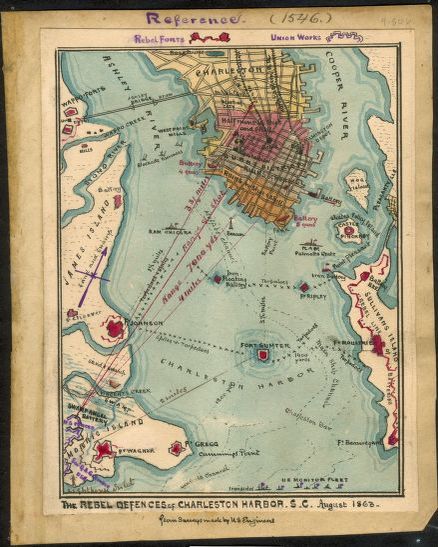

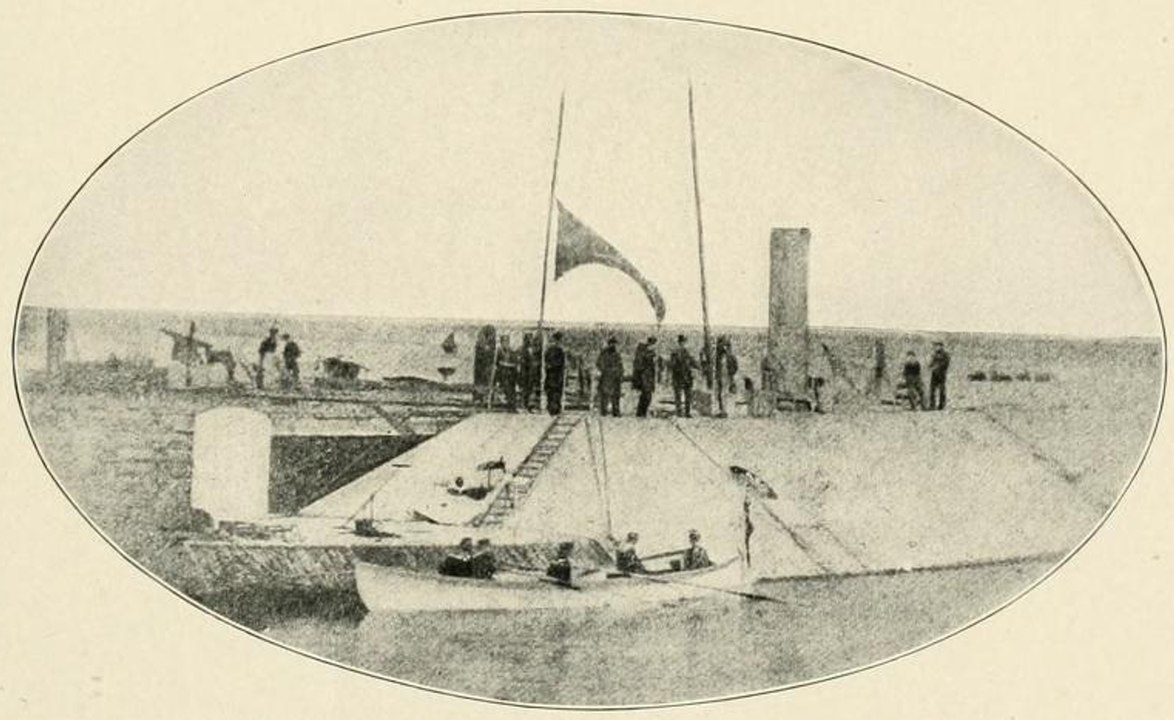

Something unusual occurred in the early morning darkness of January 31, 1863, when the Confederate ironclad rams, CSS Chicora and CSS Palmetto State, crossed the Charleston Bar and struck the Union ships guarding that blockade runners’ haven. It was the first time that Confederate ironclads had entered the open sea and, in the opinion of Confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard, had broken the blockade. While the Federal gunboats were quickly back on station, it was a great boost to the defenders of Charleston who were expecting a Union ironclad attack on their harbor.

