CSS Alabama, commanded by Captain Raphael Semmes, had spent nearly two years capturing and destroying 65 Northern merchant ships and whalers. There were seven different expeditionary raids from the Eastern Atlantic to the Java Sea and back near where the vessel had been built. The commerce raider had become legendary and captured the imagination of most of the world. Many, however, considered Semmes and his ship piratical and it had to be destroyed.

GOD HELPS THOSE THAT HELP THEMSELVES

The Alabama arrived off Cape Town, South Africa, in late July 1863 in a dramatic fashion. The cruiser captured the bark Sea Bride within sight of Cape Town. Semmes sold that merchantman and it’s cargo to a South African citizen. By September 24, 1863, Semmes set a course across the Indian Ocean, sinking several ships, reaching Singapore on December 21, 1863. There he viewed more than 20 Northern merchant ships rotting unemployed at anchor. He knew that his ship and the other Confederate commerce raiders had been very successful in disrupting US shipping.[1]

CATCH ME IF YOU CAN

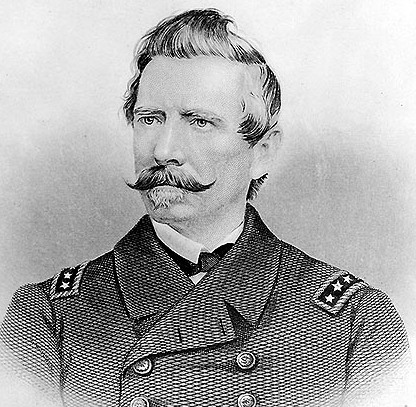

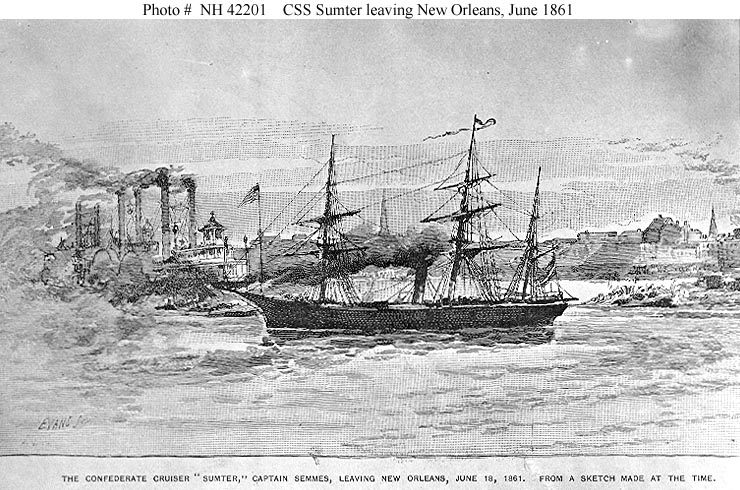

The US Navy tried to track down Alabama at sea. All Federal efforts to catch the Confederate cruiser failed. The USS Tuscarora, captained by Commander Tunis A. M. Craven, along with Kearsarge and Chippewa, had already trapped Semmes and CSS Sumter at Gibraltar. Semmes escaped and eventually took command of CSS Alabama. Craven was then given the duty of blocking the escape of Hull 290 (soon to be CSS Alabama) from Birkenhead., England. Craven, however, was unsuccessful.

A few weeks later, USS San Jacinto trapped Alabama and its supply ship Agrippina in the harbor of Port-de-France, Martinique. Even though the Federals set up picket boats with flares to observe any movement of the cruiser, Semmes used a heavy squall to escape. A flare was set off, and San Jacinto searched in vain for the Confederate raider. Semmes then rendezvoused with Agrippina near Blanquilla, Venezuela, and Alabama went on several other destructive cruises.[2]

When Semmes neared the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, the part paddler Vanderbilt tried to track the commerce raider down. The Vanderbilt was well-armed with two 100-pounder rifles. The two ships played a cat and mouse game until the commander of the paddler, Commander C.H. Baldwin,

decided that Alabama had gone into the Indian Ocean toward Mauritius. Semmes was still in South African waters and then sailed across the Indian Ocean. When Semmes reached the Strait of Sunda, he tried to duel USS Wyoming. The ships eluded each other. The Alabama returned to Cape Town in March 1864. Semmes realized that since his ship had been at sea for so long, he needed to return to Europe to drydock his ship. The Alabama reached Cherbourg, France, on June 11, 1864.[3]

