This is a continuation of the story I shared in another blog about the Burnside Expedition and the battle for the NC Sounds and the capture of Roanoke Island.

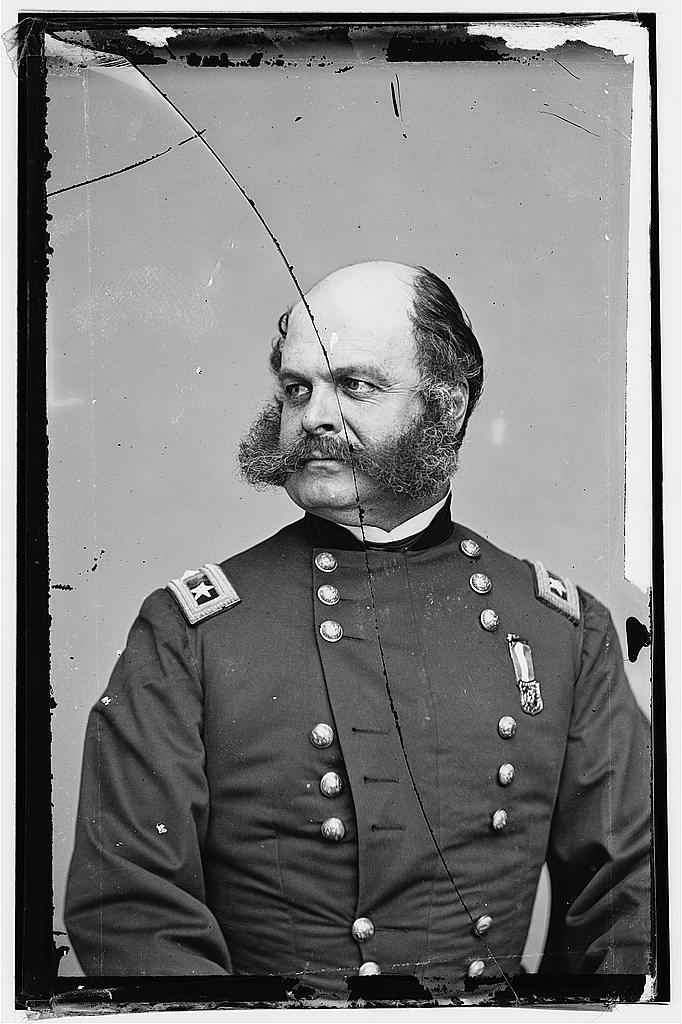

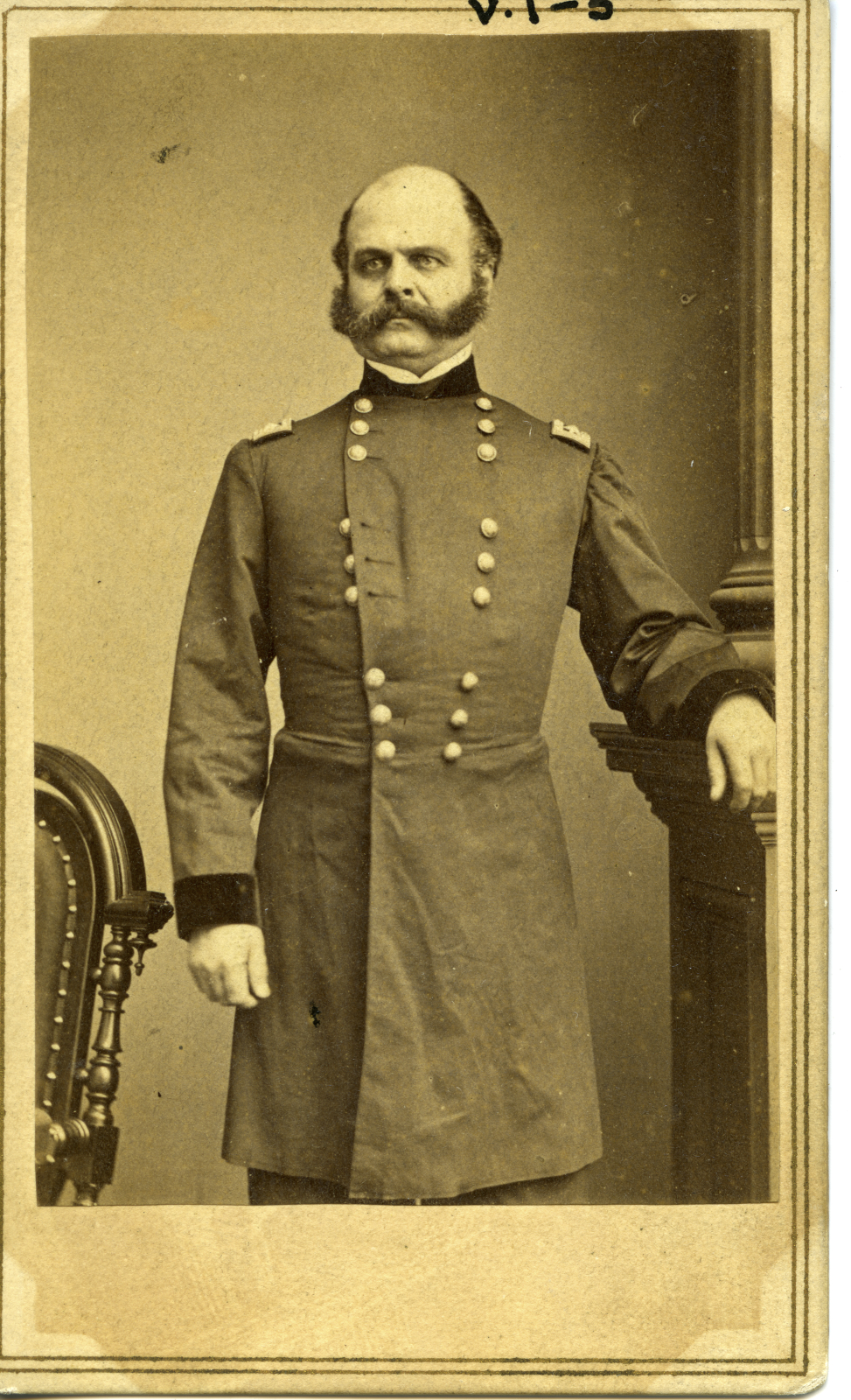

Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside’s invasion of the North Carolina inland seas was a major success. In seven days, Burnside, with the support of Flag Officer L.M. Goldsborough’s naval forces, had captured Currituck, Albemarle, Roanoke, and Croatan Sounds. This placed Burnside’s army in a position to capture his next objective, New Bern, North Carolina.

