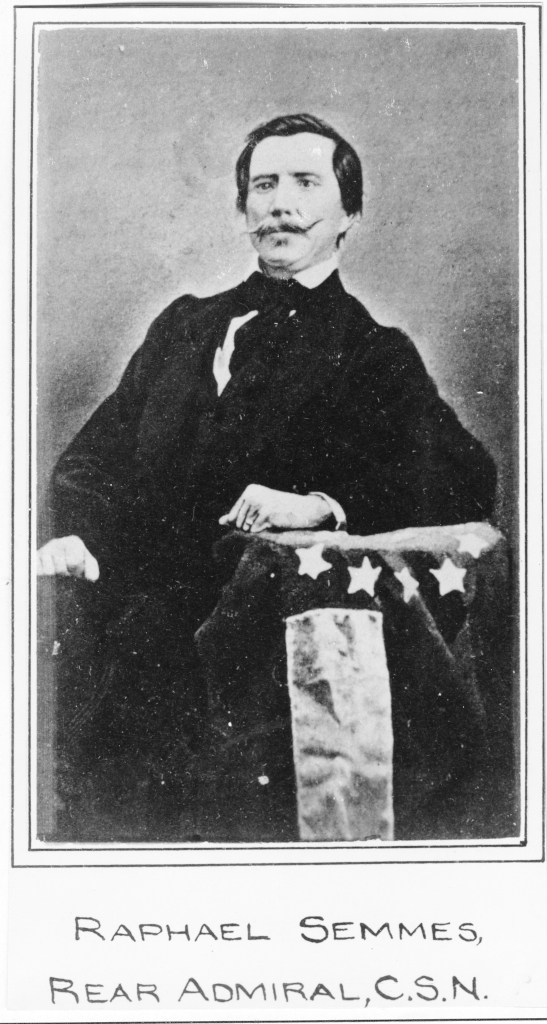

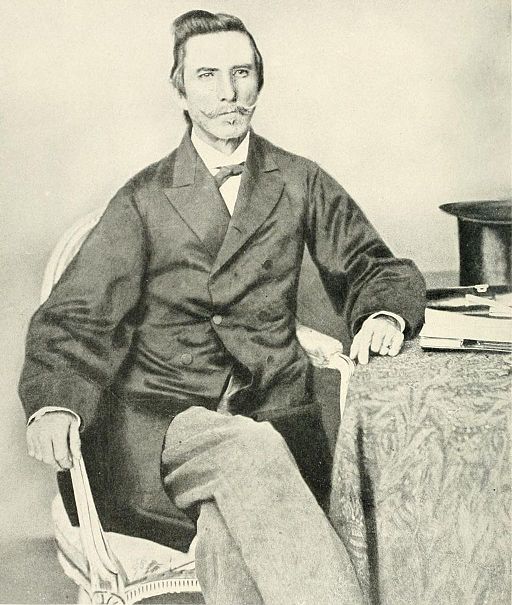

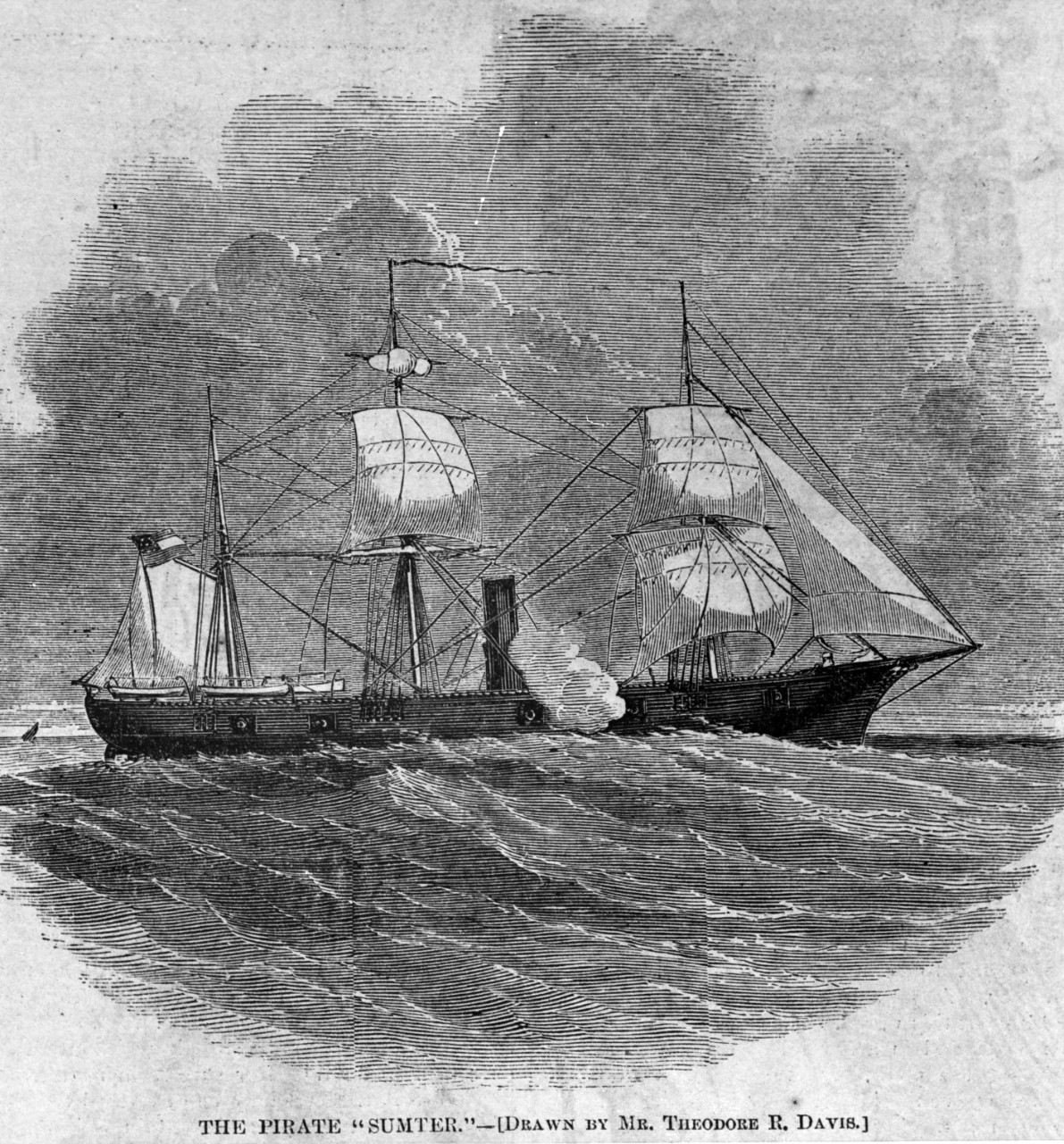

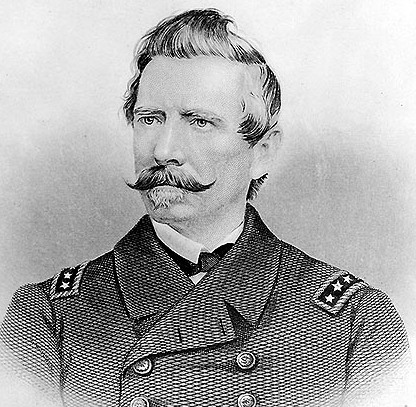

The CSS Sumter was fitted out as a cruiser by the CS Navy at New Orleans, Louisiana. Commander Raphael Semmes, a former US naval officer who had served with distinction during the Mexican War, had resigned his commission and joined the Confederate navy. Immediately, he sought an active command. He met with Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory seeking the command of a cruiser that could harass Union shipping. Consequently, Mallory gave Semmes command of a ship in the making, CSS Sumter. The Sumter’s cruise launched the career of one of the greatest commerce raider commanders in history.

EARLY DAYS

Raphael Semmes was born in Charles County, Maryland, on September 27, 1809. Orphaned at an early age, he was raised by his uncle, Raphael Semmes. The young Raphael was a cousin of Brigadier General Paul Semmes and Union Captain Alexander Alderman Semmes. He attended Charlotte Hall Military Academy and at age 17, thanks to the influence of another uncle, Benedict Semmes, he was appointed to the US Navy as a midshipman. He took a leave of absence to study law and was later admitted to the Maryland Bar in 1834. Continuing on shore duty he was able to expand his law practice. Semmes was promoted lieutenant in February 1837. During the same year he married Anne Elizabeth Spencer of Ohio. The happy union produced six children. [1]