Robert Knox Sneden, artist, 1832-1918. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

ca. late 1861. The Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes:

Volume One, The Opening Battles, 1911. Public domain.

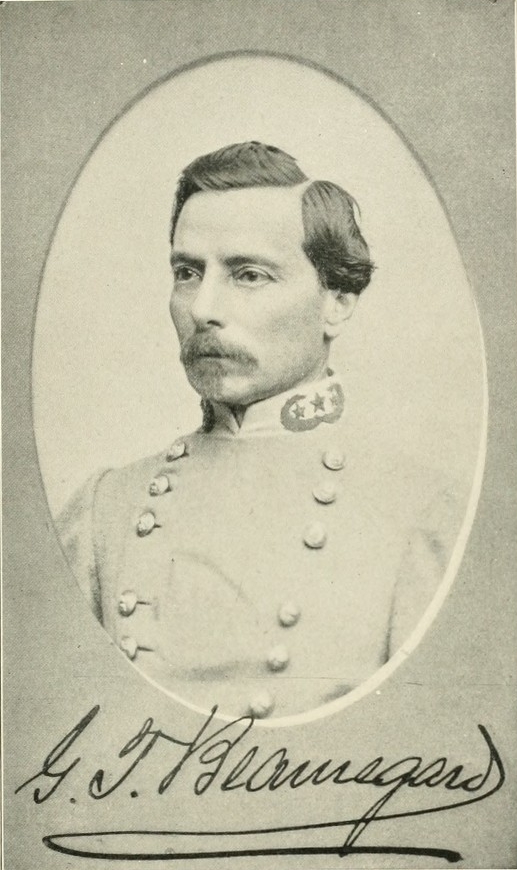

When General P.G.T. Beauregard assumed command of the Department of South Carolina and Georgia on September 24, 1862, he immediately realized the need for active support of the Confederate navy in order to defend harbors like Charleston and Savannah. Beauregard, the hero of Fort Sumter and the Battle of First Manassas, knew that ironclad rams armed with rifled cannon offered the best opportunities not only to protect harbors; but also, to perhaps break the Union stranglehold on Confederate commerce — the cotton for cannon trade so important for the Southern war effort.

