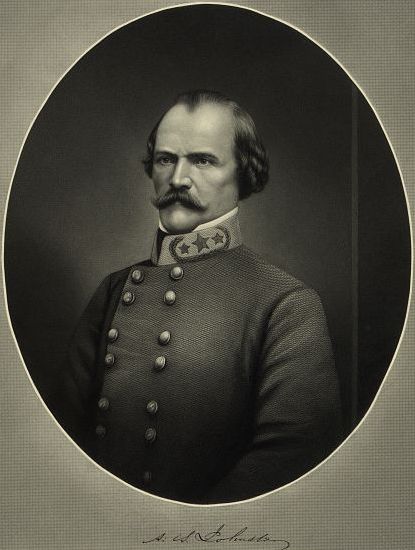

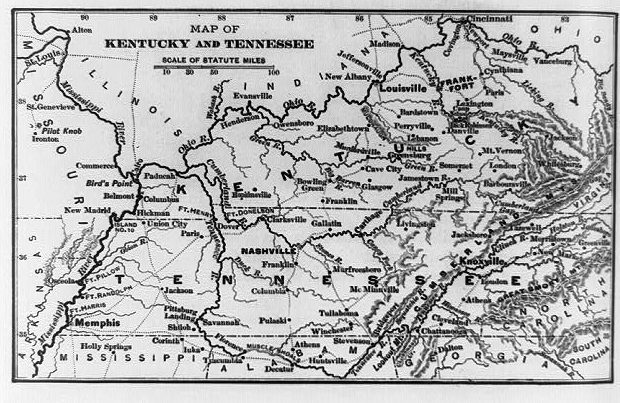

General Albert Sidney Johnston, commander of Confederate forces in Kentucky and Tennessee, planned to defend eastern, middle, and western Tennessee using a series of forts to protect Union access to the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers. Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant and Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote attacked and captured Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River in a bold move. This forced the Confederates to abandon Kentucky and much of Tennessee and opened the door into the Deep South. This campaign began the Civil War career of ‘Unconditional Surrender’ Grant.

Confederate Defenses

Confederate president Jefferson Davis believed General Johnston to be the most outstanding soldier in America. They had studied at West Point, and fought during the Mexican War. together. Johnston realized that he did not have enough troops to block any Union advance effectively.

Confederates attempted to defend Tennessee with fortifications. Major General Leonidas Polk had occupied Columbus, Kentucky, and controlled it with 12,000 men stationed on bluffs commanding the Mississippi River. This was a primary defensive position with a chain blocking the river to Union commerce and naval activity, and more than 140 heavy cannons. Brigadier General Lloyd Tighman maintained the center with 4,000 men at Forts Henry and Donelson. Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner was in command at Bowling Green, Kentucky, with 4,000 men. [1]

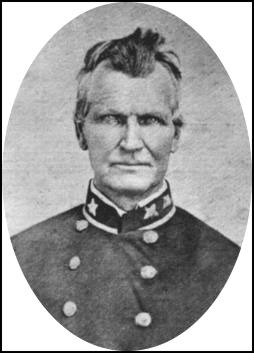

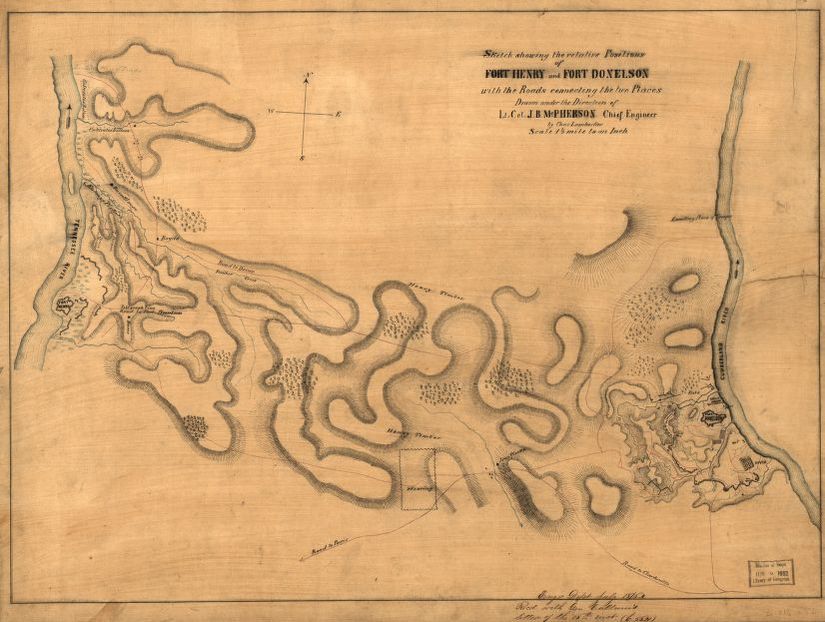

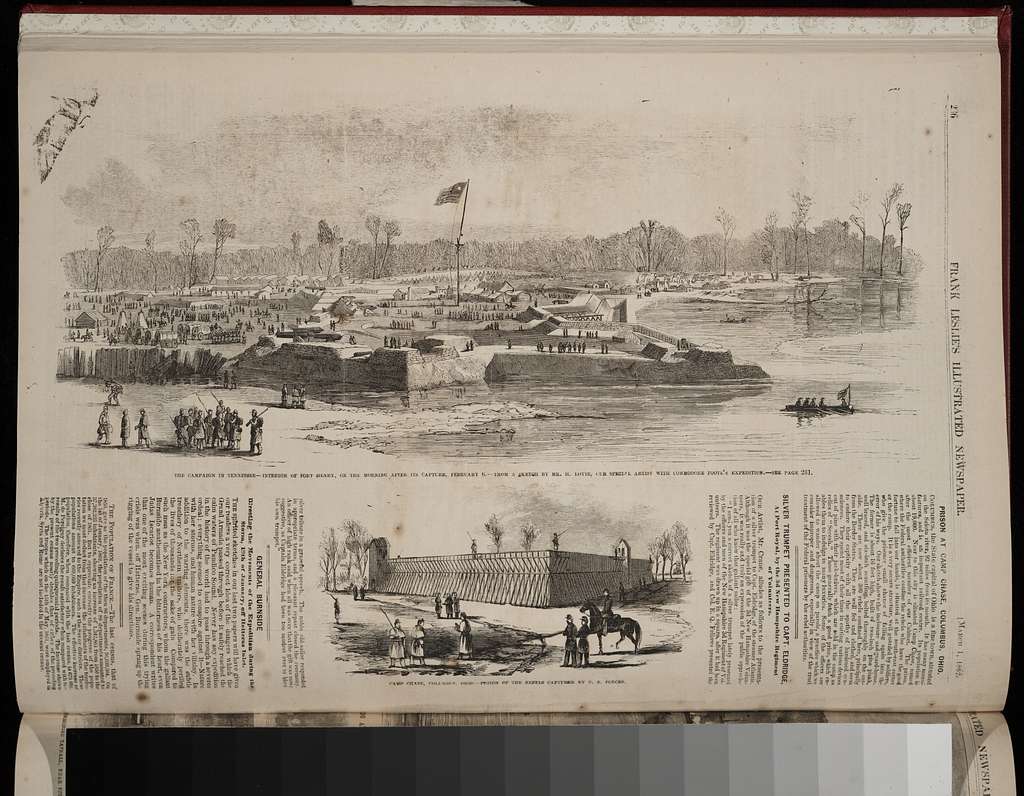

Everywhere seemed open to attack; however, central Tennessee was extremely vulnerable to attack. Union gunboats gave the Federals excellent mobility using the rivers that flowed from north to south. Accordingly, the governor of Tennessee, Isham Harris, ordered Brigadier General Daniel Smith Donelson to select sites for forts on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.

