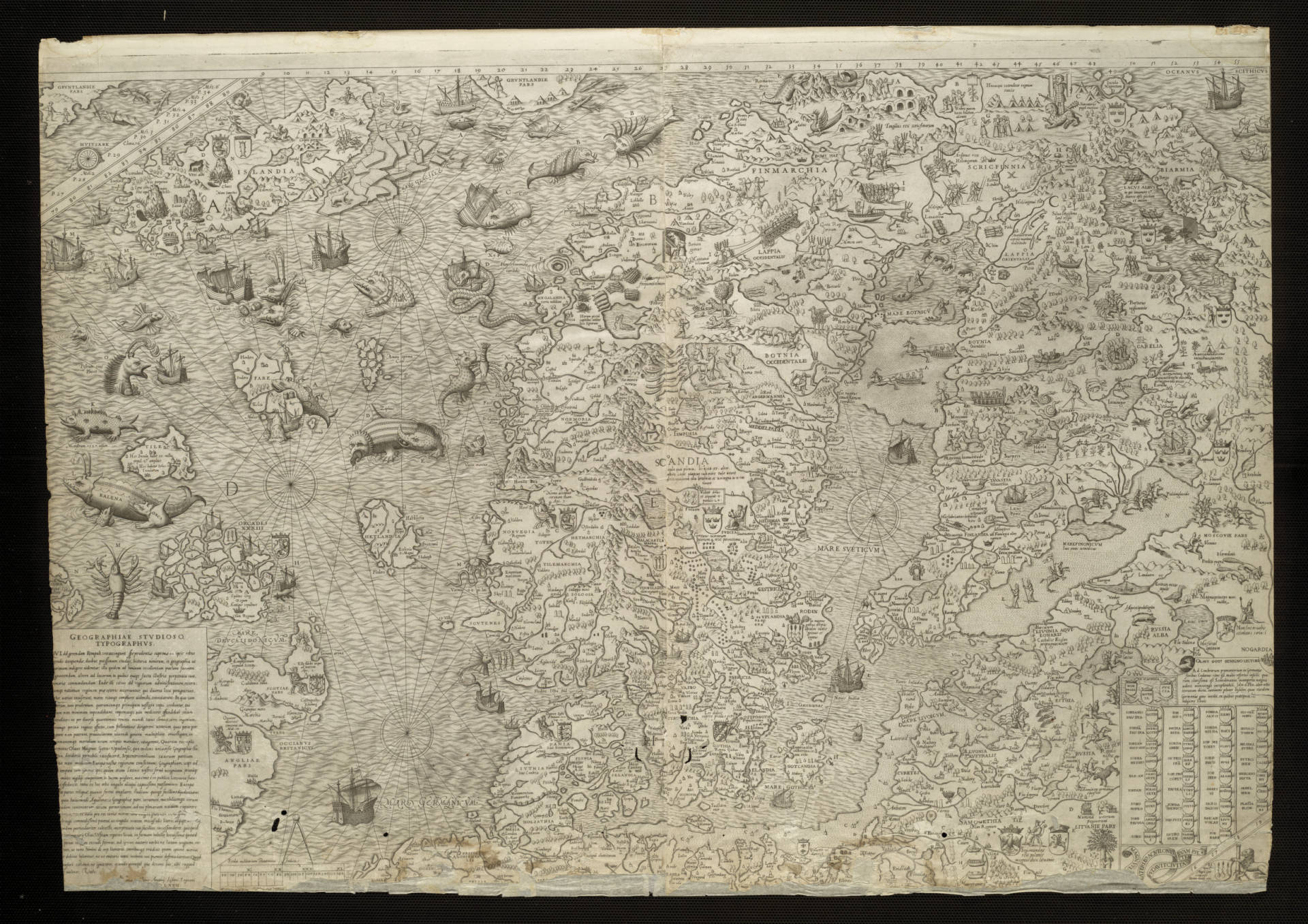

As noted in a previous blog, one of the most famous and intriguing maps of the 16th Century is Olaus Magnus’ Carta Marina, first published in 1539. The Carta Marina depicts the geography of Northern Europe, the British Isles and Iceland. More importantly, it is populated with figures from Scandinavian history and folklore, and with animals both real and imagined.

In 1555 Magnus published his Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (History of the Northern Peoples), which included a black and white version of the Carta Marina. The library has a 1561 Italian edition of the work, Storia d’Olao Magno, arcivescovo d’Vspali, de’ costvmi de’ popoli settentrionali, as well as a 1567 Latin edition. The 1567 edition in the library contains a simplified version of the Carta Marina. The 1572 version depicted below is from the University of Minnesota Libraries, James Ford Bell Library. It will have to stand in for the example in the Museum’s library due to the condition of the map and the difficulty of photographing it.

A full color version of the Carta Marina was published on nine sheets. The reproduction image below is also from the holdings of the University of Minnesota Libraries, James Ford Bell Library. It shows Sheet 2, depicting the seacoast of northwestern Scandinavia, with Greenland in the upper left corner. Additionally, it depicts a wide range of sea monsters, many of which would show up in later maps.

Sheet two of the Carta Marina is rich in details. One of the more intriguing monsters on this sheet is the the large sea serpent in the lower left corner, which is seen destroying a sailing ship. Just above it, labelled with the Letter “C”, is a large whale attacking a ship. These types of interactions between men and creatures of the sea are common in the Carta Marina.

