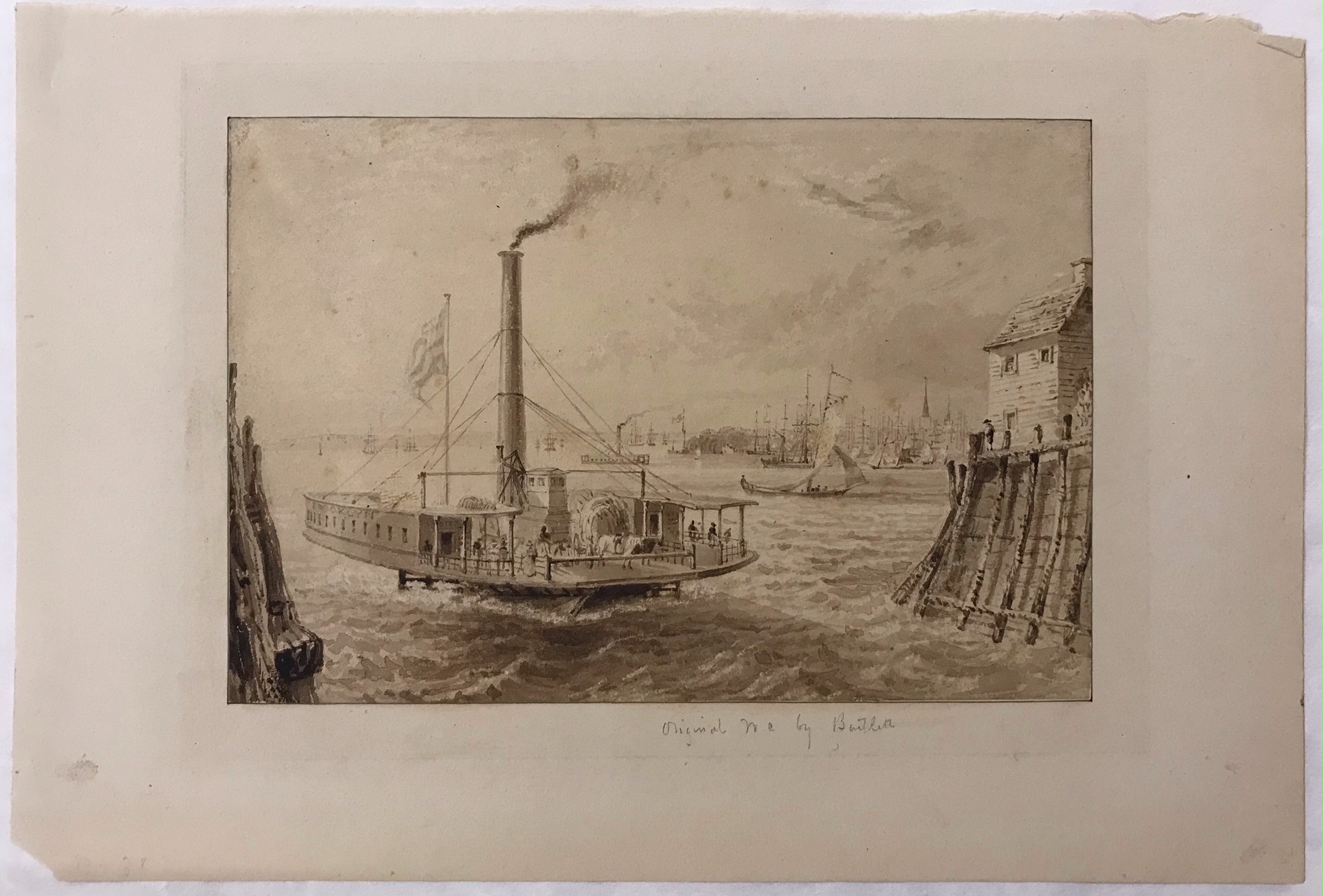

I have recently spent a lot of time with an artist named William Henry Bartlett (1809-1854*). Not really him, more like the printed engravings made from his artwork, but we have over 100 in the collection so I kind of feel like he is family now. After cataloging so many of his prints I started to notice that I was typing the same thing over and over: steamship in the background, steam coming from the funnels. The more I looked the more I saw them, sometimes featured in the image but often in the far distant background. That made me wonder, what was it about these steamships that fascinated Bartlett so much that he included them in his artwork on a regular basis?