Donelson was an 1825 graduate of West Point, nephew of President Andrew Jackson, and, in 1861, Speaker of the Tennessee House of Representatives.[2] He thought the best sites to build fortifications were in Kentucky; nevertheless, he sited Fort Henry on the Tennessee River’s eastern bank near Kirkman’s Old Landing between Panther Creek and Big Sandy River. Named for Tennessee senator Gustavus Henry Sr., this was a five-sided earthwork built right along the river.

Fort Heiman, across the river in Kentucky, named for prewar architect and Mexican War veteran Colonel Adolphus Heiman. Both of these earthworks were still incomplete in early February 1862. Fort Henry was armed with 17 guns, including ten 32-pounders, two 42-pounders, a rifled 24-pounder, a 10-inch Columbiad, and several smaller cannons to defend the fort’s land face. The fortress was poorly situated as it was located in the river’s flood plain. [3]

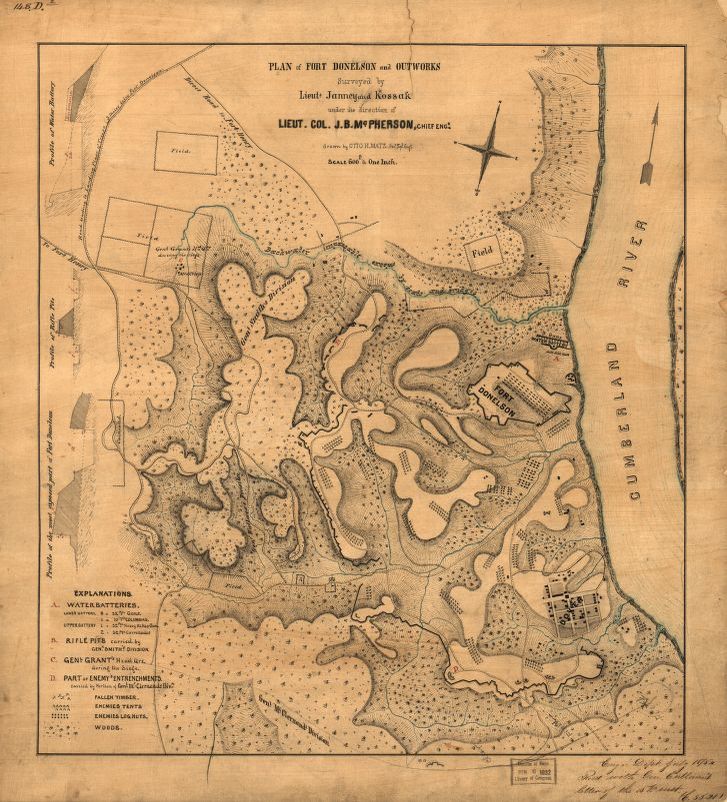

Donelson also selected the site for Fort Donelson. This fort was 12 miles east of Fort Henry near Dover, Tennessee, on the Cumberland River. It covered 97 acres of earthworks, 1,040 feet wide. The land face protected two water batteries made of coffee bags situated on a bluff above the river. The lower battery had nine 32-pounders and one 10-inch Columbiad. The upper battery included two 32-pounder carronades and one rifled 32-pounder. These positions commanded a bend in the Cumberland River. [4]

Federal High Command

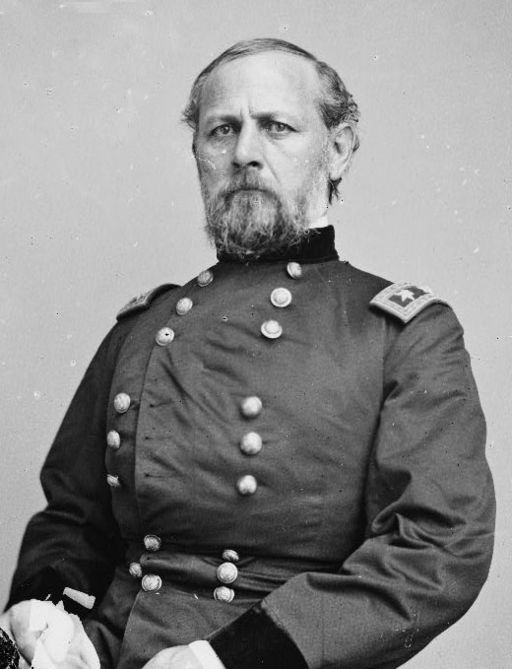

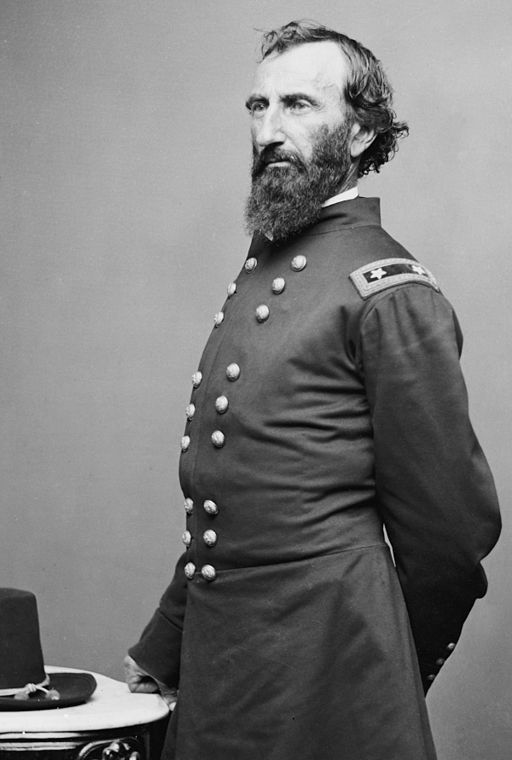

When Major General George B. McClellan was named general-in-chief of the US Army in November 1861, he quickly formulated plans to conquer Tennessee and liberate Kentucky from Confederate control. The region was divided into three districts; however, it would be the Department of Missouri, commanded by Major General Henry Wager Halleck that was supposed to move down the Mississippi. The Department of Ohio, commanded by Don Carlos Buell, would take the initiative in Tennessee.

Buell was an 1841 graduate of West Point, and had served with distinction during the Mexican War, and was severely wounded during the battle of Churubusco. After the war, Buell became a staff officer as an adjutant general for various military departments until named brigadier general of volunteers in May 1861. McClellan promoted him to major general and wanted Buell to move against Knoxville, Tennessee. Instead, Buell suggested his army should move against Nashville. [5]

New Western Commanders

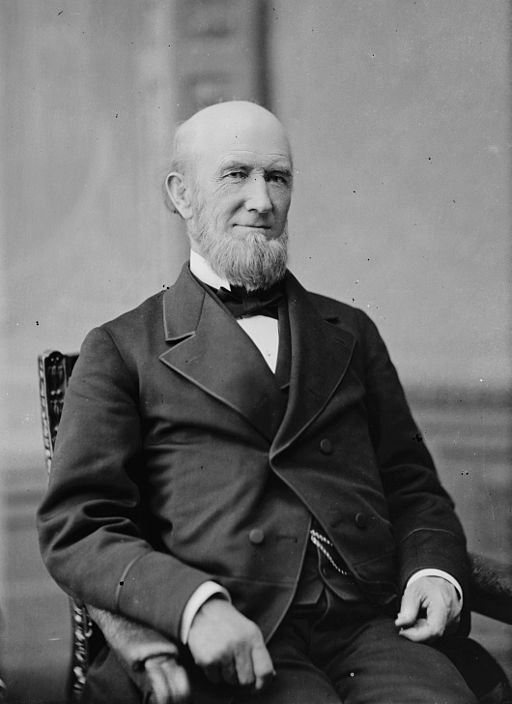

McClellan then replaced the politically motivated and military incompetent Major General John C. Fremont with Major General Henry W. Halleck as commander of the Department of Missouri. Halleck attended Union College, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He graduated from West Point, third in his class, in 1839. He was an assistant professor while still an undergraduate at USMA. In 1844, he toured the defenses of France and then wrote Report On The Means Of National Defense. He later published Elements Of Military Art And Science. While en route to California around Cape Horn for service during the Mexican War, he translated Henri Jomini’s Vie Politique Et Militaire Art De Napoléon (Political Life and Military Art of Napoleon).

