On June 28, 1861, the Union’s first charge of Confederate piracy since the Civil War erupted took place in the Potomac River when the passenger steamer St. Nicholas was captured. Captain George Hollins developed a daring scheme to capture the ship. Using the flamboyant Lt. Colonel Richard Thomas Zarvona masquerading as Madame La Force, the ship was taken over by the Confederates and used to capture three other Union merchant ships. Hollins and Zarvona were proclaimed vicious pirates in the North and treated like heroes throughout the South.

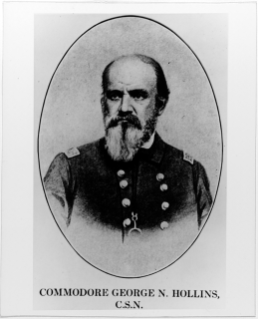

THE DARING VETERAN: CAPTAIN GEORGE HOLLINS, CSN

George Hollins was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on September 20, 1799. His uncle was Major General Samuel Smith, a hero of Baltimore’s defense during the British attack in September 1814. Smith arranged his nephew’s appointment as a midshipman that very same year. Hollins was first detailed to the sloop USS Erie. When Erie failed to escape the British blockade at the Chesapeake Capes, Hollins transferred to the frigate USS President, commanded by Commodore Stephen Decatur.

Decatur attempted to break out from New York with his squadron up the Long Island Sound in January 1815. During a heavy snowstorm, President ran aground and was captured by several British warships. Hollins was a POW in Bermuda with Decatur. The midshipman then served again with the commodore during the Second Barbary War on Decatur’s flagship, USS Guerriere.

On June 17, 1815, Decatur’s squadron encountered an Algerian squadron commanded by the infamous pirate Rais Hamidou. After two broadsides from the American frigate, Hamidou was killed and his ship surrendered. As the enemy’s deck was being cleared, Decatur picked up the pirate commander’s scimitar and gave it to Hollins for his gallant conduct.

Hollins continued his career serving later ships including Columbus, Franklin, and Washington; and was promoted lieutenant in 1828, commander in 1841, and captain in 1855. While in command of USS Cyane off Nicaragua’s Mosquito Coast, he bombarded and destroyed Greytown. This action was taken because the town’s citizens had damaged American property and injured the American consul there. His actions were cheered throughout the United States.

Hollins was detailed to command Sackett’s Harbor Navy Yard. He then took command of the sidewheeler Susquehanna in the Mediterranean Sea. When he learned of the Civil War’s outbreak on May 15, 1861, he steamed his ship back to Boston where he resigned his commission. However, it was not accepted by the US Navy and he was ordered arrested. Nevertheless, Hollins escaped to Baltimore.

THE ADVENTURER: LT. COL. RICHARD THOMAS ZARVONA

Richard Thomas Jr. was born on October 27, 1833, at his family’s plantation, “Mattapany,” on the Patuxent River in southern Maryland. His father, Richard Thomas Sr., was the former speaker of Maryland’s House of Delegates. His uncle, James Thomas, was a governor of Maryland. Richard Jr. was “most spirited and daring…a hard-riding and hard drinking young blade. An excellent sailor, marksman and skilled horseman,” [i]Richard was an elite of the elite gentry.1 He attended Charlotte Hall Academy and Oxford Academy in Maryland as well as the United States Military Academy in 1850. He left after one year, and then rumors and legends persist that he went to California to survey government lands.

His next supposed stop was China during the Taiping Rebellion. It was said that he fought pirates with the Ever Victorious Army. He soon became extremely enthralled by the exploits of Giuseppe Garibaldi during the Uruguayan Civil War and the wars for Italy’s unification. It appears that Garibaldi and other revolutionaries exuberated him with militant idealism, driving him to become a soldier of fortune.

Lviv National Art Gallery. Public Domain.

Thomas went to Italy in 1859 to join Garibaldi’s Red-shirts; instead, he became a lieutenant in the Imperial Zouaves during the French invasion of Italy. The Second Italian War of Independence was fought between the French Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It is believed that Thomas served in combat and was a witness to King Victor Emmanuel II’s triumphant entry into Naples. While serving in the Imperial Zouaves, Richard Thomas fell in love with a French lady who later died in his arms. He mourned her forevermore, even changing his name, in her honor, to Richard Thomas Zarvona.

