During World War I, a Navy vessel ‘sailed’ the concrete of New York City for three years. The only water it ever encountered was from the sky and the city’s municipal water supply. The battleship, nicknamed “USS Neversail” and the “Street Dreadnaught,” was officially christened USS Recruit.

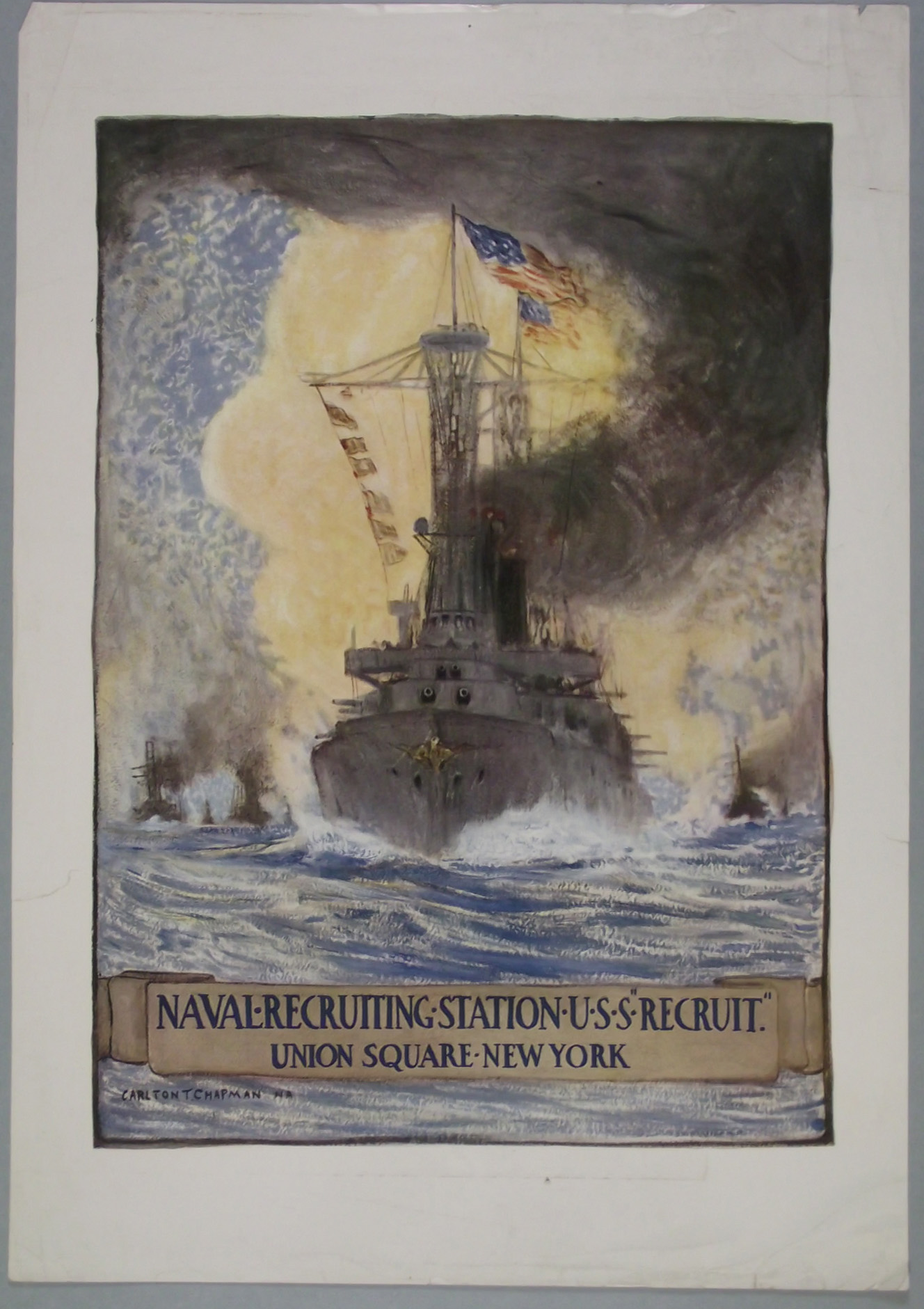

This recruiting poster depicts Recruit proudly steaming through the waves, leading other vessels in its wake. In reality, Recruit was constructed, commissioned, manned, decommissioned, and dismantled without ever touching an ocean. Yet despite being landlocked, the ship played an important role during World War I.

