I’ll be honest. I have never been fishing on a boat. Let me clarify: I have never been fishing on or off a boat. I held a fishing pole once as a child. However, once a summer camp friend accidentally got a fishing hook stuck in his neck, I decided the fisherman’s life was not for me. At the end of the day, I just don’t get the appeal.

Little did I know that, while exploring my heritage and ancestry, I would discover a surprising piece of my family’s history: I come from fishermen and captains of oyster boats! I had no clue that I had this connection to maritime history, which made me think of The Mariners’ mission: The Mariners’ Museum and Park connects people to the world’s waters, because through the waters – through our shared maritime heritage – we are connected to one another.

As I worked on writing this blog post, I kept wondering, “What is so interesting about oysters?”

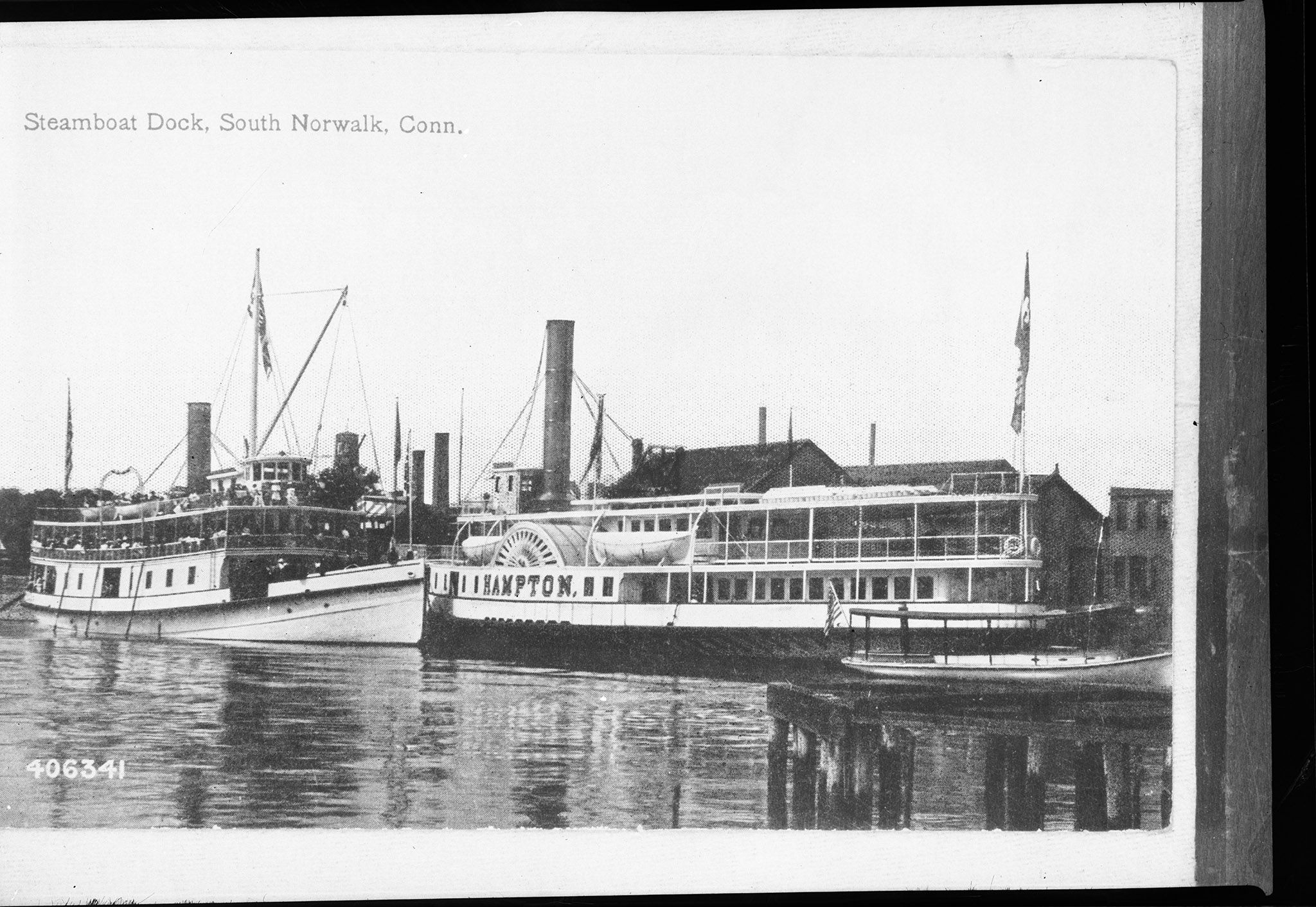

Marvin Beach –off the coast of East Norwalk, Connecticut– is a crucial spot in history for my family. As seen in the background of this picture pulled from our Collection, Norwalk is a beachside city known for its busy port and suburban streets. Below, you can see South Norwalk’s port with the steamer Hampton in the foreground.

