Did the crew of USS Monitor hear “Taps” when it was played for the very first time?

I will attempt to answer this question, but you may be wondering why I asked it in the first place. It all started with a bugle and a memorial service for my father. I will come back to the memorial service in a moment, but first let me show you the bugle that drew my attention.

This bugle from the Spanish Cruiser Vizcaya is on display in our Defending the Seas gallery. Vizcaya was sunk in 1898 during the Battle of Santiago, Cuba in the Spanish-American War. The bugle was recovered from the wreckage.

What was a bugle doing in a maritime museum, I asked? To some of you it may be obvious, but I had a lot of learning to do. Please come along with me on my journey from this bugle and my father’s memorial service to the bulge call we know as “Taps” and the crew of USS Monitor.

Bugle calls are musical signals that announce scheduled and certain non-scheduled events. They were also used in battle. We often associate bugle calls with the Army, but bugle calls were used on nineteenth century warships. The call below is found in the records of USS North Carolina and USS Columbus from 1825.

Commodore’s Dinner Call

That explains why we have a bugle at a maritime museum, but what about”Taps” and the crew of USS Monitor?

Let’s return to USS Columbus for a moment. USS Columbus was sent to California during the Mexican-American War in 1847, but she proved to be too large to be useful because of the lack of deep water ports in California. Columbus was sent back to the east coast and arrived in Norfolk on March 2, 1847. She stayed at the Norfolk Navy Yard, what became the Gosport Navy Yard, “in ordinary,” basically mothballed, until April 20, 1861. On that date, the Gosport Navy Yard was burned by exiting Union troops.

This was the same fire that burned USS Merrimack. Merrimack was only burned to the waterline, so the hull and the ship’s engine were salvageable and were used by the Confederacy to produce CSS Virginia. It was CSS Virginia that fought USS Monitor on March 9, 1862 – the very first battle between ironclads. USS Monitor remained in the James River throughout the summer of 1862.