Halleck served as both an engineer and military administrator in Lower California during the Mexican War. In 1854, Halleck resigned his commission and became one of California’s leading lawyers. Nicknamed ‘Old Brains’ or ‘Old Wooden Head,’ President Lincoln appointed him a major general dating from August 19, 1861. [6]

Union Plans

President Abraham Lincoln ordered that his western armies needed to march against the Confederate positions in Kentucky and Tennessee by February 22,1862. McClellan had wanted a movement against Unionist-leaning eastern Tennessee; however, both Buell and Halleck advised the general-in-chief that the transportation systems in that part of Tennessee were inferior. So, it was agreed that a movement must be made into central Tennessee.

Halleck was aware of Confederate fortification and gunboat construction up the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. Brigadier General Charles Ferguson “C.F.” Smith used ships assigned to him, USS Lexington and USS Conestoga from the Western Gunboat Flotilla, to observe Confederate activities. Smith confirmed that the Confederates were making a serious effort to defend this line of approach into Tennessee. Halleck knew he needed to take the initiative as he had received intelligence that the hero of Fort Sumter and the battle of Bull Run, General P.G.T. Beauregard, was soon to arrive with reinforcements from Virginia. Halleck needed to act immediately, and fortunately, he had several aggressive subordinates to stage a combined operation to open the door to central Tennessee.

Union Field Commanders

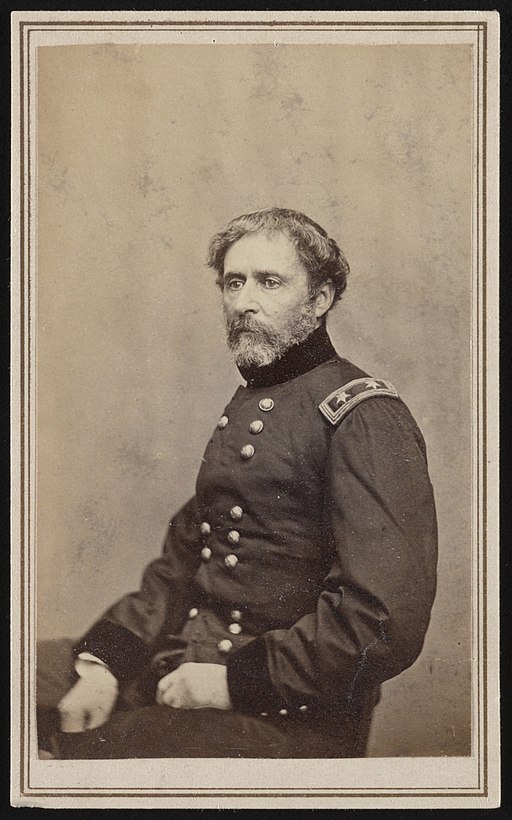

General C.F. Smith was an 1826 West Point graduate and later became both a professor and Commandant of Cadets, USMA, from 1838 to 1843. A hero of the Mexican War, during which time he was brevetted to the rank of colonel, he had also served under Albert Sidney Johnston during the Utah Expedition. Smith was quickly promoted to brigadier general when the war erupted and assigned to the Department of Missouri. [7]

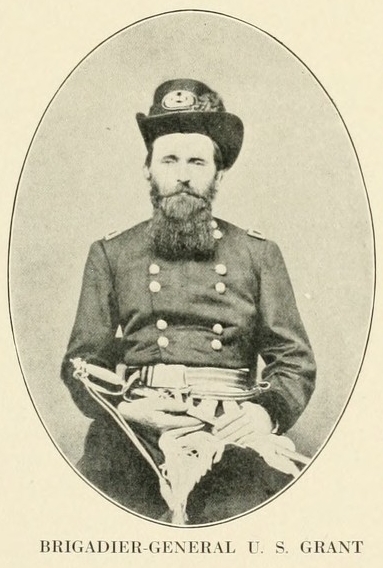

One of Smith’s students at West Point was Ulysses Simpson “U.S.” Grant. Grant graduated in 1843 and proved to be a hero during the Mexican War. While serving in the Pacific Northwest, he had taken to the bottle and was forced to resign his commission in 1854. A failure in civilian life, Grant was named colonel of the 21st Illinois Regiment in June 1861, and soon was named brigadier general. Despite a near disaster during the battle of Belmont, Grant was given command of two divisions. These divisions were commanded by Gen. Smith and by the bombastic political general John A. McClernand. In late January 1862, Grant was ordered to advance against Fort Henry. [8]

Western Gunboat Flotilla

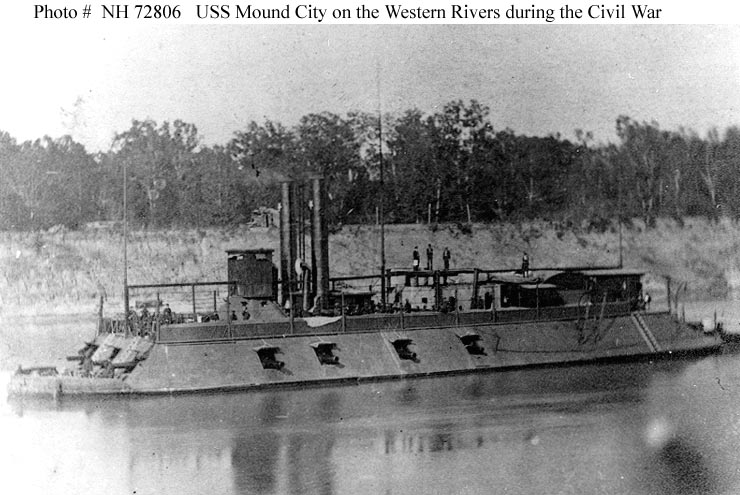

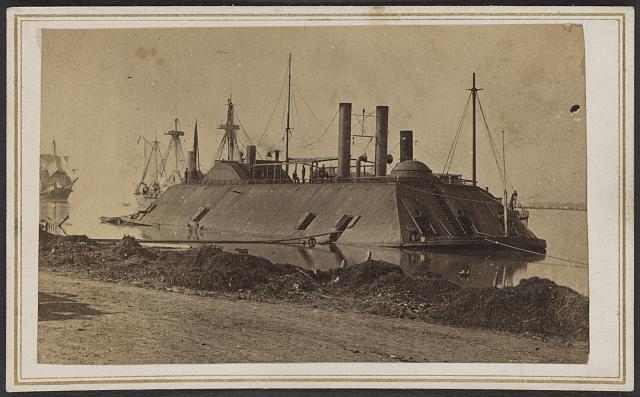

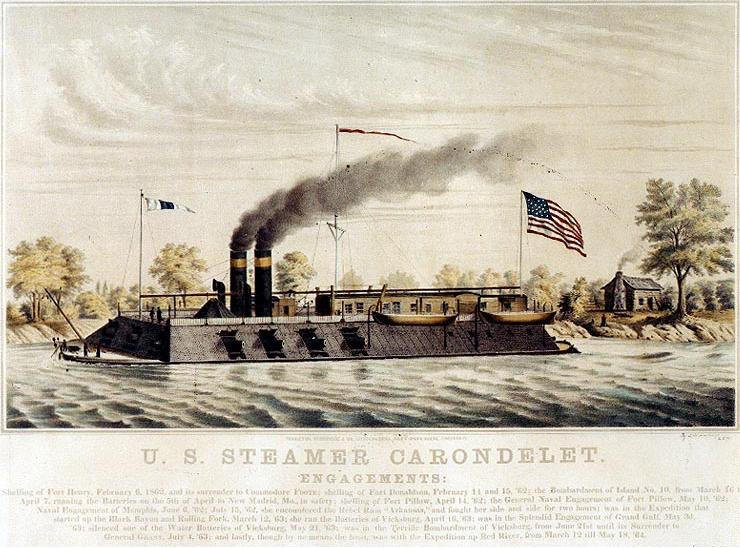

The key to Grant’s successful movement was the Western Gunboat Flotilla. When the war started, the Federals recognized they needed gunboats on the western rivers to advance against Confederate forts and fortified cities. It was critical to Northern commerce to be able to transit the Mississippi River. James Eads, a wealthy St. Louis businessman and shipyard owner, had suggested to Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that a fleet of iron gunboats was needed to control the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Welles was too busy organizing the Southern coastline’s blockade, so Eads’s concept of a ‘brown water navy’ was turned over to the US Army. Welles allowed Commander John Rodgers and Naval Constructor Samuel M. Pook to design and supervise the construction of the casemated City-class ironclads. They were nicknamed ‘Pook’s Turtles’ because of the shape of their casemates. Eads was given the contract to build seven ironclads in his Carondelet, Missouri (near St. Louis), and Mound City, Illinois, shipyards.[9]

