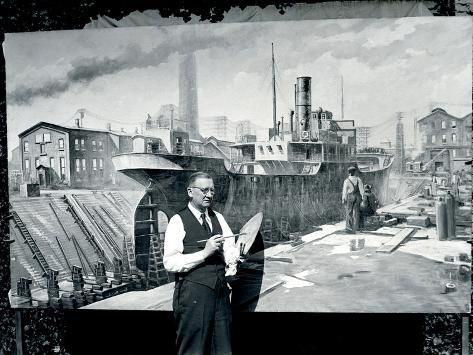

Thomas Catlett Skinner’s office was a loft overlooking the dry dock at the Newport News shipyard. Frequently he would gather his tools and wander through the yard, stopping to observe and document the many scenes unfolding before him. A vat of molten steel. Red hot metal beams being bent into shape. Yards of canvas transformed into sails. The welcome respite of a lunch break. The intensity of a foreman’s face. A ship being refitted for the next voyage. Scenes that were rarely seen by anyone outside the shipyard and activities that many people never knew existed.

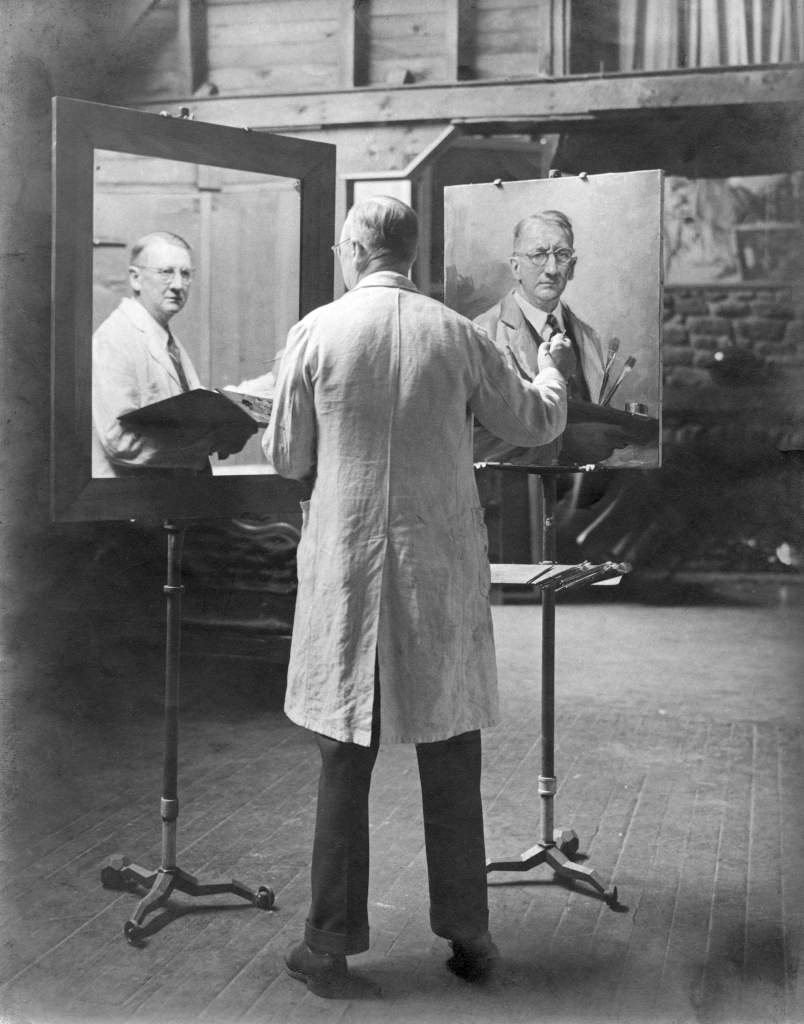

Skinner’s tools were paint, pencils, canvas and paper. His loft workspace shook with the unending pounding from riveting hammers and vibrations from heavy machinery. And when he set up his easel beside the piers, dry docks and workers, he was surrounded by noise and dirt and exposed to the fickleness of the weather. Yet despite the adversity, he created amazing drawings and paintings that transport the viewer back in time. His body of work contains striking, colorful images that make it easy to imagine all the noises in the shipyard, the sound and feeling of waves acting on a ship and the harsh sounds of battle. Today, as part of our 90th Anniversary celebration, we take a look at the Mariners’ Museum staff artist, Thomas Skinner, some of his work, and its importance.