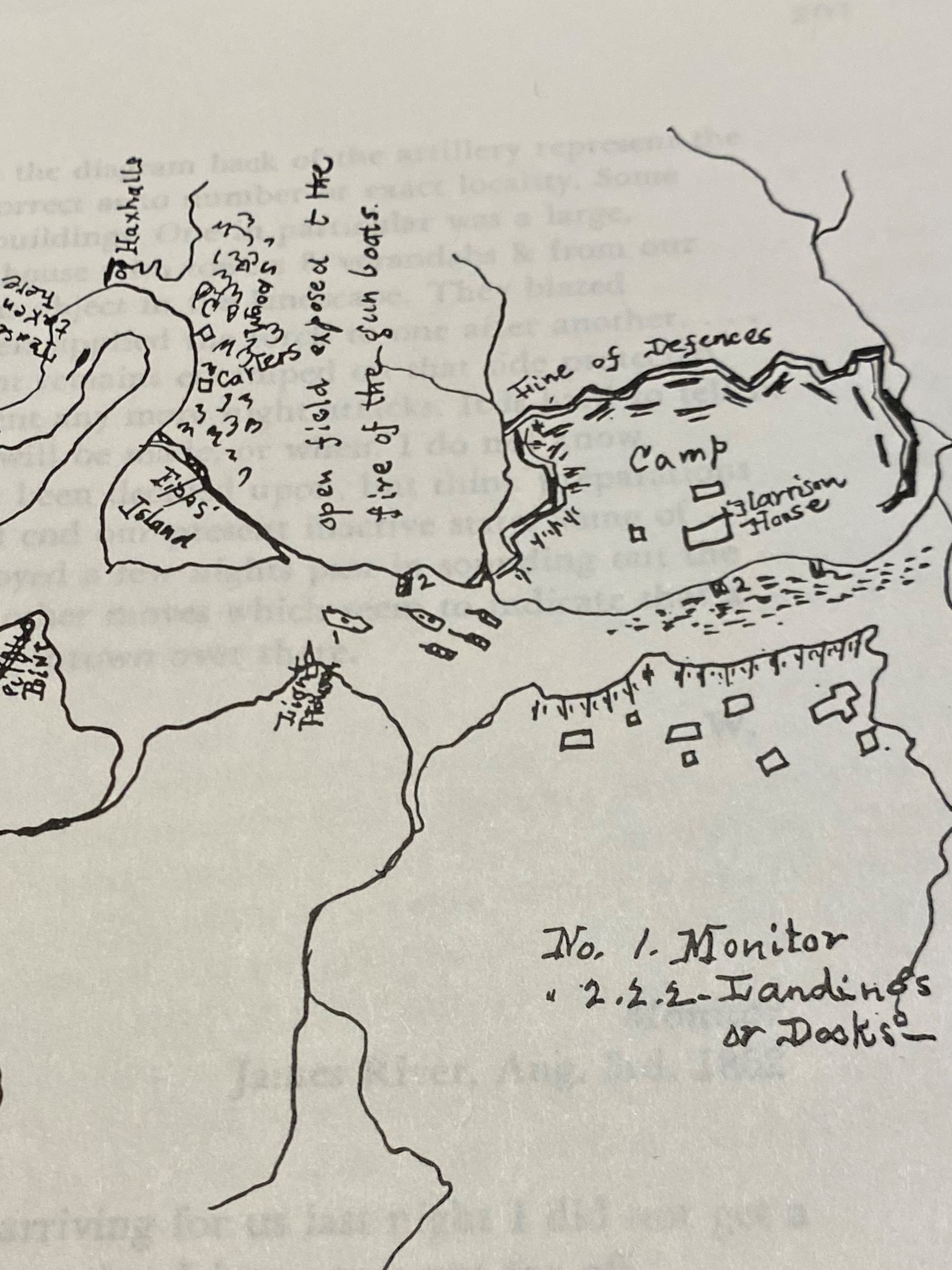

The Army of the Potomac launched a campaign to capture Richmond, Virginia during the summer of 1862. The campaign ended with the Seven Days Battle. At the end of this battle, Union troops under General George McClellan camped at Harrison’s Landing on the James River. USS Monitor was also at Harrison’s Landing. We have letters from two of the Monitor crew. Below are excerpts from their letters.

William Keeler, USS Monitor Acting Paymaster, to his wife Anna

July 2, 1862

“8 o’clock P.M. At anchor on Harrison’s bar. A city of tents ashore stretching for miles along the river & way back as far as we can see, through woods & openings, over corn & wheat fields are tents & soldiers.”

William Keeler

July 3, 1862

“In the very center of the camp stands Mr. Harrison’s fine residence. His large fields of wheat & corn so green & promising the day before are now beat hard & brown.”

William Keeler

July 14, 1862

“The building bears evident marks of age, the bricks of which it is constructed having been brought from England.It also has additional interest from having been the birth place of Pres’t Harrison.”

George Geer, USS Monitor Engineer Yeoman, to his wife Martha

July 15, 1862

“We are still laying at our Ancorage and there is no news. This place was the home of Wm. Henry Harrison, President of the U.S., and the house occupied by the Army was the one in which he was Born.”

William Keeler

August 1, 1862

This map was in William’s letter to Anna

We will leave the crew of Monitor at Harrison’s Landing for moment and return to my Father’s memorial service. He was a Korean War veteran, and it was incredibly special to have a group of veterans come to his memorial service to honor him. As part of the ceremony before “Taps” was played, one of the men read the history of this bugle call. Below is a copy of what he read.

“In 1862, Union Captain Robert Ellicombe was hunkered down with his men near Harrison’s Landing, Virginia. The Union army was being pressed by the Confederates after having been routed during the Seven Days Battles.

One night, Captain Ellicombe heard a wounded soldier moaning in the

no-man’s-land between the two armies. Risking his own life, the Captain moved out between the lines to carry the wounded man to safety. When he was finally back behind his own lines, Captain Ellicombe discovered that the young soldier he had carried was actually a Confederate and had died just as they reached the hospital tent.

Upon further inspection, the face of the Confederate soldier looked somewhat familiar. Suddenly, the Captain came to the shocking realization that the young man was his own son.

Consumed with grief, Captain Ellicombe asked to be able to bury his boy with military honors, but he was denied, because his son was a Confederate. However, he was allowed to have a bugler to play as his son was lowered into his grave.

When asked what he would like the bugler to play, the Captain provided a piece of paper that his son had been carrying. On the paper was written a series of twenty-four notes. It is said that this haunting scene was the first time that “Taps” was ever played.”

It is a lovely story, but it seemed too perfect to be believable. After some research, I found that the story was created by Robert Ripley for his Ripley’s Believe it or Not TV show in 1949! So now I had to find out what the true history of “Taps” really was. That brings us back to Harrison’s Landing.

After an article by Gustov Kobbe entitled “The Trumpet in Camp and Battle” was published in Century Magazine in 1898, a bugler by the name of Oliver Norton wrote to the editor of the magazine. Below are excerpts from Oliver Norton’s letter.

“General Daniel Butterfield, then commanding our Brigade, sent for me, and, showing me some notes on a staff written in pencil on the back of an envelope, asked me to sound them on my bugle. I did this several times playing the music as written. He changed it somewhat lengthening some notes and shortening others, but retaining the melody as he first gave it to me.

“After getting it to his satisfaction he directed me to sound that call for ‘Taps’ thereafter in place of the regulation call.

“The music was beautiful on that still summer night and was heard far beyond the limits of our brigade.