City-class Ironclads

These ironclads were laid down mostly in early October 1861. They were 175 feet in length with a beam of 51.2 feet and a draft of 6 feet. The City-class included Cairo, Carondelet, Cincinnati, Louisville, Mound City, Pittsburg, and St. Louis. A center wheel powered these vessels, able to make 5.5 knots. The armor was 2-inch iron plate that was 13 inches wide, and 11 feet long, over a wood backing. These ironclads were not shot-proof; yet, they gave the Union tremendous advantage when they were commissioned in January 1862.

Several of this class of ironclads had different armaments and maintained a mixed battery of 14 guns. Generally, the ships were armed with three VIII-inch shell guns, four 42-pounder rifles, six 31-pounder rifles, and one 12-pounder rifle. The 42-pounder rifles were unreliable and often burst. [10]

Other Ironclads And Timberclads

Commander Rodgers also arranged for two other ironclads to be created from existing vessels. USS Benton was converted from a catamaran snagboat, Submarine No. 7, using a James Eads design. It had a rectangular casemate of 2.5 inches of iron backed by wood, and its center wheel propulsion system could make 5.5 knots. The Benton had a complement of 176 officers and men. The 202-foot long ship was heavily armed with two IX-inch shell guns, seven 42-pounder rifles, and eight 32-pounders.

The USS Essex, designed by Captain William D. Porter (nicknamed ‘Black Bill’ for his dark complexion), was David Dixon Porter’s older brother. The Essex was converted from the merchant river ferry New Era. In its first configuration, the ironclad was 156 feet long, protected by three inches of iron plate, and armed with five IX-inch shell guns. [11]

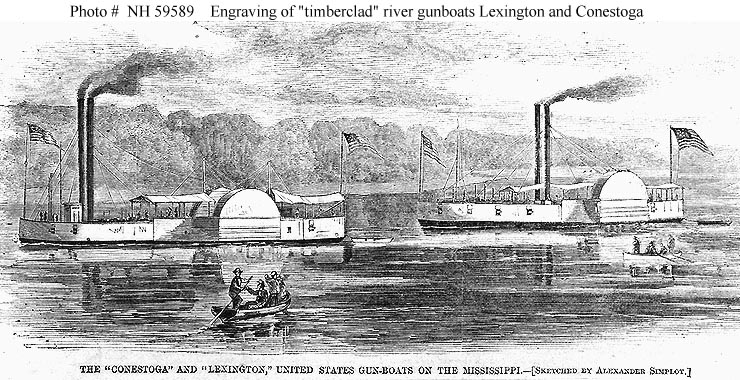

Rodgers also organized the purchase of three ‘timberclads.’ USS Lexington was converted from a sidewheeler towboat. It was 177.6 feet in length and armed with two 32-pounders and four VIII-inch shell guns. The two other timberclads, Conestoga and Tyler, were similar to USS Lexington.[12]

Naval Command

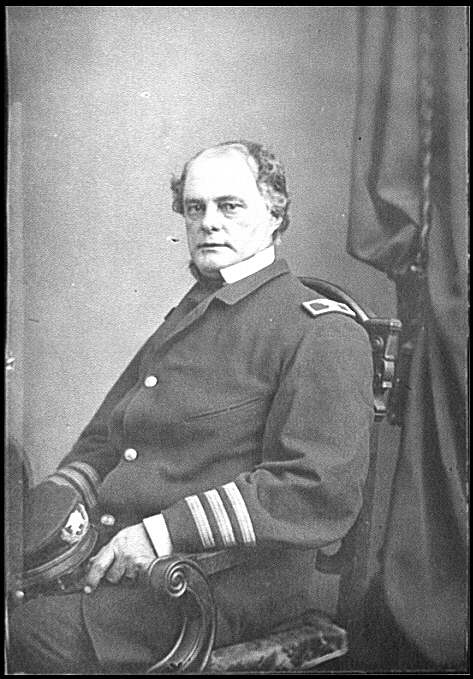

The original commander of the Western Gunboat Flotilla was John Rodgers; however, he feuded with Major General John C. Fremont and was replaced by Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote. After attending West Point for a few months, Foote joined the US Navy as a midshipman in 1822.

He was deeply religious and held strong views against slavery and the slave trade. Foote also created the Naval Temperance Society and was considered a model naval officer. He served with distinction in every position he held. [13]

Down The Tennessee

Grant and Foote developed a viable combined operation that was focused on the capture of Fort Henry. The Union army commander intended to bring his 15,000-man force down the Tennessee by transport. He meant for C.F. Smith to capture Fort Heiman on the river’s west bank. He then wanted to land McClernand’s division near Panther Creek, out of range of Fort Henry’s guns. Once his troops were in place, Foote would bombard the fort as the infantry could invest the defense.

On February 4,1862, Grant went aboard Commander Porter’s USS Essex to review the landing site and test Fort Henry’s guns. Essex approached the fort and was struck by a rifled shot from the fort. Grant later wrote, “One shot passed very near where Captain Porter and I were standing; struck the deck near the stern, penetrated and passed through the cabin and so out into the river.” The Essex then fell back upstream as Grant needed to return to Paducah, Kentucky, to transport the rest of his army to Fort Henry. [14]

Problems At Fort Henry

Marylander Brigadier General Lloyd Tighman commanded Fort Henry. Tighman graduated from West Point in 1836. He resigned from the US Army shortly after matriculation to work as a railroad construction engineer. During the Mexican War, Tighman served on the staff of Major General David Twiggs and later was a captain of a battalion of volunteers from Maryland and the District of Columbia. A resident of Paducah, Kentucky, Tighman joined the Confederate army in 1861 and was quickly promoted to brigadier general. [15]

Tighman was eventually assigned to command Fort Henry, and immediately upon his arrival there, he recognized the fort’s low lying position. Located in the Tennessee River’s floodplain, heavy rains flooded the defense; and high waters inundated the magazine and overflowed many of the gun positions. Only nine cannons, with limited ammunition, could be serviced. Tighman knew most of his troops were poorly armed with flintlock muskets, many dating back to the War of 1812. The general abandoned Fort Heiman on February 4, ordering Col. Heiman to march 3,400 men twelve miles over rain-soaked roads to Fort Donelson. Tighman decided to remain at Fort Henry with about one hundred men to cover the rest of his command’s retreat. [16]

Naval Assault

Meanwhile, heavy rains delayed Grant’s divisions in reaching Fort Henry to facilitate their attack on February 6. Even though Grant’s command was not ready for the assault, the naval attack began at 12:30 p.m. Foote sent his ironclads, Essex, Carondelet, Cincinnati, and St. Louis in a line abreast and opened fire on Fort Henry at a range of 1,700 yards. These ships were followed by the timberclads Lexington, Conestoga, and Tyler.