A PLOT IS FORGED

Richard Thomas Zarvona returned to Maryland with the romantic notion that he sought to translate into reality via service with the Confederacy. As he wrote his cousin, “To avoid the fatigue of a private’s life – which I admit I am little prepared for, I wrote for information as to the means necessary to pursue a commission. … If Maryland raises a navy, will not someone be willing to fit out a small, strong, swift screw propeller vessel carrying 1 or 2 10 or 11 inch guns? As for men I think that I could get 150 in one day.” 2

In May 1861, Zarvona set up a camp of instruction at the mouth of the Coan River with 50 men to form the Zarvona Zouaves. While there, he began to dream how to capture the Potomac Flotilla warship, USS Pawnee, the exact type of vessel Zarvona wanted to use to terrorize the Chesapeake. The soldier of fortune then went to Richmond to meet with Governor John Letcher. When Zarvona arrived at the meeting it was said that he was “dressed in the height of fashion … fragile in form, with sharp irregular features, sharp indentations in his checks, blue eyes. … There was a deep-seated melancholy about the man.“ 3

During the meeting, Letcher thought that Zarvona was somewhat eccentric; nevertheless, he saw some merit to the plan. The governor, after conferring with the famous “Pathfinder of the Seas,” Mathew Fontaine Maury, promoted Zarvona to lieutenant colonel and gave him a $1,000 draft to execute his scheme.

THE PLOT THICKENS

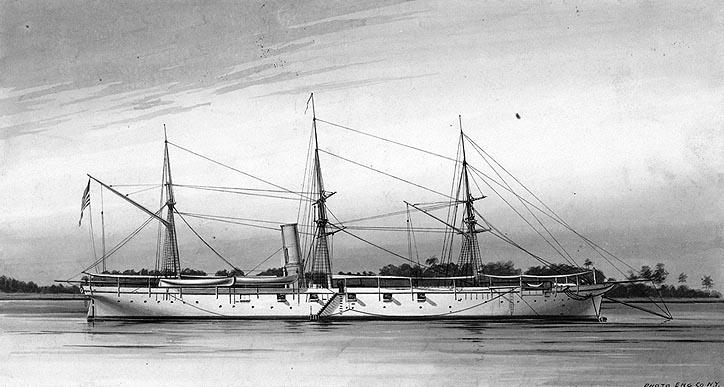

Zarvona then met with Commander Mathew Fontaine Maury and Captain George Hollins. They reviewed Zarvona’s concept and agreed that it could work. Hollins noted that a bay steamer needed to be captured. This would enable Hollins and his followers to use a ruse to come alongside to board and capture USS Pawnee. This screw gunboat was built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in 1859 and mounted 10 guns. It was then the flagship of the Potomac Squadron which also contained two smaller steamers, Thomas Freeborn and Reliance. This squadron was to stop smuggling from Maryland across to Virginia. Washington, D.C. was blockaded at this time by Confederate batteries at Mathias Point, Virginia. No supplies could reach D.C. via the Potomac River. The Union’s hope was that these gunboats could silence and capture these batteries and open the door to the federal capital.

The plans entailed that Zarvona would go to Baltimore and purchase weapons and recruit men for the venture. They would then book passage on board the steamer St. Nicholas. This packet boat had a regular run from Baltimore to Washington, D.C. with stops at various landings to pick up goods and passengers. Meanwhile, Hollins was to secure a group of Confederate naval officers and engineers to meet the plotters along the trip. Once all were aboard, they would take St. Nicholas by surprise. The Confederates were then to pick soldiers from the 1st Tennessee under the overall command of Brigadier General Theophilus Holmes. Once reinforced, the Confederates would use some type of trick to capture Pawnee.

Zarvona then went to Baltimore where he acquired cutlasses, carbines, and revolvers. He also recruited 15 volunteers. He found many willing Southern sympathizers, including George W. Alexander and George Watts. Watts later recounted that the news of Zarvona’s desperate mission leaked about the city. Watts volunteered; however, “I was mighty disappointed with the Colonel. He looked like one of those slick floor walkers in a department store. I think that the other men felt the same as I did but soon, we found we were all fooled. Believe me, Sir, that man had the quickest brain I ever came across, and his eyes were just as quick. Eyes? Why, when that man looked at you, they went right through you. It didn’t take us long to learn who was the boss around here.”.4

Zarvona advised his 16 followers that they would meet, all wearing disguises, and behave as if they were unknown to each other. They would travel south on the steamer St. Nicholas. Weapons would be waiting for them when the word was given to take over the ship.

