The Civil War introduced many new technologies to achieve victory in a total war. Although balloonists like John LaMountain and Thaddeus Lowe achieved considerable fame during the war, they were not the first military balloonists. The Chinese used paper balloon ‘lanterns’ sometime between 229 to 234 AD., when Chancellor Zhuge Lang’s army was surrounded by Mongolian troops. Lang employed hot air balloon lanterns to signal for reinforcements. It was the French who first employed a hot air balloon in combat. The Montgolfier brothers tested balloon flight between 1782 to 1784. Using a balloon made of silk or cotton stretched over a wooden frame, they proved the feasibility of flight.

During the French Revolution’s War of the First Coalition, the French employed their Aerostatic Corps using the balloon l’Entreprenant to observe the Austro-Dutch army during the June 26, 1794 Battle of Fleurus. Napoleon disbanded the Aerostatic Corps in 1799. When Venice attempted to free itself from the Austrian Empire, the Austrians used hot air balloon bombs during the siege of that city. About 200 balloons were launched from the deck of the SMS Vulkan. Only one hit a target as the wind shifted to send the bombs back over the Austrian lines. These ballooning activities set the stage for balloon advances during the American Civil War.

The First Aircraft Carrier

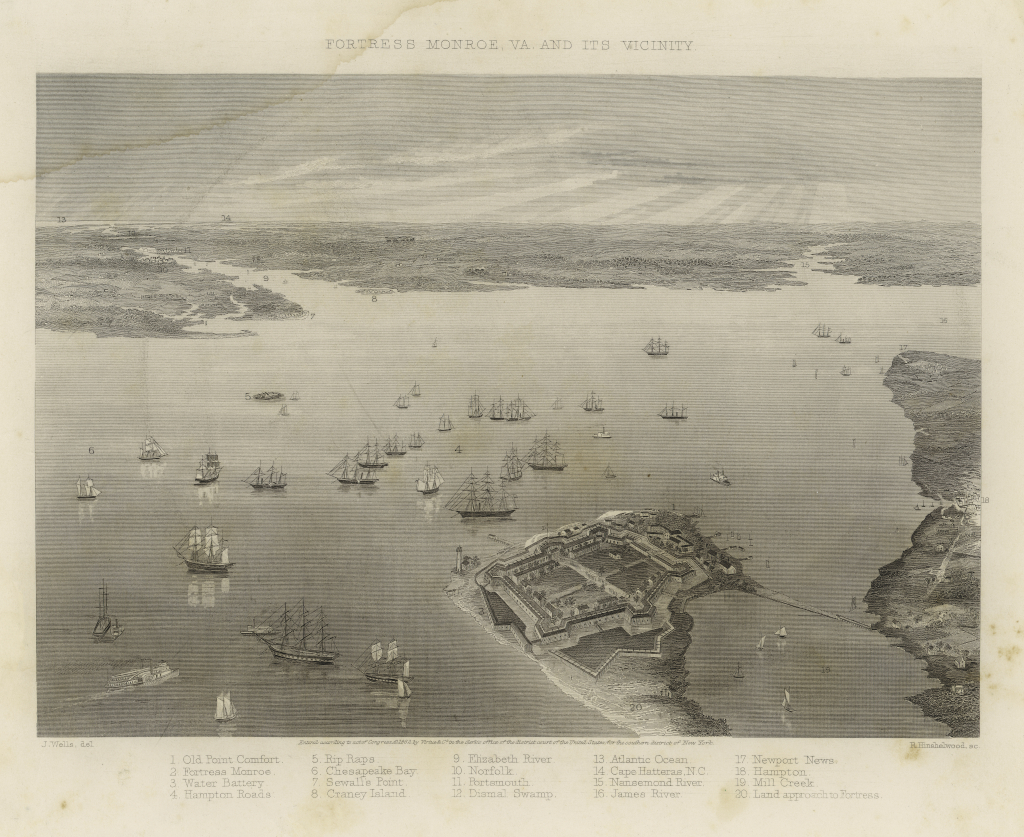

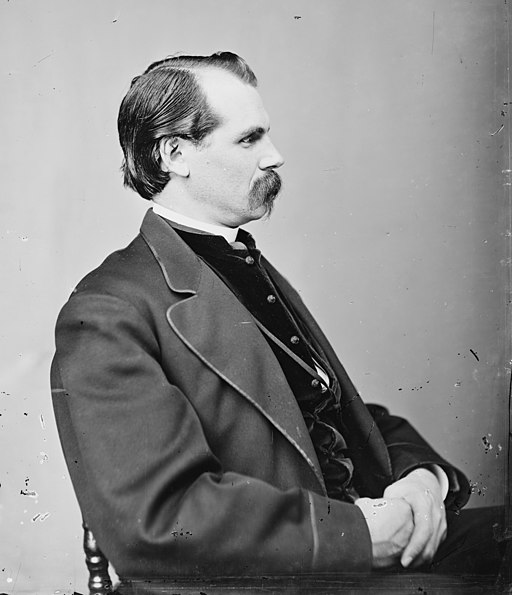

Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler, commander of the Union Department of Virginia, headquartered at Fort Monroe, was anxious about his precise knowledge, or lack thereof, of the actual whereabouts of the Confederate positions surrounding the Union enclave on the Peninsula. The Union general arranged for the famous balloonist, John LaMountain, to come to the Peninsula to serve as the Union’s aerial observer.