When the United States entered the war in April 1917, localities across the country were given recruitment goals based on their population. But three weeks after the call for volunteers went out, it became apparent that the expected number of recruits would fall short. So, President Woodrow Wilson and Congress instituted a draft in May with the Military Service Act of 1917. Their main concern was to expand the number of troops for ground warfare, therefore limiting the draft to Army enlistees. This left the Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard to find their own recruits.

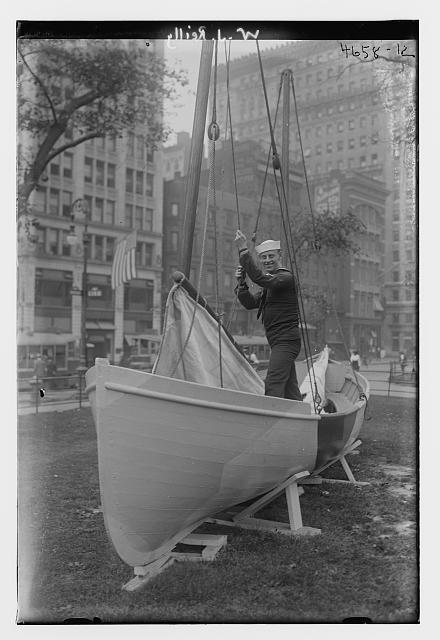

Initially, New York was expected to produce 2,000 volunteers. But New York City Mayor John Purroy Mitchel realized by mid-April that this number would be missed by at least half. He created the Mayor’s Committee for National Defense to find ways to increase recruiting numbers and serve the war effort. One of their ideas was to build a wooden mockup of a dreadnaught battleship and use it as a recruiting station. It was an obvious advertising gimmick, but one they hoped would stir patriotic feelings among citizens while encouraging enlistments.

The idea for the project came from Committee member James Gillespie Blaine Ewing, the chair of the subcommittee on recruiting. Ewing was also a businessman, real estate agent, and assistant to the president of the George A. Fuller Construction Company. Construction costs were estimated to be about $10,000, and the city began taking donations to fund their ship. Materials were donated or provided by suppliers at significant discounts, and Fuller Construction offered its services and employees at no cost. With Ewing at the helm, construction began May 1, 1917, using a design created by architect Donn Baker and illustrator Jules Guerin. Recruit’s design was based on the typical dreadnaught of that time, and they might have used USS Maine as their inspiration. The popular Union Square Park was chosen as the location.

During the three weeks it took to complete construction, people were drawn to the noise and spectacle taking shape in Union Square. However, the project wasn’t without controversy. The New York Tribune reported on May 27, 1917, that there were many comments on the expense and that money was being wasted on a ship that would never sail. Bystanders complained that the sound of hammers “seemed to sing a song of dollars gone to waste.” And that “thousands of feet of lumber” were being purchased when the money could have been better used to feed, clothe, or otherwise ease the suffering of those affected by the war in Europe.