As the ironclads closed about 600 yards from the fort, “The fire from both gunboats and fort increased in rapidity and accuracy,” Flag Officer Foote recalled. All the ironclads were struck by shot; however, only ESSEX was severely damaged. Foote noted in his report: “ESSEX, unfortunately, received a shot in her boilers, which resulted in the wounding, by scalding, of 29 officers and men, including Commander Porter….The ESSEX then necessarily dropped out of the line, astern, entirely disabled.” [17]

Despite the damage to Essex, Tighman was unable to hold the fort for more than one hour and fifteen minutes. With several of his guns out of action and low on ammunition, he hauled down the Confederate flag and surrendered. The Confederate casualties were five killed, 11 wounded, and 94 captured. The Federal losses were 11 killed, five missing, and 31 wounded. [18] Such losses were minimal in comparison to the opening of the Tennessee River into Alabama. It was a much needed Union victory.

Lieutenant Henry A. Wise of the Bureau of Ordnance and Hydrography, wrote Foote: “We all went wild over success, not unmixed with envy, when news came of the reduction of Fort Henry. Uncle Abe was joyful…[19] The Army also claimed its share of the Fort Henry victory as Henry Halleck telegraphed Washington, DC: “Fort Henry is ours. The flag is reestablished on the soil of Tennessee. It will never be removed.”[20]

Timberclad Raid

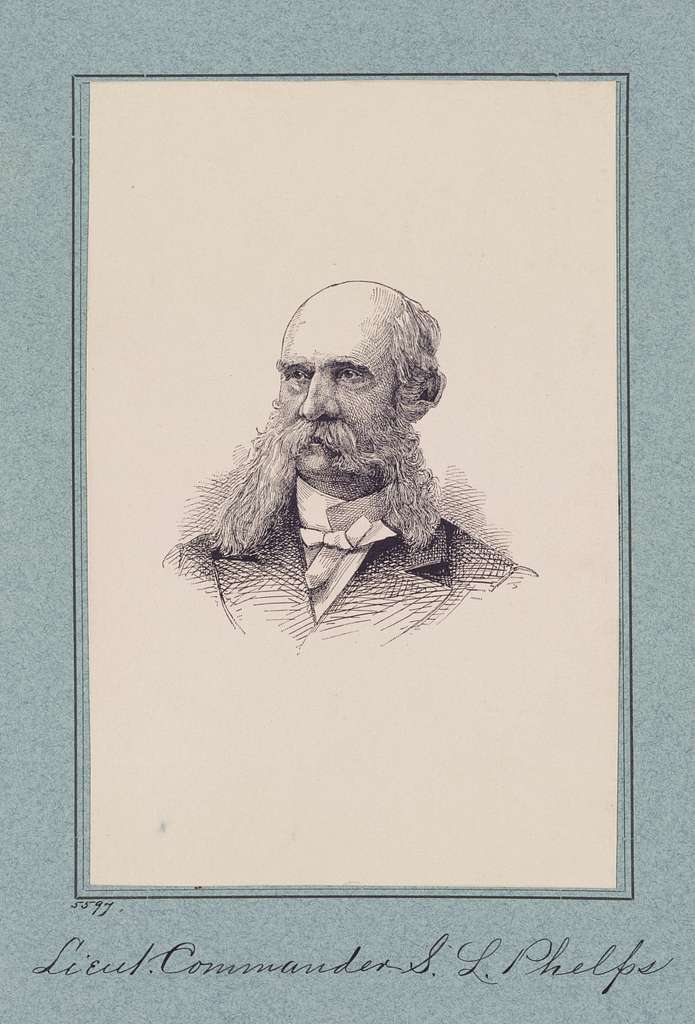

In the battle’s aftermath, Foote sent Lieutenant Commanding Seth Ledyard Phelps to ascend the Tennessee River. Phelps had joined the US Navy as a midshipman in 1841. He served in gunboats during Vera Cruz’s siege and in several squadrons, including the African Squadron on slave trade patrol before the war. He had already been active with the Western Gunboat Squadron, scouting the Ohio, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers using timberclads before the campaign was initiated.

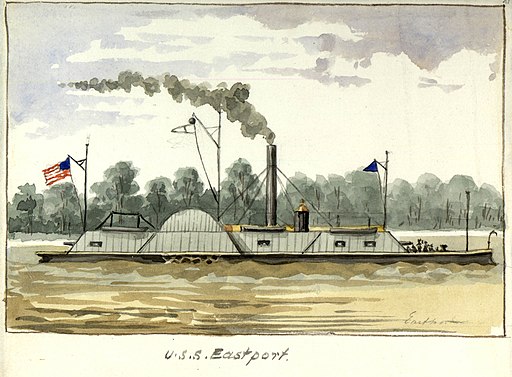

Phelps’s raid was successful and reached down the Tennessee River to Muscle Shoals, Alabama. He destroyed the Memphis & Charleston Railroad bridge and several steamers. Most importantly, Phelps captured the ironclad ram Eastport, under construction at Cerro Gordo, Tennessee, on February 7, 1862. [21]

The Eastport was under conversion from the sidewheeler C.E. Hallman. The ram was 280 feet in length, with a 43-foot beam and a 6 ½ foot draft. The vessel was plated with two inches of iron plate but was not armed. The Eastport was then towed to Mound City, Illinois, for completion. [22] The raid conducted by Phelps was considered “a perfect success. It discovered the real weakness of the Confederacy in that direction, the feasibility of marching an army into the heart of the Confederacy.” [23] Phelps then rejoined Foote’s squadron in Cairo, Illinois.

Confederates Prepare Fort Donelson

The loss of Fort Henry was devastating to the Confederacy. Albert Sidney Johnston realized on February 7 that he would have to abandon both Bowling Green and Columbus, Kentucky. Johnston had minimal manpower with 12,000 men at Columbus, 22,000 troops at Bowling Green, and 5,000 men at Fort Donelson. Since the Confederates had to make a stand in middle Tennessee to defend the vital manufacturing center of Nashville, P.G.T. Beauregard, newly assigned to Johnston’s army, advised Johnston that he must send reinforcements to Fort Donelson. Johnston wanted Beauregard to take command there; however, Beauregard fell ill with a throat ailment. Instead, Brigadier General John B. Floyd was given the post; and this proved to be a significant mistake.

Inept Leadership Plagues Fort Donelson

John Buchanan Floyd was the son of a governor of Virginia, Dr. John Floyd, and graduated from South Carolina College in 1829. The younger Floyd worked as a lawyer; however, he lost a fortune cotton speculating in Arkansas. He later served as governor of Virginia from 1848 to 1852 and was named by President James Buchanan as Secretary of War in 1857. Floyd was involved in numerous financial improprieties like the Indian Trust Bond Scandal and was accused of shipping, muskets, cannons, and military goods South when secession threatened the nation. He resigned his position and soon was named brigadier general in the Confederate service. After an abysmal performance in West Virginia, he was sent to serve under A.S. Johnston. His division was sent to Fort Donelson to coordinate its defense.[24]