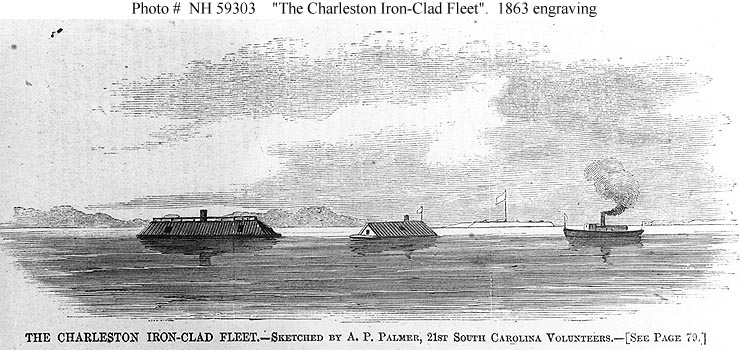

Charleston Squadron

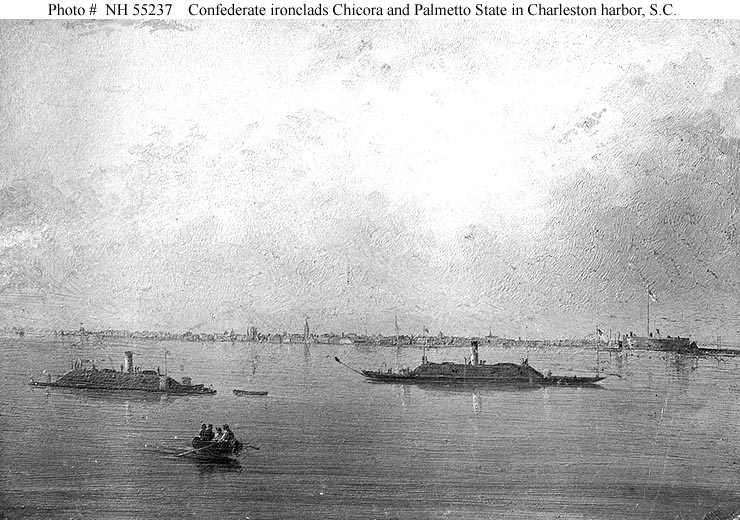

The power of iron over wood was clearly recognized by Charlestonians. The impact of the loss of Port Royal Sound was deeply felt. Many rationalized that had a Confederate casemate ironclad been there, that Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron may have been repulsed in November 1861. Accordingly, the South Carolina government authorized the construction of two Richmond-class ironclads designed by Chief Naval Constructor John Luke Porter.

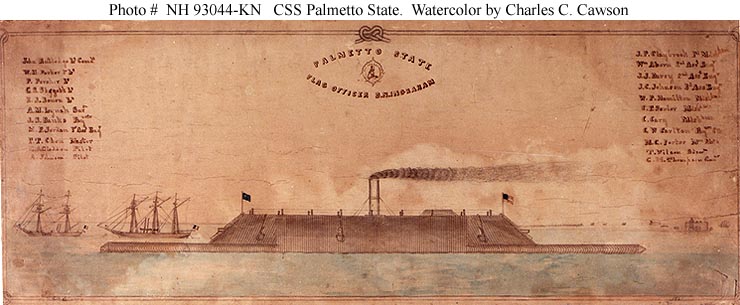

The first to be placed under construction in January 1862 was CSS Palmetto State by the shipbuilder Cameron & Co. in Charleston, SC. This ironclad’s dimensions were:

Length 150 feet

Beam: 34 feet

Draft: 12 feet

Armament: two 7-inch Brooke rifles and two IX-inch Dahlgren shell guns

Machinery: 1 screw

Crew: 180

Speed: 6 knots

Armor: 4 inches iron with 22 inches of oak and pine backing

Then, on April 25, 1862, the CSS Chicora was laid down at James M. Eason’s Charleston shipyard. This ironclad was bigger than Palmetto State. Its characteristics were:

Length: 172 feet, 6 inches

Beam: 35 feet

Draft: 14 feet

Armament: two IX-inch Dahlgren shell guns and four 32-pounder banded rifles

Machinery: 1 screw

Crew: 180

Speed: 5 knots [1]

From The Photographic History of The Civil War in Ten Volumes: Volume Six, The Navies. The Review of Reviews Co., New York. 1911. p. 239.

Public Domain.

As with most Confederate ironclads, both Palmetto State and Chicora were underpowered as they were refitted from smaller steamers. The rams could barely make 5 knots under the best of circumstances and sometimes had difficulty holding their position with a flood tide.

Nevertheless, Lieutenant William H. Parker, executive officer of Palmetto State, thought: “when these two ships had been in commission a short time, they were fine specimens of men-of-war and would have done credit for any navy….They were the cleanest iron-clads that ever floated, and the men took great pride in keeping them so.”[2]