The Early Years

Thomas Skinner probably never imagined that one day he would end up in a shipyard. Born in Kittawa, Kentucky in 1888, he spent most of his childhood in Waynesville, North Carolina. From an early age, he was almost always seen with a pencil and sketch pad in hand, drawing whatever caught his fancy, and his parents were very supportive. So when the time came for the family to move back to Kentucky, they probably weren’t surprised that Thomas decided he wanted to head to New York City to study art.

He arrived in New York at the right time. An informal group of artists who called themselves the Ashcan Painters or the “Ash Can School” was in its heyday. Their tongue-in-cheek name was a dig at the numerous ‘schools of art’ in New York and a description of the group’s subject matter, gritty, realistic portrayals of street life and the city’s inhabitants. Paintings that didn’t romanticize, but showed it all, the ash cans on the sidewalks, prostitutes, street urchins, mud, and even the horse dung in the streets. The work by these artists dubbed “New York Realists” and his travels in Europe to study realistic paintings by Dutch and French artists with Ash Can painter Robert Henri would highly influence Skinner’s own work.

At 26 years of age, and while in Paris in 1914, Skinner married French artist Therese Louise Desiree Tribolati. He brought her back to his home in New York City that August. He continued to work on his art during the war years, exhibiting and selling some pieces for the commercial market and magazine covers. One of his paintings, an impressionistic depiction of flags flying from the porches of a row of houses, was shown in the prestigious Allied War Exhibition in 1918. This non-juried show, which was organized by well-known art collector Duncan Phillips, didn’t offer any prize money, but being included as one of the featured artists did serve as recognition of Skinner’s talent and exposed more of his work to the public. That same year, Skinner would be called up for military duty at the end of the war. He spent his entire military career (September 1918 to March 1919) at Camp Hancock in Georgia. The camp served as an airfield and a training facility for National Guard troops before they were sent overseas. Skinner achieved the rank of private First Class but what his job entailed appears to have been lost to time, and if he spoke of his military service to friends and fellow veterans, that information apparently never made it into articles or his biographical information. After his return from service, Skinner decided to study at one of the “schools of art” in New York and attended the well-known Arts Students League from 1920-1921 and at some point he also attended the National Academy of Design.

The Shipyard Years

In 1930, Skinner was asked by his brother-in-law, Homer L. Ferguson, to move to Newport News and serve as the staff artist for the newly opened Mariners’ Museum. Ferguson, married to Skinner’s sister Eliza, was President of the Newport News Shipyard and the museum’s first Director. He tasked Skinner with creating art for the museum, while at the same time documenting the scenes at the yard. Was the job offer made because of any financial issues the Skinner’s might have been having? Was it influenced by Archer Huntington who was an avid art collector and step-son of the shipyard’s founder? That is unknown, but what did happen, whether or not it was Ferguson’s intent, was that the drawings and paintings Skinner created served to promote not only America’s industrial might, but also the prosperity of the shipyard. Both noble causes for a country in the midst of the Great Depression, citizens who were desperately looking for hope for the future and their own lives, and the local community who relied heavily on the shipyard as an employer. It is difficult to determine whether Skinner’s salary was paid by the shipyard, the museum, or both institutions, but years later his 1942 World War II draft card lists both institutions as his employers.

When he began work at the shipyard, Skinner was still finding his way artistically. His style was still evolving but it was becoming more and more influenced by what he saw around him. The grit, sounds, smells, and industrial scenes, that didn’t lend themselves to an impressionistic or romantic interpretation, began to take over, harkening back to his Ash Can School influences. The longer he would work there, the more the style took over his artistic vision.