LaMountain became an aeronaut in 1859 when he worked with the noted balloonist John Wise. They attempted to cross the Atlantic Ocean in the balloon, Atlantic, leaving from St. Louis, Missouri, on July 1, 1859, but they crash landed in Henderson, New York. Their partnership was later dissolved. LaMountain, who kept the balloon, attempted another long distance flight; but, once again, failed. When the Civil War erupted, LaMountain endeavored to become the chief aeronaut for the Union army. Without any political support, he did not secure that appointment.

LaMountain, the aeronaut, arrived at Fort Monroe on July 25, 1861. Due to high winds, LaMountain was unable to make a successful flight until July 31, when he reached the height of 1,400 feet. From there, he was able to observe a radius of more than 30 miles. His next ascension on August 1, 1861, enabled him to see the Confederate camp at Young’s Mill and to note that this position held between 4,000 and 5,000 men. He also reported that the Confederates had an advanced position on Waters Creek on the Warwick Road as well as fortifications on Sewells Point, Craney Island, and Pig Point.

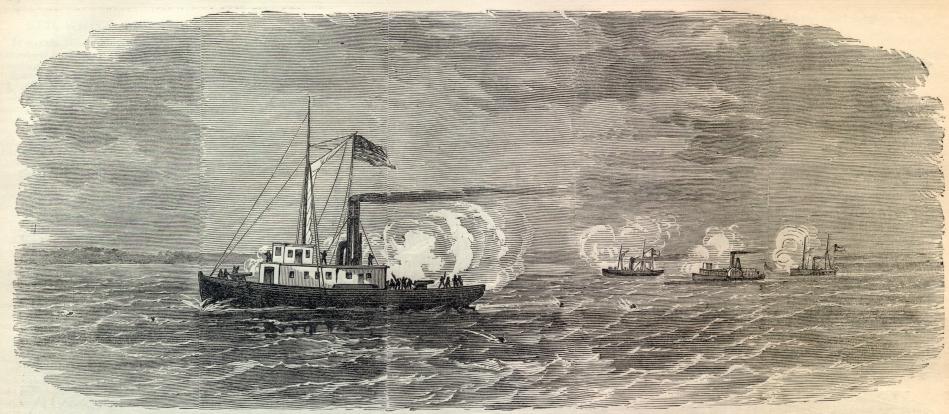

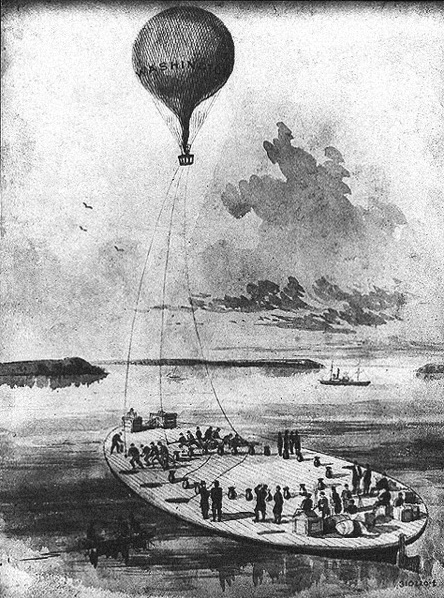

On August 3, 1861, LaMountain lifted his balloon from the deck of the USS Fanny using a windlass and mooring ropes. The balloon reached the height of 2,000 feet and enabled thorough inspection of the Confederate positions defending Norfolk. A second flight was made on August 10 from the deck of the tug Adriatic. La Mountain had by now used all of his hydrogen gas-making materials and needed to secure these supplies from elsewhere. Before he departed Fort Monroe, La Mountain proposed to General Butler that he could return with a balloon capable of destroying Norfolk. LaMountain further advised Butler that “ballooning can be made a very useful Implement in warfare.” [1]