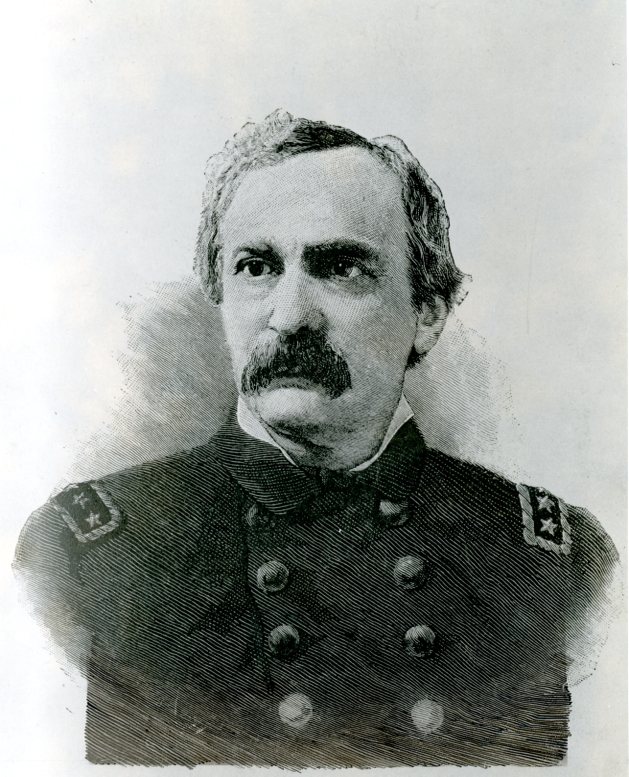

Veteran Leaders from the Battle of Hampton Roads

Parker had commanded the CSS Beaufort in the North Carolina Squadron and during the Battle of Hampton Roads. Other outstanding officers in the Charleston Squadron included Commander John Randolph Tucker and Flag Officer Duncan Ingraham. Ingraham, the squadron commander, was a hero of the War of 1812. Tucker, commander of CSS Chicora, had joined the US Navy in 1826; he had commanded CSS Patrick Henry during the Battle of Hampton Roads. The Charleston Squadron enlisted men who were among the best of any Confederate squadron, including the crew of the ill-fated ironclad CSS Arkansas, as well as three African American sailors. It was said that they were well-trained and well disciplined. [3]

Grand Strategy

Beauregard was not impressed by the two new rams; however, he was fortunate to have them ready for service in November 1862. The Confederate general wanted to use these ironclads to attack the Union blockaders before Union ironclads arrived at Port Royal Sound. Beauregard did not believe that the Charleston ironclads could fight one on one against the new Passaic-class monitors. He also knew that the monitors would soon be off the entrance to Charleston harbor and that the Federals were planning a major attack against the city. So, this was the only chance to damage Federal ships and break the blockade. If the Confederates could raise the blockade for 24 hours, then the British and French would hopefully proclaim the blockade broken, forcing the Federals to formally reestablish it.

