Drinking and fighting always seem to have some type of connection. On the early morning of March 9, 1862, CSS Virginia prepared to destroy the remaining Union fleet in Hampton Roads. Its success the day before gave the crew confidence that they would secure a complete victory over the wooden federal fleet. Catesby ap Roger Jones, the Confederate ironclad’s acting commander, thought to give the men even greater encouragement. “We began the day with two jiggers of whiskey,” an elated William Cline wrote, “and a hearty breakfast.” [1] The crew was now truly ready for combat!

Grog was first introduced in the 18th century, eventually a mix of rum, gin, or whiskey with water, sugar, and lime or lemon. It was a boost to sailors fighting the doldrums suffered on long sea voyages or to give a surge of instant courage when preparing for battle. Enlisted men could only drink when their grog ration was issued or when they were on liberty. Officers, however, drank without care and were only punished when their intoxication got in the way of performing their duties. USS Monitor’s paymaster William Keeler fought to do away with the grog ration stating that drinking was the “curse of the navy.”[2] It was true: many Civil War sailors and soldiers were all too often plagued by whiskey, whiskey, and more whiskey.

Grog Ration’s Beginnings

Credit for establishing the grog ration is generally given to Vice Admiral Sir Edward Vernon while commanding a fleet in the West Indies. Vernon was nicknamed “Old Grog,” as he wore grogram (also known as grosgrain, a woven pattern of wool and silk) jackets that were less expensive than pure silk. He was known for showing care for his crew.

On August 21, 1740, Admiral Vernon’s order specified that the twice-daily spirits ration would consist of a half-pint (two gills) of rum mixed with one quart of water. Vernon further suggested that the drink be mixed with sugar and limes or lemons for a better taste.[3] The rum was diluted with water in the presence of a Lieutenant of the Watch. The purser would mix the drink in a scuttled butt (open tub) reserved just for this purpose. The grog ration was given at noon and the end of the day. The crew rallied to receive their allocation when they heard the call, “Up Spirits!”

‘Water, Water Everywhere. But Not A Drop To Drink.’

Water storage was a huge problem on long sea voyages. Since it was stored in wooden casks, the water often became putrid or slimy. If stored improperly, it could result in fevers and diarrhea. So grog (rum or gin) covered the taste of the bad water making it more palatable. The addition of lemon and limes in grog, as Vernon suggested, was successful in curing scurvy. No one knew how [Vitamin C was not discovered until the 20th century] it worked; nevertheless, the Royal Navy began issuing citrus in 1795. When mixed with sugar and then added to grog, the limes and lemons made it healthy, tasty, and refreshing.[4]

Grog And The US Navy

Both the Continental and the US navies followed their British counterparts. The Americans used rye whiskey instead of rum or gin. This mixture was much preferred. Although the US Navy limited the grog ration to one gill rather than two, naval personnel still consumed a tremendous amount of spirits, as proven by the deliveries of the store ship USS Southampton during the Mexican War. In August 1847, Lieutenant John Lorimer Worden, executive officer of Southampton, delivered 431 gallons of whiskey to USS Portsmouth (200 officers and men); and 955 gallons of whiskey to USS Congress (480 officers and men). This operation took two days as other provisions and supplies were also being delivered to both warships. The Southampton supplied whiskey to all of the Pacific Squadron serving in the Gulf of California, including 431 additional gallons of whiskey for Congress and significant amounts to the other vessels operating in the effort to conquer Baja, California.[5]