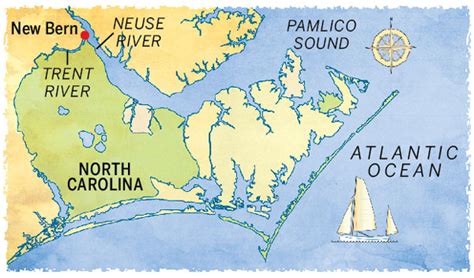

New Bern, North Carolina

New Bern (often spelled Berne in the 19th century) was a river port near the confluence of the Trent and Neuse Rivers, 37 miles from Pamlico Sound. Once the capital of North Carolina (1770-1792), it was the state’s largest city in the first quarter of the 19th century. Major General George B. McClellan recognized New Bern as an important military target, and his initial orders to Burnside included the capture of New Bern. Serving Pamlico Sound and North Carolina’s Piedmont region, New Bern was located on the Atlantic & North Carolina Railroad, making it a vital transportation center.

Fortifying New Bern

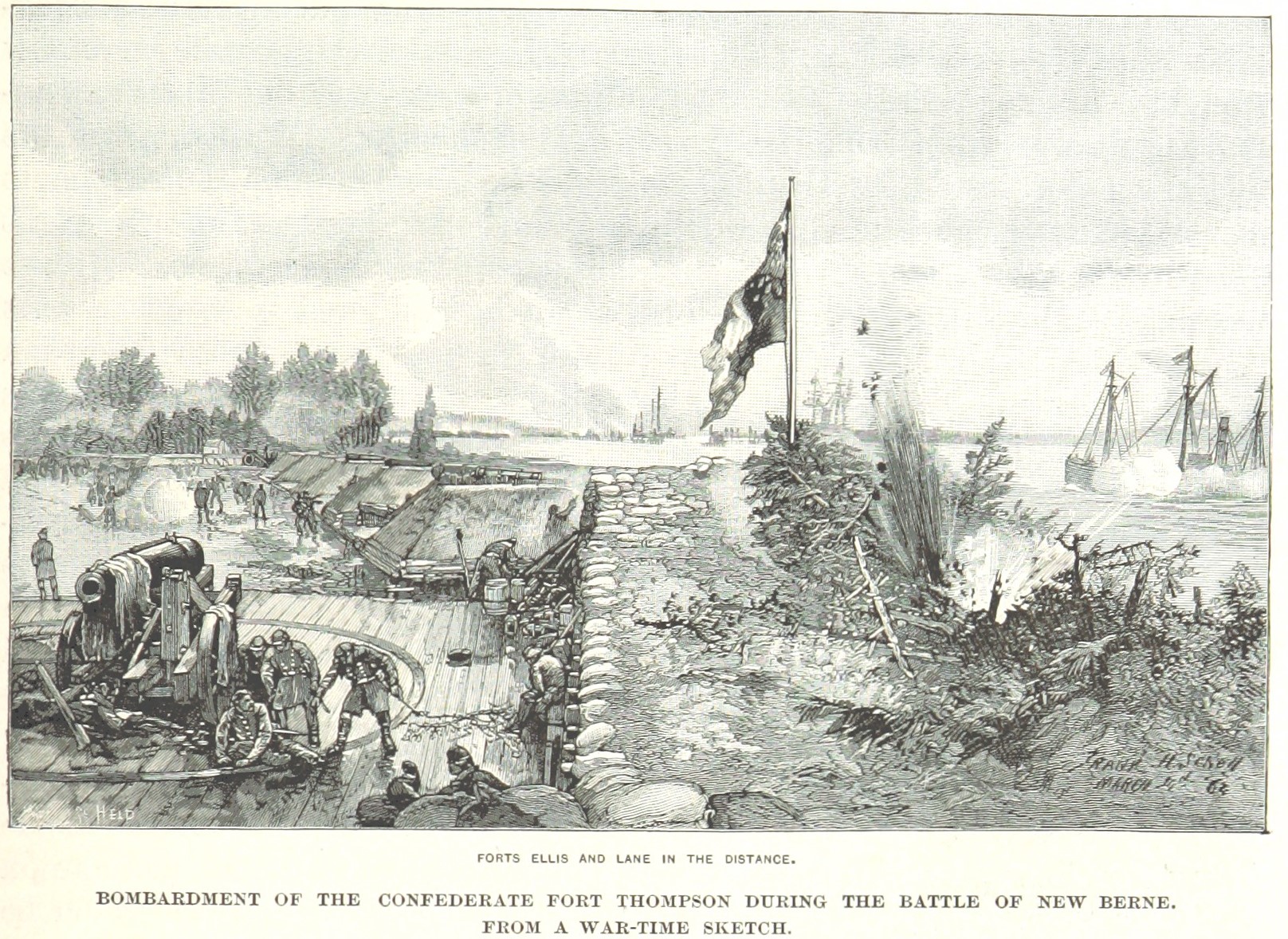

The Confederates, too, realized New Bern’s importance. D.H. Hill had organized the city’s defense beginning in October 1861 before he was detailed back to Virginia. Hill first developed two lines below the Trent River from New Bern. The first was called the “Croatan Line,” which went from Otter Creek to the railroad. Six miles closer to the city was a more complex system of earthworks anchored on a large earthwork named Fort Thompson overlooking the Neuse River. The fort had 13 heavy guns. Three defended the land approach, and the rest were focused on the river.

Nine other earthworks were constructed to protect the water route to New Bern, including Forts Brown, Ellis, Allen, Lane, and Dixie, maintaining 41 heavy guns. Two barriers blocked the river’s main channel. The first, emplaced a mile and a half below the fort, was a double row of 30 torpedoes. Each torpedo contained 200 pounds of powder. The second line was installed just opposite Fort Thompson and consisted of sunken hulks and chevaux de frise. This barrier was designed to force attacking ships under the guns of the water barrier. While the land defenses extended to the railroad, the Confederates expected the main Federal attack to come by the river.[1]