WELCOME TO THE CONFEDERATE NAVY EUROPE

When Alabama arrived at Cherbourg, two other Confederate cruisers, CSS Georgia and CSS Rappahannock, were already trapped in French ports. The CSS Florida had recently escaped drydock to continue cruising the Atlantic, and two ironclad rams were secretly being built in Bordeaux by the Arman Brothers. Flag Officer Samuel Barron commanded these forces.

From Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, The Macmillan Company.

Barron had been a midshipman since he was two years old and had served with distinction throughout his career. He was captured during the Battle of Hatteras Inlet. He was detached to France. [4]His command included all the ships then docked in France as well as four ships then under construction. With James Bulloch’s help, Barron tried to create a Confederate navy capable of challenging the US Navy and breaking the blockade.[5]

Semmes reported to Barron that his ship desperately needed repairs and that he was ill. Lieutenant Arthur Sinclair noted that Alabama had cruised from the day, August 24, 1862, and during this time had visited two-thirds of the globe, experiencing all vicissitudes of climate and hardships attending constant cruising.” [6]

Semmes and Barron were assured by John Slidell, the Confederate Commissioner in France, that he did not think there would be a problem using a French dockyard for extensive repairs. He was incorrect in this assumption as the French denied the Confederates’ requests for anything but temporary repairs.[7]

TRAP IS LAID

U.S. Minister to France, William L. Drayton, immediately protested Alabama’s arrival in Cherbourg and planned use of French docking facilities by a vessel “so obnoxious and so notorious.” A telegram was sent to Captain John Ancrum Winslow, commander of USS Kearsarge, then at Flushing, The Netherlands, to take his ship to Cherbourg. Before setting sail, he sent telegrams for USS St. Louis and USS Niagara to come immediately to his assistance. There were still Confederate raiders located in French ports to blockade. Winslow needed supplies to maintain his station off the French coast as it was feared that CSS Rappahannock was planning to escape. [8]

SLOWLY CLOSING IN

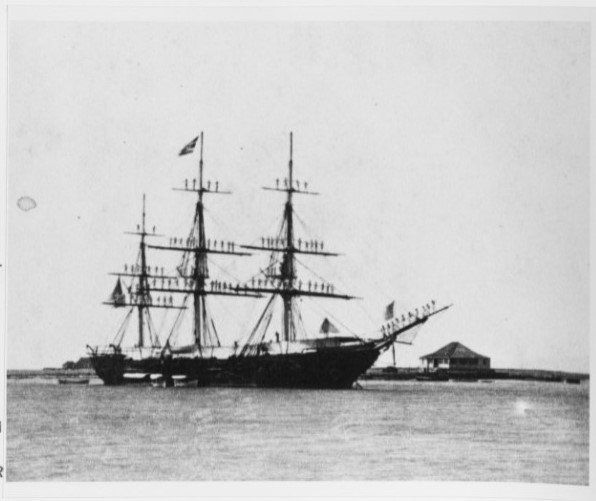

The sailing sloop of war St. Louis had been commissioned in 1828. It was armed with four VIII-inch shell guns, twelve 32-pounders, two 20-pounder rifles, and two-12-pounders.[9] The other vessel closing in was the steam screw frigate USS Niagara, built at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and commissioned in 1858. The Niagara mounted a main battery of twelve 150-pounder rifles and twenty XI-inch Dahlgrens. [10] These ships were en route to the French coast, and it was only a matter of time before they arrived. The Niagara alone could easily blow Alabama out of the water.