Out of the Sky Comes Professor Lowe

When LaMountain returned to Fort Monroe, Butler had already been replaced by Major General John Ellis Wool who determined he did not need LaMountain’s services. The US Army had named Professor Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe as its chief aeronaut.

Lowe, a native of New Hampshire with only a limited education, became an expert in applied science. He readily took to aeronautics and built his first balloon in 1858. He and his balloons went on tours and he was celebrated throughout the nation. Lowe invented a coal-gas generator to produce hydrogen.

While he twice attempted a cross-Atlantic voyage, his fame increased when he made a nine-hour, 900-mile flight from Cincinnati, Ohio, to Unionville, South Carolina, on April 19-20, 1861, just after the capture of Ft. Sumter. As soon as he landed, he was arrested as a spy. After his release, Lowe rushed to Washington, D.C., to secure his appointment as chief aeronaut of the US Balloon Corps in early July 1861. On June 18, he sent the first telegraph message from a balloon. Shortly after the First Battle of Manassas, Lowe observed Confederate positions south of the Potomac. He became the first aerial observer to fire direction for artillery. [2]

1862 Peninsula Campaign: The Height of Military Aerial Observation

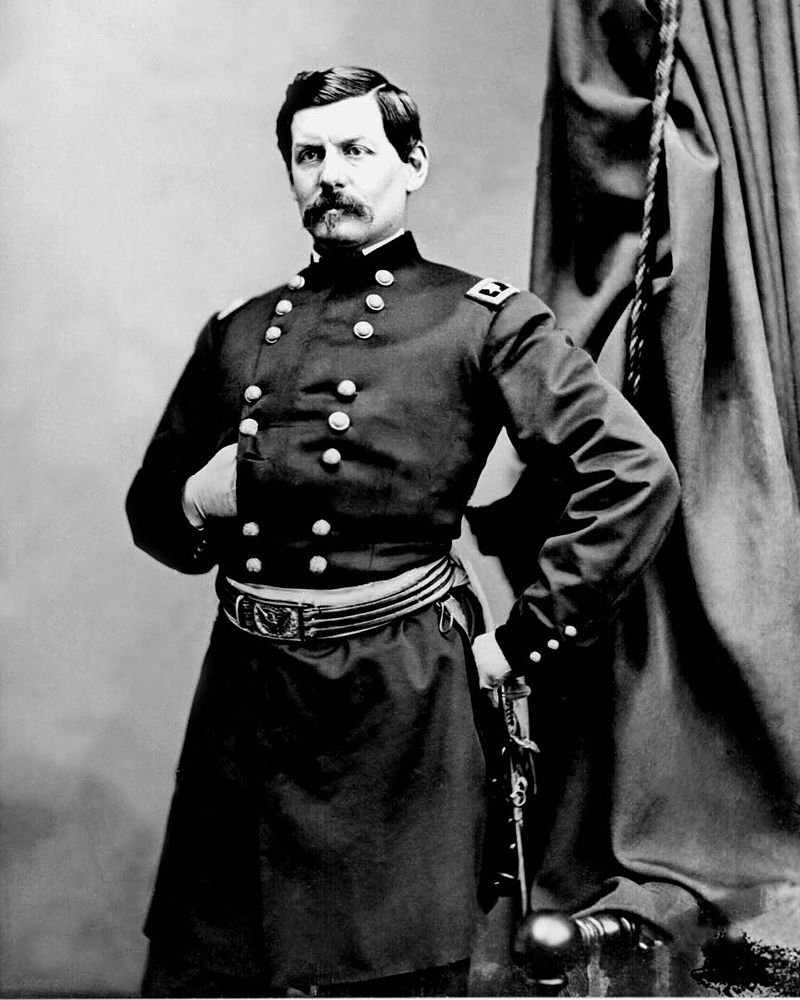

On April 4, 1862, Major General George Brinton McClellan’s 120,000-man Army of the Potomac began its march up the Virginia Peninsula toward Richmond. The next day, the Union army was stopped by Major General John Bankhead Magruder’s Confederate Warwick-Yorktown defensive line and his 13,000-strong army.