Temperance

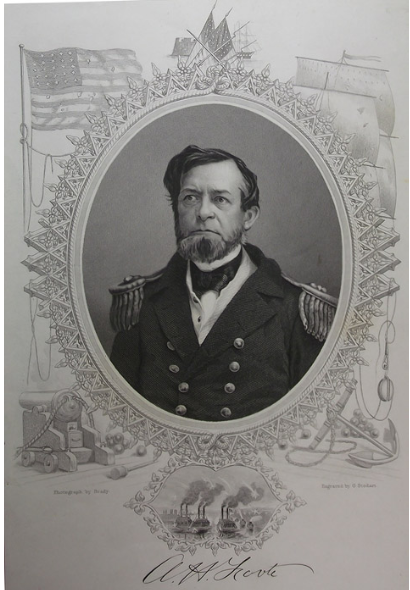

Changing attitudes toward the consumption of spirits was eventually considered a bad practice. Abstaining sailors could opt for a payment of 3 to 5 cents per day if they did not take the offered grog rations. The most notable among those fighting against grog rations was Andrew Hull Foote. The profoundly religious Foote organized the Naval Temperance Society during his 1843-1845 Mediterranean cruise aboard USS Cumberland. This was an important step toward ending spirits on naval ships, which was finally instituted on September 1,1862.