*As an aside, there is a second British artist named William Henry Bartlett who lived from 1858-1932.

The answer could be as simple as saying that the steamships were just there in the scene, the same way the water, mountains, and bridges were waiting for Bartlett to paint. Except that I like to think that it’s a little more romantic than that. William Henry Bartlett was a prolific artist who traveled the world to produce images for illustrated travel books from the late 1830s through the early 1850s. Kind of sounds like an artist’s dream job, right: get paid to travel, create art, and surround yourself in gorgeous scenery.

Bartlett started his career as an apprentice studying under John Britton in 1822 when he was only 13 years old. Many of his first drawings focused on the architecture of the buildings and ruins that he and Britton visited, giving his work a detailed, structural quality that he blended well with his love of landscapes. The apprenticeship ended in 1829 but Bartlett stayed on with Britton until he began working for George Virtue, a publisher with offices at 26 Ivy Lane in London. Virtue and later his son, James S. Virtue, published many books with Bartlett’s artwork.

The timing of when Bartlett worked is significant in the history of steam navigation. Steam engines came about in the 1700s, eventually making their way onto boats and providing a source of power that was not dependent on the whims of the winds or the water currents. There is a list of experiments and inventors in steam engines and steamboats that spans several decades and countries, including Denis Papin and Claude de Jouffroy of France, and John Allan, Johnathan Hulls, and James Watt of England. In the United States John Fitch first successfully built and operated a steamboat in 1787, but it was not a commercial success due to the expense of construction and operation.

Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston are the first Americans to successfully build and operate a steamboat, and also make money from the effort. Fulton’s ship, North River Steamboat or as the public came to know it the Clermont, first traveled the 40 miles from New York to Albany on August 17, 1807 and set a record of eight hours for the trip. By the 1830s and 1840s when Bartlett was drawing landscapes around the world steamboats were a common way to travel and ship goods.