ON THE ROAD TO MEXICO CITY

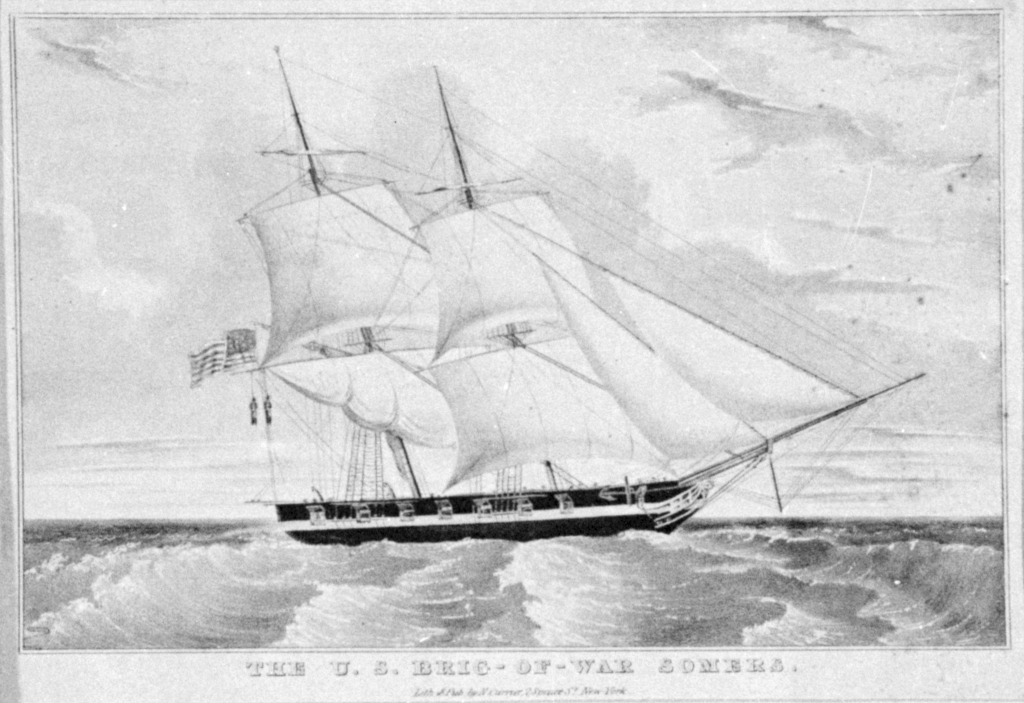

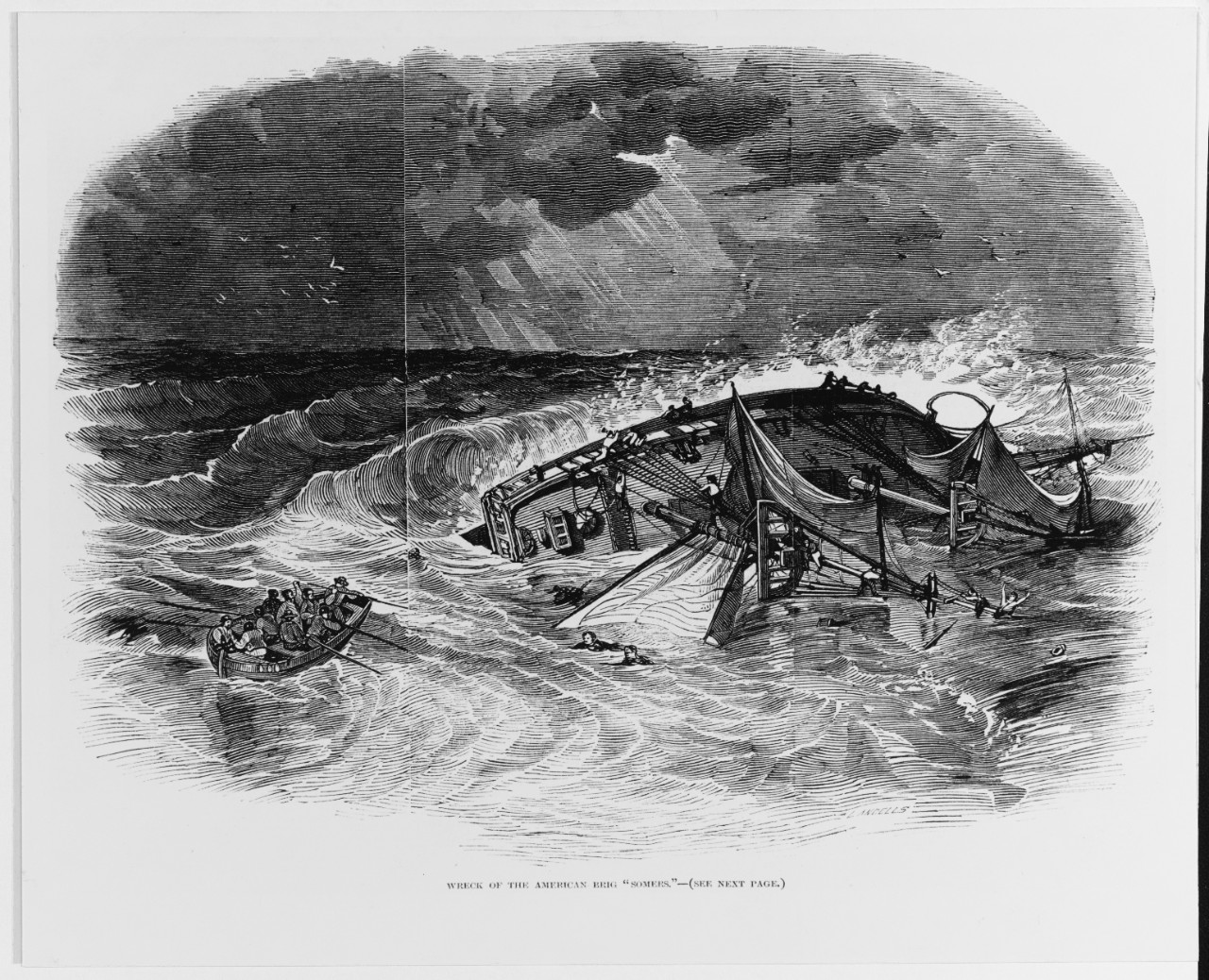

In 1845, Lieutenant Semmes was named commander of the infamous brig USS Somers. The Somers was noted for the hanging of three mutineers on December 1, 1842, including Philip Spencer, son of the Secretary of War John Spencer. Despite being labeled a “cursed ship,” Semmes captained the brig in the Gulf of Mexico off Vera Cruz when the Mexican War erupted. The Somers took Commander Duncan N. Ingraham to Campeche to discuss the efforts of citizens of the Yucatan Peninsula to secede from Mexico.[2] Once this was confirmed, Semmes took Ingraham back to Vera Cruz and continued to blockade the Mexican Gulf coast.

On December 8, 1846, while chasing a blockade runner, Somers ran into a sudden squall. Despite Semmes’s efforts to save his ship, it floundered. Semmes barely escaped drowning and 44 of his crew of 80 were rescued by British, French, and Spanish ships. In the aftermath, Semmes was praised by a court of inquiry for the manner in which he handled his ship in such difficult circumstances.[3]

Semmes was reassigned to the 44-gun frigate Raritan, commanded by Captain French Forrest. Forrest organized the landing of United States troops to begin the siege of Vera Cruz.

The landing site, Collado Beach, had a small anchorage so it was decided that transports would take soldiers ashore. Once these vessels had delivered the men, other vessels would then bring in supplies. This long and arduous process was guided by Forrest with the assistance of Lt. Semmes. Semmes continued with Lieutenant General Winfield Scott’s army on the road to Mexico City. Semmes was detailed to deliver to Mexican authorities a request for the release of POW Passed Midshipman R. Clay Rogers. This vexed Gen. Scott as he did not like to waste escorts on useless messages. [4] Nevertheless, Semmes continued with the army as it reached Mexico City.

The naval lieutenant was there during the September 13, 1847, assault on San Cosme Garita. The American troops, led by Brigadier General William Worth, had to cross a long causeway defended by several Mexican cannons. The stalemate was broken when Lieutenant U. S. Grant and elements of the 6th Infantry took a mountain howitzer up into the tower of San Cosme church. Lt. Semmes did likewise on the other side of the causeway. The combined actions of Grant and Semmes enabled Worth’s command to break through the Mexican defenses. Scott’s army then occupied Mexico City and the war was basically over. [5]

ANTEBELLUM DAYS