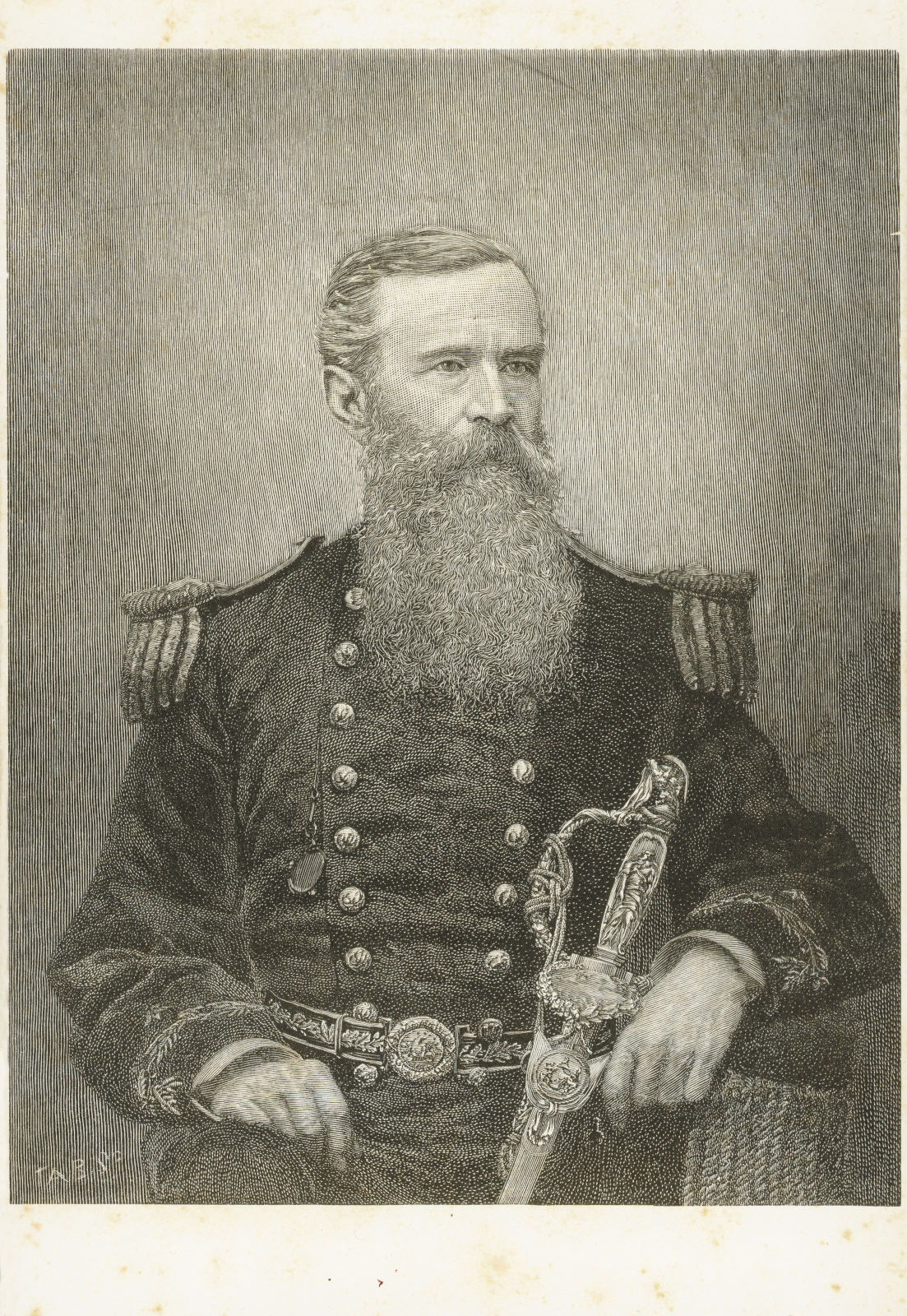

Monitor’s Teetotaler: William Keeler

Acting Assistant Paymaster William Keeler was one of the first officers assigned to the ironclad USS Monitor. The paymaster’s job was critical in maintaining the ship. A clerical position, the duties included managing the ship’s accounts, provisions, supplies, and payroll. A paymaster was expected to exhibit strong writing and mathematical skills. Keeler joined the Navy at age forty as he considered slavery a “hideous deformity” and believed the rebellious Southerners were “traitorous and wretched souls.” He also found the excessive drinking of alcohol a dangerous habit.

During a dinner before Monitor left New York, Keeler realized the wardroom steward, Lawrence Murray, was a drunk. Keeler wrote his wife, Anna, that Murray “had been testing the brandy & champaine [sic] before putting it on the table.” He continued, noting that the dinner was a failure because “the fish was brought in before we had finished the soup & champaine glasses were furnished us to drink our brandy from & vice versa.” Murray was placed in irons and placed in the anchor well until sober. Yet, Murray would be drunk again the next day.[6]

While serving on Monitor during the expedition up the Appomattox River in late June 1862, Keeler complained to his wife that the move up that river was a failure because of two factors. The first: poor planning for the expedition. Various ships, including Maratanza, Southfield, Jacob Bell, and several others such as the submarine Alligator were part of the operation and did not coordinate their actions effectively. The ships ran aground and did not attain their mission. As soon as the officers “assembled on the PORT ROYAL, the second cause of the failure manifested itself–WHISKEY. They got around the Ward Room table & drank till every shot fired by the sharp shooters sounded like a thirty two pounder & the reports were multiplied indefinitely. Under these circumstances the expedition was given up & they returned on board their respective vessels with fearful stories of narrow escapes from the myriads of sharp shooters.”[7]