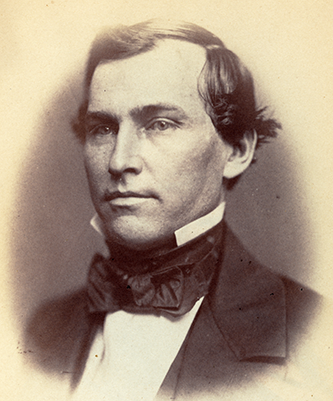

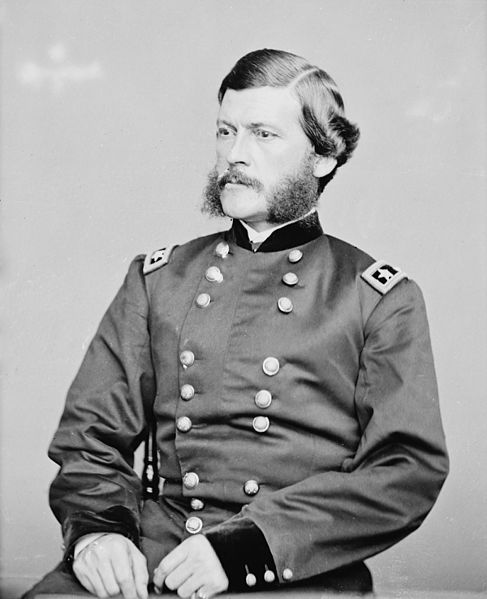

A New Commander

Brigadier General Lawrence O’Bryan Branch assumed command of the Pamlico Sound District when Hill returned to Virginia. Branch was a native of Enfield, North Carolina; however, his parents died when he was young, so he was raised by his uncle, former governor of North Carolina John Branch. When the elder Branch served as Secretary of the Navy, Lawrence went to Washington City with his uncle and was tutored by Salmon P. Chase before graduating from Princeton in 1838. He later served in Congress from 1855 to 1861. When North Carolina left the Union, Lawrence O’B. Branch was appointed quartermaster and paymaster-general of the state. He resigned from this position to become colonel of the 33rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment. Branch was promoted to brigadier general on November 16, 1861. It was General Branch who was responsible for defending against Burnside’s advance. [2]

Burnside Makes His Move

Burnside had spent the time following Roanoke Island’s capture consolidating his control over North Carolina’s upper sounds. Most river ports submitted without resistance. Winton, North Carolina, tried to spring a trap on eight Union gunboats and the Hawkins Zouaves. The subterfuge was uncovered just as USS Delaware pulled up to the main dock. The Delaware sheared off, regrouped, and then sacked Winton on February 18, 1862. [3] Burnside’s next target was New Bern, down the Pamlico Sound from Roanoke Island. The Federals embarked 11,000 soldiers from Roanoke Island on March 11, 1862, and sailed in perfect weather toward the Neuse River’s mouth.

A New Naval Commander

Union naval forces in North Carolina waters had changed leadership. Flag Officer L. M. Goldsborough had been recalled to Virginia to respond to the emergence of CSS Virginia in Hampton Roads. The situation in Virginia had deteriorated just on the eve of Gen. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign. Commander Rowan assumed leadership of the Federal flotilla in North Carolina. Rowan, a very aggressive leader, was determined to gain greater glory for the USN during this campaign. Union gunboats left Hatteras Inlet on March 11 and arrived in the Neuse River on March 12. Rowan switched his flag to USS Philadelphia.[4]

Confederate Troop Dispositions

The Southerners expected that the main Union attack would come by way of the river. They were ill-prepared for any Union infantry assault. The Confederacy had more than a month to enhance New Bern’s defenses or troop strength even though the Union threat loomed. Branch only had 4,500 soldiers to guard the port city. Consequently, Branch had to abandon the stronger “Croatan Works” and fell back to a previously prepared position that was weaker due to the topography. The interior defensive line extended from Fort Thompson, defending Beaufort Road, and reached the railroad. The 35th, 7th, 37th, and 27th North Carolina regiments filled this position.

Branch recognized that he had to extend his right to anchor his flank. He then moved Colonel Zebulon Vance’s 26th North Carolina to create a defensive position along a small creek known as Bullen’s Branch and rested its flank on marshes near Bryce’s Creek. The line then dog-legged to meet the railroad and the flank of the 35th North Carolina. This was the weakest point in Branch’s defensive position and was known as Wood’s Brickyard. This section’s defense rested on a brick kiln. To make matters worse, it was manned by a recently organized battalion of militia commanded by Colonel H.J.B. Clark. These men were poorly armed and inadequately trained; yet, they were positioned in a critical position. Colonel C.M. Avery’s 33rd North Carolina was placed in reserve.[5]

Slocum Creek Landings

In the afternoon of May 13, Rowan’s gunboats went into action. The Stars And Stripes and Louisiana operated along the Neuse’s west bank; Valley City and Hetzel were on the river’s east bank. Gunboats cleared the shoreline of Confederate skirmishers as the troops waded ashore in dense fog. They landed in a “mud hole” as the roads “were rivers of mire.” [6]

Robert Dollard noted ”that the North Carolina soil…in connection with a good vigorous rain, is a combination hard to beat….at it’s best it seemed as though when one got his foot stuck in the mud and attempted to get it out it was a question whether the mud or ankle would give way.”[7]

Alfred Roe of the 24th Massachusetts penned a simple verse on the evening of March 13:

Now I lay me down to sleep

In mud that’s many fathoms deep

If I should die before I wake,

Just hunt me up with an oyster rake. [8]

Gunboats Speak

The Army was unable to move its heavier artillery in support of their advance. So, Rowan added some firepower to the Federal advance by sending ashore a battery of six boat howitzers commanded by Lieutenant Roderick Sheldon McCook. His men struggled to drag the guns through the mud and the help of Union troops to keep up with the advance.[9]

The most effective naval support was from the gunboats. Naval gunnery pushed the few Confederates assigned to contest the Union landing back toward the Croatan Line. As the IX-inch shells screamed into Confederate positions, they abandoned that defensive position, fearing that Union gunboats would flank them. Commander Rowan’s aggressive gunnery tactics were much like a creeping barrage. Gunboat projectiles often fell near the advancing Union men “splintering and cutting off trees, and poughing great furrows in the ground.” [10] Rowan instructed his ships to fire as closely as possible to the advancing Federal lines.

Rowan wrote Goldsborough: “I commenced throwing 5,10, 15 second shells inshore and notwithstanding the risk, I was determined to continue until the general sent me word. I know the persuasive effect of a 9-inch, and thought it was better to kill a Union man or two then lose the effect of my moral suasion.” [11] Union troops attempted to guide the naval gunfire using rockets with limited effect.

The Assault Begins

Dense fog covered the ground on the morning of March 14 when Burnside ordered his men to advance. Union gunboats continued to shell Confederate lines; however, the Federals were unsure of the defender’s actual disposition. General Foster’s brigade was to strike at the Confederate right moving down the muddy Beaufort Road.