Once the Mexican War ended, Semmes moved to Mobile, Alabama. While on shore duty there, he practiced law and published a book in 1851 about his experiences in the Mexican War, Service Afloat and Ashore During the Mexican War. Semmes was promoted commander in 1855, and the next year, he was named inspector for the Lighthouse Service in Washington, D.C. This newly formed agency was given the duty to oversee and regulate all operations related to navigational aids including lighted buoys, light ships, and lighthouses. Highly educated and intelligent individuals, like Semmes, were assigned to this service which maintained 12 different lighthouse districts. [6]

CIVIL WAR ERUPTS

When Alabama left the Union after Abraham Lincoln’s election as president of the United States, Raphael Semmes resigned his commission and headed to Montgomery, Alabama, then capital of the Confederacy, on February 18, 1861. Semmes reflected on his new career as “a new book, whose pages were yet all blank, has been opened.”[7] Several other officers from the old Navy had already resigned their commissions. Of these, only Victor Randolph, Lawrence Rousseau, Duncan Ingraham, and Semmes were in Montgomery to meet with the Confederate Congressional Committee on Naval Affairs to discuss what the Confederacy could do to defend its ports and the Mississippi River.

With no ships, the committee had a difficult task before them. Semmes met with the newly elected President Jefferson Davis on February 19, 1861. Davis sent Semmes on a mission to the North to obtain arms and ammunition. [8] A few days later, the Confederate Department of the Navy was formed with Stephen Russell Mallory as its secretary. Mallory contacted Semmes while he was in the North and asked him to purchase one or two steamers capable of mounting XIII- or IX-inch shell guns. The mission proved to be fruitless.

Upon his return from this failed effort, Commander Semmes was nominated to be head of the Lighthouse Board. This was the last position that Semmes wanted as he desperately wished for a command at sea. So, he went to Mallory and shared his concept of launching a war at sea against Northern merchant ships. Semmes knew that the best way to weaken the Union was to attack its commercial wealth. Mallory agreed. [9]

The secretary knew that Raphael Semmes was a seasoned seaman. Semmes exhibited valued leadership skills such as being resolute, capable, and brave These qualities made Semmes the perfect officer to begin the Confederate commerce raiding campaign. To Semmes, it was a unique opportunity to fly, for the first time, the Confederate flag at sea.