My grandfather’s grandfather (my second great-grandfather) came to America from Sweden. He settled in Norwalk and met his wife, Martha, who came to America from Denmark at a young age years earlier with her family (which I can track as far back as my third-great grandfather, but that is a different story). After marriage, Robert and Martha moved around Norwalk for a bit with their first daughter, Eleanor. Finally, they saved up enough money to build a house on a plot of land less than a five-minute walk to Marvin Beach. From there, they raised two more children –Gladys, and the youngest, Roberta– my grandfather’s mother. Their house was the only house on that stretch of land for a while – land that eventually became Roland Avenue and a house that was in my family until my grandfather had to sell it.

From the moment he was able to start his career in America, it seemed my second great-grandfather was destined to be a captain. Before his enlistment into World War I in 1917, Robert was a steamboat captain. Shortly after returning home in 1919, Robert shifted careers to become an oyster boat captain.

Similarly, Martha’s brother, Frederick –my second-great granduncle– was also an oyster boat captain. Martha’s other brothers, Peter and Albert, ran an oyster shop and worked as a carpenter for the local shipyard, respectively. My second-great-grandmother, Martha, seemed to be surrounded by sea captains and oystermen. One could imagine that family holidays must have smelled a lot like the ocean.

Connecticut has a consequential albeit brief history with oystering. By the late 19th century and early 20th, oyster cultivation had developed into a major industry, mainly due to the Sealshipt Oyster Company. As I searched our catalog for images to include in this blog, I stumbled upon only one artifact tied to the Sealshipt Oyster Company: a shipping container shown below. Such containers could carry upwards of four to five gallons each and would be filled to the brim with shucked, cleaned oysters packed with ice between the container’s insulated porcelain walls. This insulation method kept the oysters fresh longer and with no need to freeze them.

Starting in South Norwalk, west of Norwalk Harbor, The Sealshipt Oyster Company created a monopoly among east coast shippers – owning upwards of 100 individual oyster shipping businesses and contractors – by 1910. However, because of overcapitalization and mismanagement, Sealshipt was forced into bankruptcy. In April 1914, the Company was sold at a receiver’s sale in which the committee of buyers reorganized it as North Atlantic Oyster Farms, incorporated July 1, 1914. Although this is conjecture, it is likely that my second-great- grandfather, Robert, and his brothers-in-law, Peter and Fred, worked closely with this company throughout their careers after the war.

By the 1800s, oystering boomed in New Haven, Bridgeport, and Norwalk and claimed modest success in other towns along the Connecticut shore. By the mid-19th century, Connecticut led oyster seed production north of New Jersey. However, increases in the coastal human population, industrialization, pollution, and marine traffic –as well as continued overfishing – threatened Connecticut’s oyster beds after 1920, with production falling drastically after 1950. This shows in my family’s history of work after the 1920s. Peter became a gardener, and Robert passed away from a long-standing illness in 1928. Fred seemed to carry on with his oyster affairs, and little is known about their brother Albert. After the war, many documents pertaining to him are absent from research, so the profiles I formed are largely conjecture.

As I wrap up this post, I want to take a moment to reflect. It feels like a “full-circle moment” in which I write my family’s history and put it out into the world. Although I may not have any desire to fish or “set sail on the high seas,” I am still surrounded by the ocean and its fascinating history by interning at America’s National Maritime Museum – The Mariners’ Museum and Park! I encourage anyone reading this to explore your family’s history. You never know what you might uncover and to what extent you, too, are connected to maritime history. For at The Mariners’ Museum and Park, we connect people to the world’s waters, because through these waters, we are connected to one another and to our maritime heritage.

Sources

“Albert Larsen.” Connecticut, U.S., Military Questionnaires, 1919-1920. Ancestry.

“Albert Larsen.” Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication

T624, 1,178 rolls). Norwalk, Connecticut. Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Boyle, Doe. “Oystering in Connecticut, from Colonial Times to the 21st Century.” Connecticut

History. August 27, 2020. https://connecticuthistory.org/oystering-in-connecticut-from-colonial-times-to-today/#:~:text=By%20the%20late%2019th%20century,production%20north%20of%20New%20Jersey.

“Fredrick Larsen.” Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. (NARA microfilm publication

T625, 2076 rolls). Norwalk, Connecticut. Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

“Martha M. Larsen.” United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Twelfth Census of the

United States. 1900. Norwalk, Connecticut. Washington, D.C. National Archives and Records Administration, 1900.

“Martha M. Larsen.” Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Norwalk, Connecticut. (NARA microfilm

publication T624, 1,178 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

“Peter Larsen.” United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Twelfth Census of the United

States, 1900. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900.

“Peter Larsen.” Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication

T624, 1,178 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.