Ambrose Burnside hoped that Foster’s troops could break through near Fort Thompson. Foster supported his attack with a battery of six boat howitzers commanded by Lieutenant R. Sheldon McCook. These guns were difficult to deploy. The primary artillery support came from gunboats sending shells into both Confederate and Union formations until Burnside told Rowan to stop.[12]

The Brick Kiln

Foster’s brigade fought to a standstill in front of the Confederate lines with musketry and cannon fire so heavy that the wind took all the smoke and commingled it with the fog. This circumstance made it difficult for Reno’s brigade to advance along the railroad. Reno thought that the Confederate line’s flank was in the air beyond the railroad line, so he ordered the 21st Massachusetts to attack the brick kiln.

Branch realized the weakness of his troops at the brickyard and sent two 24-pounders to support the poorly-trained militia. These guns were not placed in position when Reno’s assault struck the Confederate lines. The power of the 21st’s attack broke through the militia lines and captured the battery before it was unlimbered. The regiment’s commander suddenly realized that he was virtually surrounded by elements of 26th and 35th North Carolina regiments. Reno had his Massachusetts troops firing all day along this part of the Confederate line, and a temporary stalemate ensued. [13]

The Breakthrough

Reno and Clark thought that one more push would win the day for the Federals. Colonel Isaac P. Rodman of the 4th Rhode Island asked 3rd Brigade commander General John Parke, who was holding his troops in reserve, to attack. Rodman’s assault was successful and broke through the brickyard, captured nine cannons, and forced the militia to run away. This action opened up the flanks of the right and left of the Confederate line and forced the Confederates to retreat in a somewhat disorderly fashion burning the Trent River bridge. This isolated the 26th Carolina. This caused Vance to send his troops across Byrce’s Creek to escape from the battlefield. Branch could not gain control of his command until they reached Kinston, North Carolina. [14]

“Follow My Motions”

As the Confederate land defenses collapsed, Rowan steamed his gunboats through the river obstructions. The torpedoes did not work; however, the iron-capped piles were somewhat effective. “The Commodore Perry struck one of the iron stakes and carried the head of it off sticking in her bottom. The Commodore Barney had a hole six inches long cut in her, and the Stars and Stripes was also injured.” [15]

Despite these damages, Rowan was able to ensure that all of the Confederate batteries had been abandoned. When his squadron reached New Bern’s waterfront, Rowan took “possession of an immense amount of stores, arms, munitions, vessels and cotton and lots of pitch and tar….the town is an immense depot of army fixtures and manufacturers, of shot and shell, carriages, etc.” [16]

Burnside had achieved another great victory. His Coastal Division was within striking distance of the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad at Goldsboro, and Beaufort, one of North Carolina’s major ports, was within reach. Burnside decided to move against Beaufort as he needed to improve his supply connections. Hatteras Inlet was not as fine a port as Beaufort, and Burnside knew he had to resolve re-supply issues to consolidate his control over Eastern North Carolina.

A Pair of Port Towns

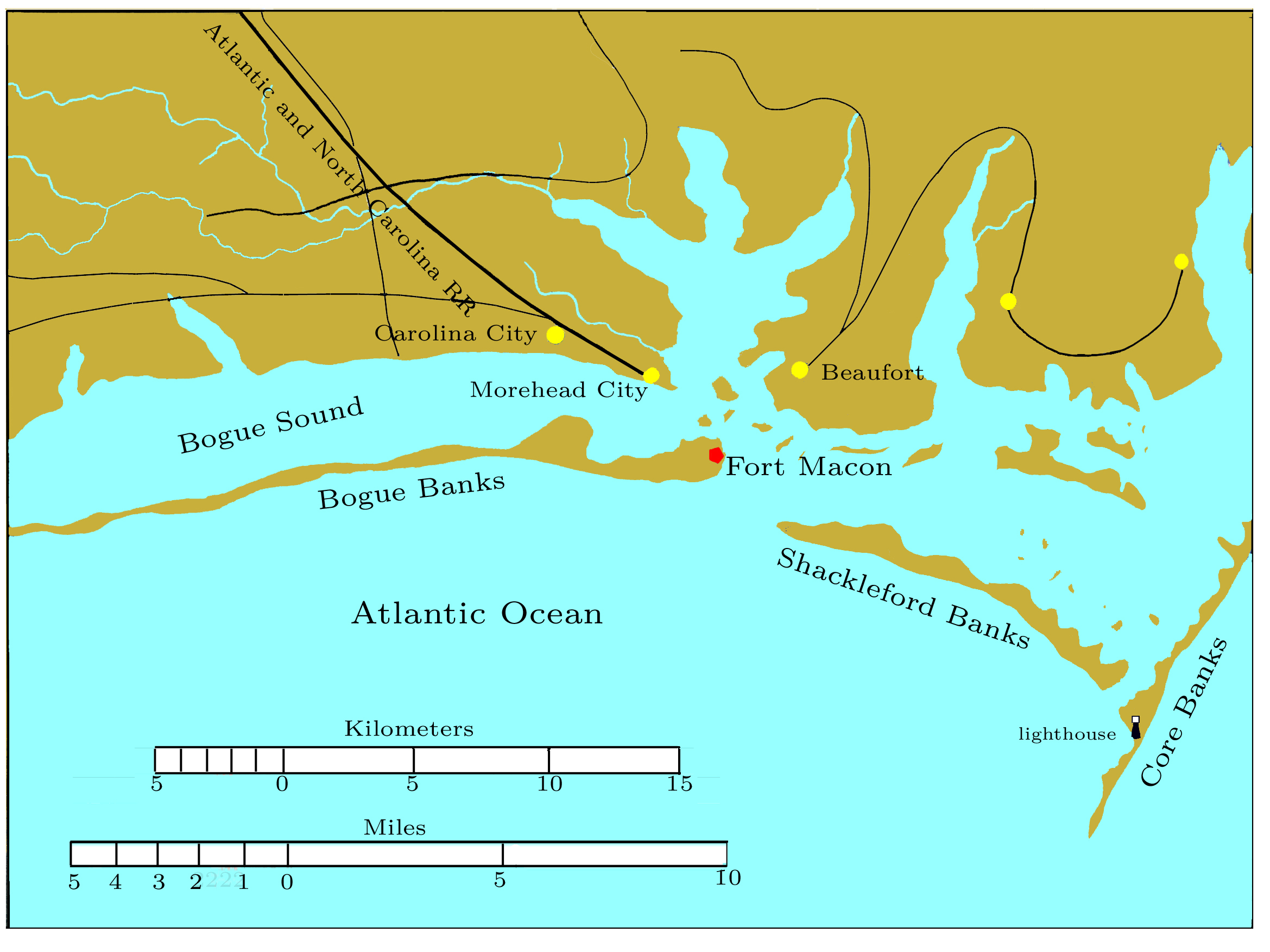

Beaufort is one of North Carolina’s oldest communities and one of the state’s best deepwater ports. Morehead City, a new port developed in the 1850s, was linked to the state’s interior by the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad. Burnside would complete his conquest of Eastern North Carolina with the occupation of these two towns. However, to do so required the Coastal Division to conquer Fort Macon on Bogue Banks overlooking Beaufort Inlet (Old Topsail Inlet).

