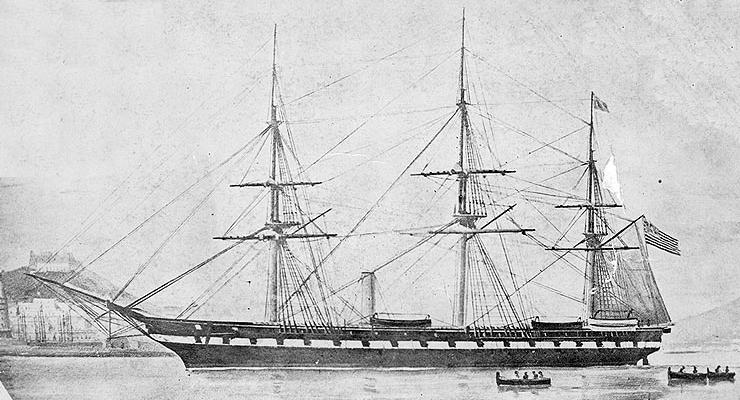

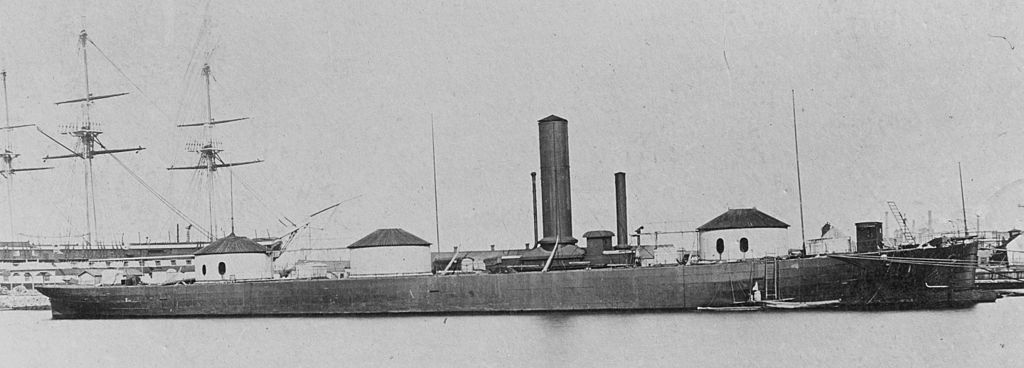

The USS Roanoke was a Merrimack-class steam screw frigate built at the Gosport Navy Yard. The frigate was commissioned in 1857 and became the flagship of the Home Squadron. When the Civil War erupted, Roanoke captured several blockade runners and fought during the March 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads. Noting how the Confederates had transformed Merrimack into the ironclad CSS Virginia, the wooden Roanoke was converted into an ironclad at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The new Roanoke featured three turrets; however, the extra weight of the iron made the vessel unstable and it spent the rest of the war in Hampton Roads, Virginia, and was scrapped in 1883.

A Novel Example of Naval Architecture

The USS Roanoke, named after the Roanoke River, was a Merrimack-class steam screw frigate. It was laid down at Gosport Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Virginia, in May 1854. When Roanoke was launched amidst a large cheering crowd, it immediately sank to the bottom of the Elizabeth River. The frigate had to be raised before it could be completed. [1]

USS Roanoke General Characteristics

Displacement: 4,472 tons.

Length: 263.8 ft.

Beam: 52.6 ft.

Draft: 23.9 ft.

Speed: 8.8 knots Steam/ 10.5 knots Sail only.

Machinery: 1 screw, 2 cylinder horizontal direct-acting trunk engine, 4 Martin boilers, 997 hp (The machinery was constructed at Tredegar Iron Works, Richmond, Virginia.)

Compliment: 674 officers and men.

Armament: 1 x X-inch Dahlgren pivot gun

2 x 12-pounder smoothbore howitzers

14 x VIII-inch Dahlgren shell guns

28 x IX-inch Dahlgren shell guns.[2]

(This frigate had a powerful battery ship for the 1850s. The X-inch Dahlgren pivot gun had a range of 3,000 yards using a 103-pound shell. The 28 IX-inch shell guns could fire a 72.5- pound shell 2,300 yards, and the other 14 VIII-inch Dahlgren’s could fire a 51.5-pound shell 2,300 yards.)[3]

Propulsion System

The Roanoke was a rather well armed warship as were most of the Merrimack-class. Likewise, these frigates were designed for sailing with the engine systems installed only for going in and out of port as well as for maneuvering during battle. John Lenthall, chief, US Navy Bureau of Naval Construction, had designed the ship with a sheer hull to enable the frigate to make its maximum speed while operating only under sail. This made this class of frigates gun platforms unstable in heavy seas.[4]

The Roanoke could unfurl 48,757 feet of canvas. The engine could only produce 869 HP at the propeller shaft. The engines required 103 HP to start, and when all this power was delivered to the segmented propeller shaft, 65 HP was lost from the friction of the shaft mounted on unstable supports. Perhaps Roanoke’s most notable feature was the use of a screw propeller which enabled all the machinery to be installed beneath the water line providing the engine with some protection from enemy fire. The Roanoke’s propeller was a two-blade bronze screw with a spherical hub designed by Robert Griffiths.