THE FRENCH LADY

On the evening of June 28, 1861, about 60 passengers booked their passage, including a very stylishly dressed young lady speaking only broken English with a thick French accent. Her heavily bearded “brother” (George W. Alexander) helped translate her wishes. Her name was Madame LaForce. She had several heavy, large trunks with her that were going to help her start a millinery business in Washington. Entranced by her smile, the purser assigned her to a commodious stateroom off the main deck and had the deck hands haul her trunks into her cabin.

When the steamer departed Baltimore, she emerged from her stateroom and flirted shamelessly with the most attractive males amongst the passengers and ship’s officers. Captain Jacob Kirwin, the master of St. Nicholas, prided himself in his knowledge of French, so he tried out his vocabulary with the lady. According to George Alexander, “she proved herself quite a French native with a stream of coquettish language that overwhelmed him. Fluent French gushed from her lips. She radiated charm. A veil covered her eyes and cheeks, but not her reddened lips. She tossed her fan about and cocked her head at an angle toward any gentleman who occupied her attention at the moment. She meandered from salon to dance hall, flirting as she went with the ship’s officers.”

Captain Kirwin was upset: “I didn’t like the appearance of that French woman at all. She sat right next to me at dinner and so close that our legs touched. I thought she looked mighty queer. …That young woman behaved so scandalously that all the other women on the boat were in a terrible state.” It was said that one crew member, utterly mesmerized by the lady, leaned over to kiss her but straightened up abruptly with the mark of a hand slap on his cheek.5

St. Nicholas continued its run toward the Potomac. About midnight, several men, including an elderly gentleman with a cane, came on board at Point Lookout, Maryland. By this time, George Watts noted that none of the volunteers acted as if they knew each other: “But what worried me was that I couldn’t find the colonel or anyone who looked like him. I could see the failure of the whole expedition and I could also see myself behind bars at Fort McHenry. The picture didn’t look good to me. I was on deck wondering where it was all going to end and whether I’d be hung as a Rebel spy when someone touched me on the arm. I whirled about like someone had stuck a knife in me and saw Alexander. He grinned all the way that he had scared me and said, ‘You’re wanted in the second cabin.’ I hurried below and nearly had a fit when I found all our boys gathered about that frisky French lady. She looked at me as I came in — Lord, I knew those eyes in a minute! It was the colonel. He then shed his bonnet, wig, and dress and stepped forth in a brilliant new Zouave uniform.” 6 The men quickly opened the trunks and found them loaded with weapons. They buckled them on and went up to the main deck.

THE PLOT UNFOLDS

As Zarvona’s men raced onto the deck, the old man with a cane slipped off his wig and it was none other than Capt. George Hollins, who took over command of St. Nicholas. He steamed the ship to the mouth of the Coan River on Virginia’s side of the Potomac where they picked up about 30 Tennessee infantrymen. With these reinforcements, Hollins headed up the Potomac in search of the 10-gun USS Pawnee. This gunboat had already returned to Washington.

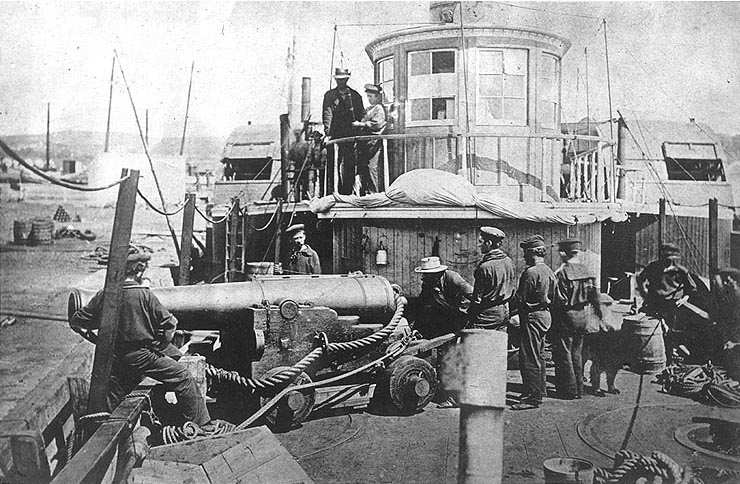

The Photographic History of The Civil War in Ten Volumes: Volume Six, The Navies. The Review of Reviews Co., New York. 1911. Ward was the first officer of USN killed during the War.