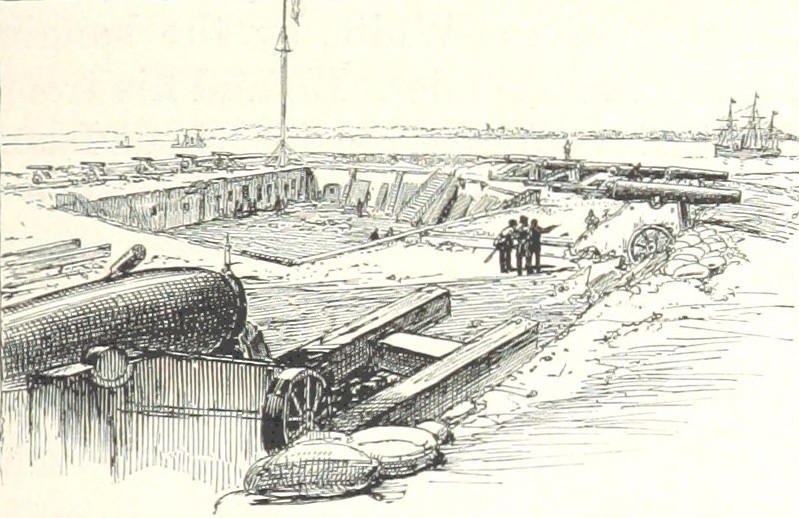

Crumbling Fort

Fort Macon is a Third System coastal defense fortification built to replace the 1809 Fort Hampton. A severe hurricane destroyed Fort Hampton in 1815. Its replacement, Fort Macon, was named in honor of Nathaniel Macon, former Speaker of the US House of Representatives and a US Senator from North Carolina.

This pentagonal brick fort was designed to mount 56 heavy guns placed en barbette to defend access to Beaufort. Begun in 1826 and garrisoned in December 1834, Fort Macon never became a major installation, and for most of its antebellum lifespan, only one ordnance sergeant was detailed to maintain the fort. When the secessionist crisis struck, the local militia, commanded by Captain Josiah Parker, took over the fort on April 14, 1861. This action occurred even before North Carolina left the Union a month later. [17]

Fort Macon Revived

The Confederates immediately set forth to repair, rearm, and improve the fort. In 1861, Fort Macon only had four guns mounted on rotting carriages. Crumbling brick, rusted iron, and worthless wooden structures plagued the defensive work. Lieutenant Colonel John L. Bridgers, who fought with the 1st North Carolina at the June 10, 1861 Battle of Big Bethel, was the fort’s first commander. Bridgers endeavored to make repairs and secure more artillery. He made arrangements for Lieutenant William H. Parker, CSN, to train the volunteers to service the heavy artillery.[18]

Change in Command

Ordnance officer Colonel Moses J. White replaced Bridgers as Fort Macon’s commander on October 5, 1861. White, a native of Vicksburg, Mississippi, attended the College of William & Mary and graduated from the USMA in 1858. The new commander was in poor health and suffered from epilepsy.[19]

Nevertheless, White placed renewed enthusiasm preparing the fort for combat. By early April 1862, repairs had been completed, and 56 guns had been mounted, including two 10-inch and five 8-inch Columbiads, nineteen 24-pounder howitzers, thirty-two 32-pounders, and six 12-pounder howitzers. Four of the 32-pounders were rifled. White lacked any mortars, and the hot shot furnace was somewhat outdated. Even though there was plenty of ammunition, the fort contained only enough gunpowder for three days of sustained action. White had secured seven months of food supplies to support Fort Macon’s garrison of almost 440 men. [20]

Since the fall of New Bern, Col. White prepared the fort for a Union siege and bombardment. Sandbags were filled, buildings, like the Eliason House, in the fort’s field of fire were destroyed, the Beaufort Light was pushed over, and the railroad bridge over the Newport River was burned.

The Last Escape from Beaufort

As General Parke’s brigade and siege train approached Beaufort, White supported the escape of the infamous Confederate commerce raider CSS Nashville. When Nashville prepared to run out to sea, White suggested that the ship be burned to avoid capture and its crew added to Fort Macon’s garrison. Time was running out for Nashville as advance elements of the Coastal Division reached the new community of Carolina City, overlooking Bogue Sound. Lieutenant William Conway Whittle, CSN, the commerce raider’s executive officer, had little desire for his ship to be captured.

The Nashville anchored off Fort Macon to await the opportunity to escape. Whittle would break out on March 17, 1862. He steamed his ship directly toward USS Cambridge and passed by the gunboat as the other blockader, USS Gemsbok, merely looked on. The garrison cheered Nashville as the steamer passed, unharmed, out to sea. [21]

Currier & Ives. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

‘Decline Evacuating Fort Macon’

Parke orchestrated the capture of Carolina City, Morehead City, and Beaufort between March 21-25. This completely isolated Fort Macon. General Parke sent a message to Col. Moses demanding the fort’s surrender. The Union general wanted to “save the unnecessary effusion of blood” and advised that he had “intimate knowledge of the fort.” Moses tersely replied, “I have the honor to decline evacuating Fort Macon.” [22] Col. White’s defiant stance prompted a member of Fort Macon’s garrison to write:

“If Lincoln wants to save his bacon

He’d better stay away from ol’ Fort Macon.”[23]

Crossing the Sound

General Parke now had no alternative but to lay siege to Fort Macon to force its surrender. Parke selected a landing site on Bogue Banks called Hoop Pole Creek, located just four miles south of Fort Macon. Since Bogue Sound was not very deep, the Federals had to use two shallow-draft steamers, Ellis and Old North State, to transport, sometimes using barges, more than 3,000 soldiers, and 11 siege guns. This was an arduous task, which took several days of intensive work to get the artillery through the creek’s marshes onto dry land. [24]

Isolation

The sense of isolation was telling on the garrison. There were several deserters, and sickness prevailed. The garrison was listed as having 430 officers and men; however, there were just 263 men ready for duty on some days. This lack of manpower limited White’s ability to block Federal infantry advances toward the fort. The 26th North Carolina Infantry served on Bogue Banks to support the fort’s defenses. Nevertheless, General Branch‘s need to raise more troops for the defense of New Bern resulted in the 26th being transferred to Branch’s defensive lines outside New Bern. This enabled the Unionists to begin constructing their siege lines without much interference from Fort Branch’s garrison.