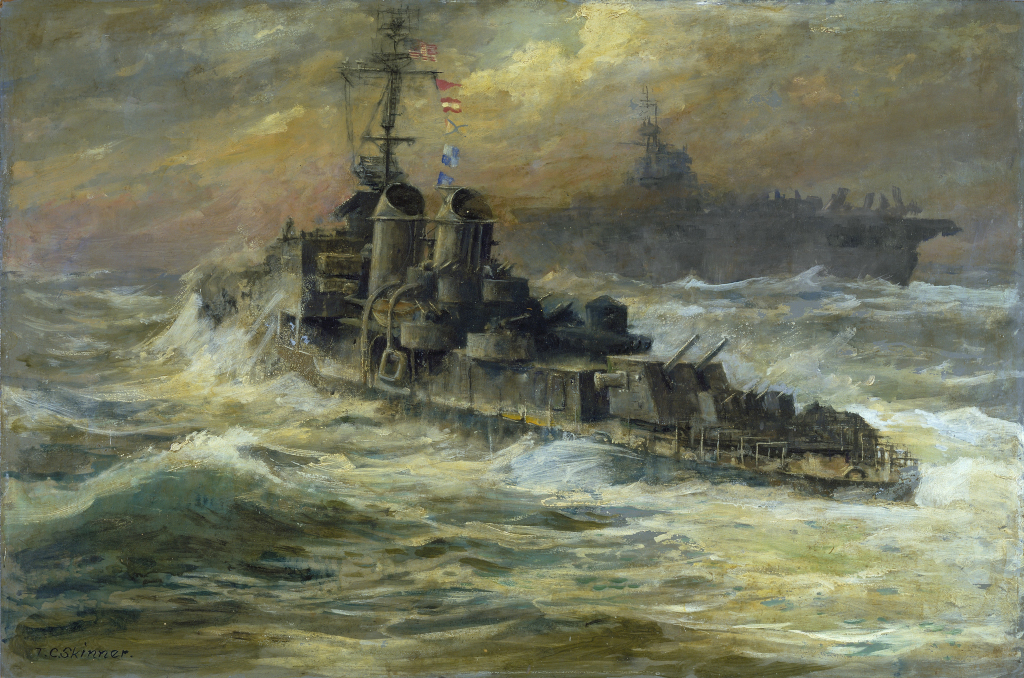

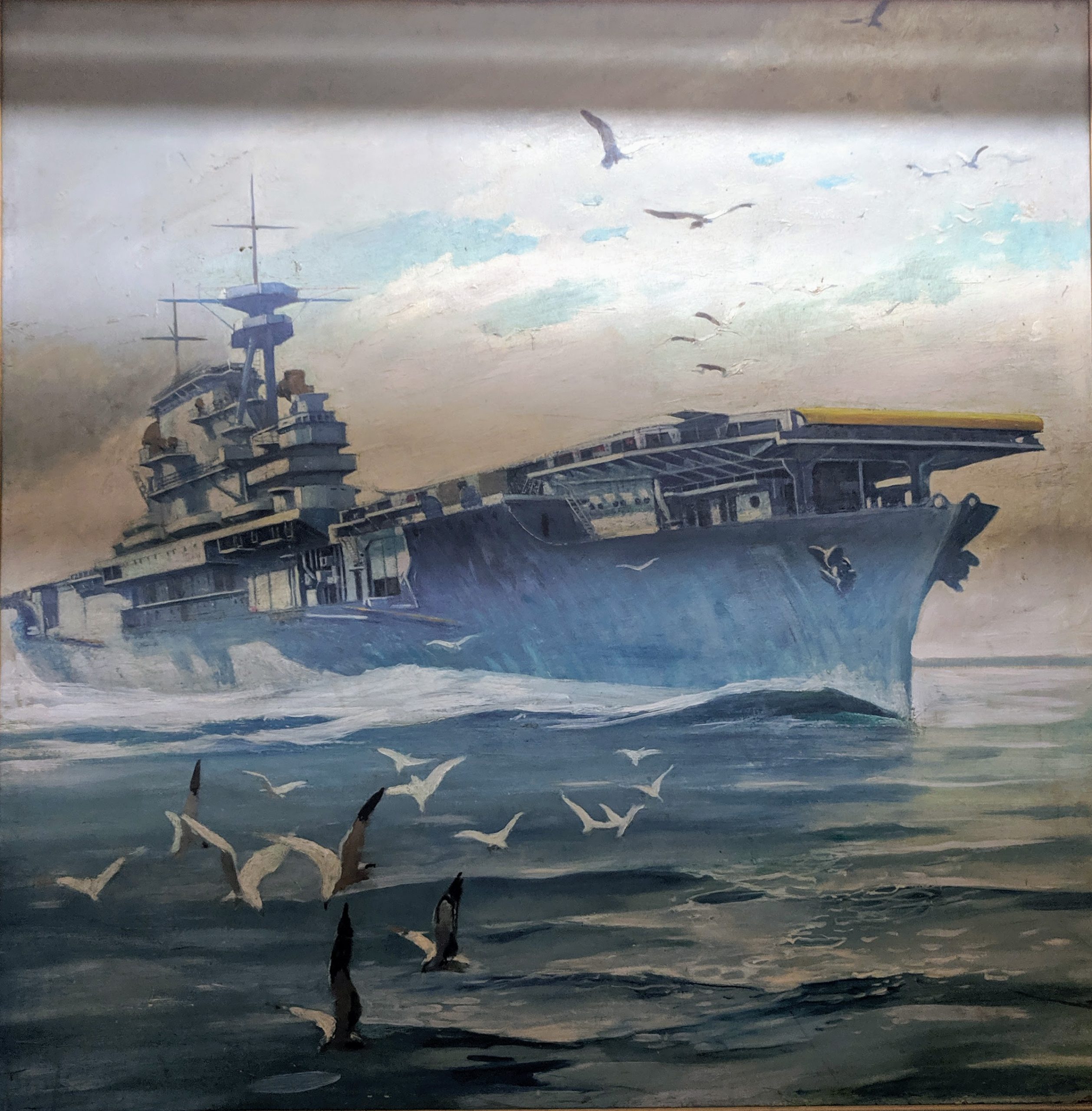

He was not only documenting what he saw at the yard, he was also producing paintings of each type of aircraft carriers the yard built. His first and second of these paintings were of the first carrier completed, showing the USS Ranger shortly before her christening in June of 1934. Skinner created two different paintings so the Captain and Executive Officer could choose which one they wanted displayed on the ship. It took him only six weeks to do the preliminary sketches and complete both paintings, and they were stylistically very different. The one rejected by the officers had bold colors, a more industrial look and more focus on the shipyard workers and equipment in the foreground. The other was a more romantic depiction of the ship with a delicate, but still accurate view as fog partially obscuring the pier and the workers. Shipyard workers created a gold painted wooden frame for the painting that had corners carved to look like rope and the wood stamped with the Naval Aviation and Naval Observation insignia. Skinner’s ‘rejected’ painting of the Ranger was put in the museum’s collection in 1934.

It is easy to imagine Skinner developing a fondness for each of the ships as he watched them being built, launched, christened, and then sent out to sea. Possibly even feeling like he shared a small part in their creation. But during World War II, he saw some of those ships leave and never return. Skinner’s 1937 painting of the USS Yorktown shows the aircraft carrier in her full glory, plowing through the waves. The ship was lost during the Battle of Midway in 1942.

The same thing would happen to some of the workers he stood beside, spoke to, and painted. Men like him, who sometimes carried a bottle of beer to work in their lunch bag to help beat the oppressive heat in the yard. In 1947 Skinner created his Memorial Mural, a three panel, 23 foot long and 6 foot high painting dedicated to the 28 shipyard apprentices who lost their life during WWII. Battle scenes take up a large portion of the mural, but the right side depicts a soldier mourning a flag-covered coffin and the left side features a young apprentice amid his tools, holding his draft notice and looking out into the yard. The names of the 28 apprentices are included on the mural.

Although he would still do other types of work like portraits and some nursery rhyme wall murals for a children’s nursery on a passenger liner, Skinner had become known both locally and beyond as a prominent and very talented maritime artist. Locally, his works were featured in the museum, in shipyard ceremony programs and on the cover of shipyard and apprentice school publications. Nationally, they appeared in newspapers, magazine articles and books. When the museum decided to create prints of some of his paintings and drawings to sell in the gift shop, these versions of his artwork found their way around the globe and some still turn up in auctions today.