This concept endeavored to enhance engine power while also operating under sail. Griffiths’ idea featured a narrow blade design and fitted the propeller in its socket with an automatic pitch gear to increase the pitch as the velocity increased. When operating under steam, the propeller was set at thirty-six degrees. The blades would be set at zero and locked vertically behind the stern post to reduce drag for operations under sail. In addition to the locking device, Merrimack-class frigates were fitted with a bronze frame hoist system called a banjo. This allowed the propeller to be hauled out of the water for maintenance. As further proof that Lenthall preferred sail power, he made the funnel telescopic, which allowed the smoke pipe to be lowered when the engine was not in use, lessening the drag.[5]

Into Service

The USS Roanoke was commissioned on May 4, 1857. Captain John B. Montgomery was named captain of one of most modern ships in the US Navy. Montgomery had joined the US Navy at the start of the War of 1812, His most distinguished service was during the September 10, 1813 Battle of Lake Erie. His gallant service aboard USS Niagara earned him a vote of thanks and a sword from Congress. Montgomery was promoted commander in 1839 and took command of the sloop of war USS Portsmouth in 1844 as part of the Pacific Squadron. When the Mexican War erupted, Portsmouth played a critical role in the capture of Yuena Buena (San Francisco) and operations along the Baja, California Gulf of California coast. [6]

The Roanoke was assigned as the flagship of the Home Squadron, Commodore Hiram Paulding commanding. The frigate was immediately sent to Aspinwall, Columbia (Colon, Panama, today), to transport the notorious filibuster, William Walker, back to the United States. William Walker had taken over as president of Nicaragua in 1856; however, was overthrown in 1857 and forced to flee. The Roanoke picked Walker up, under the direction of Commodore Hiram Paulding, and returned him to Hampton Roads, Virginia.[7] Then Roanoke was placed in ordinary at the Charleston Navy Yard on September 24, 1857. Placed back into service as flagship of the Home Squadron, the steamer was stationed at Aspinwall, Columbia, to await the arrival of the first Japanese delegation to the United States to sign the 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce. Eventually, Roanoke transported the Japanese contingent to Hampton Roads on May 12, 1860. Once again, the ship was soon decommissioned.[8]