Planning the Seige

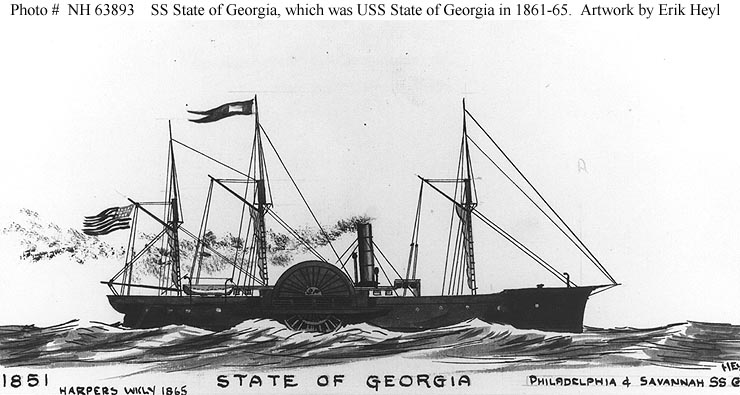

On April 11, elements of the 4th and 5th Rhode Island Battalions began advancing toward the fort. Accompanying this advance was Brigadier General John G. Parke and some key members of his staff: Ordnance Officer Lieutenant Daniel W, Flager, Topographical Officer Captain Robert S. Williamson, and commander of Company C, 1st US Artillery Captain Lewis O. Morris. These men would plan where the batteries needed to be placed within Bogue Banks’ dunes. The Confederate skirmish line was pushed back toward Fort Macon, outnumbered by the Rhode Islanders, and ships from the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron began shelling the retreating soldiers. The steam screw gunboat USS Albatross, with its five guns and the sidewheeler State of Georgia, provided additional gunfire with its nine guns. As the warships and Union troops neared, Fort, Macon opened fire. The fort was able to force the Union forces to retreat. Despite all of the musketry and booming of cannons, Parke and his staff could select siege lines required for the necessary heavy artillery.[25]

Building Batteries

Parke established an advance picket line 1,200 yards from the fort, manned initially by the 10th Connecticut. The infantry was supported by a 12-pounder Dahlgren boat howitzer manned by naval personnel from Old North State. Behind these rifle pits, Parke arranged three different siege batteries:

Flagler Battery: Commanded by Lt. Daniel W. Flagler. Four Model 1841 10-inch mortars located 1,680 yards from the fort, weighing 5,800 lbs. with a range of 2,225 yards.

Morris Battery: Three 30-pounder (4.2-inch) Parrott rifles located 1,480 yards from the fort. These rifles weighed 4,200 lbs. and had a range of 6,700 yards. Commanded by Capt. Lewis O. Morris.

Prouty Battery: Four Model 1841 8-inch mortars located 1,280 yards from the fort. These mortars weighed 930 lbs. and had a range of 2,064 yards. Commanded by Lt. Menick F. Poultry. 26 OR, Ser 1, Vol. 9, 273-286]

General John Parke had a mixed assortment of siege guns that could strike at Fort Macon using direct and indirect fire. The mortars were fired at high-arcing trajectories. Generally, a mortar shell would hit within 50 feet about 50 percent of the time. Parrott 30-pounders offered a very straight and low trajectory and using solid shot bolts or shells. Invented by Robert Parker Parrott, this rifle was very accurate. The cast-iron tube was reinforced with a wrought iron band. The 30-pounder Parrott rifle was the most popular siege rifle as it had a lesser propensity to bursting as found in larger caliber Parrott guns. Shot from these rifles would bore into a fort’s masonry walls, making all these defense brick forts obsolete by 1862.[27]]

Building and arming these batteries was an arduous task. The heavy artillery had to be moved four miles and dragged through heavy sand to their position to shell the fort. The guns were emplaced at night as the Confederates would shell exposed work parties throughout the day. Construction of the battery was also tough work. Three dunes were used. Soldiers dug away at the interior face of each dune. Sandbags were used to support the position, and wooden timbers supported the siege guns. While mortars could easily shoot over a dune to reach their target, the Parrott rifles needed embrasures that could not be created until just before the bombardment began. It was a 10-day process; however, by April 23, the guns were ready to strike at the fort. [28]

White Attempts a Defense

Colonel White knew that the Federals were building gun emplacements; unfortunately, he did not have any mortars to drop shells behind the dunes. Accordingly, White took six 32-pounder carronades and mounted them on Fort Macon’s land face. The carronades were positioned at an elevation of 40 degrees so that they could simulate a mortar. Two 10-inch Columbiads on the fort’s sea face were turned around to fire at high elevation with low powder charges to also act as mortars. This counter-battery cannonade had little impact on the Federal batteries. [29]

Burnside Arrives

Now a major general, Ambrose Burnside toured Gen. Parke’s siege works with great satisfaction on April 18. Burnside had already advised the War Department that he hoped “to reduce the fort within ten days.” He advised Parke to place sharpshooters in the ruins of the Eliason House. As they moved down the beach to this position, they were spotted by Confederate artillerists and forced to retreat under heavy shell and fire.[30]

On April 23, Burnside returned aboard the steamer Alice Price. The steamer towed a schooner filled with ammunition and two old canal boats converted into floating batteries protected by wet hay and cotton. Both Grenade and Shrapnel were armed with four Parrott rifles and one Wiard rifle, an artillery piece with a range of 7,000 yards with a 3,67-inch bore, weighing 725 lbs. Only 60 were made during the war. [31]

Burnside wanted Fort Macon to be fired upon by three sides. Elements of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron in Beaufort Inlet, the floating batteries from Bogue Sound, and Parke’s three heavy batteries would undoubtedly force the fort to surrender.