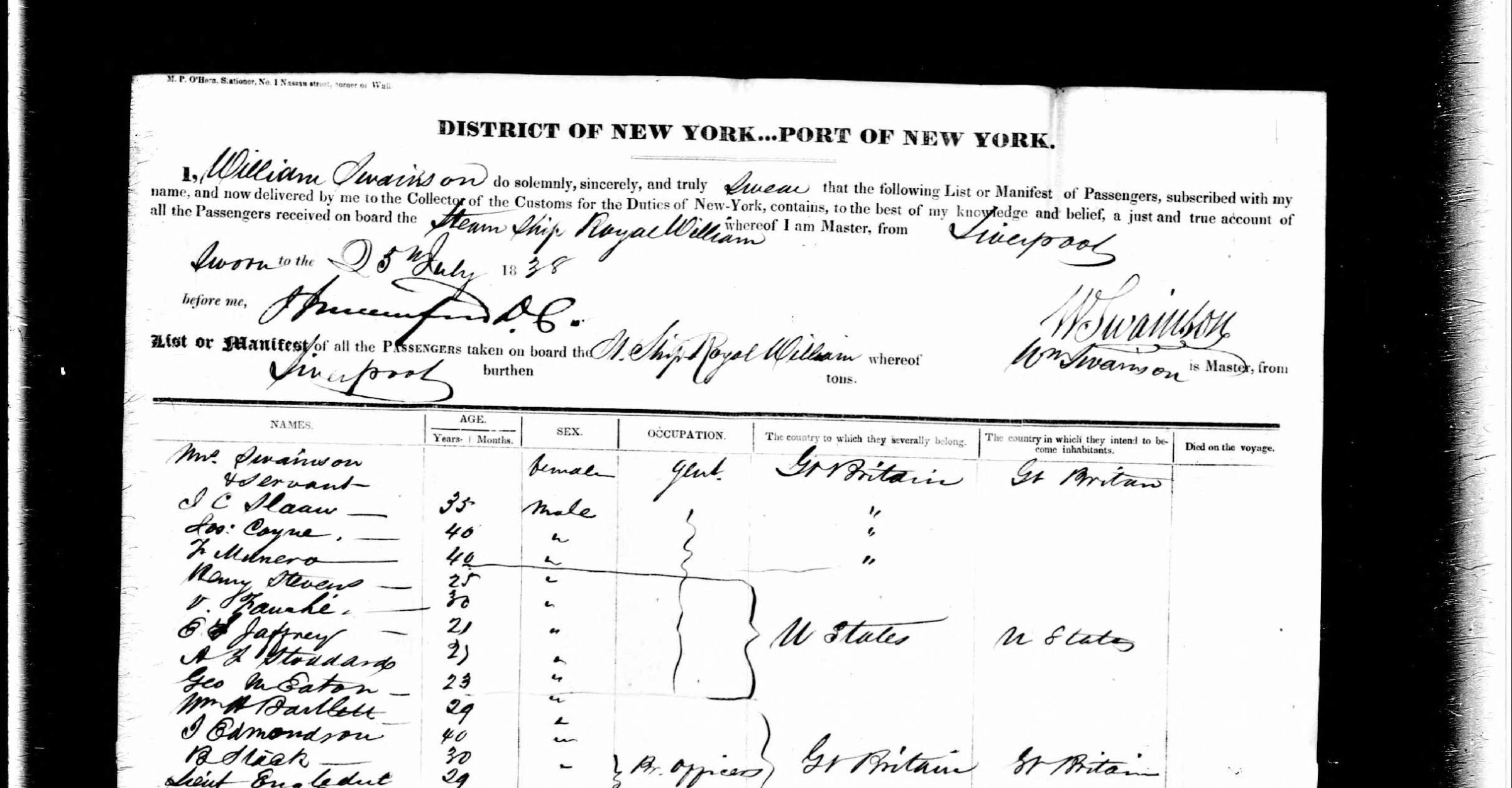

Bartlett had many interactions with steamboats during his lifetime. His travels included the Mediterranean, the Bosporus, much of Europe, as well as Canada and the United States. Bartlett came to the US in 1836 on the packet ship Silvie de Grasse (sometimes spelled Sylvia de Grasse), and then visited again in 1838 on the steamship Royal William.

