America’s lucrative whaling industry was based along the northeastern coast in the 18th and 19th centuries. While it was a dangerous occupation that required months or even years at sea, products derived from whales were in great demand. Whale oil was used to illuminate homes and streets as well as lighthouses and as a lubricant for machinery. [1] Whale “bone” was more flexible than our bones, and it was thought of as “the plastic of the 1800s.” [2] Whalebones were used in making women’s corsets, hats, and collar stays, among other things. Other uses included soaps, paint, and varnish.

The California Gold Rush

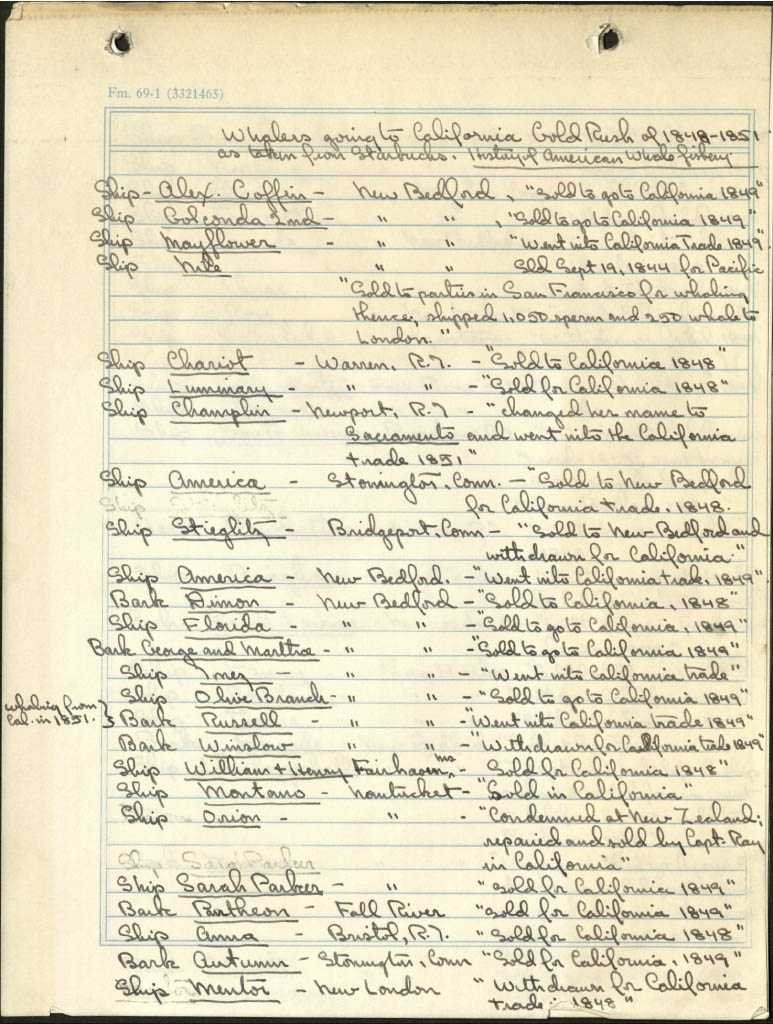

Many of us are familiar with the swift and radical changes brought on by the California Gold Rush in 1848. Connecting this event to the whaling industry would never have occurred to me had I not found research done by Albert M. Barnes, II, whose collection was donated to The Mariners’ Museum in 1986. Mr. Barnes created a list of 59 whaling vessels whose destiny was forever changed by the California Gold Rush.

Whalemen, like thousands of others, caught gold fever and rushed to California. The question was, how to get there? A choice had to be made as to the quickest route: over land, by sea, around the tip of South America, or by sea and land across Panama. In the winter of 1848-1849, the traditional route of migration to the Pacific — the great plains — was impassable due to rain-swollen rivers and mud. Mountain passes were blocked by snow and ice. [3]

This is a typical whaling ship in operation during the Gold Rush. Based in New Bedford, Massachusetts, Charles W. Morgan missed out on Gold Rush fever. She was chasing whales in the South Pacific from 1849 to 1853. [4]

According to historian Sandi Brewster-Walker, “whaling captains had the advantage of experience traveling the 18,000 nautical miles around Cape Hope to get to California.” [5] By December of 1849, most departing whaling vessels were laden with additional passengers, intent on mining gold.

Barnes’ list, titled “Whalers going to California Gold Rush of 1849-1851, as taken from Starbucks’ History of American Whale Fishing,” includes some hints at what was to become, such as “voyage broken up by crew deserting to California” and “sailed from Salem March 19, 1846 with company of 63; was hauled up on the bank at Sacramento and afterwards used as a prison.” Only a few returned to whaling a few years later.

Every Ship, Bark, Brig & schooner in Port are deserted by their crews. Some of them are regularly laid up and Captains & all have gone to the mines. Seamans wages are one hundred & twenty five dollars a month and we have to beg them to go at this price. It will cost a fortune to get a crew and we are obliged to make an agreement to bring them back or they will not Ship.