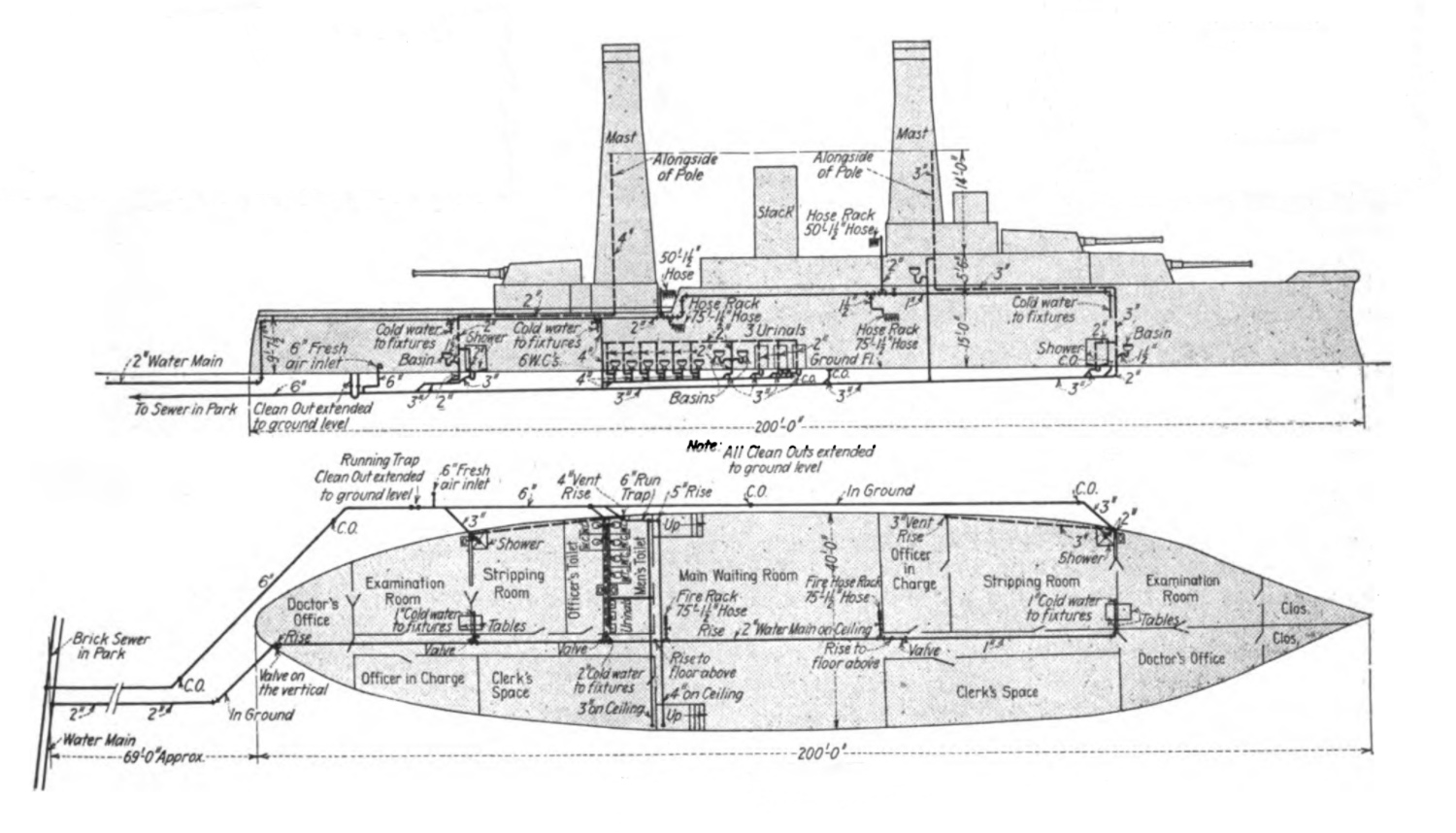

Blaine Ewing refused to provide the project’s final cost for the New York Tribune article, but he did admit that it was more than the initial $10,000 estimate. Some speculated that the number was around $13,000. However, an article in the June 8, 1917, trade journal Sanitary and Heating Engineering reported the cost was significantly higher. The feature described the installation of Recruit’s plumbing system, the companies involved, and material contributions, and that the overall cost was closer to $22,000, a rather considerable sum in 1917. That equates to $479,191 in today’s dollars! About two-thirds of the total was covered by cash donations, with the remainder made up of materials and supplies provided by manufacturers.