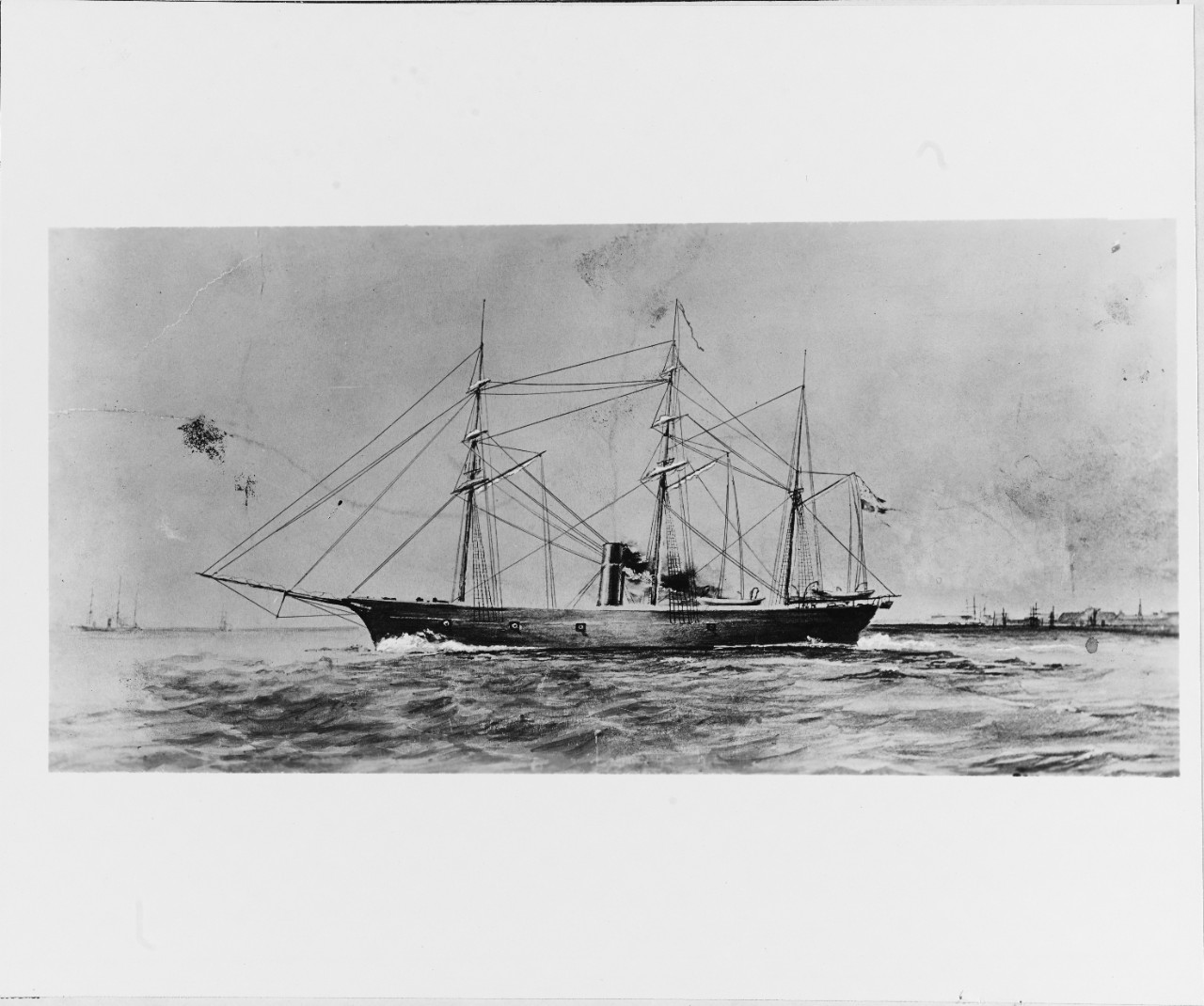

Meanwhile, in New Orleans, Captain Rousseau had identified two ships, Habana and Marques de la Havana, that could be converted into warships. Immediately after reading Rousseau’s report, Semmes told Mallory that Habana would be perfect for commerce raiding. Accordingly, Mallory authorized the ship’s purchase. Semmes was detailed to assume command of the newly minted CSS Sumter and worked hard to transform the merchant ship into a fighting cruiser. [10]