Magruder, although outnumbered almost four to one, bluffed McClellan into believing that the Confederates had more than 100,000 soldiers defending the Peninsula. “It was a wonderful thing,” recorded diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, “how he played his ten thousand before McClellan like fireflies and utterly deluded him.”[3]

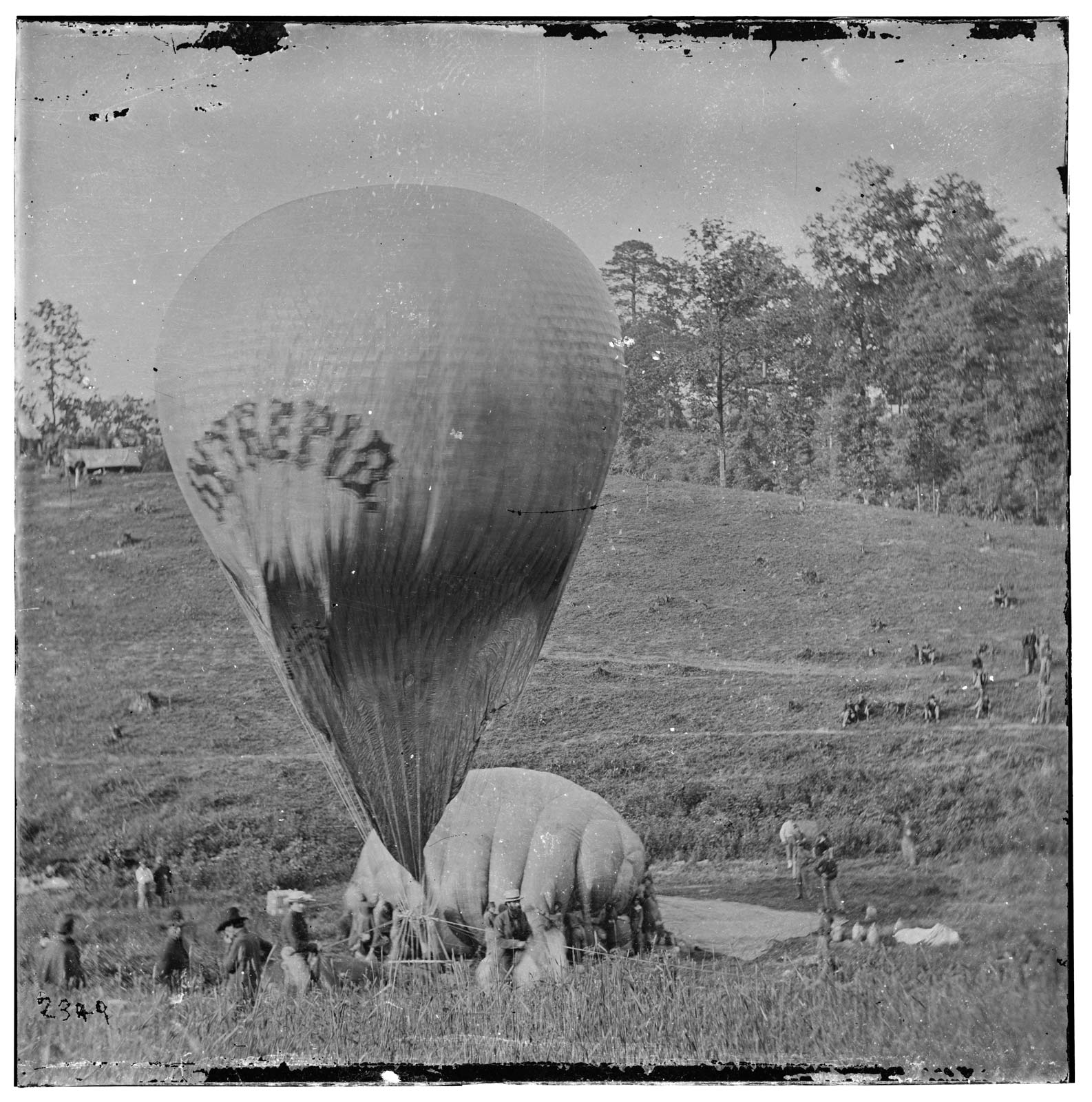

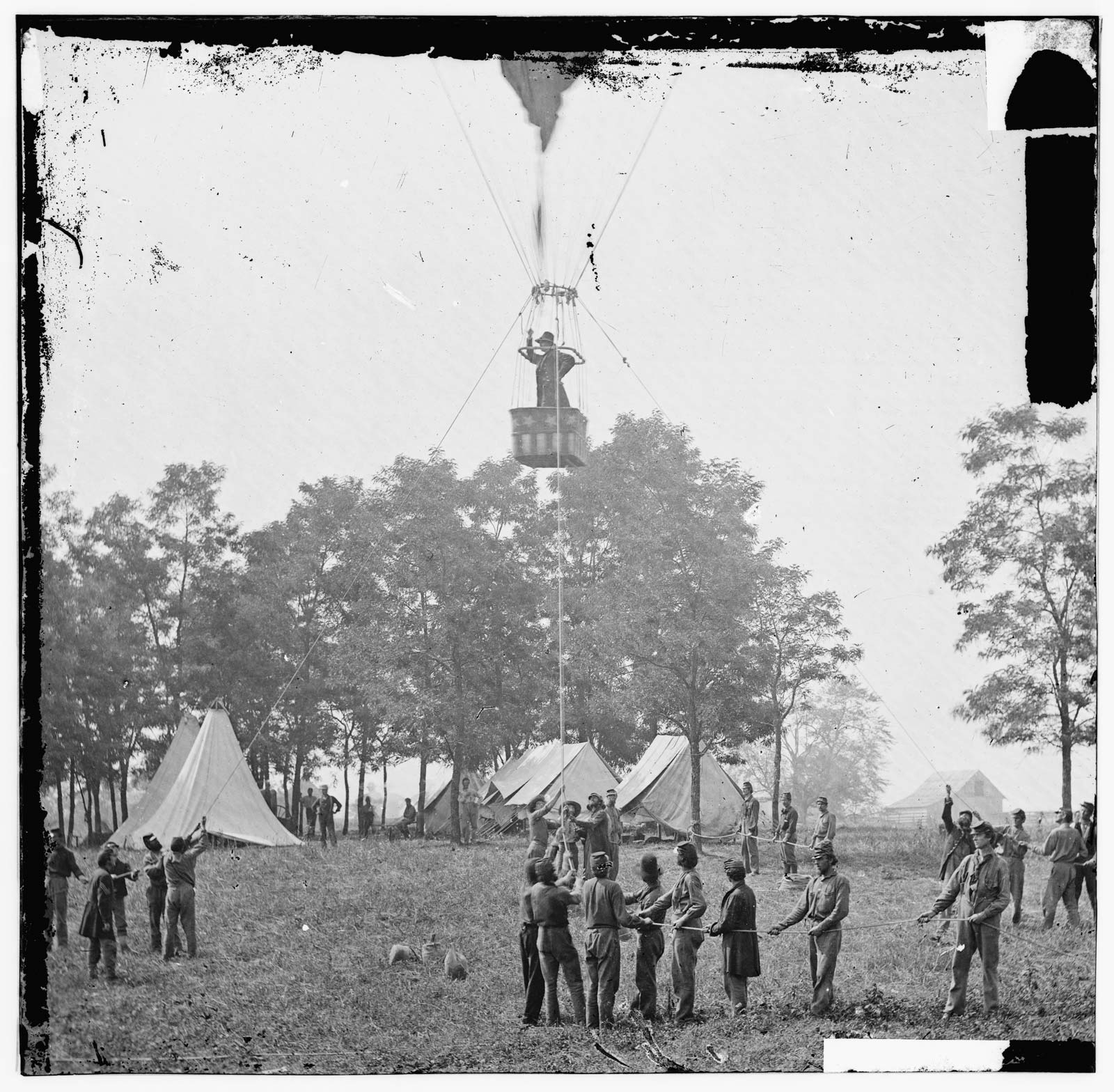

April 6, 1862 was a day of reconnaissance. Thaddeus Lowe’s balloon, Intrepid, made its first appearance over the Confederate lines. Lowe operated his heavily varnished harvest moon orange balloons using a mobile hydrogen gas generator. Lowe had brought two balloons, Intrepid and Constitution, to the Peninsula on his balloon barge, George Washington Parke Custis. The balloons were typically operated using three to four tether ropes and two men, an operator and observer, who would go aloft in a wicker basket festively decorated with star bunting.