The Civil War Erupts

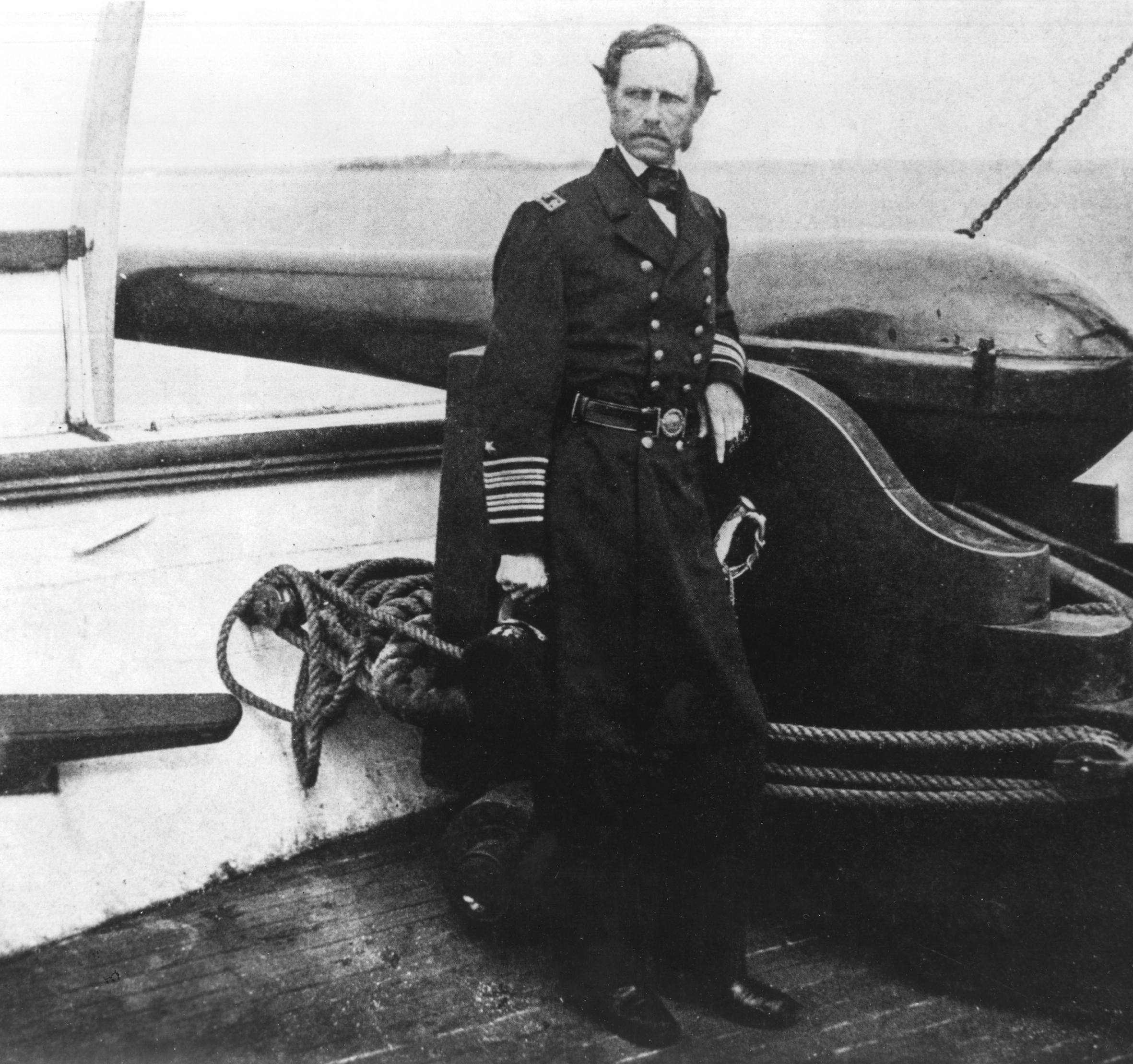

When the Civil War began, the US Navy especially needed all of its steamers available to help enforce the blockade. The Roanoke was recommissioned on June 20, 1861, and assigned to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. The frigate’s new commander was Captain John Marston. Marston had worked in the navy since the War of 1812. During his long service, he was able to meet former president John Adams, the Marquis de Lafayette, Lord Byron, and shipmates like Matthew Fontaine Maury. Just before the Civil War, Marston was the commandant of the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

The USS Roanoke began its cruise toward the southern coast in early July, destination Charleston, South Carolina. En route, the frigate captured the runner Mary off Lockwood Inlet, North Carolina, on July 13, and then captured Albion, Alert, and Thomas Watson off Charleston. [9] The Roanoke’s deep draft and troublesome engines prompted the vessel’s reassignment to Hampton Roads, Virginia, in November 1861.

Hampton Roads

As the new year dawned, Roanoke was stationed off Fort Monroe along with the capital ships steam screw frigate USS Minnesota (47 guns) and sailing frigate USS St. Lawrence (52 guns). Nearby, at Camp Butler on Newport News Point, were the sailing frigate USS Congress (50 guns) and sailing sloop of war USS Cumberland (24 guns). It appeared to be a powerful squadron however, each ship had several problems, especially Roanoke.

The Roanoke not only suffered from an acute shortage of veteran seamen, but the frigate also required major repairs. This steam screw frigate’s engine was useless due to a broken crankshaft. “When I think of this ship’s crippled condition–no engine and 180 of her crew deficient,” wrote Marston, “it makes me sick at heart.” [10] Seaman Joseph McDonald lamented, “We sailors couldn’t understand why the government would leave such a powerful ship in a condition like that.”[11]

All these warships were needed in Hampton Roads due to the ominous threat of the Confederate ram Merrimack (CSS Virginia) emerging from the Gosport Navy Yard. Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, had assembled these Union ships across the harbor from Norfolk, Virginia, in an effort to counter any possible threat from the Confederate ironclad.

Goldsborough, before leaving in mid-January for North Carolina to support Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside’s Roanoke Island, North Carolina, expedition, detailed Captain John Marston as acting commander of the Union naval units in Hampton Roads, His advice to Marston: confront the Confederate ironclad when it entered Hampton Roads by bringing all of his vessels together against the enemy warship. Goldsborough and Marston both knew that only by pounding the armor-clad with all the heavy guns of the squadron could the Union hope for any margin of success.

“Nothing I think,” wrote Goldsborough, “but very close work can be of service in accomplishing the destruction of the Merrimack and even of that a great deal may be necessary.”[12]

The Battle of Hampton Roads

News of the immediate attack of the Confederate ironclad continued to drift across Hampton Roads. Several armed tugs — USS Zouave, USS Young America, and Dragon — were positioned at Newport News Point and near Fort Monroe to tow the sailing ships at either position into action wherever they were needed. Everyone in the Union squadron was ready for the engagement and wished that Merrimack would finally make its attack. Marston wrote Gideon Welles, “I am anxiously expecting her and believe I am ready.”[13]

In the early afternoon of March 8, 1862, CSS Virginia finally emerged from the Elizabeth River and set a course for Newport News Point. When the Confederate ironclad was first seen by the Federals, “Suddenly, huge volumes of smoke began to pour from the funnels of the frigates Minnesota and Roanoke at Old Point,” Ashton Ramsay, chief engineer of CSS Virginia, recalled. “They had seen us and were getting up steam. Bright colored signal flags were run up the masts of all of the ships of the Federal fleet,” Ramsey continued.[14] Marston ordered the capital ships off Fort Monroe to move toward Newport News Point. The USS Minnesota, with the support of the armed tug USS Whitehall, ran aground off the Newport News Bar and was unable to free itself from the shoal.

The Roanoke was the next to try to reach the scene of the battle, helped by the armed tug USS Dragon. Marston, seeing where Minnesota had run hard aground, endeavored to take a wider path around Newport News Point. Unfortunately, the frigate ran onto Middle Ground shoal. Next came USS St. Lawrence, towed by USS Young America and USS Cambridge. They set a course between the two grounded ships and ran into the Newport News bar. Chaos reigned! Somehow, Roanoke was pulled off Middle Ground Shoal and returned to Old Point Comfort. Marston knew that his frigate might be the only warship able to stop Merrimack from entering the Chesapeake Bay and steam toward Washington, DC.