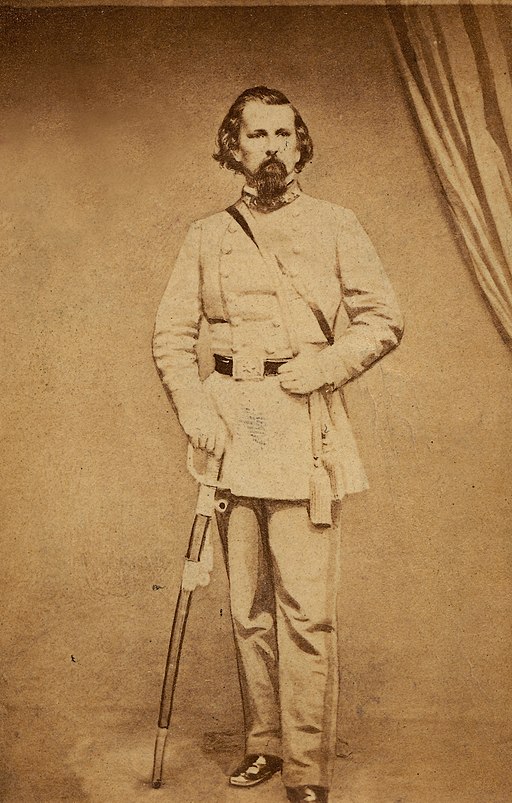

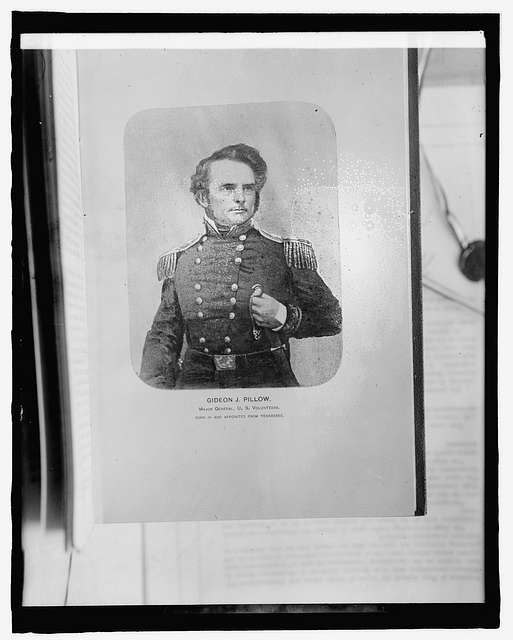

Floyd’s command was called the Army of Central Kentucky with three brigades containing 17,000 soldiers. He commanded one of the brigades. The other two were led by brigadier generals Gideon J. Pillow and Simon Bolivar Buckner. Pillow, born in 1806, was an 1827 graduate of the University of Nashville. He was President James Polk’s law partner and consequently, received an appointment as brigadier general of volunteers during General Winfield Scott’s march on Mexico City. He argued with Scott repeatedly and, according to many observers, ordered his men to build earthworks facing the wrong direction. Pillow was named brigadier general in the Confederate army in July 1861. He had been in command at Columbus, Kentucky, and fought an inconclusive engagement with Grant during the November 7, 1861, battle of Belmont, Missouri. {25]

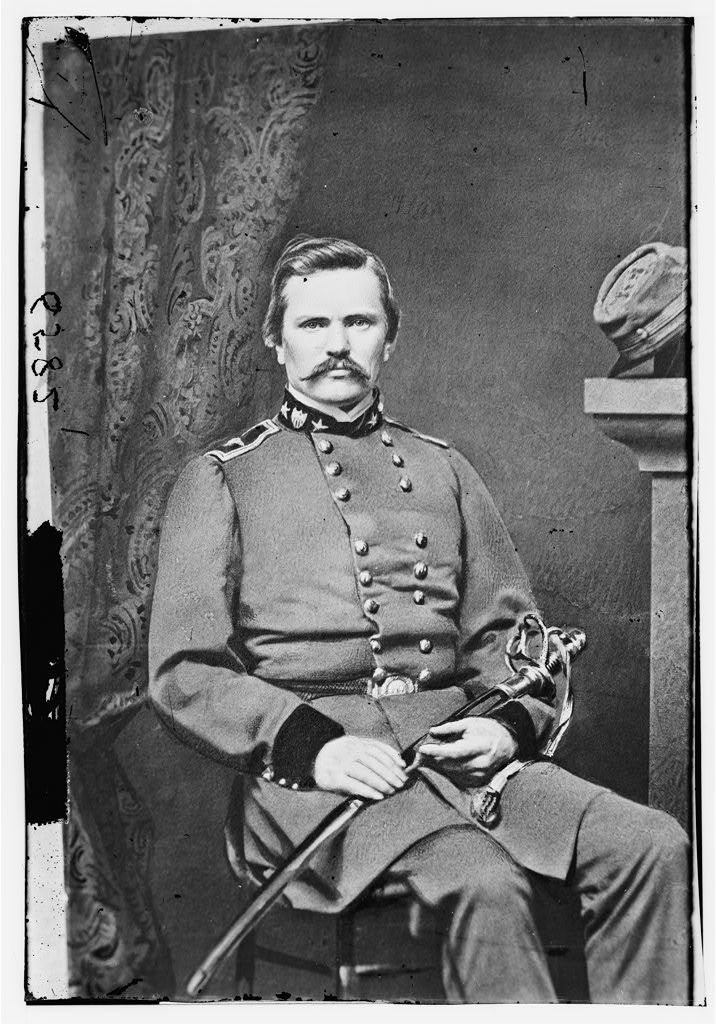

Simon Bolivar Buckner was the other brigade commander. An 1844 graduate of West Point, he earned two brevets during the Mexican War. He resigned from the US Army in 1855 to engage in business. When the war started, Buckner was the adjutant general of Kentucky’s state guard, and he worked to maintain that state’s neutrality. As this proved to be an impossible task, he joined the Confederacy as a brigadier general. [26]

Union Moves Against Fort Donelson

Grant advised his supervisor, Gen. Halleck, that he planned to capture Fort Donelson with naval support. Halleck was apprehensive about this movement; however, the army/navy success on the Tennessee River convinced him to approve this combined campaign.

Grant had conducted a reconnaissance of Fort Donelson on February 7 and came within one mile of the fort’s outerworks. The Union general had nothing but contempt for the leading Confederate commanders at Donelson. While Buckner was Grant’s friend from West Point and the Mexican War (he had loaned money to Grant to go home after his resignation), the others were just political creatures. Grant noted, “I had known General Pillow in Mexico, and judged that with any force, no matter how small, I could march up within a gunshot of any intrenchments he was told to hold…I knew that Floyd was in command but he was no soldier, and I judged that he would yield to Pillow’s pretensions.”

Grant believed that Floyd did not have the elements of being a soldier and was “further unfitted for command, for the reason that his conscience must have troubled him and made him afraid. As Secretary of War, he had taken a solemn oath to maintain the Constitution of the United States and to uphold the same against its enemies. He betrayed that trust.” [27]