The Olive Branch

Every gun was ready to fire on April 23; however, Burnside wanted a bloodless capture of Fort Macon. The general sent Captain Herman Briggs, Burnside’s Chief Quartermaster, under a face of truce, to meet with the fort’s commander. Briggs and White were friends from their days at West Point. Briggs met Lt. Daniel Cogdelll in Bogue Sound off Shackleford Banks to relay Burnside’s offer. Burnside wanted the fort intact and offered very reasonable terms. The Union general also advised in his offer that the Union siege guns were ready to fire, and he hoped to save human lives. Furthermore, he suggested to White that the consequences of the bombardment would rest upon the shoulders of Fort Macon’s commander. [32]

Upon receiving Burnside’s message, Col. White met with his officers, and they all agreed to fight rather than surrender. Cogdell took the reply back to Briggs. Then Briggs suggested that the two commanders meet the next morning on Shackleford Banks. It was agreed to do so. While the meeting was very cordial, it achieved nothing. Burnside warned White about the effects of the bombardment, destruction, and capture of Fort Pulaski by Union siege guns, and Burnside’s heavy artillery would do the same to Fort Macon. This news shocked White as he knew the brick fort below Savannah was a more powerful fort than Fort Macon. While he understood the implications of the breeching of Fort Pulaski’s wall upon his fort, White, nevertheless, was determined to defend Fort Macon as best and as long as he could. Burnside then ordered Parke to begin his bombardment on the fort. Minor preparations delayed the firing his siege guns until the morning of April 25. [33]

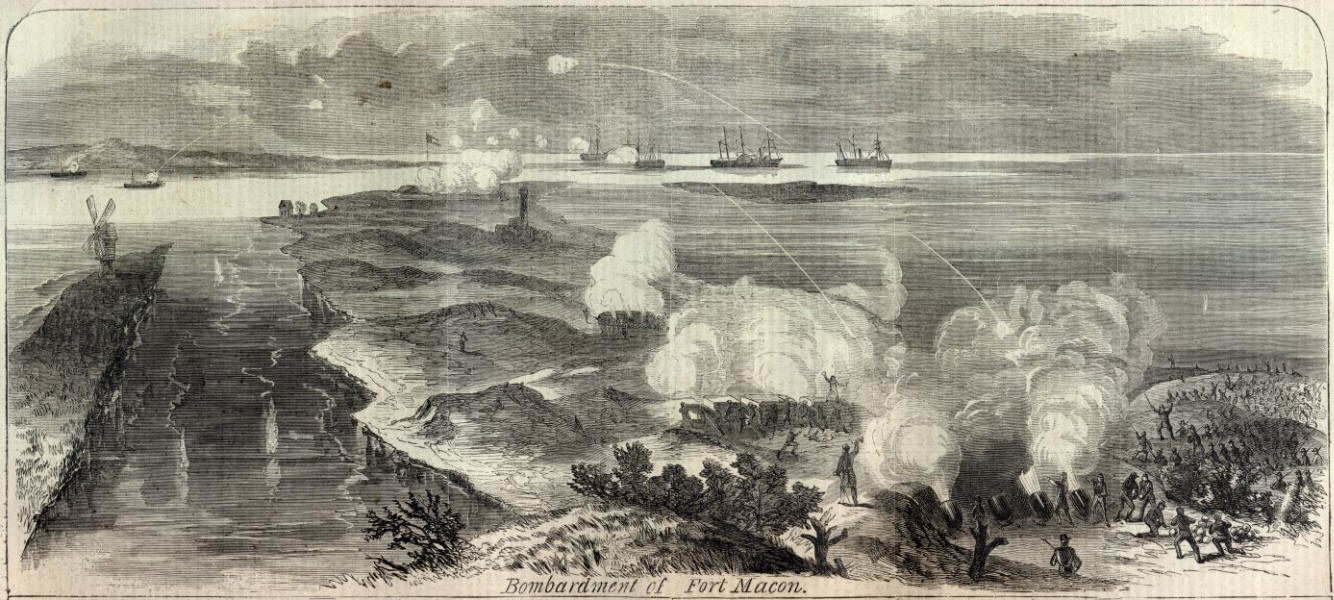

Bombardment Begins

At dawn on April 25, the first shot came from Morris’s Parrott Battery which struck the upper parapet and was quickly followed by shells from the mortar batteries. The fort returned fire by 6:00 a.m. using approximately 21 of its guns. Almost 200 men were on sick leave, which limited the fort’s response. Nevertheless, the fort replied rapidly; yet, the Confederate cannons had little impact on the Federal batteries. The fort’s gunfire shrouded its parapets with gunsmoke. Consequently, the Union batteries firing on the fort at this time could not tell where their shot was falling..[34]

Attack By Sea

At about 8 a.m., four Union warships approached Fort Macon. When Commander Samuel Lockwood heard the cannonade, he immediately moved his gunboats toward Beaufort Inlet. Lockwood’s goal was to provide direct fire at the fort. His ship, Daylight, was a screw steamer armed with four 32-pounders. Following his vessel in a line ahead was the sidewheeler State of Georgia captained by Commander James F. Armstrong and armed with six VIII-inch shell guns, two 32-pounders, and one 30-pounder Parrott rifle. Next came the screw steamer Chippewa commanded by Lieutenant Andrew Bryson. This Unadilla-class gunboat was armed with one XI-inch shell gun, two 242-pounders, and one 20-pounder Parrot rifle. The last ship in line was the bark Gemsbok, armed with four VIII-inch shell guns and two 32-pounders and commanded by Acting Lieutenant Edward Cavendy.[35]

These ships opened their attack upon the fort at 8:30 a.m. The Gemsbok anchored about a mile off the fort while the steamers moved back and forth in Beaufort Inlet. The conditions were deplorable as high winds rocked the vessels and disrupted their aim. Fort Macon was designed precisely to fight warships and was able to send a shell into Daylight’s starboard quarter. The shot rumbled through several bulkheads and deck while just missing the main steam line. Gemsbok had a shot through its rigging and a damaged mast. State of Georgia received a shot through its flag. Generally, the fort’s shot and shell ranged above or nearby the warships. After 75 minutes of action, Lockwood broke off the action, which caused Fort Macon’s garrison to resound with cheers.[36]

The Barge Attack

Efforts were made to bring the two floating batteries, Shrapnel and Grenade, into action. Heavy winds and seas allowed only the Grenade, commanded by Lieutenant Benjamin D. Baxter, to maintain a position to shell the fort. About 30 shots were fired from the batteries’ 30-pounder rifles. This shelling seemed to have no impact upon the fort, and soon both batteries dropped out of the battle. [37]

Correcting Their Aim

The initial bombardment from the dune batteries had limited success. Most of the Union shot, and shell overshot the fort smashing down into the inlet or tearing up sand on Shackleford Banks. Nevertheless, two intrepid US Signal Corps lieutenants, William S. Andrews and Marvin Wait, took the initiative to climb up to the upper balcony of the Atlantic Hotel in Beaufort and were able to signal the batteries with range corrections. This sharpened the Union gunners’ aim and took a toll on Fort Macon’s walls. Nineteen guns were knocked out of action. The Parrott rifles also proved to be highly effective, crumbling the fort’s brick walls. By mid-afternoon, White recognized a 12-foot crack in the fort, which threatened to breach the main magazine. At 4:30 p.m., a white flag appeared over Fort Macon’s parapet.[38]

Surrender Terms

Colonel White asked for surrender terms, to which General Parke replied that the only terms were unconditional surrender. White then requested the same conditions that Burnside had previously offered. Parke agreed not to continue the bombardment and would wait for Burnside to make a final decision. Burnside, who wanted no further damage to the fort, agreed that the US Army would take possession of Fort Macon and the garrison paroled. The defenders were allowed to take their personal property and could go home to await their exchange. About 10:10 a.m. on April 26, 1862, Col. Moses White marched his men out of the fort. Very quickly, the Stars and Stripes were once again flying over Fort Macon. [39]

Evaluating Victory

The siege was almost bloodless despite the intensity of the bombardment. The fort’s garrison suffered eight killed, 16 wounded, and 400 captured. The Union had also captured 54 artillery pieces, 2,000 pounds of gunpowder, vast amounts of commissary and quartermaster stores, 40 horses, and 500 muskets. In turn, Parke’s brigade had incurred one killed and 18 wounded.