The Intrepid was based at Yorktown. Flights became a familiar sight, with Brigadier General Fitz-John Porter taking several trips above the siege lines.

On the morning of April 10, Porter went up in the balloon alone. He had wished to achieve a higher elevation, so only one tether rope was used.

Unfortunately, just as the operator, James Allen, prepared to get into the basket, the rope broke with a loud snap, like the sound of a gunshot, and up went Intrepid, out of control. Porter, who had observed how to operate the balloon, remained calm. As the balloon floated over Confederate lines, he took notes, and when it drifted back over Union lines, he was able to land it safely.

McClellan wrote his wife about the incident: “I am just recovering from a terrible scare. Early this morning I was awakened by dispatch…stating that Fitz had made an ascension in the balloon. That the balloon had broken away & had come to the ground some three miles SW which would have been within the enemy lines. You can imagine how I felt! I was at once off various pickets to find out what they knew & try to do something to save him–but the order had no sooner gone–then in walks Mr. Fitz just as cool as casual–he had luckily come down near my camp after actually passing over that of the enemy!! You may rest assured of one thing; you won’t catch me in that confounded balloon nor will I allow any other generals to go up in it.”[4]

Custer on the Ride of His Life

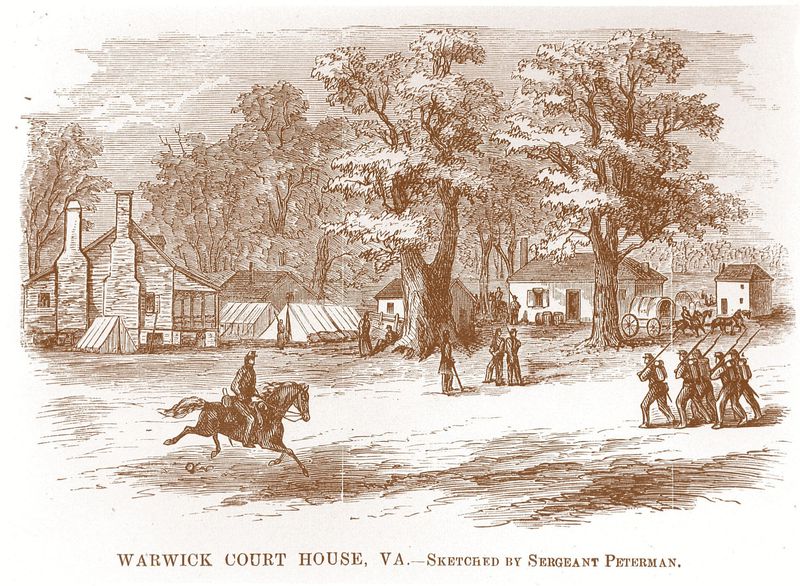

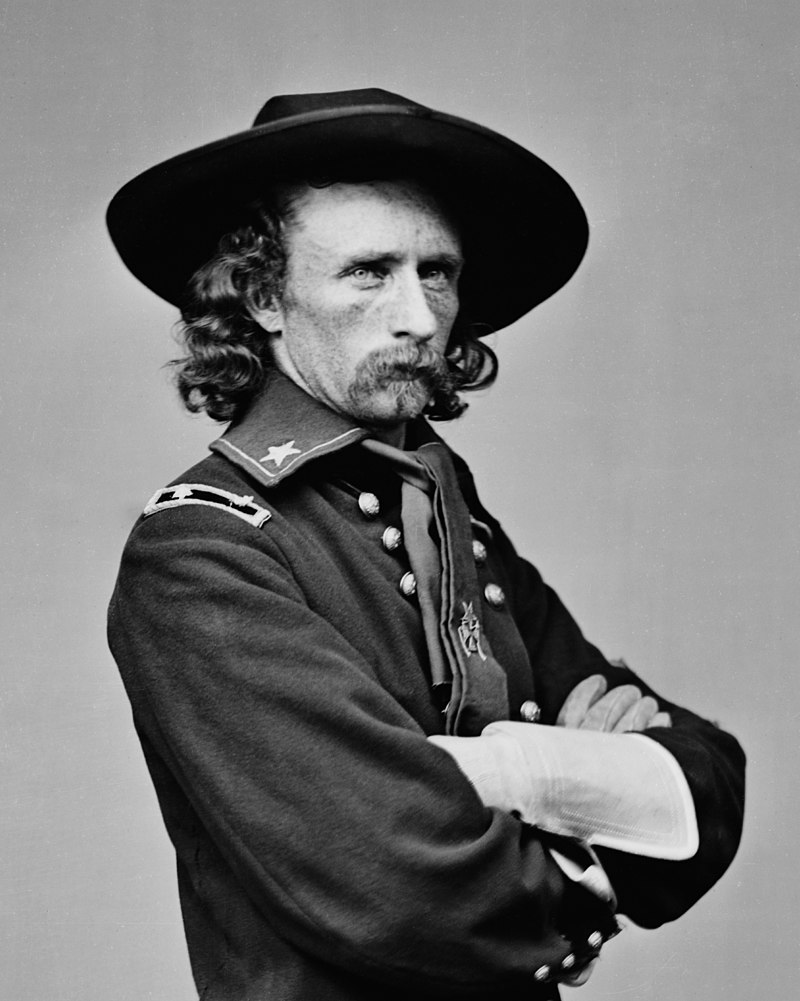

Porter and Brigadier General John Gross Barnard, chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac, continued to make use of balloon observations to aid their locating Union siege-guns. A second balloon camp for the Constitution was established at Warwick CH on April 10. Lieutenant George Armstrong Custer enjoyed the dubious honor of making several ascents in this balloon to observe the Confederate defenses between Lee’s Mill and Dam No. 1.

At first, Custer “ridiculed the system of balloon reconnaissance” when he was ordered to go up in the Constitution with Lowe’s assistant, John Allen. As a cavalryman, Custer thought, “I had a choice as to the character of the mount, but the proposed ride was far more elevated than I had ever desired or contemplated.” When asked by Allen if he wished to go up in the balloon alone, Custer replied that his desire, “if frankly expressed would not have been to go up at all.”