The burning USS Congress set an eerie glow across Hampton Roads when, like a miracle, the Union ironclad USS Monitor arrived and immediately reported to Captain John Marston as ordered. Marston had received several telegrams from Washington. First, on March 7, to send both Congress and Cumberland up the Potomac River. By the evening of March 8, both warships had been destroyed. The panic was so great in Washington that Marston had been ordered to detail the Union ironclad to defend the nation’s Capital. Marston realized that Monitor was the vessel that might be able to stop the Confederate ironclad from destroying the rest of the Union wooden warships the next morning.

When Lieutenant John Lorimer Worden came aboard Roanoke and met with Capt. Marston, Marston advised Worden of these orders from the Secretary of the Navy. He then rescinded them and ordered Lt. Worden to station his ship next to the stranded USS Minnesota to protect the frigate from Merrimack [15] The next day, Monitor did indeed save the Federal fleet and immediately, the US Navy considered how to build more ironclads.

A Counter to the Merrimack

The successes of both USS Monitor and CSS Virginia during the Battle of Hampton Roads enlightened both the North and South. They now knew they needed more ironclads, especially ocean types, if victory was to be achieved. Noting how USS Merrimack had been transformed into an ironclad, John Lenthall, chief of Construction and Repair, and Benjamin Isherwood, chief of Steam Engineering, believed that Roanoke should be transformed into an ocean-going ironclad. They had recognized that the re-configured Merrimack had strong shot-proof qualities, rifled guns that outperformed any Union naval gun in Hampton Roads, and the devastating effect of the ironclad’s ram. After all, Roanoke was a sister ship to Merrimack, so if the Confederates could turn a Merrimack-class frigate into an ironclad, the US Navy could do as well. Furthermore, Roanoke’s machinery required a complete overhaul and it would be cheaper to make this conversion rather than building a keel-up sea-going ironclad. Accordingly, they made a recommendation to Secretary Gideon Welles that this project be undertaken. The Secretary of the Navy accepted the proposal.[16]

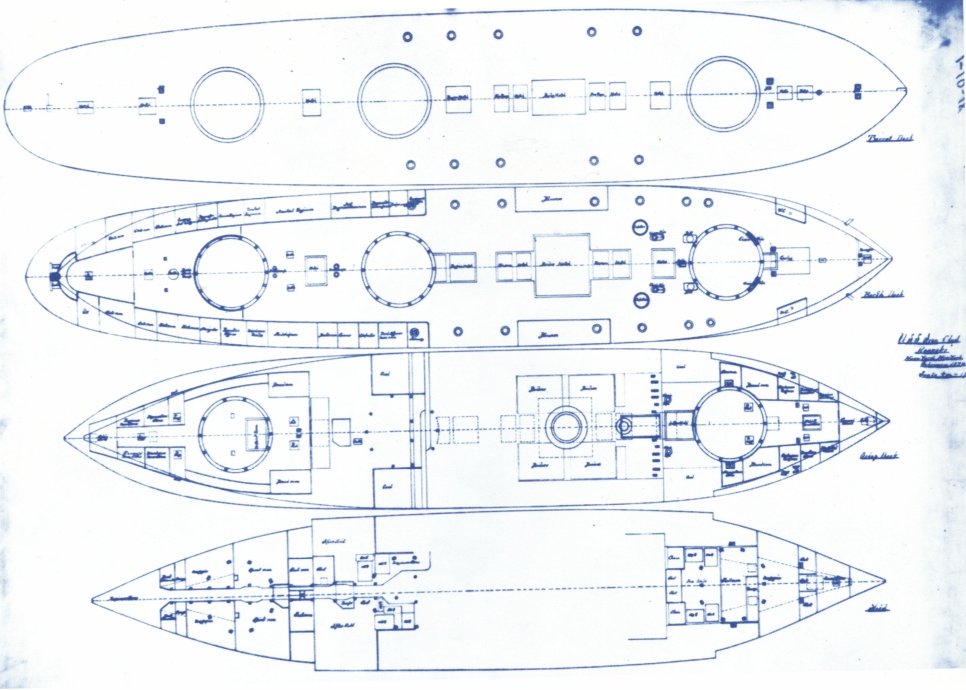

Reconfiguring the Roanoke

The USS Roanoke arrived at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on March 25, 1862. Work immediately began transforming the old frigate into an ironclad. The yard removed the warship’s masts, rigging, and everything else above the upper deck except for the funnel. An additional boiler was installed to operate the turret engines. The vessel was cut-down to its gun deck. The hoisting screw was removed, and a smaller propeller was installed. Novelty Iron works of New York City received the contract to fabricate, shape, and install all of Roanoke’s ironwork.[17]