Once the Federals took over the fort, Lt. Flagler and others sought to detail the bombardment’s effectiveness. Flagler reported that of 1,050 shots fired at the fort, 560 hits were made. They noted that 41 bolts pounded into the fort’s masonry walls. Some Parrott bolts reached a depth of two feet into the brick, and mortar shells exploded on the ramparts, parade ground, and ditch. Moses White later commented, “Two more days of such firing would have reduced the whole fort to a mere mass of ruins.[ 40]

Meaning of Burnside’s Expedition

Burnside had methodically captured North Carolina’s Great Inland Sea. He achieved such success because of his superiority in manpower and armaments and tremendous mobility provided by the US Navy. These strengths allowed Burnside to overwhelm poorly defended river ports easily. The Confederate government failed to appreciate the need to protect North Carolina from Federal advances. The divided Confederate command structure in North Carolina and the lack of concern and support by the Confederate government did not allow for an effective response to Union aggressive movements. Consequently, the Confederacy lost a major agricultural resource which weakened the Confederacy’s ability to wage war.

Burnside, the Hero

Major General Ambrose Everett Burnside emerged from his Carolina campaign as one of the most successful Union generals in Spring 1862. Although he accepted all of the laurels his victories brought him, Burnside knew he had a tremendous opportunity to end the war in 1862. The capture of Wilmington would end the port’s value as a blockade runner’s haven. In 1862 Cape Fear was not defended as well as it would be in 1864. Nevertheless, Burnside also recognized the value of capturing Goldsboro, North Carolina. Such a move would cut the railroad line coming from the Deep South, thereby isolating Richmond. The capture of Goldsboro would split the Confederacy in two. Richmond would have to be abandoned if this transportation link was destroyed. Burnside was organizing an attack on Goldsboro when most of his Coastal Division was ordered to Virginia. The failure for the Union was that it did not consolidate the victories in eastern North Carolina that could have yielded a decisive victory.

ENDNOTES

1.J. E. Kaufman and H.W. Kaufman, Fortress America: The Forts that Defended America, 1600 to the Present, Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2007, pp. 251-252; and Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of Rebellion, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1910, (Hereinafter cited as ORN), Ser. 1, Vol. 7, p.112.

2.Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders, Norwalk, Connecticut: The Easton Press, 1987, p. 31.

- Thomas C. Parramore, ‘The Burning of Winton in 1862,” North Carolina Historical Review, January 1962, p. 7.

- ORN, 1910, Ser. 1, Vol. 9, p. 110.

- William R. Trotter, Ironclads And Columbiads: The Civil War In North Carolina-the Coast, Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher. 1989, pp.110-114,

- Alfred H. Guernsey and Henry M. Alden, Harper’s Pictorial Of The History Of The Civil War, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1866, p.246.

- Robert Dollard, Recollections Of The Civil War, privately printed, p. 54.

- Alfred S. Roe, The Twenty-fourth Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers, Worcester, Massachusetts, 1907, p. 82.

- ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 9, pp. 113-114.

- Robert M. Browning Jr., From Cape Charles To Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron During The Civil War, Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 1993, p. 32.

- ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 7, pp. 111 and 117.

- IBID, p. 118.

- IBID, p. 244.

- IBID, pp. 223-228.

- IBID, p. 112.

- IBID. p. 118.

- Kaufman and Kaufman, pp. 218 and 239.

- William Harwar Parker, Recollections Of A Naval Officer, 1841-1865, New York: Charles Scribners’ Sons, 1883, pp. 215-220.

- George W. Cullen, Biographical Register Of The Officers And Graduates Of The United States Military Academy At West Point, New York, From Its Establishment In 1802 To 1890, With The Early History Of The United States Military Academy, 3 Vol., Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891, p. 700.

- W. C.Whittle Jr., “The Cruise of the C.S. Steamer NASHVILLE,” Southern Historical Papers, Vol. XX1X, p. 208.

- The War Of The Rebellion: A Compilation Of The Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Armies, Ser. 1, Vol. 9, pp. 227-228.

- Trotter, p. 137.

- New York Times, April 16, 1862.

- Paul Branch, Fort Macon: A History, Charleston, SC: The Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1999, pp.137-139.

- ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 9, pp. 273-286.

- Dean S. Thomas, An Introduction To Civil War Artillery. Arendtsville, PA: Thomas Publications, 1985, pp. 45 and 49-51.

- ORN, Ser.1, Vol. 9, pp. 272. 283, 291; and U.S. Congress, 3rd Session, Joint Committee Report On The Conduct Of The War, Vol. 4, Part 3, p. 335.

- ORN, Ser.1, Vol. 9, pp. 272. 283, 291; and U.S. Congress, 3rd Session, Joint Committee Report On The Conduct Of The War, Vol. 4, Part 3, p. 335.

29, ORN, Ser, 1, Vol. 4, p. 293; and Jeff Kincaid, Artillery: An Illustrated History Of Its Impact, Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2007, p.116.

- Branch, p. 145.

- Edwin Olmstead, William E. Stark, and Spencer Tucker, The Big Guns: Civil, Seacoast And Naval Cannon. Alexandria Bay, NY: 1997, pp. 177-178.

- New York Herald, May 4, 1862; and New York Times, May 5, 1862.

- ORN, Ser.1, Vol. 9, p.279; and Branch, pp. 146-147.

- ORN, Ser.1, Vol..9, pp. 287-290.

- Paul H.Silverstone, Civil War Navies, 1855-1883. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001, pp. 30, 53, 73, and 105.

- ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 7, p. 279.

- IBID, pp. 276 and 279-81.

- Branch, pp. 156-157.

- Trotter, pp. 144-145.

- ORN, Ser., 1, Vol. 9, pp. 274, 288, 290, and 294.