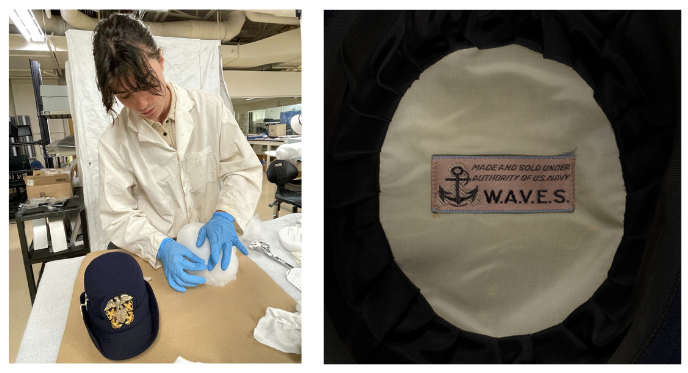

Image 2: Inside label of WAVES hat.

If you’ve ever doubted the influence of fashion on decision-making, even with things as important as military recruiting, this history might change your understanding of the world.

Ahoy there! My name is Oliver Petersen, and I was excited to join the conservation team this summer as a Ted Mittler and Marcia Liebel Preventive Intern under Preventive Conservator Adam Novello. During my time on staff, I studied the process and implementation of preservation strategies relating to the health and safety of the wonderful collection here at The Mariners’ Museum and Park.

My duties included rehousing vulnerable objects, conducting scientific testing on the materials in contact with our objects, navigating pesky pest problems, and monitoring environmental factors like temperature, humidity, and light. I am a recent graduate of the University of Pittsburgh, where I worked to preserve books, paper, photographs, and objects within the school library’s archives and special collections (meaning rare books). This prepared me well for work within the large and varied collection of The Mariners’ Museum and Park.

My first preventive project this summer surrounded the creation of custom mounts for a collection of World War II-era hats from the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service of the US Navy, better known as WAVES. I was quickly drawn to this project as both a history buff and a textile artist, and am excited to share what I learned about working with these special objects and their important place within military, women’s, and fashion history. This history is especially relevant now as the US Navy celebrates its 250th anniversary in 2025.

The WAVES were not the first women to serve in the US Navy, as women volunteered as nurses and in other vital auxiliary positions during the American Revolution, Civil War, and World War I (Guepet 1). In early 1942, soon after the United States joined World War II, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corp (WAAC) was established, leading to a similar position for women in the Navy to be proposed by Representative Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts.

In May of 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order approving the Senate Naval Affairs Committee’s proposal to establish the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) as auxiliary. However, prominent female educators around the country pushed back, such as Dean Harriet Elliot of the University of North Carolina, and Dean C. Mildred Thompson of Vassar College, writing to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, “urging that the WAVES be an integrated part of the Navy, not auxiliary to it” (Guepet 3).

These letters put pressure on the President, leading to July 30, 1942, when Roosevelt signed an executive order officially establishing WAVES as a part of the Navy itself. Professor Elizabeth Raynard of Barnard College would be commissioned as the first-ever female lieutenant in the US Navy just 2 days later. She paved the way for other women, not only just in the Navy but within other branches of the military.

Once the WAVES were established, women began to serve in important non-combat roles such as translators, switchboard operators, aviation mechanics, cryptographers, and much more. It is important to note, however, that this July 1942 decision was not fully integrated, with Black women unable to join. Full integration for African American women was not established until October of 1944, when Harriet Pickens and Frances Wills were admitted as the first Black participants of the WAVES training program (Martin 2).

Between 1942 and the end of the war in 1945, the WAVES had enlisted 73,816 women, 8,745 officers, and nearly 4,000 in-training enlistees, far exceeding the Navy’s early projections for recruitment (NPS 1). This massive success is attributed by modern scholars to the ability of the Navy to associate the WAVES with education and upward mobility, as well as with traditional femininity, which many Americans were concerned would be jeopardized if women joined the male-dominated world of the armed forces.