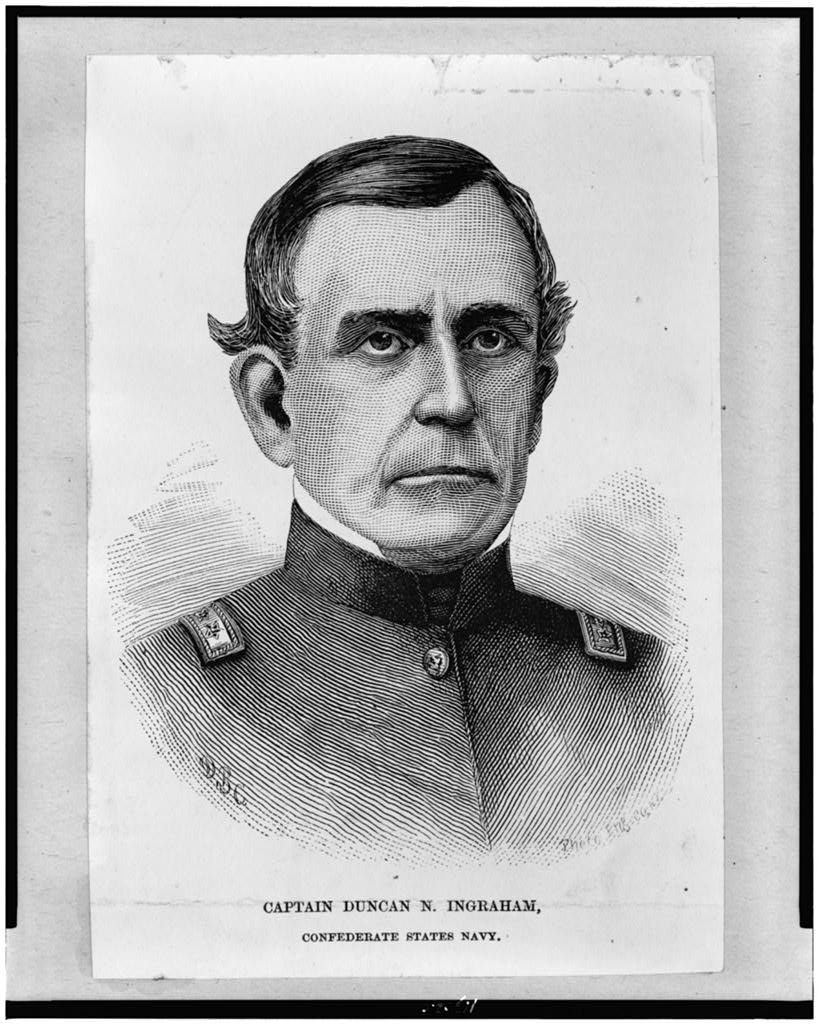

Bust portrait, facing front / D.B.C. ; photo. Eng Co. NY. , None.

[Between 1861 and 1865]

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Ingraham protested this plan of action as he knew that his ironclads were for coastal defense only and were too top heavy to go to sea. Beauregard insisted that an attempt had to be made. Bad weather delayed the sortie until the evening of December 30. Flag Officer Ingraham then thought it was the right time to attack. The Palmetto State got underway at 10 a.m., followed by the Chicora 15 minutes later. The rams were supported by three steam tugs: General Clinch, Etowan, and Chesterfield. It was an 11-mile voyage to the other edge of the harbor. At 4:30 a.m., the two ironclads crossed the bar at high tide and steamed toward a blockader looming ahead in the mist. [4]

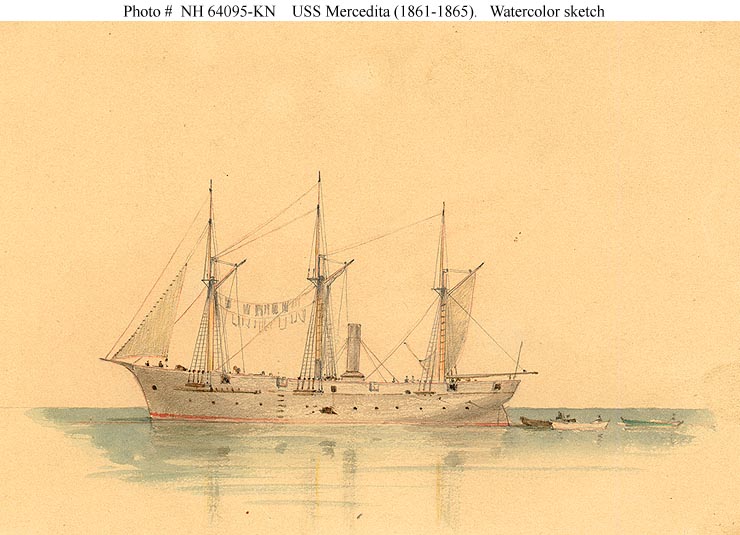

Capture of USS Mercedita

Flag Officer Duncan Ingraham ordered the commander of Palmetto State, Lieutenant Commander John Rutledge, to go directly for the first ship, the USS Mercedita. This screw powered warship was armed with eight 32-pounders and one 20-pounder rifle and could make 14 knots. It was commanded by Captain Henry S. Stellwagen.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 44332

The Mercedita had just chased a troop ship that Stellwagen thought might be a blockade runner. This arduous chase prompted him to retire to his quarters. Moments later, the steamer’s executive officer, Lieutenant Commander Trevett Abbot, was ringing the alarm that a ship was rapidly approaching. No Union guns could be fired because the ironclad was so close and had such a low profile. Panic ensued aboard Mercedita. [5]