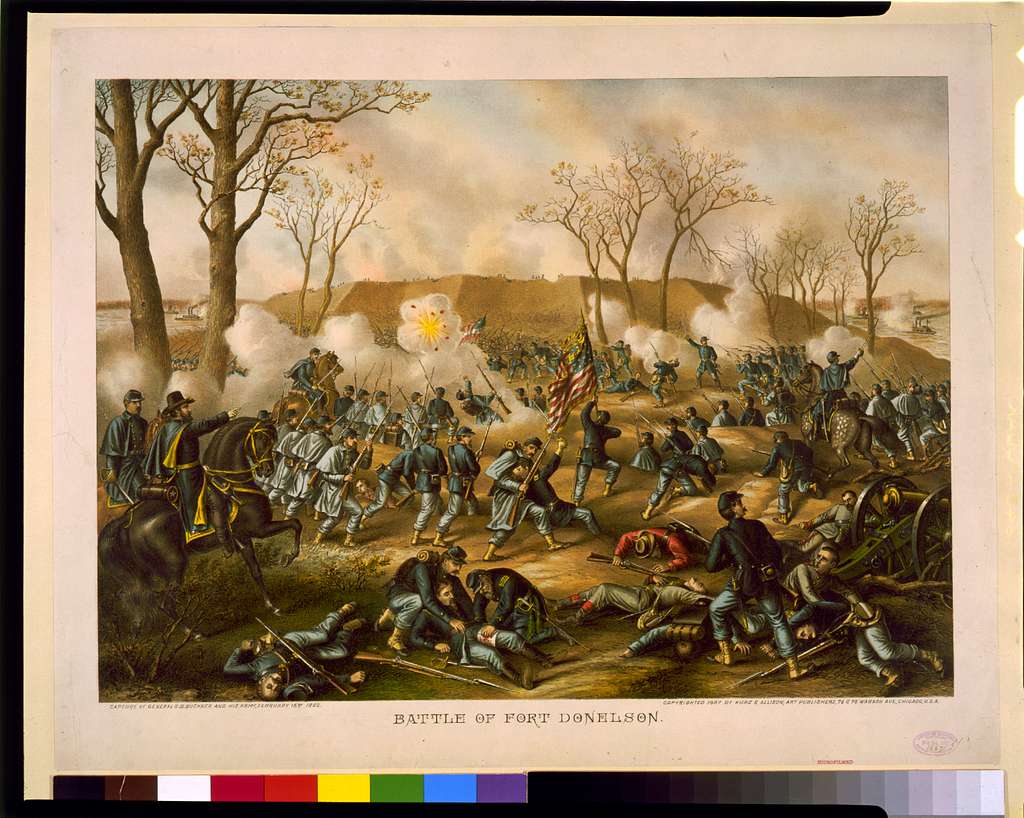

Investment Of Fort Donelson

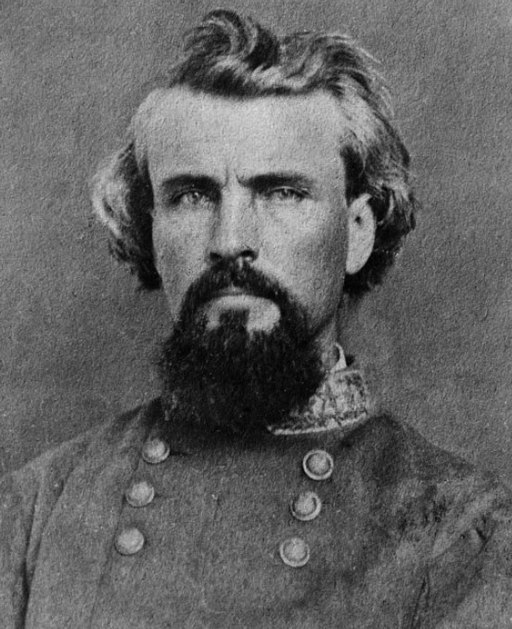

Grant moved most of his men from Fort Henry to Fort Donelson over two bad roads on February 7. Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry delayed the Union advance; nevertheless, the Unionists began to form their encirclement that evening and early the next day. C.F. Smith’s division was on the Union’s left, Colonel W.H.F Wallace’s brigade in the center, and McClernand’s command on the right. The terrain made it difficult for the Union right to reach the Cumberland River to close all avenues of Confederate escape. {29}

Carondelet Diversions

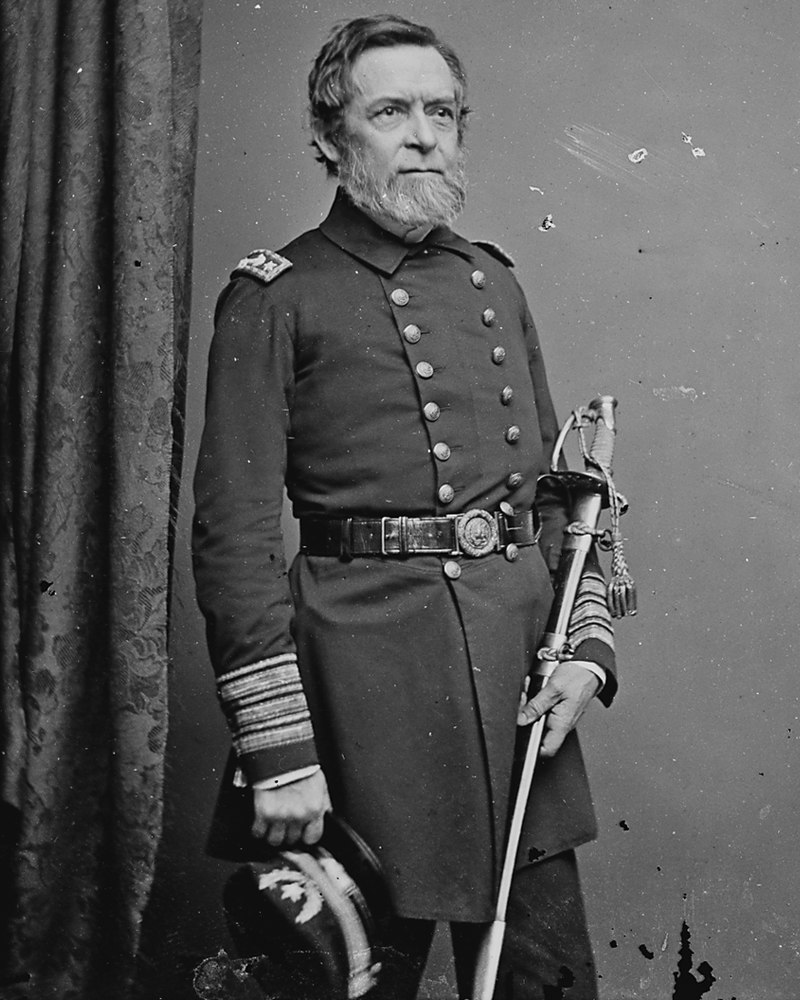

Grant asked Commander Henry Walke to bring his ironclad down the Cumberland River to test Donelson’s river defenses and cover his troop displacements. From Princess Anne County, Virginia, Walke joined the US Navy as a midshipman in 1827 and had a successful career. When Florida left the Union, Walke organized the removal of Federal personnel from Warrington Navy Yard, Pensacola, Florida, as the Confederates forced the yard’s surrender.

Assigned to the Western Gunboat Flotilla, Walke was eventually named commander of USS Carondelet and captained it during Fort Henry’s battle. The ironclad was towed by the hired steamer Alps to Paducah to re-supply and head down the Cumberland River. Walke arrived at Grant’s request near Fort Donelson and engaged the fort’s water batteries to divert the Confederate attention as Union troops took their positions.

The Carondelet was hit several times by Confederate shot. The Union was hit twice by Confederate shot, “one of which was a 128 pounds solid shot,” according to Commander Walke. “It passed through our port casemate forward, glancing over our barricade at the boilers, and again over the steam drum, it struck our steam heater, fell into the engine room without striking any person, although splinters wounded slightly half dozen of the crew.” Commanders of the City-class ironclads, after they had witnessed the damage sustained by the Essex during the Fort Henry attack, placed bags filled with coal to act as a barricade protecting each ship’s boiler. The Carondelet returned to its duel with the shore batteries until darkness fell. [30]

More Naval Support And Unit Reinforcements

Late on February 13, Andrew Foote’s flotilla arrived near Fort Donelson to join with Carondelet. Foote brought with him the ironclads St. Louis (flagship), Louisville, and Pittsburg along with the timberclads Tyler and Conestoga. Foote’s fleet brought transports carrying Colonel John Milton Thayer’s brigade. Thayer, after graduating from Brown University, moved to Nebraska. There he became a famous Indian fighter. When the Civil War broke out, he became commander of the 1st Nebraska Regiment and later became a brigade commander.

Thayer was assigned to Brigadier General Lew Wallace’s division which had just arrived from Fort Henry. Wallace, later famous as the author of Ben Hur: A Tale Of The Christ, served as 1st lieutenant of the 1st Indiana Regiment during the Mexican War. He was named colonel of the 11th Indiana in 1861 until promoted to brigadier in September of that year. [31] Grant now had 25,000 men facing the 17,000 defenders of Fort Donelson.

Ironclad Attack

At 3 p.m. on February 14, Foote decided to attack the Confederate water batteries. The ironclads moved to within 400 yards of the fort, and for one hour and a half, the Union ships met with heavy and accurate fire from the batteries. Foote reported that his flagship, St. Louis, “alone received 59 shots, 4 between wind and water, 1 in the pilot house mortally wounding the pilot, and other places.” [32] Even Flag Officer Foote was wounded in the foot. Without its wheelhouse, St. Louis drifted down the river.