Custer was nervous about the basket construction and as the balloon rose into the sky, the young lieutenant noted, “I was urged to stand up also. My confidence in balloons at that time was not sufficient however to justify such a course so I remained in the bottom of the basket with a firm hold on either side.” Once the Constitution had reached the proper attitude altitude, Custer was able to overcome his fears and stood up to make observations. He recounted, “To the right it could be seen the York River, following which the eye could rest on the Chesapeake Bay. On the left at about the same distance flowed the James River…Between these two rivers extended the most beautiful landscape, and no less interesting than beautiful.”

Custer recorded the Confederate positions below him at the “point over which the balloon was held was probably one mile from the nearest point of the enemy’s line. In an open country balloons would be invaluable in discovering the location of enemy camps and works. …The enemy camps like our own were generally pitched in the woods…the earthworks along the Warwick River were also concealed by growing timber. Here and there the dim outline of an earthwork could be seen more than half concealed by the trees which have been purposely left standing on their front. Guns can be seen mounted and peering sullenly through the embrasures, while men in considerable numbers were standing in and around the entrenchments, often collected in groups, intently observing the balloon, curious, no doubt, to know the character or value of the information its occupants could derive from their elevated post of observation.”[5]

Though Custer took several flights, he could never accurately estimate Confederates defending to prove or disprove Allen Pinkerton’s reports that more than 100,000 soldiers were supporting the Warwick-Yorktown defenses. Pinkerton, who would gain a grand reputation for prewar detective work, set up the Secret Service, after the First Battle of Manassas. Using contrabands and deserters, he presented McClellan with a high valuation of Confederate troop strength that only supported the Union general’s belief, based on his scholarship about sieges, that Magruder would have only defended the Warwick-Yorktown line if he had at least 100,000 men per mile. Nevertheless, Lowe’s balloons were extremely helpful as the Federal officers developed their siegeworks and built batteries to eventually bombard Yorktown.

The Confederates Fly Back

The Confederates responded, not only with artillery (cannons, elevated by the Confederate artillerist Edward Porter Alexander, to serve as anti-aircraft guns), but also with their own balloon. It was a roughly made hot air device rather than Lowe’s gas type, and was commanded by one of Magruder’s aides, John Randolph Bryan of Gloucester County, Virginia. Actually, Bryan had volunteered for a special assignment and was surprised to learn from General Joseph Eggleston Johnston at his temporary Lee Hall headquarters that flying in a balloon was to be his reconnaissance duty. Bryan protested at first, noting “I have never even seen a balloon, and I knew absolutely nothing about the management of it.”