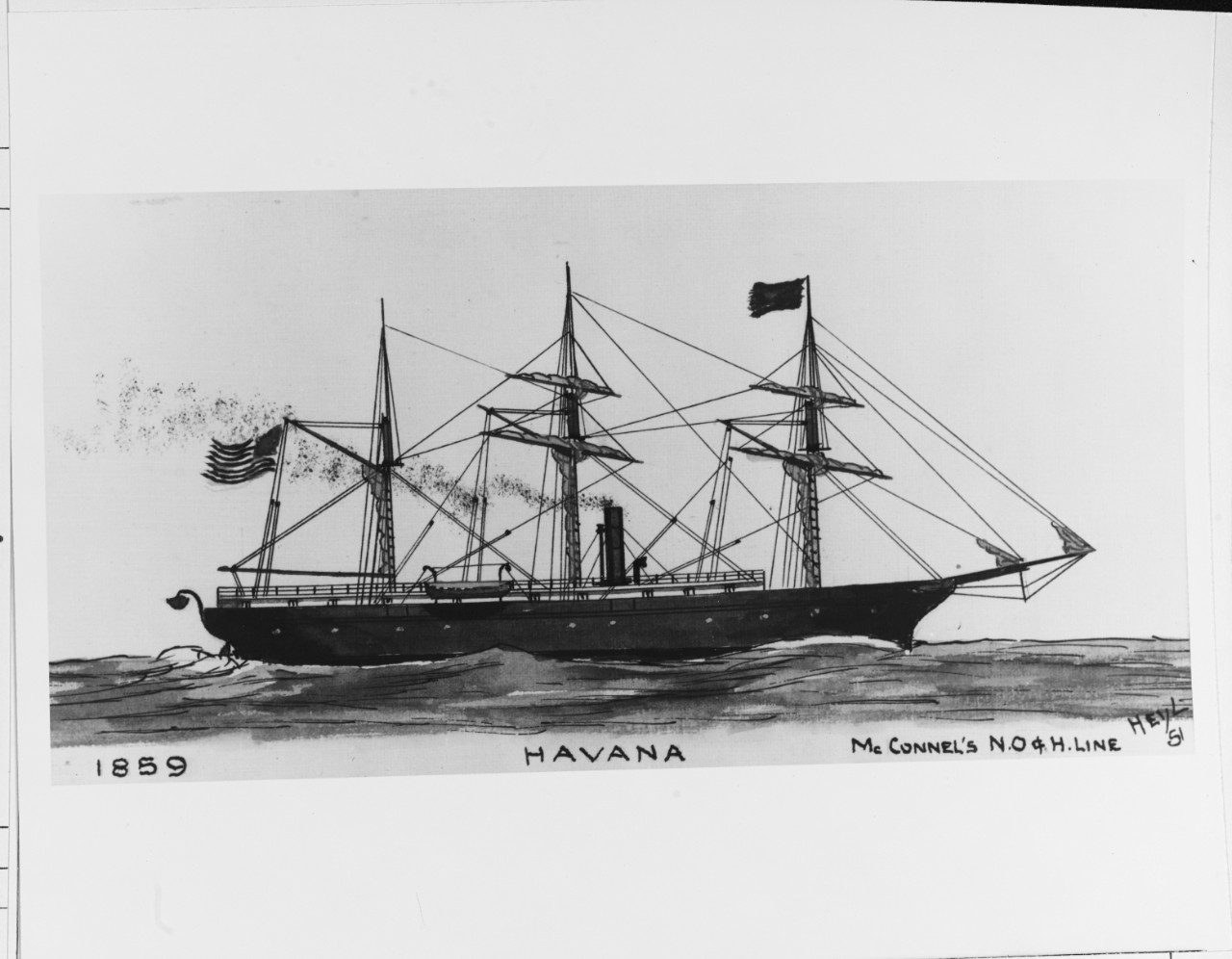

THE HABANA

The Habana was originally built in 1859 at the Birely & Lynn Shipyard in Philadelphia for Captain James McConnell’s New Orleans & Havana Steam Navigation Co. The vessel was considered extremely fast and was employed in a mail carrying service. The engine system was fabricated by the Philadelphia firm of Neafie, Levy & Co. The engine produced 400 horsepower to turn a single screw propeller. The ship could cruise at 10 knots and the steamer’s only weakness appeared to be limited space to bunker coal. Consequently, Habana was bark-rigged; and had a length of 184 ft., a beam of 30 ft., and a draft of 12 ft. [11]

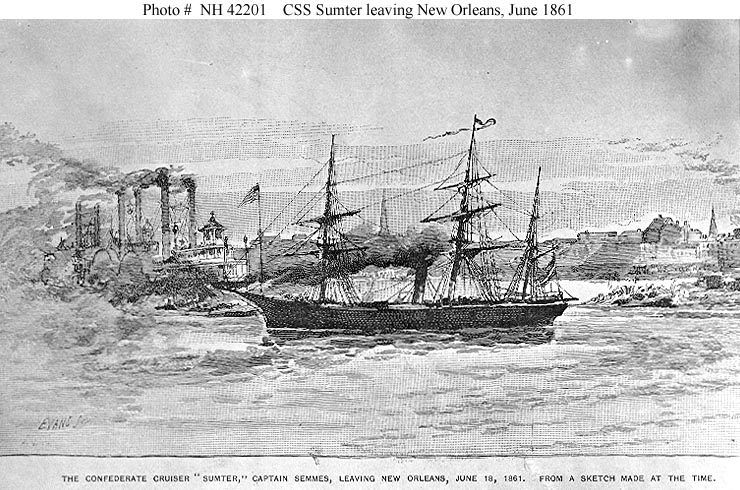

Line engraving. Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 42201

TRANSFORMATION

When Semmes arrived in New Orleans he surveyed Habana, now with a new name, CSS Sumter. He found the vessel to be “a good steamship” and he thought, “Her lines were easy and graceful, and she had a sort of saucy air about her.” [12]