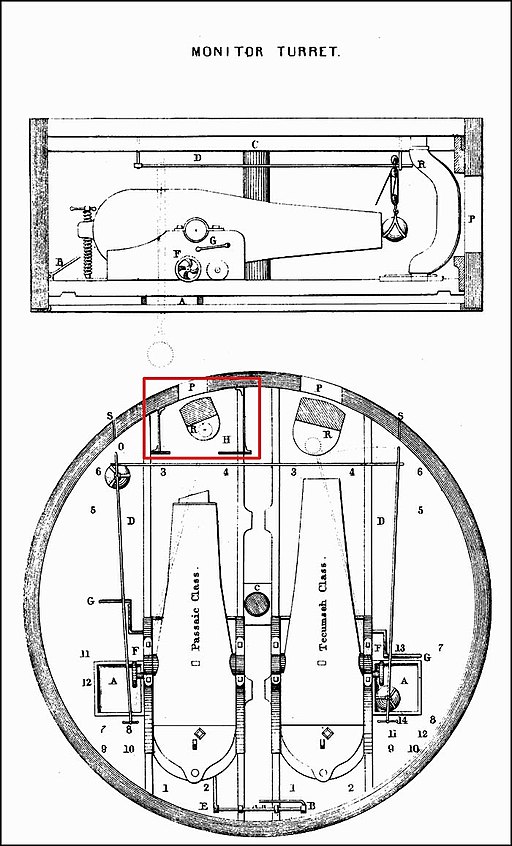

The original concept conceived that Roanoke would mount four Passaic-class style turrets. The great weight of these turrets with their guns was too great of a load for Roanoke’s frame. Instead, three Passaic-class turrets were used. These turrets were protected by 11 layers of one-inch iron plates. The forward two turrets mounted stationary pilothouses which were protected by nine layers of one-inch iron plates. Original plans were altered to enable Novelty Iron Works to armor the warship. The original plans called for six layers of one-inch iron plates; instead, Novelty installed a single 4.5-inch plate which was tapered to 3.5-inch below the waterline. The deck armor was designed to be 2.5 inches; however, it was cut down to 1.5 inch plate to save weight.[18]

Ironclad Design Errors

The Roanoke had numerous serious flaws. Each turret weighed 127 tons. Added to the turret weight were the heavy guns. A XV-inch Dahlgren: 43,000 lbs.; XI-inch Dahlgren: 16,000 lbs.; and 150-pounder Parrott rifle: 16,300 lbs.[19] This entire load was only supported by a series of stanchions that transferred the load to the ironclad’s bottom. Nothing was done to reinforce and strengthen the lower portion of the hull. The stress caused the ironclad to constantly leak. The ship had a very deep draft and only a six-foot freeboard which caused the ship to roll excessively, especially in heavy seas. The wooden hull was just not strong enough to manage the upperworks’ weight. The excessive draft meant that Roanoke could not operate in the shallow southern waters on blockade duty. And the freeboard was too small for Roanoke to operate as an ocean-going ironclad.[20]

Armament

The Roanoke’s battery was superior to most other ships afloat. While mounting only six guns; these weapons were some of the best and most powerful naval ordnance in existence. The Roanoke was designed to house four XV-inch shell guns; however, there was a limited number of these cannons available, so the builders substituted more XI-inch Dahlgrens. The forward turret contained one XV-inch shell gun and one 150-pounder Parrott rifle. The middle turret had one XV-inch and one XI-inch Dahlgren. The back aft turret had one XI-inch shell gun and one 150-pounder Parrott rifle]. Along with these heavy guns, Roanoke was also fitted with an ax-shaped ram which was formed from two 4.5-inch plates which reached two feet beyond the bow.[21]

