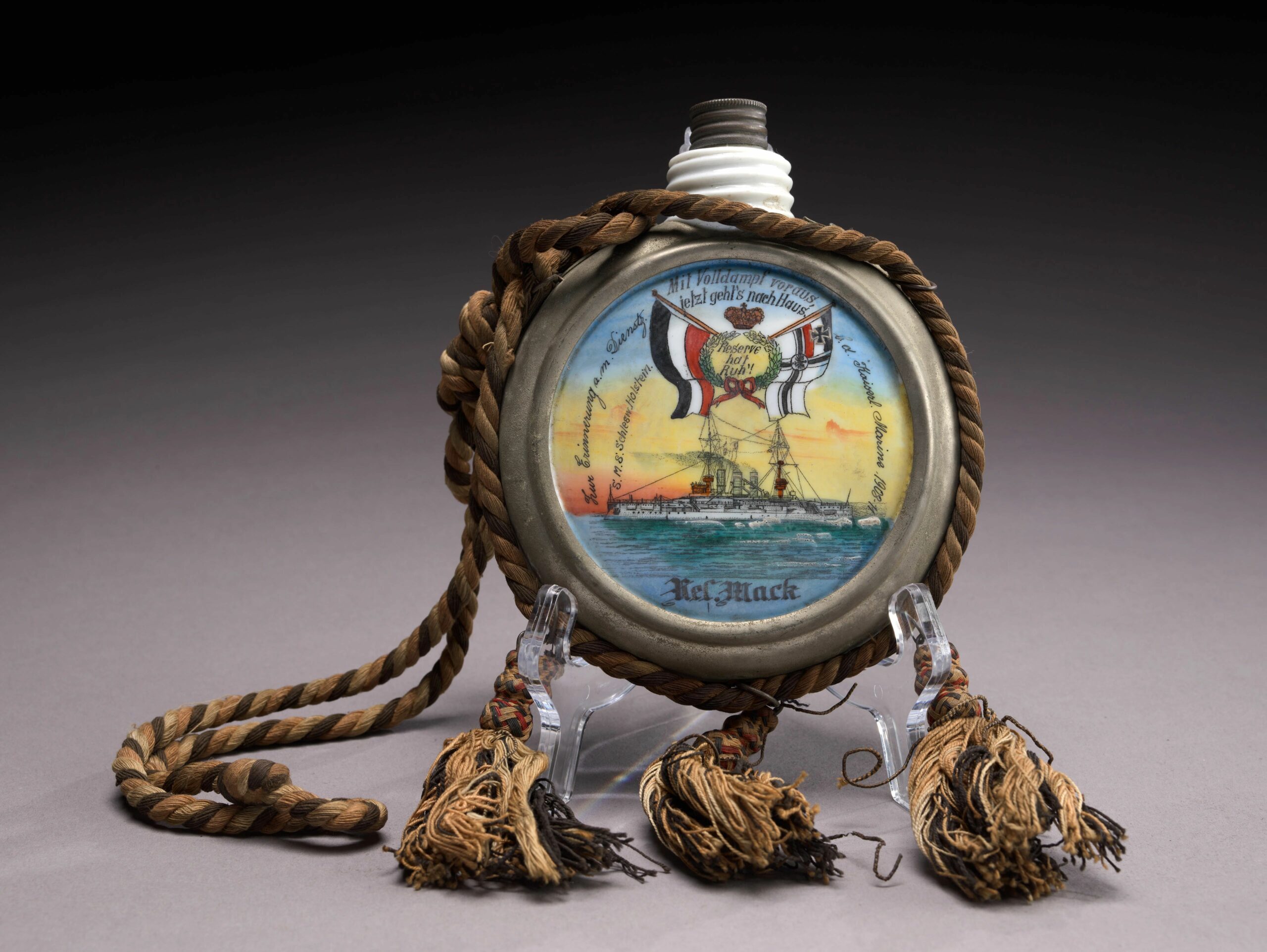

So what does a Prussian schnapps flask have to tell us? Quite a bit. In this case, the flask above holds far more than schnapps (what it was intended to hold). It holds stories. And I would like to share three of those stories. This is the first in my three-part series; a story will be released in a blog post over the next three weeks.

The First Story: A Souvenir for Service

This flask was not just a flask but a souvenir for service in Imperial Germany, known as a “Reservist” or “Regimental” flask. These flasks, and other souvenirs, were primarily made from 1890 to 1914 and were commissioned by active duty servicemen who were coming to the end of their mandatory service.1 The government-mandated service was somewhat unique — men signed up at age 17 and would sign up with a specific regiment. They then stayed with that regiment for their entire term of service, including training. After completing their term, they entered into the reserves until the age of 45.