The effort to transform the steamer into an effective raider consumed all of Semmes’s energies. The work was completed by a shipyard in Algiers, across the Mississippi from New Orleans, as Sumter rapidly changed its appearance. The staterooms were all removed to make room for the ship’s artillery. Within the ship, other improvements included: strengthening the deck to handle the weight of the guns and building beneath it a mess deck, coal bunkers, powder magazines, water tanks, and other necessary modifications. Semmes had to do it all as no shipyard in New Orleans had ever built a warship. Accordingly, the Confederate commander had to make all the designs himself and instruct the workers how to implement them. [13]

The next major problem that Semmes had to resolve was Sumter’s battery. Semmes endeavored to have a local company, Phoenix Foundry, to make 24-pounder howitzers; however, this firm was unable to produce a satisfactory product. Although Mallory suggested that Semmes use old cannons from Fort Jackson or Fort St. Philip, the clever Semmes learned of the recent capture of Gosport Navy Yard. He asked the secretary of the navy for artillery that could be found there. He requested one XIII-inch Dahlgren for use as a pivot gun and four 32-pounders.

Not only did Semmes have to track the shipment of these guns from Portsmouth, Virginia, to New Orleans, he also had great difficulty in securing adequate gunpowder and proper carriages for his cannon as well as obtaining small arms. Somehow, Sumter’s captain was able to achieve all of these things. On June 3, 1861, Semmes, with 107 officers and crew, was able to test his guns and engines to prepare to run the blockade. [14]

AT SEA AT LAST

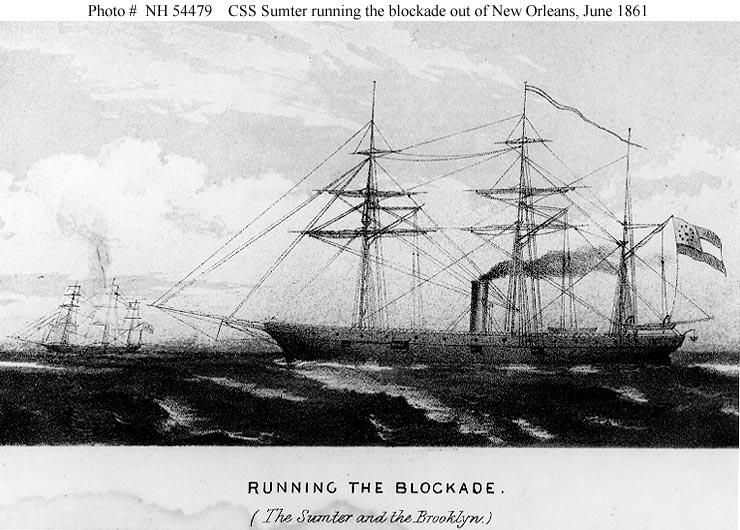

While Semmes prepared his vessels, more Union ships arrived to enforce the blockade of the Mississippi. Rather powerful ships were stationed where each pass entered the Gulf of Mexico. The most dangerous was the steam screw sloop of war USS Brooklyn. Commissioned in 1859, Brooklyn could make almost 12 knots. The sloop was armed with one X-inch shell gun mounted in pivot along with 20 IX-inch Dahlgrens in broadside. The Brooklyn’s 30-year naval veteran captain, Commander Charles Henry Poor, knew all about Sumter’s planned escape and was determined to destroy the Confederate cruiser. With greater speed and firepower, the extremely aggressive Commander Poor realized that, if given the chance, his ship could blow Sumter out of the water. [15] By a chance of fate, the daring Semmes planned to take his cruiser out of the Pass a l’Outre, right where Brooklyn was stationed.