─Cleveland Forbes [6]

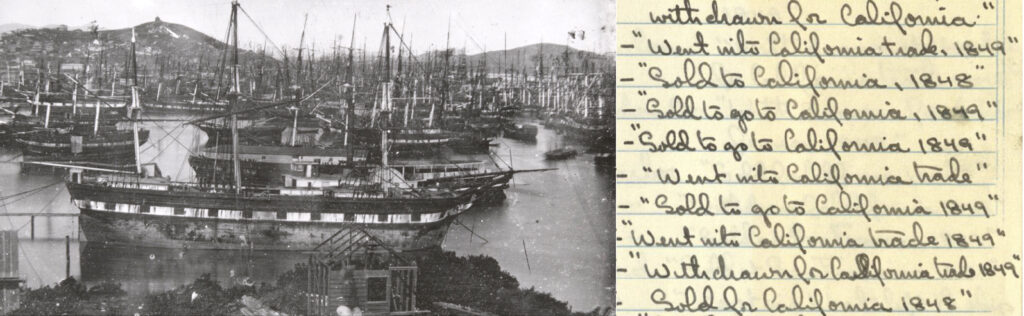

More than 700 ships ended up abandoned in San Francisco Bay. [7] These photographs, taken by William Shew and collected by Barnes, are from the winter of 1852-1853. The view shows San Francisco’s harbor with countless ships anchored. Also noted on the back of the images: “harbor is filled with rotting sailing vessels, crew having deserted to gold fields.”

Buried Ships in San Francisco Harbor

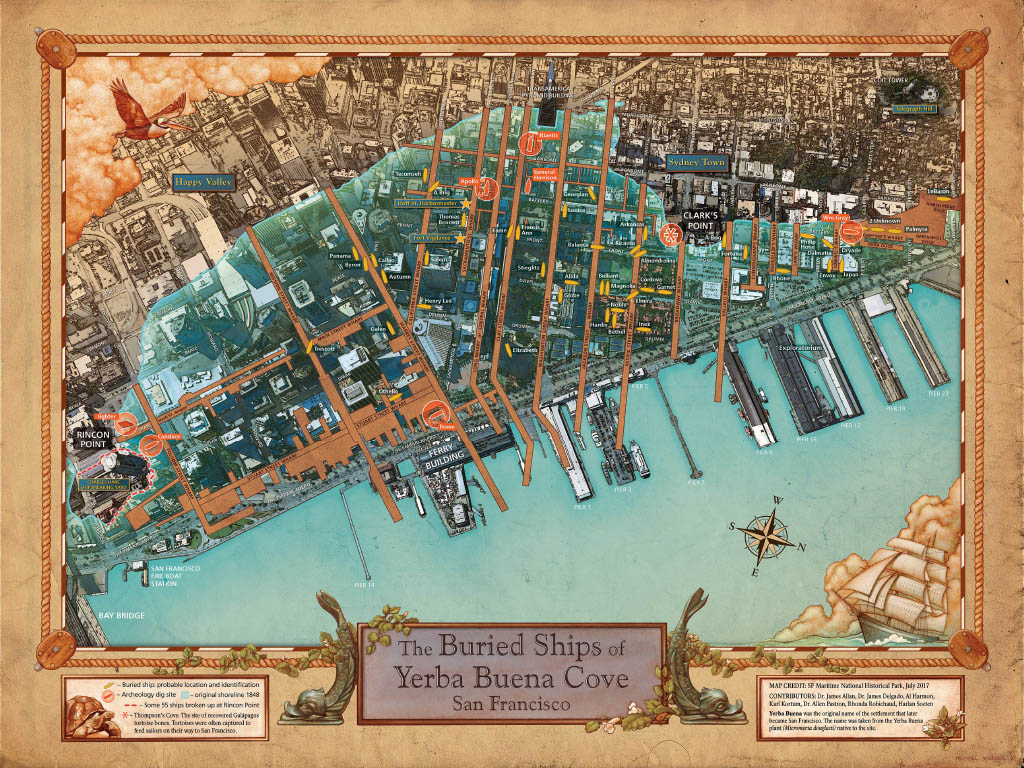

When I lived in San Francisco, I heard about new construction being halted due to archaeology. Thanks to the San Francisco Maritime Historical Society, I’ve learned more about these rotting ships. This map indicates the location of 47 ships that have been located and identified. The City’s shoreline in the 1850s and today is also outlined.

In 1849, San Francisco’s shoreline was called Yerba Buena Cove, “a shallow crescent-shaped bay with exposed tidal mudflats.” Most of the ships eventually sank in the mudflats, but a few were put to use as storeships, hotels or a prison. [7]

In conclusion, whales were saved as a result of gold fever, but only for a few years. The California Gold-Rush played a part in saving the whales, but it had more to do with timing. The chief factor in the decline of whale fishery was oil drilling and processing, initially into kerosene. (8) Today, whaling is prohibited by most countries around the world, and the North Pacific right whale and North Atlantic right whale are endangered species. Established in 1946, the International Whaling Commission works to conserve whales and monitors the regulation of whaling.

Sources:

1. Dolin, Eric Jay (2007). “Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America,” New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

2. McNamara, Robert. Accessed June 29, 2022, https://www.thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070

3. Delgado, James P. (1996). “To California by Sea: A Maritime History of the California Gold Rush,” Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

4. American Offshore Whaling Voyages: A Database, https://whalinghistory.org/av/, Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc. and New Bedford Whaling Museum.

5. Brewster-Walker, Sandi. Accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.massapequapost.com/articles/the-gold-rush-of-1849-whaling-captains-as-gold-miners/

6. Pomfret, John E. (1954). “California Gold Rush Voyages, 1848-1849: Three Original Narratives,” San Marino, CA: Huntington Library.

7. Olmsted, Nancy. “Gold Rush Ships Under San Francisco Streets.” Latitude 38, July 1987, https://www.latitude38.com/magazine/archive/

8. Purrington, Philip (1968). “Whale Fishery of New England,” New Bedford, MA: Reynolds-DeWalt Printing, Inc.

*Special thanks to Gina Bardi, Research Librarian at San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park Research Center