Recruit had turrets, a fake smokestack, and two 50-foot masts. Most of the wood was covered with canvas to create smooth surfaces, and then the entire ship was painted traditional battleship grey. To onlookers, Recruit must have looked like a cross between a child’s wooden toy and a large ship that got dropped into the middle of the city and then sunk to its waterline once it touched the concrete. Some design elements were obviously fake, like the solid wood guns in the turrets that had large wooden stars covering where the bore would have been on a real gun. The ship was also slightly smaller than an actual dreadnaught battleship at 200 feet long and 40 feet wide. In comparison, USS Maine measured 393’ 11” long and 72’ 3” at the beam.

But other features on the ship were real. Recruit had working guns fitted at the port and starboard sides, searchlights, a wireless radio station, steering apparatus, binnacles, signaling equipment, deck railings, an anchor, lifeboats, and a fully equipped bridge. The ship was also fitted with a ventilation system that could do a complete air exchange in the structure as often as ten times an hour. This kept the humidity down and moderated the temperature in warmer weather.

Construction was completed in time for a formal christening on May 30, 1917, with the Mayor’s wife, Mrs. Olive Mitchel, doing the honors by smashing a bottle of champagne. The Mayor then officially turned Recruit over to the Navy, making it the only actively commissioned, landlocked US Navy vessel at that time. The ship had three decks: the upper or weather deck, the second deck with berthing compartments and toilets, and the ground level, which was used as the recruiting station. This area contained a large central waiting area flanked on each side with an examination room, clerk’s office, and a stripping room with showers, offering only cold water. Even though one manufacturer had arranged to loan the city radiators and a heating system for the replica, the decision was made to put off the installation until October. (Possibly a precaution should Blaine Ewing’s idea turn out to be a failure.)