All of the ironclads suffered grievously during the attack. Of the estimated 500 Confederate shots, they scored many hits, and their impact on the ironclads was devastating. The tiller ropes of Louisville were shot away, forcing the gunboat to drift away from the batteries. The Pittsburg, according to its commander Egbert Thompson, received “at least 30 shots. The principle disasters are the two shot holes on the bow….next in importance, perhaps, was a 128 pound round shot through the pilot house….Another shot entered the middle port, and passed out at the stern, through the cabin, first cutting its way through a stack of hammocks and coal bags, escape pipe, wheelhouse, etc., not touching a man.”

Pittsburg’s pumps could not keep up against the flow of water. The ironclad then moved downriver and laid against the riverbank to plug the holes between wind and water. The Carondelet also suffered severe damage as it was hit by 35 shots causing several leaks. A 42-pounder rifle burst during the engagement, and a VIII-inch shell hit the ironclad from one of the timberclads which penetrated the casement with fragments. The casualties amounted to 10 killed and 43 wounded. [33] The naval attack was a complete failure.

Confederates Strike Out

Floyd had called a council of war on the evening of February 14 to determine the course of action the garrison should take. Buckner had previously suggested that part of the division escape the fort to break up Union communications and march to Nashville on February.11. Pillow had overruled this with Floyd’s support. After the Union fleet’s successful repulse, they decided that the noose was tightening and that an escape should be made. If they attacked the Union left, the Confederates could reach Wynn’s Ferry and Forge roads and then march to Nashville.

Pillow began the attack at dawn and pushed through McClernand’s command. The Federals soon became demoralized, feeling overwhelmed by the Confederate flank attack. McClernand’s men were running out of ammunition as Pillow reached toward the roads to Nashville. As Buckner had not moved quickly enough, Pillow had a confrontation with him. Buckner got his troops to join the attack, and it appeared by 9:30 a.m. that the Confederates had almost achieved their goals.

Colonel Forrest flanked the new Union position and urged Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson to launch an all-out attack. Instead, he merely slowly pressed his troops forward. Had Johnson pressed the attack, Forrest believed the attack would have completed the Union route. By now, the Confederates had opened the way to Nashville and had pushed the Federals back more than two miles. At 12:30 p.m., Pillow thought his men needed to regroup, so he ordered them to end their advance and return to Fort Donelson. [34]

Federal Response

Grant now realized it was time to counter-attack. Even though the Union right was utterly demoralized, Grant was determined to make an immediate strike against the Confederate outerworks by Smith’s division. Grant knew that most of Floyd’s command had participated in the morning’s attack and that the Confederates would have few troops to maintain their earthworks and wished to deal a heavy blow against the fort. As Smith organized his assault, Grant rode along the right of the Union line encouraging McClernand’s troops: “Fill your cartridge boxes, quick, and get into line; the enemy is striving to escape and must not be permitted to do so.” [35]

Smith personally led his men forward, and soon they had captured the outworks. They threatened to break into the fort itself. Meanwhile, Lew Wallace used troops from his and

McClernand’s divisions and forced the Confederates back into their original positions by nightfall. Grant was ready to resume his attack in the morning which he knew would enable him to capture the fort. [36]

Confederate Final Conference

Floyd held another council of war on the evening of February 15. Both he and Pillow thought the Confederates had achieved a victory and could finish their escape in the morning. Simon Bolivar Buckner disabused that opinion, explaining that the fort would quickly fall when the Union attacked. Floyd thought if captured, he would be charged with treason or corruption, so he fled the scene on a steamer with two Virginia regiments. Pillow also feared reprisals, and he left the fort in a small boat while Forrest escaped the defense with his command along the Forge Road. [37]

‘Unconditional Surrender’ Grant

The next morning, February 16, 1862, Buckner sent a message to Grant asking for an armistice and surrender terms. Grant replied with a terse statement: “Yours of this date, proposing armistice and appointment of Commissioners to settle terms of surrender, is just received. No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.” Buckner had no choice but to accept Grant’s terms. [38]

Impact

The Grant and Foote team had proven the power of combined operations in the Western Theater. This playbook would be repeated often by subsequent commanders enabling the Mississippi’s opening by July 1863. The Confederate defeats were significant as A.S. Johnston had to abandon Nashville. His army had surrendered 12,000 men, which the Confederacy would find hard to replace. Johnston would have to strip other commands, such as New Orleans, to enable his attempt to stem Union advantages. Once the Confederates abandoned Nashville, it forced them to leave Kentucky and much of Tennessee. It was a defeat never to be recovered by the Confederacy.

Throughout the North, church bells rang as this was the first major Federal land victory since the war erupted. Newspapers blared the exploits of new heroes that were fighting to preserve the Union. Ironclads were an expression of the North’s inventiveness and industry, surely designed to free the Mississippi River Valley from Confederate control to reopen Midwestern commerce. Most of all, ‘Unconditional Surrender’ Grant had emerged as a commander who would take action directly at the enemy and achieve victory. The Fort Henry/ Fort Donelson campaign brought Grant into the forefront as he began his work to reunite the fractured nation.

ENDNOTES

1 Kendall D. Gott, Where The South Lost The War: An Analysis Of The Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862, Mechanicsville. PA: Stackpole Books, 2003, p.73.

2 Ezra J. Warner, Generals In Gray, Norwalk, Ct.: The Easton Press, 1987, p.75.

3 J.E. Kaufman & H.W. Kaufman, Fortress America, Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2007, p.241; and Robert B. Roberts, Encyclopedia Of Historic Forts, New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1989, p 749.

- Kaufman & Kaufman,p. 243; and Roberts, pp 739-740.

- Ezra J. Warner, Generals In Blue, Norwalk, CT: The Easton Press, 1987, p. 51.

- IBID, pp.195-196.

- IBID, p 455.

- IBID, p 293, pp 183-184

- Angus Konstam, Union River Ironclads 1861-65, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002, pp.5-8.

- Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies 1855-1883, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001, p.114.

- IBID, p 116.

- IBID, pp 118-119.

- Patricia L. Faust, ed., Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Civil War, New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1986, pp.265-266.

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs Of U. S, Grant, New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885, Vol. I, p. 290.

15.Ezra J. Warner, Generals In Gray, Norwalk, CT: The Easton Press, 1987, p. 306.

- Gott, pp. 91-22.

17.Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Navies In The War Of The Rebellion (Hereinafter noted as ORN), Ser. I, vol. 22, p. 538.

18 Faust, p 274.

19 ORN, Ser. 1, vol. 22, p. 549.

20 Gott, p 105.

21 Jay Slagle, Ironclad Captain: Seth Ledyard Phelps & The U.S. Navy, 1841-1864. Kent State University Press, 1996, p 163.

- Silverstone, p. 117.

23 Benson Lossing. The Pictorial History Of The Civil War In The United States Of America, Hartford: Thomas Belknap Publisher, 1880, p. 249.

24 Warner, Generals In Gray, p. 89-90.

25 IBID, p. 241.

26 IBID, pp. 38-39.

27 Grant, p. 294.

28 IBID.

29 ORN, Ser. I, vol. 22, pp. 587-588.

30 IBID.

31 Warner, Generals In Blue, pp 499 and 536.

32 ORN, Ser. I, Vol. 22, pp 586-587.

33 IBID. pp 586-587, pp 591-93.

34 ORN, Ser. 1, vol. 22, p. 604; and Gott, pp 219-221.

35 Grant, 307-308.

36 Grant 308; and Gott, pp 231-35.

37 ORN, Ser. I, vol. 22, pp. 605 -608; and Gott, pp 240-41, pp 252-57.

38 Grant, pp 310-312.