Watercolor sketch, probably made during the Civil War. Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 64095-KN

Abbot hailed the unknown vessel and was told, “This is the Confederate steamer PALMETTO STATE.” Immediately thereafter, the ironclad rammed Mercedita. A shell was fired which entered a few feet above the waterline on the starboard side. It crashed through Mercedita’s boiler and condenser, and then completed its destructive path, blowing a 4-foot hole in the steamer’s port side. This sent scalding steam throughout the Union ship, leaving Mercedita dead in the water. It appeared the vessel was sinking. [6]

Unstoppable Ironclads

Captain Stellwagen believed he had no choice but to surrender his ship. He had not even fired a shot at the Confederate ironclad. Lieutenant Commander Abbot went over to Palmetto State to seek assistance, relief, and terms. Ingraham “regretted that…he had no room to accommodate” the Union crew. Ingraham demanded that Abbot give parole of honor so that the officers and crew of Mercedita would not “take up arms against the Confederate States during the war, unless legally and regularly exchanged.”[7]

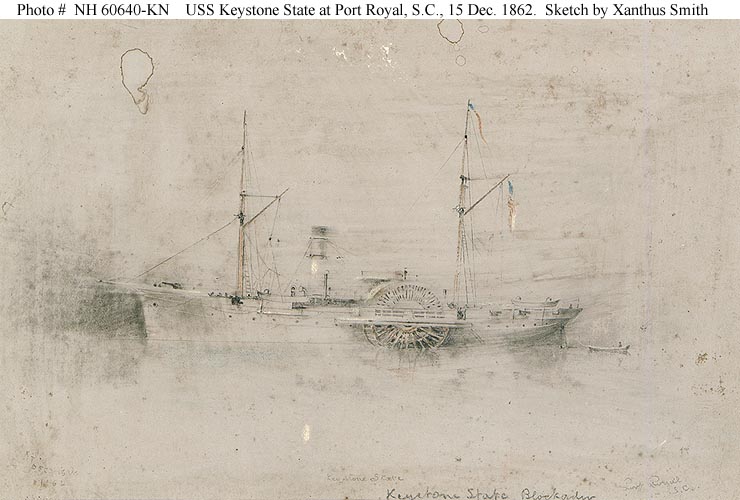

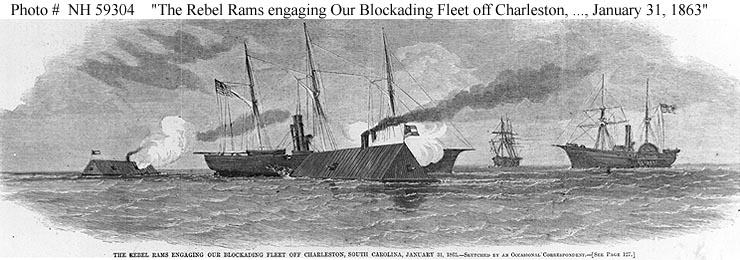

Meanwhile, the Chicora headed toward USS Keystone State. This Union sidewheeler was built in 1853 and acquired by the US Navy in 1861. The warship could make 9.5 knots using a side-lever engine. With a complement of 163 officers and crew, Keystone State was armed with four 12-pounders, one 150-pounder rifle, two 32-pounders, and two 30-pounder rifles. [8] The paddler was commanded by William E. Le Roy. He was nicknamed ‘Lord Chesterfield’ for his insistence on “good breeding and gentlemanly bearing” and was a “great stickler for red tape…and easily excited.”[9]

Colored pencil sketch by Xanthus Smith.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command.