Other sea monsters of interest are the two creatures in the top center of the sheet. They are described as “Two colossal sea monsters, one with dreadful teeth, the other with horrible horns and burning gaze – the circumference of each eye is 16 to 20 feet.”[i]

Abraham Ortelius and the Theatre of the World

As I have written previously, most scholars consider Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum orbis terrarium (Theatre of the World) as the first modern atlas. Between 1570 and 1612, thirty-one editions of the Theatrum orbis terrarium were printed. Many of the later editions of the atlas incorporated up-to-date cartographical information on the known world. They also included numerous illustrations of sea monsters. It is not somewhat curious that the first modern atlas would include illustrations of sea monsters and other mythical beasts?

Islandia (Iceland)

The map of Iceland shown below was first included in the 1590 edition of the Theatre of the World. This image is from the library’s 1592 edition. According to a website published by the National and University Library of the Iceland which shows digitized copies of all old maps of Iceland, “Although the map is faulty in many ways, it is far superior to all earlier maps of Iceland in content and execution. Here for the first time we find a map giving a more or less complete survey of all settlements in the country and most places of interest.”[ii]

In spite of the accuracy of the map, it is the seas surrounding Iceland that provoke a response from modern viewers. They are full of fantastical creatures, a few of which I’ll highlight below. While the sea monsters from Olaus Magnus certainly informed many of the illustrations in the Theatre of the World, many of the creatures depicted had evolved from Magnus’ drawings. One interesting feature of this map is that it included a key to the creatures, all of which are described on the back of the map.

Comparing the Ortelius map with the Carta Marina, I was struck by the fact the monsters in the Carta Marina are frequently seen attacking ships or interacting with men, whereas in the Ortelius map, they are depicted more as specimens. Any idea on why that is the case?

A) The Nahval

In the ocean north of Iceland is a monster described in the Ortelius atlas as “a fish, commonly called NAHVAL. If anyone eats of this fish, he will die immediately. It has a tooth in the front part of its head standing out seven cubites. Divers have sold it as the Unicorn’s horn. It is thought to be a good antidote and powerful medicine against poison. This monster is forty ells in length.”[iii] You may recognize this “monster” as the narwhal.

A cubit is an ancient measurement that is approximately 18 inches. Thus the nahval’s “tooth” is approximately 10.5 feet long. An ell is a former English unit of measure that is equal to 45 inches. According to Ortelius, the nahval is 150 feet long.

D) The Hyena

The hyena is seen in the left center of the map, off the west coast of Iceland. The text describing the hyena reads as follows: “The Hyena or sea hog is a monstrous kind of fish about which you may read in 21st book of Olaus Magnus.”

Magnus has quite a bit to say about the Hyena, which he labels a “sea pig.” He writes, “It has a pig’s head with a crescent moon at the back, four dragon’s feet, a pair of eyes in its loins at each side, and a third on its belly […] at the end a bifurcated tail of a normal fish.”[iv] He goes on to state that “Certainly this sea-pig knows all about the art of plundering with atrocious savagery; and it becomes even fiercer when, with the seal as a friend and accomplice, it molests all kinds of prey.”[v]

There is no no known counterpart to the sea hyena in the world. It is clearly an imagined monster.

G) The Hroshualur

“HROSHUALUR, that is to say as much as Sea horse, with manes hanging down from its neck like a horse. It often causes great hurt and scare to fishermen.” Interestingly, the Hroshualur depicted on the map was not derived from the Carta Marina. It stems from much older origins, namely the Sea Horse, or Hippocampus, from Greek mythology. Renaissance artists frequently used the hippocampus in their illustrations. The hippocampus is associated with Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea, and later with Neptune, the corresponding Roman god.

H) The largest kind of whale

Unnamed in the Ortelius map, this whale is described as “the largest kind of whale, which seldom shows itself. It is more like a small island than like a fish. It cannot follow or chase smaller fish because of its huge size and the weight of its body, yet it preys on many, which it catches by natural cunning, which it applies to get its food.”

I) The Skautuhvalur

“This fish is fully covered with bristles or bones. It is somewhat like a shark or skite, but infinitely bigger. When it appears, it is like an island, and with its fins it overturns ships.” Various sources refer to this beast as a giant ray.

L) Steipereidur

“Steipereidur, a most gentle kind of whale, which for the defense of fishermen fights against other kinds of whales. It is forbidden by proclamation that any man should kill or hurt this kind of whale. It has a length of at least 100 cubits.” A whale 100 cubits in length would be about 150 feet long.

Final thoughts

The beauty and imagery of the sea monsters on Ortelius’s map of Iceland is not to be denied. That he used images from the Carta Marina is clear, even though not all of the monsters depicted are directly from the earlier source. Returning to my earlier question, about why one of the first modern maps of Iceland would have such a rich collection of sea creatures as illustrations, I’m afraid I do not have the answer. Could it be, as Chet van Duzer writes, that the presence of so many fierce sea monsters suggests “that the island was a wild and inapproachable place at the very edge of the known world”?[vi]

Endnotes

[i] Nigg, Joseph. Sea Monsters: A Voyage around the World’s Most Beguiling Map. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 2013, p. 12.

[ii] Islandia, from https://islandskort.is/en/map/show/2, accessed March 23, 2021.

[iii] Nigg, p. 17. The English translations of the key from the Islandia map are from this work.

[iv] Foote, Peter (ed.), Olaus Magnus, Description of the Northern Peoples, London: Hakluyt Society, 1998. Vol. 3, page 1110.

[v] ibid.

[vi] Van Duzer, Chet. Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps. London: The British Library, 2013, p. 111.