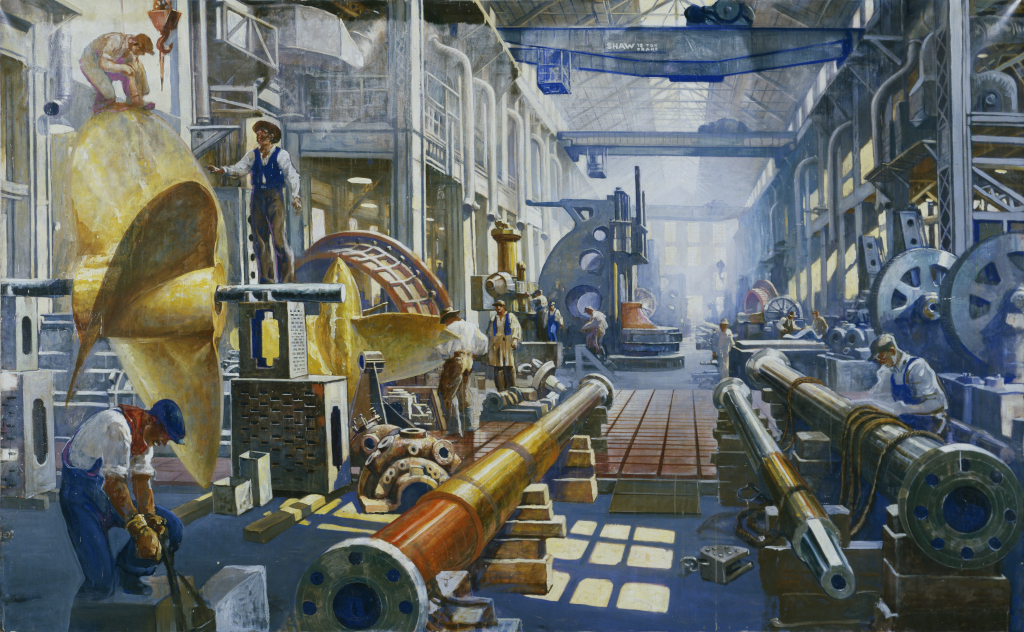

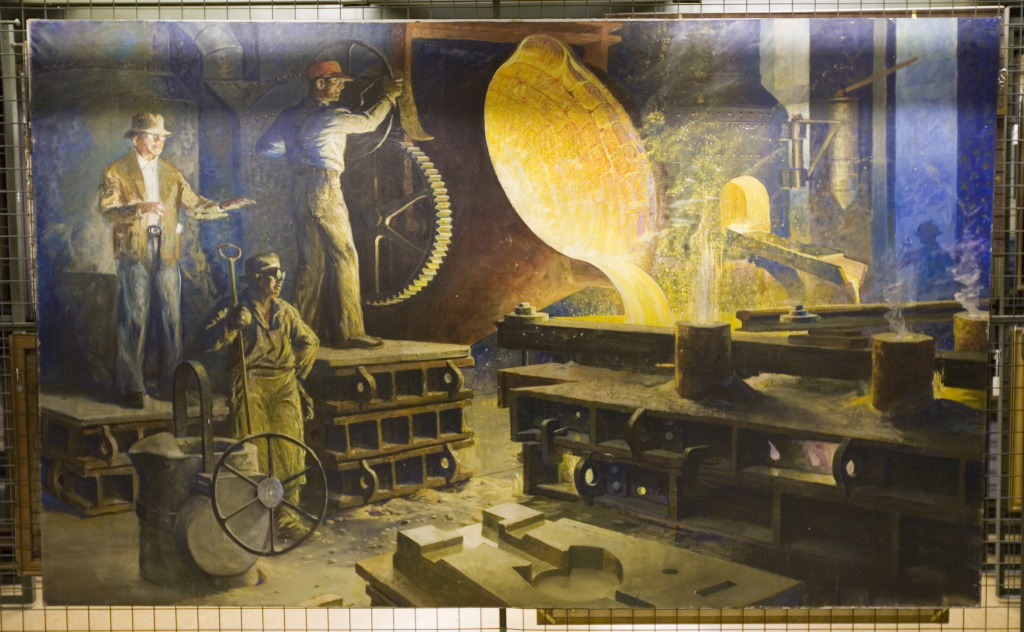

For the museum, Skinner also created a series of large, colorful murals that give an unprecedented look at the shipyard in the 1930s and its workers. The 14 paintings range between 10 and 12 feet long and slightly over 6-1/2 feet tall. The bright color and layers of paint Skinner used for texture and depth give these works a gritty and honest look, showing the sweat, straining, and the power of the shipyard and the builders. Skinner’s depiction of the shipyard’s 50,000 square foot Machine Shop shows the space full of immense tools like lathes and drill presses and boring machines. A perfect example of why the shop was considered the largest, most expensive, and best equipped shop of its kind in the country. His depiction of the shipyard foundry looks so realistic, the viewer expects to feel the heat of the molten metal being poured in the molds.