By luck, on June 30, 1861, a fisherman came by Sumter with the news that Brooklyn had gone on a chase of an unknown ship. This was just the news Semmes needed to orchestrate his escape. The Sumter rushed out of the Pass a l’Outre; however, Poor noticed the Confederate cruiser and gave chase. The Brooklyn almost got into range of the raider; yet Semmes’s superior sailing skills enabled Sumter to reach the open sea at last. [16]

THE FIRST CONFEDERATE COMMERCE CRUISER

Semmes sailed his ship toward Cuba; and, near there, he captured his first prize on July 3, 1861, the Union merchantman, Golden Rocket. The ship was in ballast, so it was captured, the crew was removed, and it was set afire. Semmes remembered the scene of his first capture: “The burning ship, with the Sumter’s boat in the act of shoving off from her side, the Sumter herself, with her grim black sides, lying in repose like some great sea monster … and the sleeping sea … were all brilliantly lighted. The flames … could be heard roaring like the fires of a hundred furnaces, in full blast.” [17]

Over the next three days, while cruising the Caribbean Sea, Semmes burnt or bonded seven ships including: Cuba, Machias, Albert Ames, Ben Dunning, Lewis Kilham, Naiad, and West Wind. By the end of July 1861 two more Northern ships were captured. [18] By early August, news of Sumter’s depreciations against Northern commercial interests prompted business leaders to call for some action. Semmes and his crew were considered pirates and had to be stopped. The US Navy dispatched several ships to look for this “ghost ship.” The steam screw sloop of war USS Iroquois appeared to have trapped Sumter inside the port of St. Pierre, Martinique. Nevertheless, Semmes, with the help of the French authorities, managed to escape on the evening of November 23, 1861.

END OF THE CRUISE

Nonetheless, time was running out for Sumter. Several Union ships were searching the seas to capture or destroy, and the raider desperately needed fuel and machinery repair. Short on coal, Semmes put in at Cadiz, Spain. The Spanish government had been convinced by Union diplomats that Sumter was a pirate ship; so, Spain refused to allow the cruiser to resupply. Semmes then sailed to Gibraltar capturing two ships en route.

Once there he was unable to procure coal or arrange for repairs. Three Union warships — USS Kearsarge, USS Chippewa, and USS Tuscarora — appeared off Gibraltar blocking any escape. Consequently, Semmes paid off the crew and de-commissioned the Sumter. Semmes and his officers returned to London with plans to return to the Confederacy. Once they reached Nassau, Semmes received orders to return to Great Britain where he would assume command of a new commerce raider. [19] “Old Beeswax,” as his crew liked to call him because of his unusual moustache, would soon resume his attacks on Union commerce in a much more powerful fashion.

The Sumter proved that Confederate commerce raiding was rather effective in causing financial damage upon Northern business interests. Furthermore, this raider had somewhat weakened the Union blockade of the Southern coastline as the US Navy had to send some of its best ships to locate and destroy raiders like Sumter.

In just over six months, Sumter had destroyed or bonded 18 Northern merchant ships. Mallory knew, as did Semmes, that this type of assault on Northern businesses had to continue.

NOTES

1 Stephen Fox, Wolf of the Deep: Raphael Semmes and the Notorious Confederate Raider Alabama, New York: Vintage Books, 2007, p. 23.

2 K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848, New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1974, 109-110.

3 Raphael Semmes, Service Afloat and Ashore in the Mexican War, Cincinnati: Moore & Anderson, 1851, 94-95.

4 Ibid, 159-161.

5 Bauer, 314-316.

6 Sarah Kay Bierle, “The Lighthouse Board: 1852-1910,” gazette 665 online. gazette665.com/2017/07/26/the-lighthouse-board-1852-1910/, accessed October 5, 2020.

7 Raphael Semmes, Memoirs of Service Afloat, New York: J. P. Kennedy and Sons, 1869, 81.

8 Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Ser. 4, Vol. 1, p.106.

9 Semmes, Memoirs of Service Afloat, p. 92.

10 Ibid.

11 Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies, 1855-1883, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2001, p. 162.

12 Semmes, Memoirs, p. 96.

13 Raimondo Luraghi, A History of the Confederate Navy, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1996, 79-80.

14 Semmes, Memoirs, 99-109.

15 Silverstone, p. 21.

16 Semmes, Memoirs, 112-114; and Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Washington, DC: Government Printing House, 1894. Ser.1, Vol. I, p 34.

17 Semmes, Memoirs, p. 121.

18 Silverstone, p. 162.

19 Semmes, Memoirs, p. 329.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bauer, K. Jack, The Mexican War, 1846-1848. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. 1974.

Bierle, Sarah Kay. “The Lighthouse Board: 1852-1910.” Gazette 665 online. gazette665.com/2017/07/26/the-lighthouse-board-1852-1910/. Accessed October 5, 2020.

Fox, Stephen. Wolf of the Deep: Raphael Semmes and the Notorious Raider Alabama. New York: Vintage Books, 2007.

Luraghi, Raimondo. A History of the Confederate Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. 1996.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series 4, Volume 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1904.

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series 1, Volume 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894.

Semmes, Raphael. Service Afloat and Ashore in the Mexican War. Cincinnati: Moore & Anderson. 1851.

_____. Memoirs of Service Afloat. New York: J. P. Kennedy & Sons.1869.

Silverstone, Paul H. Civil War Navies, 1855-1883. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. 2001.