“The next day I was visited by several buglers from neighboring brigades asking for copies of the music, which I gladly furnished. I think no general order was issued from Army Headquarters authorizing the substitution of this for the regulation call, but as each brigade commander exercised his own discretion in such minor matters, the call was gradually taken up all through the Army of the Potomac.

After receiving Norton’s letter, the Century editor wrote to Daniel Butterfield. This is a portion of the letter he received from General Butterfield.

“The call of ‘Taps’ did not seem to be as smooth, melodious and musical as it should be, and I called in someone who could write music, and practiced a change in the call of ‘Taps’ until I had it to suit my ear, and then, as Norton writes, got it to my taste without being able to write music or knowing the technical name of any note, but, simply by ear, arranged it as Norton describes.”

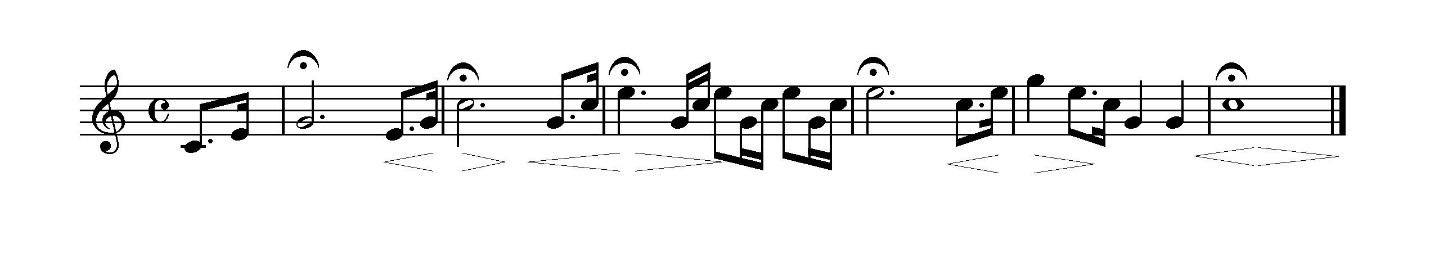

This was the version of “To Extinguish Lights” or “Taps” that was being used at the time.

To Extinguish Lights

General Butterfield said that he wanted a “smoother, more melodious and musical” “To Extinguish Lights” or “Taps.” It seems that General Butterfield was not composing a melody in Norton’s presence, but arranging or revising an existing one. He seems to have been revising the last six measures of the “Scott Tattoo” from a manual written by Winfield Scott that was in use from 1835 – 1860. A Tattoo was the bugle call notifying soldiers to assemble for the final roll call of the day.

Daniel Butterfield served as a regimental commander before the war and would have been familiar with this bugle call. All officers of the time were required to know the bugle calls and expected to be able to play the bugle. Below is the entire “Scott Tattoo.”

Scott Tattoo

In use from 1835 – 1860

Below are the last six and one-fourth measures of the “Scott Tattoo” and a copy of “Taps.”

Last six and one-fourth measures of the “Scott Tattoo.”

As a bugler during the Civil War, Oliver Norton most probably would have been playing another version of the Tattoo that came into use just before the war. It seems that Norton did not know the earlier Tattoo, the “Scott Tattoo,” or he would have recognized it that evening.

It looks like the “Taps” mystery is solved. General Butterfield never claimed credit for writing “Taps.” The event was not even recorded until the Century Magazine article appeared. That was 36 years after it happened.

Retired Master Sergeant Jari Villanueva is considered the country’s foremost authority on the bugle call “Taps.” Master Sergeant Villanueva served with the United States Air Force Band at Bolling Air Force Base in Washington, D.C. and was head of the 150th anniversary observance of the writing of “Taps” at Harrison’s Landing. In his book entitled 24 Notes that Tap Deep Emotions he writes:

“On a good clear night, the sound of a bugle will travel 1 or 2 miles away. So the other buglers heard it – and they picked it up right away.

Pretty soon everyone was playing “Taps” to signal ‘Lights Out’ – even the Confederates. It transcended the politics of the war and the conflict between North and South.”

Mr. Villanueva’s words bring us to the crew of USS Monitor. He reminds us that the sound of a bugle can travel one or two miles. We know from Oliver Norton’s letter that “Taps” was heard “far beyond the limits of our brigade.”

Did the crew of USS Monitor hear “Taps” when it was played for the very first time? I think it is definitely possible they heard it played soon after it started being used if they did not hear it played for the very first time. Both George Geer and William Keeler write from Harrison’s Landing on multiple days. George Geer writes from Harrison’s Landing as late as August 24, 1862. I would like to think that the crew of USS Monitor heard “Taps” played! Since we do not have a written record from anyone, I cannot say for sure. What do you think?

All of the recordings used in this blog were taken from the album Day is Done: 150th Anniversary of Taps and are used with permission from Jari Villanueva.