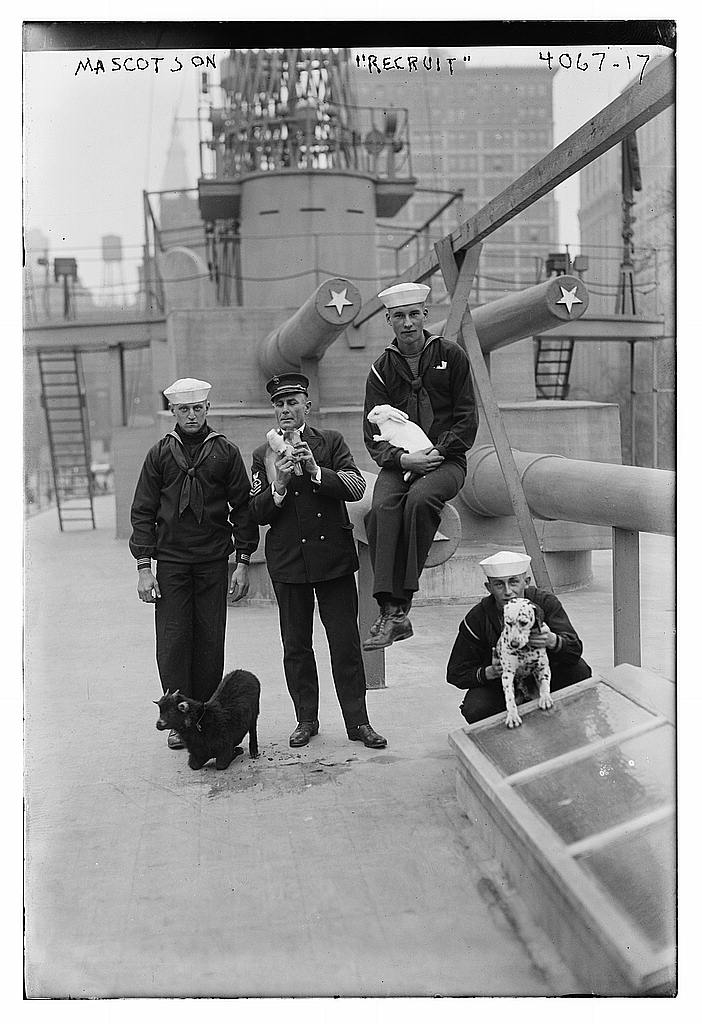

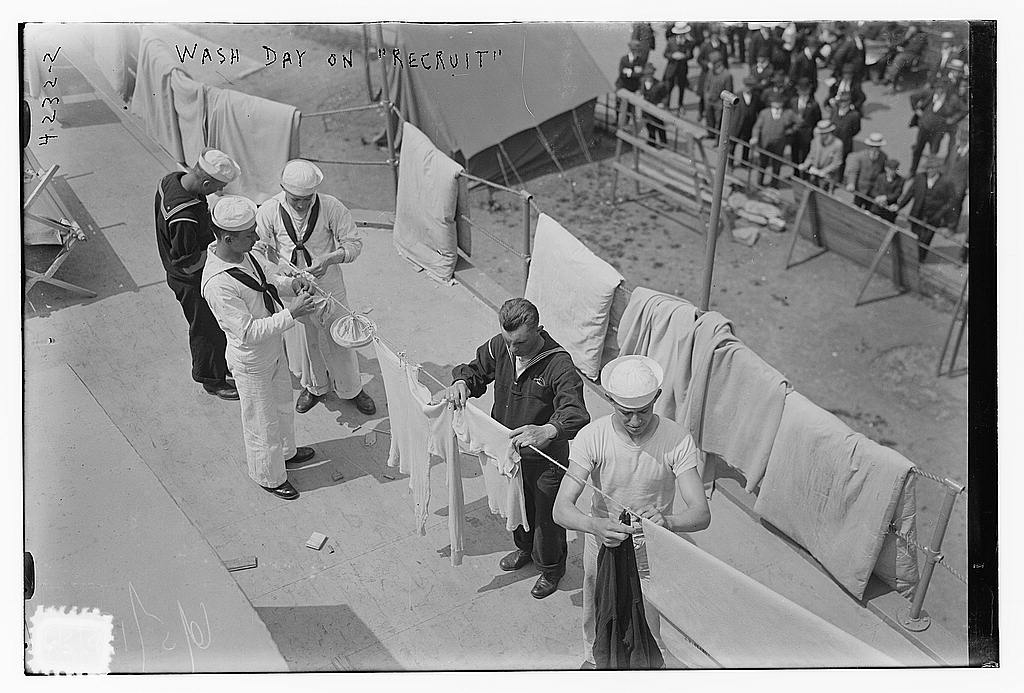

At its commissioning, Recruit had an assigned crew of 63 men who would live and work onboard under the command of Acting Captain C.F. Pierce. Their duties were typical of sailors serving the Navy and included early morning reveille, cleaning, drills, inspections, deck watches, and ship maintenance. They also had to help advertise the merits of Naval service. Three times a day, the ship was open to visitors who were encouraged to look around, ask questions, and even try out the handheld navigational instruments under the direction of the sailors. The crew didn’t try to hide some of the less desirable tasks, either. Once a week, they were seen hand washing their laundry in buckets and draping it over the ship’s railings to dry. The ship’s mascots – a white rabbit, Dalmatian puppy, a bird, and a goat named General Byng (said to have a rather bad attitude at times) – were also on hand to greet the public.

The novelty of the landlocked battleship attracted large numbers of curious visitors, many of whom were considering whether or not to volunteer for Naval service. Visits from dignitaries and military personnel from France, the United Kingdom, and Australia were seen as opportunities to strengthen ties with other governments. And a visit from Chief Big Eagle along with a small delegation from the Lenape tribe in Delaware was used to encourage more Indigenous people to participate in the war.