For those who wanted to commemorate their service, some forethought had to be given. These souvenirs were not last-minute, spur-of-the- moment purchases; rather, they were expensive and took three months to fabricate. Typically, a group of enlisted would order their souvenirs together to reduce costs, and even then, these souvenirs would cost five to seven weeks’ wages! Understandably, only 10% of servicemen were able to purchase a souvenir. The most popular was a walking stick (the least expensive), followed by beer steins (the most collected item today), and then ceramic hand pipes, picture frames, and schnapps flasks, like ours above. For those who planned ahead and were able to spend the money, a very special, personalized souvenir could be taken home. And once brought home, these mementos would often be displayed on a shelf or in a cabinet rather than used at all.2

So let’s dive into how these commemorative items were decorated. Typically, they were personalized and would have the name of the enlisted (sometimes the names of all the men in their regiment), the regiment they were in, iconography to signify their military branch (cavalry represented by a mounted horse, artillery by cannons or other guns, and the navy by the ship served on), and colors to represent the nation-state the regiment was from. The colors were represented in painted wreaths or ropes on steins and in actual ropes or cording on the flasks – black, white, and red for Prussia, green and white for Saxony, and blue and white for Bavaria. The Mariners’ Museum & Park’s flask has a cord of white, red, and black, so we know that this naval regiment served in Prussia. Usually, there would be an image or a quadripartite series of images (an image in four parts) to show off the travels (and sometimes scandalous affairs!) that the regiment engaged in during their years of service. When these souvenirs were first made, they were hand-painted, but as they became more popular, they were industrially produced. Both the steins and flasks would be encased or lidded with pewter and usually had a pewter finial with some symbol of state — an eagle, cannon, or miniature monument of an important figure – like Kaiser Wilhelm II or Otto von Bismarck.

With those standards established, let’s take a deeper dive into our flask. We’ll start with the reverse side. At center is the Seiner Majestäts Schiff (S.M.S.) Schleswig-Holstein at sea, which sits below a wreathed cartouche that says Reserve hat Ruh! That translates to “Reserve has peace.” Above the wreath is written Mit Volldampt voraus, jetzt geht’s nach Haus, meaning, “With full steam ahead, Now we are going home.” On either side of the wreath are the flags of Prussia and the ensign flag, and above is the crown of Imperial Germany. To the left and right of the center are cartouche phrases referencing the service: (L) Zur Erinnerung a.m. Dienst S.M.S. Schleswig Holstein, “In memory for service S.M.S. Schleswig Holstein,” and (R) b.d. Kaiserl. Marine, 1908-11, at the Imperial Marine, 1908-11. Below the ship is Res. Mack – the name of the reservist who owned this flask. It gets a bit more scandalous on the front, though…

At the center, in a red-outlined heart, is the sailor with his lover, whom he had to leave behind at home. Around the central heart-shaped image, however, are images of the nefarious jaunts the sailor went on while at sea – and these include a different woman in every port! But not to fear, because this sailor will always return to his love, for even though he may find comfort in other sweethearts, his heart belongs to his sweetheart back home … or at least that is what the German folk song quoted on the flask seems to imply. The text begins at the top left and moves counterclockwise with the quadripartite imagery (note the different women in each section), and reads as follows:

| Ein Mädchen welch Marine traut | A girl who trusts Marine |

| hat meißt auf losen Sand gebaut | has often built on loose sand |

| Hier liebt Marine nur zum Scherz | Here Marine loves just for fun |

| dem Lieb daheim gehört das Herz | the heart belongs to the love at home |

| Muß ich denn muß ich denn | must I then must I then |

| zum Städtelein hinaus, | leave the city |

| Städtelein hinaus und du | leave the city and you |

| mein Schatz bleibst hier. | My sweetheart stays here. |

Seems a bit scandalous if you ask me, and like something you’d want to keep in a private cupboard rather than out on display to discuss while entertaining guests. But, to each their own, and maybe Reservist Mack had a very understanding wife! Maybe?

There’s one remaining facet to this souvenir’s story, and it is on the dark side. The period in which these reservist souvenirs were made was also a period that saw an influx of statuary erected in Imperial Germany. Monuments of German intellectuals, political leaders, and especially of Kaiser Wilhelm II and Otto von Bismarck were built all over Imperial Germany and seen more in the smaller, rural villages where most German citizens lived. But with these monuments came a rising sense of nationalism that became part of the larger national identity held tightly by Germans that did not dissipate until 1945. This nationalism pervaded the everyday, and with it came a world of small-scale objects — monuments in miniature. Enter the reservist steins, walking sticks, pipes, and flasks — atop each, a small monument with a symbol of state. Not only would the servicemen ending their time in the military take home a souvenir, but they could take home their own small monument of their fearless leaders, the embodiment of Germany itself. It was in this way that German nationalism invaded the quotidian and became part of the everyday lives of their citizens.3

With that, we have come to the end of Part 1 of the Imperial German Reservist’s Flask miniseries. Please come back next week for Part 2, and hear another story that is held within its small porcelain walls – so long as we choose to listen.

Endnotes

1 Kaiser Wilhelm II of Imperial Germany actually shortened the mandatory service term to two years; however, the exception to this rule was a period of three years of service for those in the cavalry and some in the navy.

2 Helmut Walser Smith, “Monuments, Kitsch, and the Sense of Nation in Imperial Germany,” in Central European History 49, no. 3/4 (December 2016): 328-9, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26291406.

3 Ibid, 324-28.