At 5 a.m., Le Roy heard a shot fired and immediately had his crew beat to quarters. He believed it was an announcement that a blockade runner had been sighted. Soon Keystone State noticed that a steamer was approaching that looked ‘suspicious’ and the sidewheeler opened fire. The Chicora returned fire. A shell rumbled through Keystone State’s berth deck, killing and wounding several men; it also started a fire. Le Roy believed he was being attacked by both Palmetto State and Chicora. He later wrote, “it was discovered there was one on either quarter, and we made them out from their peculiar construction to be ironclads after the model of the MERRIMACK.” Le Roy attempted to put out the flames by steaming into the wind at his highest speed. This action put out the fire in the forehold. [10]

The Tide Will Tell

The Keystone State then came about in about 10 minutes. Le Roy, with pressure values tied down, decided to ram Chicora. When the two warships reached within about 500 yards or so, a shell from the Confederate ironclad hit Keystone State on the port side passing through both steam drums. Steam hissed through the sad ship as Chicora continued to shell the Federal sidewheeler. Le Roy thought that Keystone State was doomed with no motive power, the ship filling with water, several fires burning, and more than 40 casualties. He ordered the US flag to be lowered in an act of surrender. But the ship’s commander learned he still had power in one wheel and could move away from Chicora.[11]

Line engraving, “Harper’s Weekly,” Jan. – June 1863, p 117. CSS Chicora and CSS Palmetto State attack USS Mercedita; USS Keystone State at right. Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 59304

Soon other blockaders arrived on the scene. The USS Memphis was able to tow the damaged Keystone State to safety. The USS Quaker State came too close to Chicora and received a shell into its engine room. The other ships did not attempt to test the ironclads and stayed out of range. When Flag Officer Ingraham realized that all of the Federal ships were out of sight, at 8:45 a.m., he ordered his ships to move under the cover of batteries on Sullivan’s Island to await the next high tide. By 4 p.m., the ironclads had crossed the bar into Charleston harbor. As they passed the Confederate batteries, guns were fired, and cheers were raised in honor of the successful action achieved by Palmetto State and Chicora.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command NH 55237

A Good Day for Confederate Ironclads

It had been a perfect day for the Confederate ironclads to make their assault. Flag Officer Ingraham reported, the “sea was perfectly smooth, as much so as in the harbor; everything was most favorable for us and gave us no opportunity to test the sea qualities of the boats. The engines worked well and we obtained a greater speed than they had ever before sustained.” While the Confederates did not sink any Union vessels, the ironclads did severely damage two blockaders and injured another. Ingraham noted, “We had but little opportunity of trying our vessels, as the enemy would not close.” [12]

The victory was quickly announced by General Beauregard and he quickly telegraphed Confederate Secretary of State Judah Benjamin that the Union ships off Charleston had been scattered. Benjamin publicly proclaimed the blockade broken; however, it was not to be. The Union fleet was soon back on station as the Federals’ stranglehold on the Confederate coastline continued.

The Confederate ironclads performed rather well during this excursion. Their limited speed did not allow them to close on any more Union ships other than the two — Mercedita and Keystone State — that they surprised at the action’s beginning. Confederate firepower proved to be far more accurate and effective than that of the Federals as no Southern ship was struck by a Union shot. The Union’s new monitors would soon arrive to strengthen the Union blockade; nevertheless, this first and last excursion of the Charleston Squadron was a blaze of glory.

ENDNOTES

1 Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies: 1855 to 1883, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001, 154-155.

2 William Harwar Parker, Recollections of a Naval Officer, New York: Charles Scribner’s’ Sons, 1883, pp. 193-194.

3 William N. Still Jr., Iron Afloat: The Story of Confederate Armorclads, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1985, 114.

4 J. Thomas Scharf, History of the Confederate Navy: From Its Organization to the Surrender of Its Last Vessel, New York: Gramercy Books, 1996, 676.

5 Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of Rebellion, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901, Ser. I, Vol. 13, 577. [Hereafter referred to as ORN.]

6 Ibid.

7 Scharf, pp. 676-677.

8 Silverstone, 51.

9 Still, 121.

10 ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 13, 582.

11 Ibid.

12 Scharf, 679.