On a flight, as the balloon rose up above the treetops, Bryan remembered how the Federal shells and bullets “whistled and sang…a most unpleasant music” around him.[6] “Yesterday, the rebels sent up a balloon directly in front of us,” New York artillerist David Ritchie commented from Warwick CH, “but it was not in the air more than five minutes when it suddenly descended much faster than it rose, having received a sharpshooter’s bullet.”[7]

The Confederate balloon was never struck by enemy fire, however, and Bryan made several flights from Lee Hall, Wynnes Mill, and Yorktown to observe Federal siege preparations. Even though Bryan made his subsequent aerial observations “with somewhat less trepidation,” the young aeronaut’s last voyage nearly resulted in disaster when a severed tether rope sent him off on a free flight. Bryan remembered how “the balloon jerked upward by great force for about two miles or it seemed to me. I was breathless and gasping and trembling like a leaf from fear without knowing what had happened beyond the surmise that the rope which held me to the earth had broken.”

The Confederate aeronaut was blown over the camp of the 2nd Florida Regiment. The Confederates mistook Bryan’s balloon for a Federal spy device and began shooting at him. The balloon then drifted over the York River and “began to settle quite rapidly,” Bryan recalled: “It was evident that I would be dumped in the middle of this broad expanse of water.” Bryan stripped off his clothes and boots preparing for a swim. He could hear the tether line on the water when another breeze blew the balloon back over the banks of the York River and he landed near an apple orchard. It was Bryan’s last flight.[8]

The End of Civil War Aerial Observation

Bryan’s balloon was then transferred onto the CSS Teaser. This former tug, commanded by Lieutenant Hunter Davidson, was armed with one 32-pounder rifle and one 12-pounder howitzer. It also had onboard electronic torpedo equipment. On July 4, 1862, the Teaser was attacked by the ironclad USS Monitor and the gunboat USS Maratanza. The Maratanza’s first shot was high; however, the next shot of canister forced the Southerners to abandon their ship. Accordingly, this marked the end of the Confederate air force.[9]

Time was also running out for Professor Lowe’s balloon corps. Lowe had supported McClellan’s army throughout the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles. He had proved the value of aerial reconnaissance with the important information he gleaned from the sky. Nevertheless, Lowe fell out of favor with later commanders of the Army of the Potomac. He resigned his position as chief aeronaut on May 8, 1863.[10] Observation balloons would not return to the Virginia Peninsula until World War I.

ENDNOTES

1.Chester D. Bradley, “The Fanny: First Aircraft Carrier,” vol. 2. Ft. Monroe, VA: Casemate Chronicles, 1968.

- Patricia L. Faust, ed., Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War. New York: Harpers Perennial, 1991, pp. 451-452.

- C. Vann Woodward, ed., Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981, p. 401.

- Stephen Sears, ed., The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, New York: Da Capo Press, 1992, p. 235.

- George Armstrong Custer, “War Memories.” The Galaxy—A Magazine of Entertaining Reading, 22, 1876.

- John Randolph Bryan, “Balloon Used for Scout Duty in CSA.” Southern Historical Society Papers, 33, April 1914, p. 33.

- Norman L. Ritchie, Four Years in the First New York Light Artillery: The Papers of David R. Ritchie. Hamilton, NY: Edmonston, 1997, p. 43.

- Bryan, pp. 34-35.

- Robert W. Daly, ed., Aboard the Monitor: 1862: The Letters of Acting Assistant Paymaster William Frederick Keeler, US Navy, to His Wife Anna. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1962, p. 184.

- Faust, pp. 451-452.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bradley, Chester D. “The Fanny: First American Aircraft Carrier,” vol. 2. Ft. Monroe, VA: Casemate Chronicles,1968.

Bryan, John Randolph. “Balloon Used for Scout Duty in CSA.” Southern Historical Society Papers, 33. April 1914. Richmond, Virginia.

Custer, George Armstrong. “War Memories.” The Galaxy–A Magazine of Entertaining Reading, 22, November 1876.

Daly, Robert W., ed. Aboard the Monitor: 1862: The Letters of Acting Assistant Paymaster William Frederick Keeler, US Navy, to His Wife Anna. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1962.

Faust, Patricia L., ed. Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991.

Ritchie, Norman L., ed. Four Years in the First New York Light Artillery: The Papers of David R. Ritchie. Hamilton, NY: Edmonston, 1997.

Sears, Stephen, ed. The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan. New York: DaCapo Press, 1992.

Woodward, C. Vann, ed. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992.