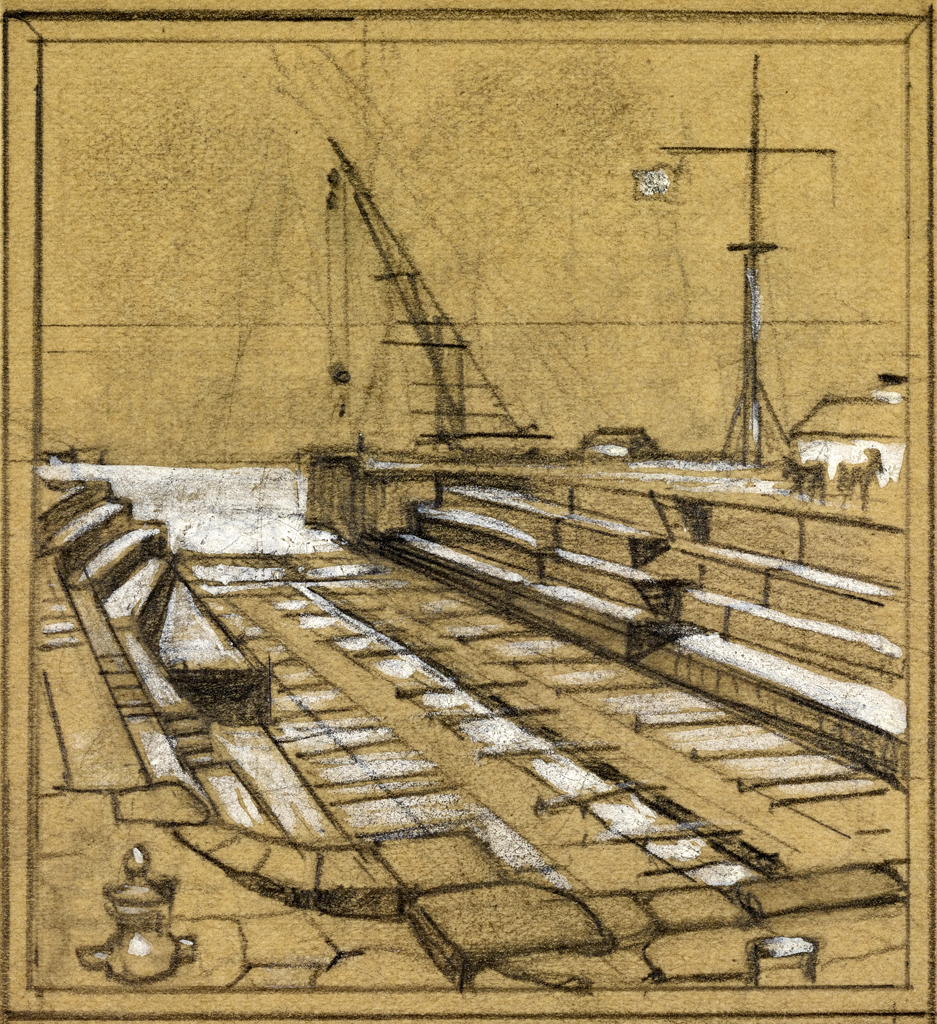

Also in the museum’s collection are 51 tiny pencil sketches on simple brown paper that Skinner may have used to experiment with potential subjects, line placements, shading and highlighting before he created the larger works. The smallest of these sketches measures about 2 inches wide and 2 inches high and the largest is about 5-1/2 inches long and 2 inches high. Despite their tiny sizes, each is meticulously executed and incredibly detailed.

Outside the Shipyard

Skinner appears to have been a modest or very private individual, or perhaps both. All accounts of him speak highly of his artistic talent and his individual works, but little else. Newspaper articles about his brother who was a local lawyer and his sister Mrs. Homer Ferguson sometimes included a few tidbits of information about him or his childhood. And occasionally there were society column briefs that stated Skinner and his wife were traveling or hosting various relatives at their home. His obituary, where one would expect to read all his accolades, was also very succinct. And no information could be found that stated how long he worked at the yard. But it does appear that Skinner was actively painting right up until his death in 1955 at the age of 66.

Perhaps it is more fitting that Skinner’s works are his accolades and speak for him. That they describe him best. The individual brushstrokes and the pencil lines that offer a view through his eyes of a shipyard, men, and wartime loss. The areas on his paintings where he put thick layers of paint to suggest a weathered beam or worn wood. The grit, the sounds and the smells in our imaginations, and the ships. The museum’s first, and only, staff artist during our 90 year history left an incredible legacy that has been enjoyed since we opened and will continue be enjoyed and appreciated by researchers and visitors far into the future. A legacy that allows us to celebrate our shipbuilding past and the shipbuilders that made it possible.

Thank you for being part of our 90 years and thanks for reading.