Lieutenant Wells Hawk, a press agent assigned to the ship, proved to be very effective in drawing attention to Recruit. He asked newspapers across the country to encourage visitors to the city to stop by and see the dreadnaught. Some papers printed tickets for their readers to cut out and use for a free tour, assuring readers that the publication would pay the Navy for the tour when the military mailed the tickets back to the paper. It doesn’t appear that visitors were ever charged for tours, but perhaps the idea of a special ticket made their visit feel more important and enhanced patriotic feelings. And no doubt it probably increased newspaper sales.

The ship’s weather deck was the perfect place to hold speeches, concerts, operatic performances, vaudeville acts, pledge drives, dances, bond and liberty loan rallies, and even boxing matches. The rallies refreshed the community’s patriotic fervor and raised large sums of money. A single event often brought in thousands of dollars. Young women dressed in red, white, and blue outfits traveled through the crowds with buckets to gather donations, encouraging attendees to give. The boxing matches, one of the events that did require paid admission, brought in so many people that the opposite side of the deck was packed and hundreds watched from the concrete below.

Recruit’s own Navy band grew from about 20 men to well over 100 talented and well-respected musicians. Along with entertaining visitors to the dreadnaught, the band marched in parades and provided music at events around the city. The Navy also got requests to send the band to other states for performances. The ship’s Glee Club, quartet, and its troop of actors staged skits and musicals, including their well-received rendition of HMS Pinafore. The publicity garnered by newspaper announcements about these events kept the novelty of the dreadnaught alive.

Blaine Ewing’s idea to build a fake battleship produced some incredible results: more than 25,000 enlistments were attributed to Recruit, and thousands of dollars were raised. But after the war ended on November 11, 1918, the question of what to do with the landlocked ship loomed. For a while, activities on the battleship carried on as usual with the expectation that the ship would remain as a recruiting station and training site for Naval recruits. The Band, Glee Club, and actors continued participating in events, but these gradually transitioned to providing background music for sporting events or entertainment for society socials and luncheons. While still used for some rallies, concerts, and speeches, the weather deck became the site for debutante balls and dances. But after the ship’s band marched in the last Victory parade and the public’s attention started turning from the war, things changed. It became obvious that Recruit’s usefulness in Union Square was coming to an end.

Newspapers reported that the Navy would hold Recruit’s decommissioning ceremony on March 17, 1920, and that the ship would be dismantled shortly afterward, moved to Coney Island Amusement Park, and then reassembled. The city’s expectation was that Recruit would still draw crowds of curious people while still functioning as a recruiting station. Newspaper advertisements about the upcoming summer season at Coney Island mentioned Recruit and opportunities to visit the ship. But at some point between the ship’s disassembly and the amusement park’s opening, the idea was dropped. It doesn’t look like a public explanation was ever given. It is possible that the cost of rebuilding and maintaining the ship was going to be too high, or there were concerns that the war-weary public wouldn’t continue to embrace the ship as a novelty. Or perhaps it was because Mayor John Purroy Mitchel was no longer around to support such a plan. Mitchel lost his party’s nomination for reelection. Just days after his term ended on January 1, 1918, Mitchel heeded his own advice for men to enlist and joined the Army Air Corps. He was killed in a flight training accident in Louisiana on July 8, 1918.

Despite its end, Recruit’s legacy isn’t just solely due to the novelty or number of enlistees the ship produced. Since then, four other landlocked ships have been built to serve the Navy and Coast Guard: USS Electrician in Virginia, USS Recruit in San Diego, USS Commodore in Maryland, and USS Bluejacket in Florida. Due to time and base closings, none of them are still in use. But like the first Recruit in New York City, all of them served to give sailors a sense of what life aboard a ship would be like. Many modern sailors have been able to say that their first assignment was on one of these landlocked training ships.

It has been said that men have always dreamt of the sea. Perhaps the same could be said about ships. If so, Chapman’s recruiting poster portrays that perfectly – the dream of the landlocked USS Recruit sailing the waves, leading other ships into battle and sailors to victory.