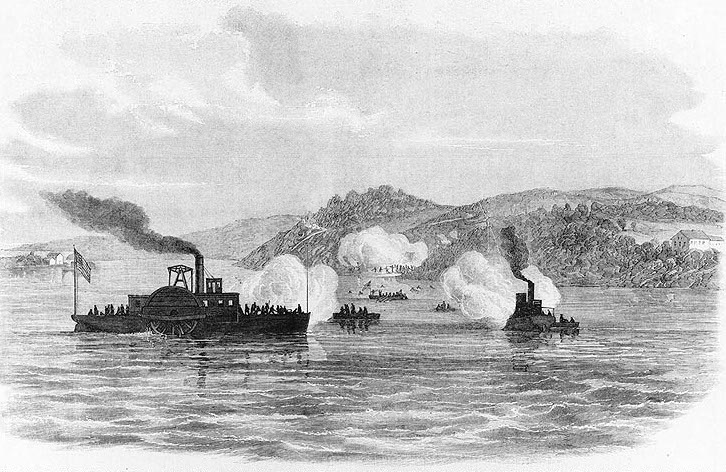

The other vessels of the Potomac Flotilla had attempted to capture the Confederate water batteries commanded by Colonel Daniel Ruggles at Mathias Point, Virginia. These batteries blocked Washington, D.C. from receiving any supplies or reinforcements by way of the Potomac River. The squadron’s leader, Commander James Harman Ward of USS Thomas Freeborn, had sent two landing parties that had been repulsed.

As Ward was sighting a shell gun to cover the Union withdrawal, he was mortally wounded by a sniper. Ward’s death prompted both USS Thomas Freeborn and USS Reliance to return to Washington so that Ward could have a state funeral.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 59242.

THE PREY HAD VANISHED BUT NEW VICTIMS FOUND

St. Nicholas searched for these Union warships without success. Hollins realized that the missing steamer would soon be discovered by Unionists and an overwhelming force would try to recapture the ship. He took St. Nicholas out of the Potomac and into the Chesapeake Bay. The Confederates chanced upon a large brig, Monticello, loaded with 35,000 bags of coffee, headed from Brazil to Baltimore. Hollins sent this ship up the Rappahannock River to Fredericksburg.

One hour later, St. Nicholas took the schooner Mary Pierce, filled with ice. Lieutenant Robert D. Minor was placed in command of this vessel and he sailed it to Fredericksburg. The steamer was by now running low on coal; however, the coaling schooner Margaret was then luckily captured. Hollins coaled his ship and then towed Margaret to Fredericksburg. St. Nicholas was later commissioned into Confederate service as CSS Rappahannock.

A HERO’S WELCOME

When Hollins and Zarvona reached Fredericksburg, a ball was given in their honor. They then moved on to Richmond where even more celebrations were held. George Watts noted that Zarvona presented a “dramatic illusion of oriental splendor, blue pantaloons, embroidered vest, white gaiters, crimson cloth with gold tassel and a light beautifully crafted sword.”7 One British observer saw Zarvona at the Spotswood Hotel in Richmond, noting what “a strange man he was as he walked into a dining room in his Zouave costume and red cap on his closely shaved head. The tassel hung low down on his shoulders … and his manner was silent, reserved and gloomy. Poor Man!”8

FADED GLORY

George Hollins was promoted shortly after the capture of St. Nicholas to flag officer and sent to New Orleans to command the Confederate naval forces. He gained additional laurels with his October 11, 1861, victory during the Battle of the Head of Passes.

Richard Thomas Zarvona was not as fortunate. Even though Zarvona was called a great hero throughout the South, he was labeled a pirate in the North. Federal forces in Maryland were on the lookout for the “French Lady’s” next exploit. Zarvona endeavored to take over the bay steamer Mary Washington; however, he was captured on July 9, 1861, when the steamer reached the dock at Fort McHenry.

There was talk of hanging Col. Zarvona as a pirate; instead, he was imprisoned at Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor. He suffered greatly in his close confinement there and was ultimately exchanged in April 1863. By this time, Zarvona was suffering from a severe nervous condition and went to Europe to regain his health. When he finally returned to Maryland, he was beset by poor health and financial difficulties and was forced to live with his brother, James William Thomas. Zarvona died at his brother’s home known as “Great Falls” near Chaptico, Maryland. on March 17, 1875.