Our Drunken Captain

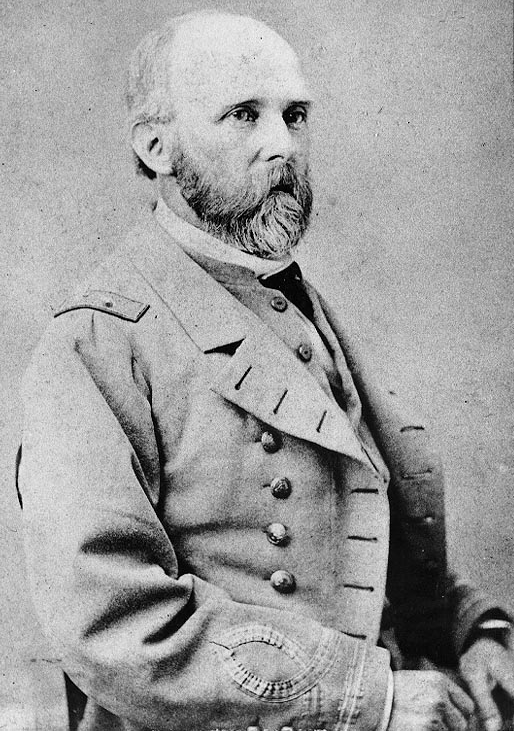

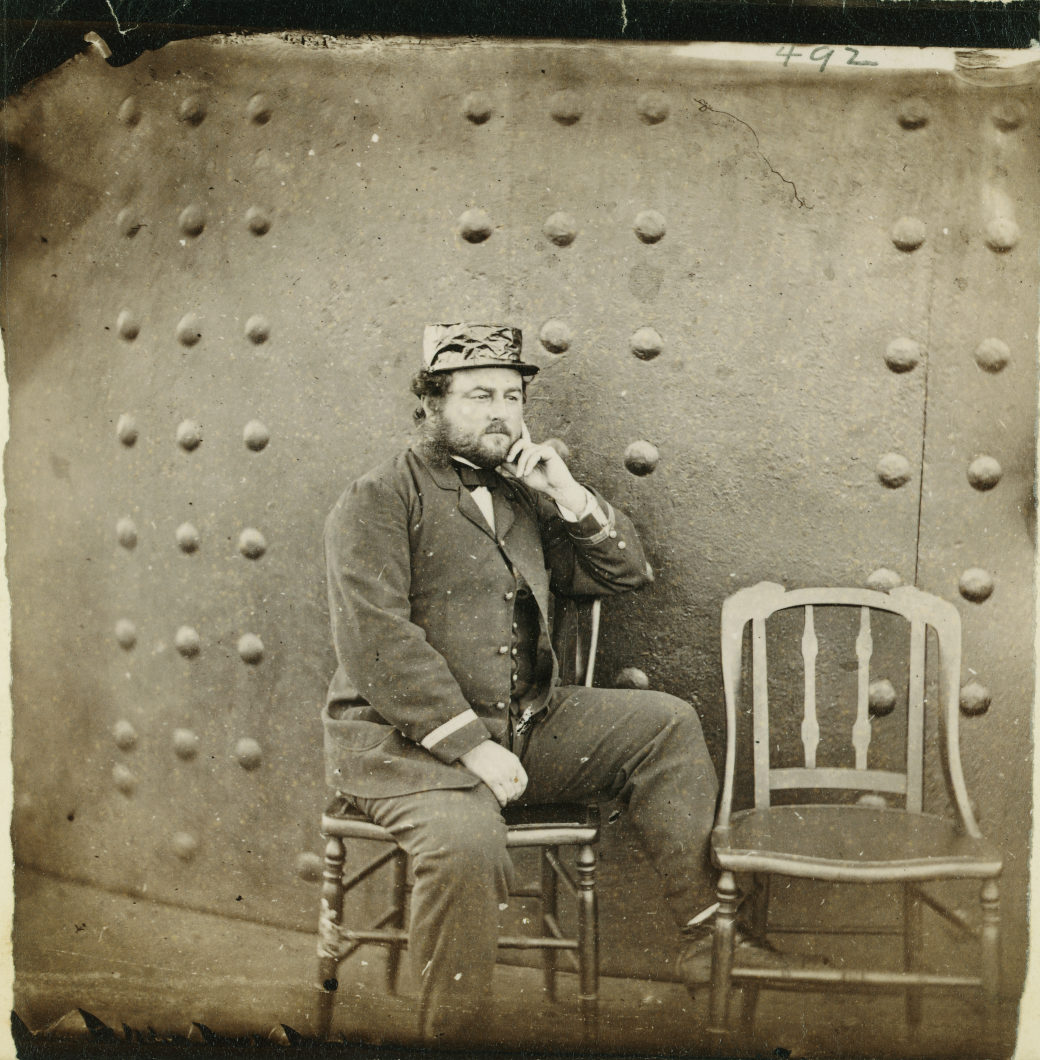

The Monitor’s fourth commander, Lieutenant William Jeffers, was not well-liked by the ironclad’s crew. They were happy to see him replaced by Commander Thomas Stevens Jr. Keeler noted that Stevens “has the appearance of a quiet modest man, so far I like him, but I find that first impressions are not always to be trusted. He has a reputation of taking a glass too much occasionally, the curse of the navy.”

Keeler remembered Stevens as commander of USS Maratanza during the drunken expedition up the Appomattox River. Stevens often drank without care, and more than once, he would call a sober officer at the Ward Room table, “I know you an abstemious man; but, I am not, so please pass me the whiskey.”