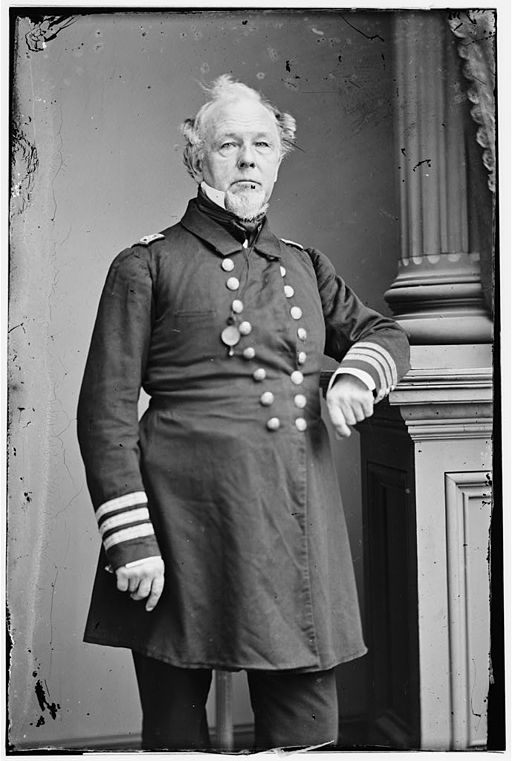

Iron, Somewhat Afloat

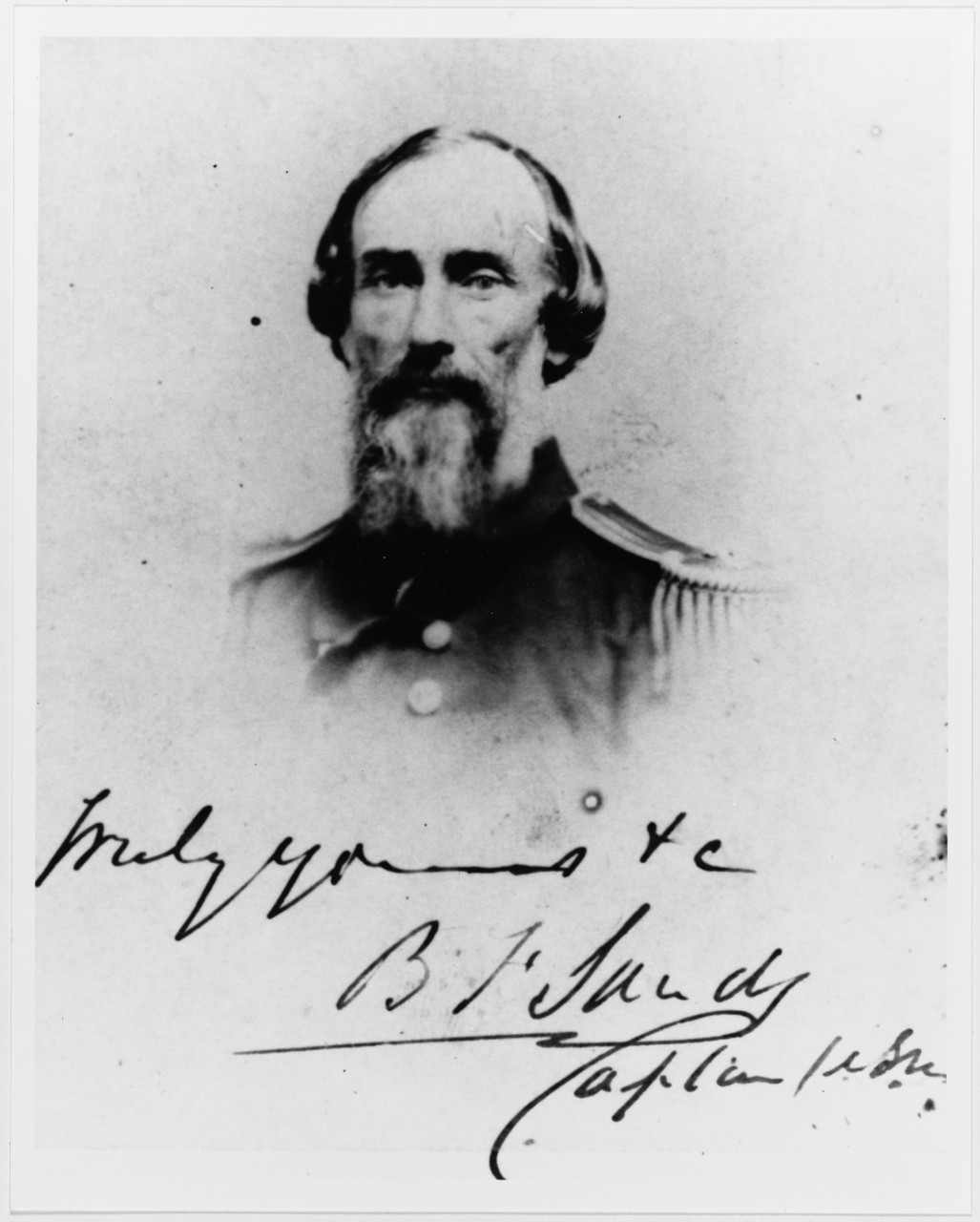

The Roanoke was recommissioned on June 29, 1863, Captain Benjamin F. Sands commanding. Sands was from a prominent military family and joined the US Navy as a midshipman on April 1, 1828. He served on the brig USS Washington during the Mexican War and was commander of the gunboat USS Dacotah prior to being detailed to command Roanoke.[22] He took the ironclad from New York in early July 1863 to Hampton Roads, Virginia. Even though the ship could make 8.5 knots and could cruise at 7 knots, that was the best news to come from that trip. The ironclad’s commander made a far more brutal assessment of the vessel.

Sands recorded that the heavy warship’s roll was so great that it would not enable “the possibility of fighting her guns and I was obligated to secure them with pieces of timber to prevent them fetching away.” Once in Hampton Roads, Sands test-fired the ship’s artillery. Both XV-inch Dahlgrens and one 150-pounder Parrott rifle had such a violent recoil that they were knocked off their carriages. Sands recommended that Roanoke remain in Hampton Roads as a harbor defense ship.[23]