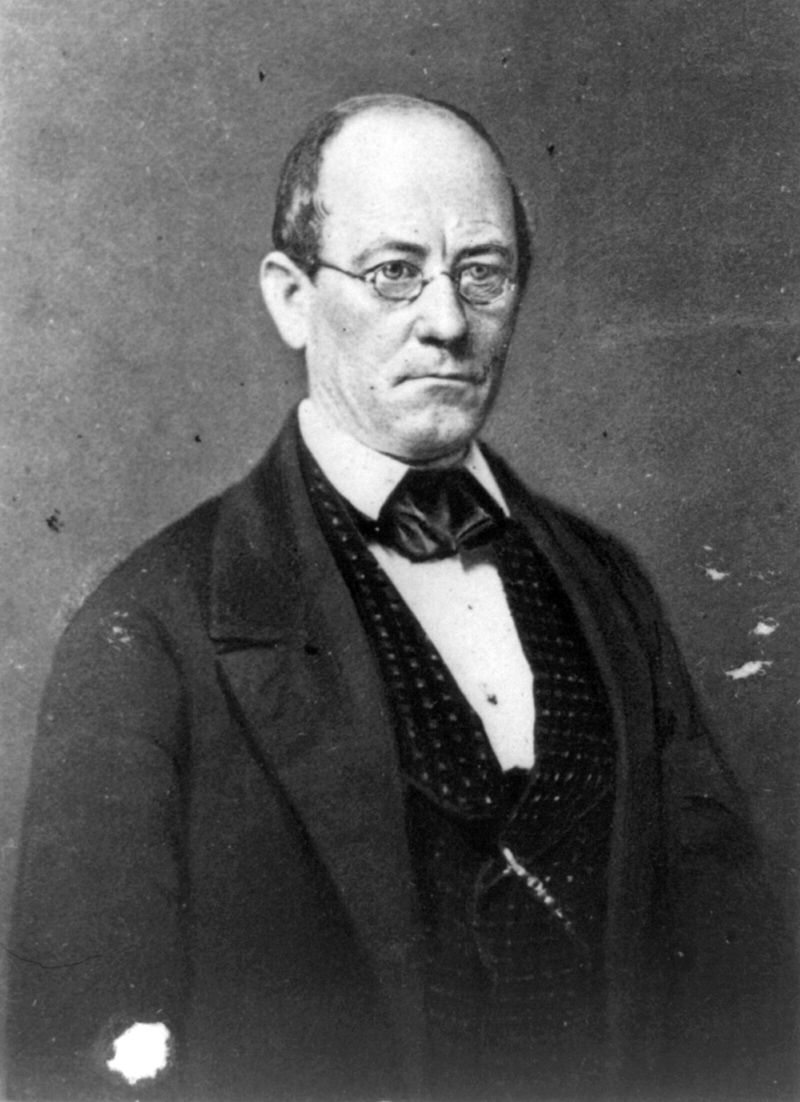

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division.

Governor John Letcher of Virginia wrote a memorial in the colonel’s honor: “Colonel Zarvona was a most extraordinary man. … If any man has ever lived of whom it must be said ‘he was insensible to fear,’ Zarvona was undoubtedly that man. He … sought the most hazardous undertakings, and fearlessly exposed himself to the most formidable dangers. And yet modesty, candor, and sincerity … were predominant traits in his character. He was … a true and tried citizen, and a patriot and gallant soldier. He was somewhat eccentric, but his eccentricities did not render him disagreeable; on the contrary, tended to inspire regard for and excite interest in him.”9

Notes

- Armstrong Thomas. The Thomas Brothers of Mattapany. Manuscript, n.d. Library of Congress.

- ibid.

- “Richard Thomas Zarvona.” Civil War Notes, n.d. The Latin Library. Accessed July 2, 2020; http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/chron/civilwarnotes/zarvona.html.

- “Last Survivor of a Gallant Band.” The Evening Sun (Baltimore, MD), August 27, 1910.

- “Richard Thomas Zarvona,” The Latin Library.

- “Last Survivor of a Gallant Band.” Evening Sun.

- ibid.

- Armstrong Thomas. The Thomas Brothers.

- ibid.

Bibliography

Bennett, J.L. “The French Lady: A Most Agreeable Gentleman.” Abbeville Institute. The Abbeville Blog, March 28. 2019. Accessed July 10, 2020. https://www.abbevilleinstitute.org/blog/the-french-lady-a-most-agreeable- gentleman/

Cox, Richard P. “Rebel raider disguised in a hoop skirt.” The Washington Times, October 6, 2007.

Holly, David C. The Chesapeake Corsair. Centreville, MD: Tidewater Publishers, 1994.

Official Records of the Union and Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series 1, Volume 4. Washington, DC.