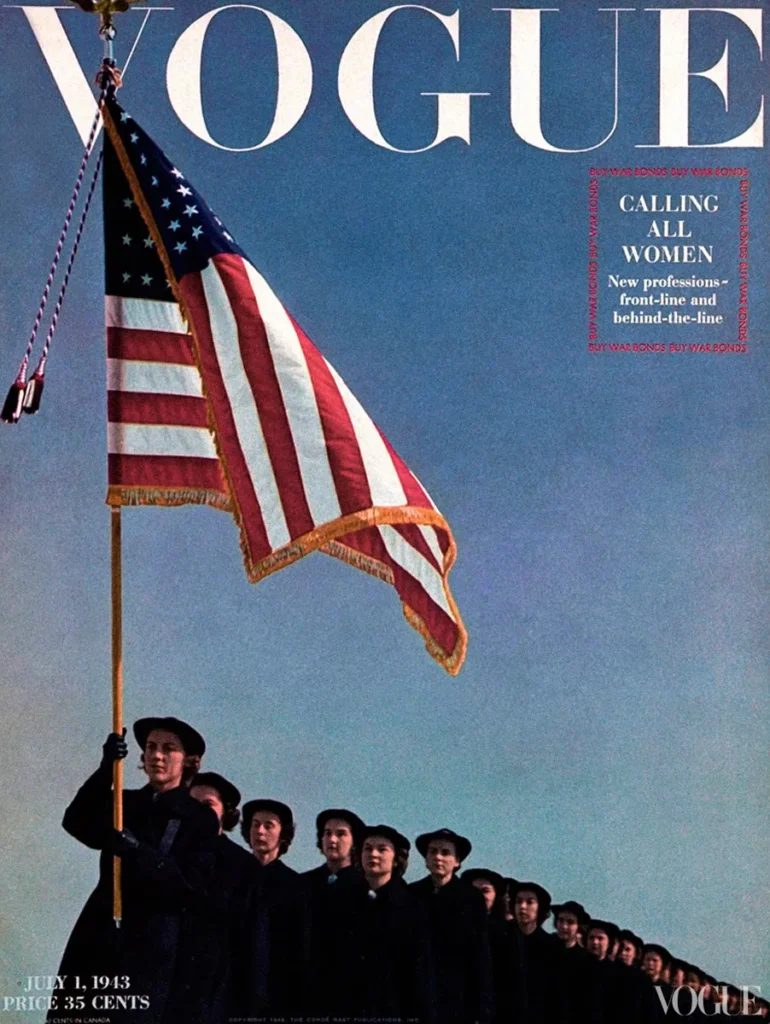

Developing interest through fashion was a large part of the latter goal, as the WAVES used advertising in magazines such as Vogue and Glamour to project a fashionable, yet ladylike, patriotic image (Guise 1). Alongside this, French American couturier Mainbocher, well known for dressing the social elite, was brought on to design the WAVES uniforms, which was a major draw for many.

In the words of WAVES veteran Virginia Gilmore, “[the uniform] was probably the most expensive thing any of us had ever had. Well made. Beautiful material. And you felt so comfortable.” “I knew I would never have designer clothes,” recalled WAVES veteran Eileen Horner Blakely, so there was my opportunity. So when someone says, “Why did you join the Navy?” I say, “Well, number one, blue is my color.” (Homefront Heroines)

By October of 1943, the WAVES uniforms for all ranks were very elaborate, with the officers uniform containing 24 separate pieces, ensuring preparedness in many environments and social situations. An itemized list of WAVES officer and watermen uniform regulations is available here for the curious.

For their heads alone, each officer was meant to have in her possession an officer hat, a navy blue officer hat cover, a white hat cover, a gray hat cover, a hat device, and a havelock. The Mariners’ Museum and Park collection is home to many of these garments. The particular hat that I was first tasked with mounting was a navy blue officer hat with its hat device (in this case, an eagle insignia made of real gold and silver), alongside a blue hat cover.

This hat would have been part of an officer’s service dress, meant to be worn in informal settings or for ceremonial purposes. Regulations required hats to be worn “whenever a WAVE was outdoors, including riding in public vehicles, such as buses, or private vehicles, such as cars” (Ageton 207). Though all the pieces are currently in relatively good condition, it is important to update the storage of an object to best fit its needs as it ages to prevent future damage.

During the rehousing process, materiality was important to keep in mind as interaction between different materials used in a garment can negatively impact long-term stability. For example, this hat includes metal elements in the brass buttons on the sides as well as in the silver and gold insignia on the front. These could discolor or degrade the fabric over time if corrosion or tarnishing occurs.

The plastic lining inside the hat is also prone to damage, as the plastic will become more brittle and inflexible than the wool around it. Therefore, a custom foam mount was required for both the hat and the cover to ensure that the correct shape is held as they age. Alongside this, a mylar barrier was placed between the insignia and the fabric to prevent physical and chemical reactions with other materials.

After much measuring, sizing, and sewing, this officer hat, hat cover, and hat device have been properly mounted and rehoused, ready to be used as a teaching tool for generations to come. The story of the women involved in the WAVES in general, as well as the specific woman whose name is handwritten on the tag of the interior of her officers hat, will continue to be told through these objects as we progress further and further away from World War II. At The Mariner’s Museum and Park, we will continue to honor each garment for its important place within fashion, women’s, and military history.

Sources

Falter, John. “It’s a Woman’s War Too!” Navy WAVES recruiting poster. 1942.

Guepet, Haley. “The WAVES of the US Navy.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, The National World War II Museum, 29 Oct. 2024, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/waves-us-navy.

“July 1 1943.” Vogue Archives, Vogue, archive.vogue.com/issue/19430701. Accessed 1 July 2025.

Martin, Kali. “‘We Made It, Friend’: The First African American Female Officers in the US Navy.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, The National World War II Museum, 23 Feb. 2021, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/african-american-wave-officers-us-navy.

“Navy Haute Couture.” Women & the American Story, The New York Historical Society, 3 Dec. 2024, wams.nyhistory.org/confidence-and-crises/world-war-ii/navy-haute-couture/.

“Uniform Identity: Homefront Heroines: The Waves of World War II.” Homefront Heroines The WAVES of World War II, www.homefrontheroines.com/exhibits/uniform-identity/. Accessed 1 July 2025.“Uniform Regulations, Women’s Reserve, USNR, 1943.” Naval History and Heritage Command, www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/u/womens-reserve-1943.html. Accessed 1 July 2025.