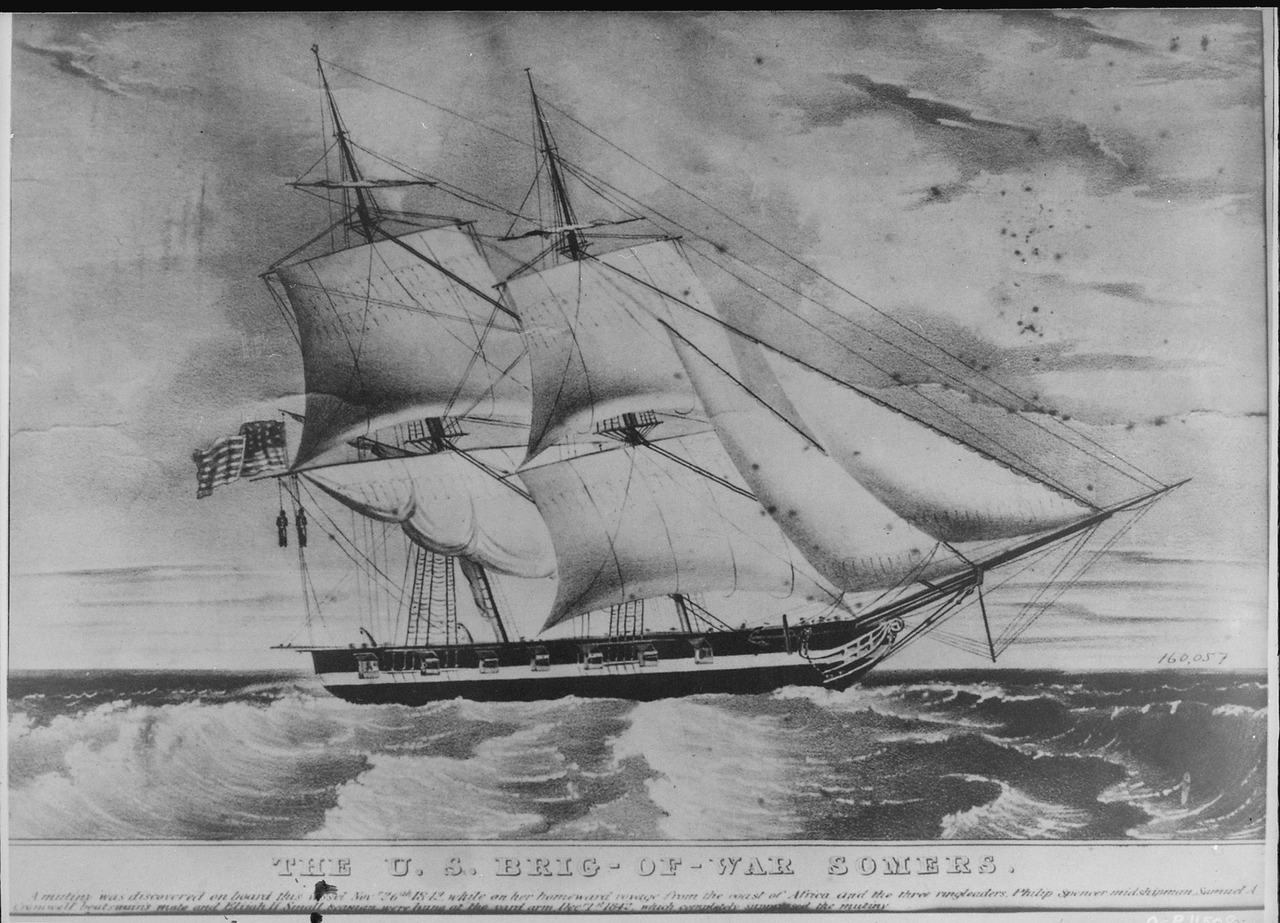

Captain Guert Gansevoort soon replaced Sands. Gansevoort was from a noted Dutch-American aristocratic family and his father was a US Army brigadier general. Guert Gansevoort was appointed midshipman on March 4, 1823. Promoted lieutenant in 1839, he was serving as first lieutenant aboard the brig USS Somers.

http://www.history.navy.mil/bios/mackenzie_a.htm

Perhaps one of most notable events of his career was the 1844 Somers Mutiny. The Somers was captained by Commander Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, a noted author, brother to Senator John Slidell, and brother-in-law to Oliver Hazard Perry. Midshipman Philip Spencer, son of the Secretary of War John C. Spencer, planned a mutiny to take over Somers. Spencer was arrested with many of his followers and, on the advice of Lt. Gansevoort, Spencer and two fellow co-conspirators were hanged from the yardarm of Somers. [24]

This event did not have a negative impact on Gansevoort’s career; however, his first cousin, Herman Melville, wrote his book, Billy Budd, based on Gansevoort’s experience on Somers. Gansevoort was promoted commander in 1845. He served with distinction during the Mexican War and in the 1856 Puget Sound War. Prior to his assignment as commander of Roanoke, Gansevoort was chief of ordnance, Brooklyn Navy Yard.[25]

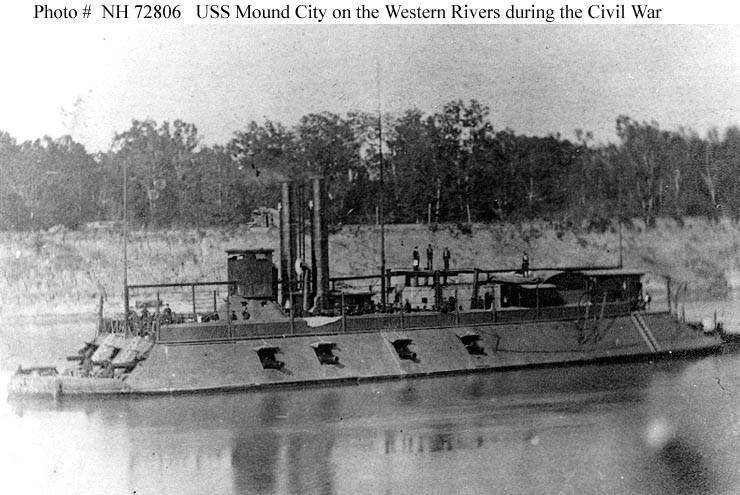

The final captain of the ironclad Roanoke was Captain Augustus Henry Kilty. Appointed midshipman in 1821 and promoted to lieutenant in 1837, Kilty was promoted commander in 1855 and was immediately placed on the Reserve List. Returning to the Active List in 1859, Kilty commanded the ironclad USS Mound City and fought at Island No. 10 and Fort Pillow on the Mississippi. Promoted captain on July 16, 1862, he was severely wounded during an expedition up the White River in Arkansas and lost his left arm. He commanded Roanoke during the last year of the war and took the ironclad to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for decommissioning, arriving on April 27, 1865.[26]