Stevens was replaced as Monitor’s commander on September 15 by Commander John Pyne Bankhead due to a drinking incident a few days before. Commander Stevens was too drunk to entertain several distinguished visitors, including Captain Thomas Turner. Turner, USS New Ironsides’ commander, was a member of the Naval Temperance Society and reported Stevens as having fallen down drunk upon meeting these dignitaries. [8]

A Little Too Groggy

Drinking caused numerous incidents that impacted the lives and careers of many of ‘The Monitor Boys.’ Lawrence Murray, the wardroom steward talked about earlier, was generally drunk as often as he could be. One day in September, he became drunk on shore leave, and when he returned to Monitor, he took an axe and tried to spit Keeler’s servant’s head open. Murray was placed in double-irons but somehow managed to the ship’s side and jumped overboard. The heavy irons doomed him, and his drowned body was discovered three days later, on September 5, 1862. Fireman George Geer noted that no one would lament his loss, as all Lawrence Murray did was drink and gamble his time and money away without sending support to his wife and child in California.[9]

When Monitor went for a refit at the Washington Navy Yard, the crew members were given liberty; however, some deserted rather than serve again on the ‘cheesebox on a raft.’ Some slipped away, never to be heard from again; however, a few did not return due to drinking episodes. Seaman Hans A. Anderson was about to return to Washington, DC, from New York City, when he “fell in with some men and went into a rum hole, and took a glass of beer which was evidently drugged.”[10] He soon found himself shanghaied on an unknown barque sailing to London. Anderson eventually made his way to a US consul, returned to the United States, and surrendered himself to the Navy. He was allowed to return to duty and, except for loss of pay while absent from duty, was not penalized for his drunken misadventures.

Drinking Dusty Durst

Coal heaver Wilhelm Durst was given two weeks liberty and spent his leave in Philadelphia and New York City, where he became ill. He claimed his illness to be typhoid fever, but he also believed he was “sick for some trouble to my heart and stomach, contracted from the bad air on the MONITOR.” Regardless, he was unable to return to duty and did not know what to do. Durst went out drinking one day, shortly after that: “I was taken in charge of by a ‘runner’ and the next thing I knew I was on board the NORTH CAROLINA. I asked for an explanation and was informed that I had been shipped under the name of Walter David, that there was nothing for me to do but to serve out my enlistment for one year.” (Wilhelm Durst’s ‘WD’ tattoo earned him the alias of ‘Walter David.’)

The new Walter David then shipped on the monitor USS Catskill where he was discovered by many of his fellow ‘Monitor Boys’ like Hans Anderson. “I knew him as soon as I saw him and called him Durst.” Anderson added, “He laughed and said that that was his name once, while on the LITTLE MONITOR but now…they call me Walter David…I called him Durst…and he was sometimes called the Dusty Jew.”[11]

The charge of desertion from Monitor was dropped, as the Navy Department noted: “Durst was of foreign birth and unaccustomed to the ways of his adopted country,” and that he had “in fact served in the navy during almost the entire period of the Civil War.” Durst would always be proud of his service, even though he never stopped enjoying a drink.

A Bad Day For Some: August 31, 1862

As the Temperance Movement gained strength, the US Navy ordered that the last grog ration be served on August 31, 1862. Commander Stevens, who was well known as an “intemperate man,” ran afoul of Congress’s new act that ended the twice-daily grog ration. The act stated that no liquor would be allowed on US Navy vessels except for medicinal purposes. Stevens, a heavy drinker, did not meet the medical requirement for receiving grog.[12]

Fireman George Geer did not drink and sold his grog ration (3 cents a day) to other crew members. Geer wrote to his wife with disdain about Captain Jeffers and how he tried to circumvent the new law before he was reassigned. “[He] is going to do something he thinks is smart. The new law about liquor says NO liquor shall be brot [sic] on any government vessel after 1st of September but says nothing about what is on hand at the time, so our Captain has sent for three 40-gallon barrels to have on hand. That is enough to last us one year. I hope the government will catch him at it someway, and make him trouble. I hope that he will get his deserts [sic] yet, before the war is over.” [13]

Don’t Give Up The Drink

Once the grog ration ended, sailors still sought some sort of alcoholic relief. Sometimes they received small whiskey bottles as gifts mailed to them; however, one of the best ways to become intoxicated was to obtain spirits in other sources. Bitters were patent medicine containing herbs and roots preserved using ethyl alcohol to maintain “medicinal properties” of the extracts.