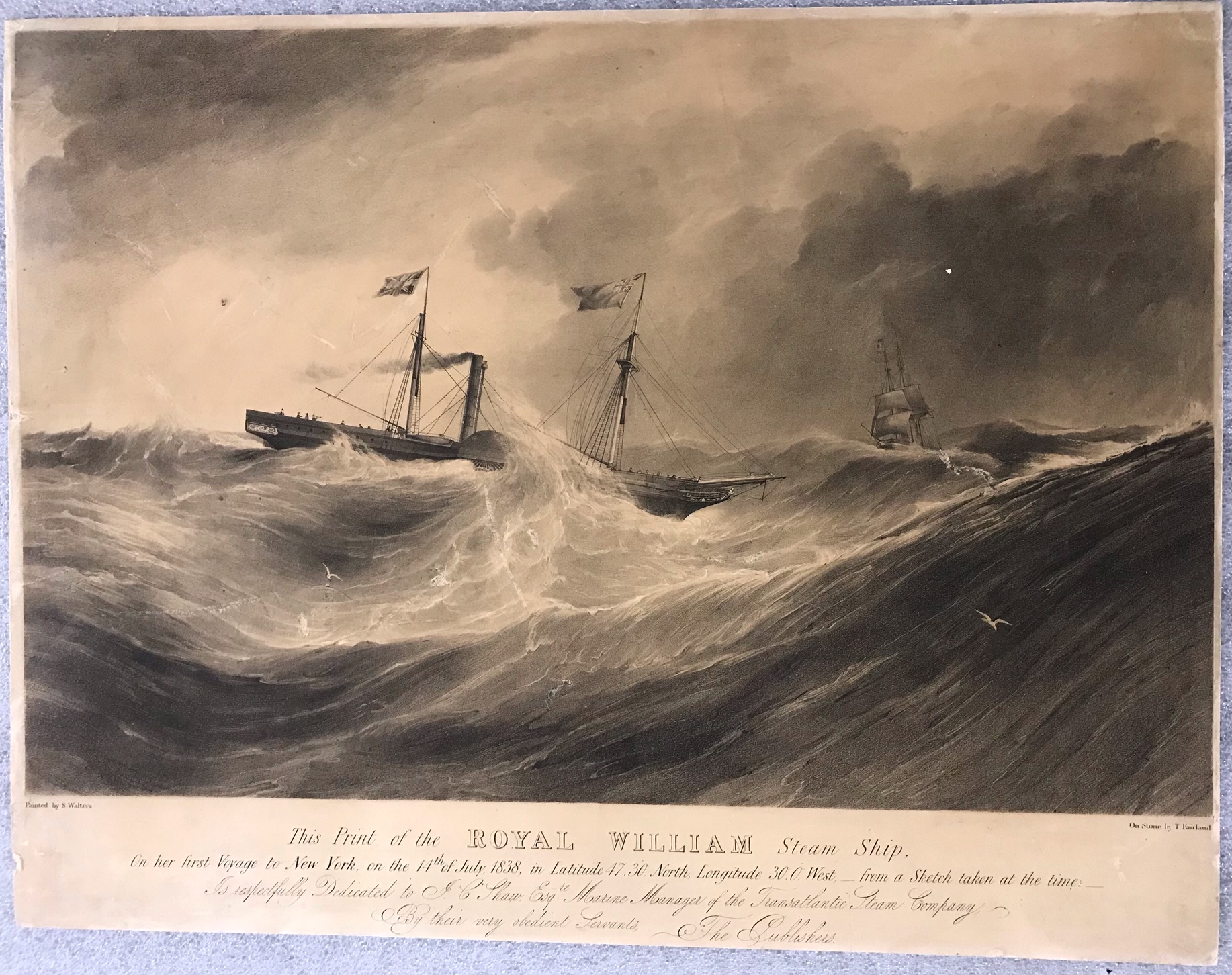

The trip on the Royal William was unique for several reasons. First, it made the trip through some very bad weather, so much that on July 13, 1838 Captain Swainson noted in his log, “During these 24 hours we had extraordinary weather…A winter passage cannot be worse than ours up to this period. Several of our passengers, who have crossed the Atlantic often in their lives, say they never experienced worse weather or heavier seas.” Yikes!

The second reason this trip was special is because it was the ship’s first trip across the Atlantic, from Liverpool to New York with no port calls. The news of the arrival made the newspapers in Europe and the United States, and our good friend Bartlett was there for the adventure.

This was the second of his four trips to North America but I am sure that it made an impression on him. As much as he travelled, he is sure to have been on many other steamships, until he died while onboard the French steamer Egyptus in September 1854. He had been sailing toward home from Malta to Marseilles and the crew buried him at sea.

The prints that Bartlett produced show the cities and landscapes of many different parts of the world at a major turning point in the history of transportation and technology. The development and application of the steam engine gave sailors and passengers the freedom to travel in almost any direction regardless of what the winds and currents had in mind, which allowed the ship owners to increase the speed of their ships and thereby increase their profits. The world grew just a little smaller as the various countries were able to reach more distant lands in less time, and Bartlett was along for the ride.