The ironclad was then placed in ordinary. The Roanoke’s only post war service was its use as a ceremonial flagship by Port Admiral of New York, Vice Admiral Stephen Rowan. The warship was briefly re-commissioned to host a delegation from the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs on August 11, 1874. Returning to Reserve, Roanoke was surveyed in 1876. This review indicated that “this ship requires rebuilding with an iron frame and plating.” The vessel was sold for scrap on September 27, 1883. [27]

Ironclad of the Future

The Roanoke was the first warship to mount three turrets on centerline. Called a “monitor” due to its use of turrets, the vessel was really a hybrid warship. The turrets gave Roanoke a wide arc of fire which limited the number of guns required for a broadside. Even though the ship’s guns were muzzleloaders, they were the best armament a vessel of the 1860s could mount. The 150-pounder Parrotts gave great range and accuracy to the ship’s battery, and the XV-inch Dahlgrens could destroy any Confederate ironclad afloat. The ship’s freeboard differed from all other monitors; however, it was still inadequate.

The Roanoke was an attempt to have an ocean-going ironclad; yet the re-use of the poorly supported wooden frame was simply unable to properly carry the weight of the armor, turrets, and guns. If Roanoke had been totally built of iron with a well-supported frame, the ironclad would have been a match for many of the experimental ironclads built during the 1870s to 1880s. Instead, the vessel was an expensive failure, destined to the scrap yard not long after the end of the Civil War.

NOTES

- Donald L. Canney, The Old Steam Navy: Frigates, Sloops and Gunboats, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press,1990, 174.

- Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies: 1855-1883, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2001, 17.

- Edwin Olmstead; Wayne E. Stark; Spencer C. Tucker. The Big Guns: Civil War Siege, Seacoast and Naval Cannon. Alexandria Bay, New York: Museum Restoration Service, 1997, pp.87-88.

- Oliver W. Griffiths, “The New War Steamers,” United States Nautical Magazine (April 1855): p.302.

- Ibid.

- Spencer C. Tucker, ed., The Encyclopedia of the Mexican War: A Political, Social and Military History, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2013, p.280.

- William O. Scoggs. Filibusters and Finances: The Story of William Walker and His Associates, New York: The Macmillan Co., 1916, pp. 333-336.

- Canney, The Old Steam Navy: Frigates, Sloops and Gunboats, pp. 59-60.

- Silverstone, p. 17.

- Department of the Navy, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of Rebellion, 30 vols., Washington: Government Printing Office, (Hereafter referred to as ORN), 1, 6:336.

- Joseph McDonald, “How I Saw the Monitor-Merrimac Fight,” New England Magazine (July 1907): 548.

- ORN,1,6:363.

- Ibid.

- Henry Ashton Ramsay, ‘Wonderful Career of the Merrimac,” Confederate Veteran (July 1907): 310.

- Samuel Dana Greene, “I Fired the First Gun,” American Heritage (June 1957): 103.

- Canney, Donald L. The Old Steam Navy: Ironclads, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1993: p.59-60.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Olstead, pp.87-88.

- Silverstone, 4.

- Ibid.

- Benjamin F. Sands, Rear Admiral, US Navy. Arlington National Cemetery online. www.arlingtoncemetery.net/b.f.sands.htm; Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy & Marine Corps Officers 1775-1900, www.ibiblio/hyperwar/NCH/Callahan/re-usn-s.htm. Accessed September 13, 2020.

- Canney, The Old Steam Navy, 60.

- Commander Alexander Slidell Mackenzie. Naval History and Heritage Command online. https://history.navy.mil./research/histories/bios/mackenzie-alexander.html Accessed September 13, 2020.

- Rear Admiral Guert Gansevoort. Naval History and Heritage Command online. https://history.navy.mil./research/histories/bios/gansevoort-guert.html Accessed September 13, 2020.

- “The records of officers of the US Navy and Marine corps: with a history of naval operations during the rebellion of 1861-1865, and a list of the ships and officers participating in the great battles.” archive.org/stream/cu31924098819968/cu_djvatext. Accessed September 13, 2020.

- Canney, The Old Steam Navy: Ironclads, 62.

REFERENCES

Canney, Donald L. The Old Steam Navy: Ironclads. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1993.

—-. The Old Steam Navy: Frigates, Sloops and Gunboats. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1990.

Department of the Navy. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of Rebellion, 30 Volumes. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904.

Greene, Samuel Dana. “I Fired the First Gun.” American Heritage. June 1957.

Griffiths, Oliver W. “The New War Steamers.” United States Nautical Magazine. April 1855.

Olmstead, Edwin; Wayne E. Stark; and Tucker C. Spencer. The Big Guns: Civil War Siege, Seacoast and Naval Cannon. Alexandria Bay, New York: Museum Restoration Service, 1997.

MacDonald, Joseph. “How I Saw the Monitor-Merrimac Fight.” New England Magazine. July 1907.

Ramsay, Henry Ashton. “Wonderful Career of the Merrimac.” Confederate Veteran. July 1907.

Scroggs, William O. Filibusters and Finance: The Story of William Walker and His Associates. New York: The Macmillan Co. 1916.

Silverstone, Paul. H. Civil War Navies:1855-1883. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. 2001.

Tucker, Spencer C., ed. The Encyclopedia of the Mexican War: Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABS-CLIO. 2013.

—. Handbook of 19th Century Naval Warfare. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. 2000.