S.T. Drake’s 1860 Plantation X Bitters and Dr. J. Hosteller’s Stomach Bitters were popular grog substitutes. Dr. Jacob Hosteller was from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and a graduate of Jefferson Medical College. His son sold his extract as “a positive protective against the fatal maladies of the Southern swamps, and the poisonous tendency of impure rivers and bayous.” It claimed to be for digestive disorders, and it was a potent 47% alcohol/ 94 proof. The sailors loved it! [14]

The US Navy took on the duty to stop the smuggling of whiskey and other alcoholic beverages. On February 23, 1863, Lt. Commander Edward P. McCrea of the gunboat USS Jacob Bell, learned that a sutler’s schooner Mail was discovered at Alexandra, Virginia, with a shipment of 428 dozen cans of “milk drink” made by Numsen, Carroll & Company of Baltimore. The cans were destined to be delivered to three Maine regiments serving near Belle Plain, Virginia.

McCrea called it “villainous eggnog.” Commodore Andrew A. Harwood, commander of the Potomac Flotilla, advised Acting Master A. J. Frank of the USS Wyandank: “You will observe that the cans of the kind are not soldered in the usual way. The top and bottom are probably heated with some resinous substance and the edges bent over in order that the cover at either end can be easily removed to convert the can into a drinking cup.” Harwood ordered Mail to be seized, like all other ships smuggling alcohol, and be sold at prize court with the profits going to the federal government. [15]

‘Black Tot Day’

After almost 80 years of official drinking in the US Navy, the practice ended with more than just a whimper. It continued in the Royal Navy until Black Tot Day in 1970. This day is still honored in the 21st century, mourning the last day the small grog ration (tot) was served.

Traditions lasting hundreds of years simply do not just fade away. Grog remains commonplace in our language with sayings like “Mind your P’s & Q’s” (pints and quarts), or British sailors being called “limeys” because of the use of limes in their grog. Nevertheless, thoughts of grog remain when dreaming about life at sea during the days before the mast.

DIY Grog

VICE ADMIRAL SIR EDWARD ‘OLD GROG’ VERNON’S

CAPTAIN’S ORDER NUMBER 349

2 ounces dark rum

4 ounces hot water

Suggested additions:

1 teaspoon brown sugar

1/2 ounce fresh lime juice

(By 1795, Dr. Thomas Trotter understood that citrus juice was a cure for scurvy and approved the addition of lime juice. He also thought adding a cinnamon stick made the concoction even tastier!)

Endnotes

- William R. Cline, “Ironclad Ram VIRGINIA,” Southern Historical Society Papers,” 32 (December 1904) p. 246.

- Robert W. Daly, ed., Aboard The USS MONITOR: 1862 The Letters Of Acting Paymaster Wiliam Frederick Keeler, U.S. Navy To His Wife, Anna, Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute Press, 1964, p.209

- B.L. Ranft, The Vernon Papers, London: Naval Records Society, 1958, pp.417-19.

- Brian Vale and Griffith Edwards, Physician To The Fleet, The Life And Times Of Thomas Trotter 1760-1832, Woodbridge: The Boyhill Press, 2011, pp.29-33.

- USS Southampton Log, 1848, National Archives.

- Daly, p. 21.

- Daly, pp. 22, 209.

- IBID.

- William Marvel, The MONITOR Chronicles, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000, p.182.

- Marvel, 177.

- Irwin Mark Berent, The Crew Of The MONITOR: A Biographic Dictionary, Raleigh, North Carolina: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1985, p. 34.

- IBID., p. 79.

- Marvel, p. 156.

- www. nps.gov/mwac/bottle_glass/hosteller.html

- Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Navies In The War Of The Rebellion, ser.I, vol. 5, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897, pp. 233-234.