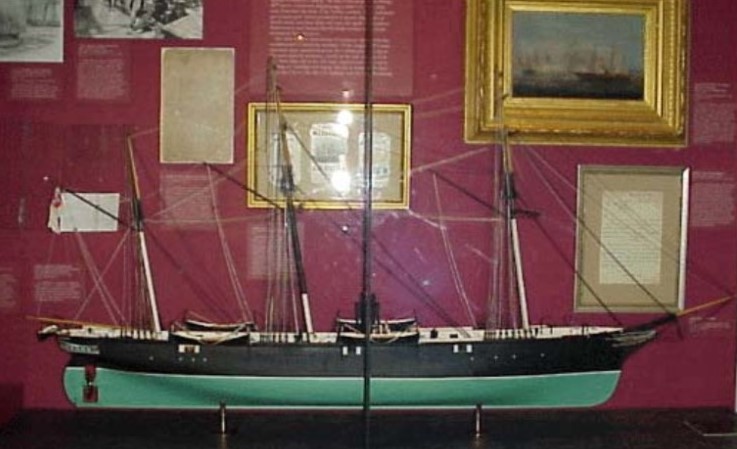

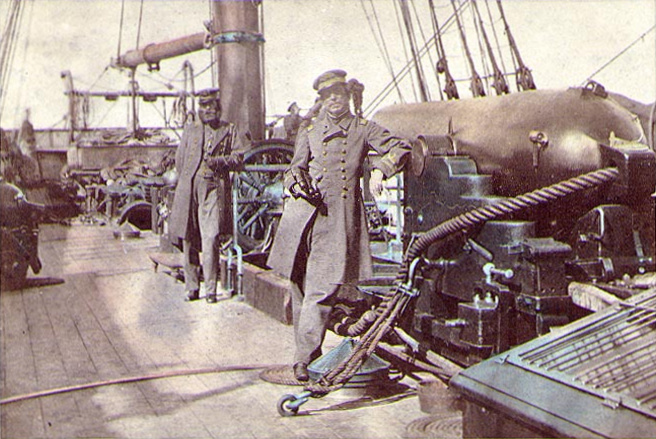

USS KEARSARGE

The Kearsarge was a product of the Union’s emergency to gunboat program. The sloop of war was bark rigged, and part of the two ship Mohican-class designed at the Portsmouth Navy Yard in Kittery, Maine. Commissioned on January 24, 1862, Kearsarge was detailed to the European Squadron with the duty to track down Confederate cruisers. Before steaming in June 1864 in the English Channel, Kearsarge had been searching the coast of Northern Europe, the Outer Hebrides, and Madeira for any Confederate cruiser.

While in the Azores, Captain John Winslow, then the new commander of the sloop of war, had Kearsarge given hull armor by hanging 720 feet of single-link iron chain in three courses up and down the sloop’s port and starboard midsection. This was done to protect its engine and boilers from enemy shot. Wooden planking, painted black to match the hull, covered the chain cladding (chain mail). A little more than a month before Kearsarge’s encounter with Alabama, the Union ship ran aground and secured repairs in a Dutch shipyard.[11]

USS KEARSARGE CHARACTERISTICS

TONNAGE: 1,550 tons

LENGTH: 196’6”

BEAM: 33’ 10”

DRAFT: 15’9”

MACHINERY: 1 screw, 2-cylinder horizontal back-acting engine, 2 boilers

SPEED: 11 knots

COMPLIMENT: 160 officers and men

ARMAMENT: two XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns, four 32-pounder shell guns, one 30-pounder rifle, and one 12-pounder smoothbore.[12]

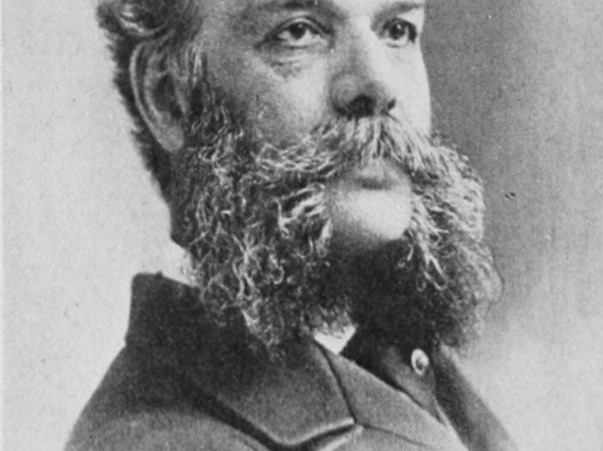

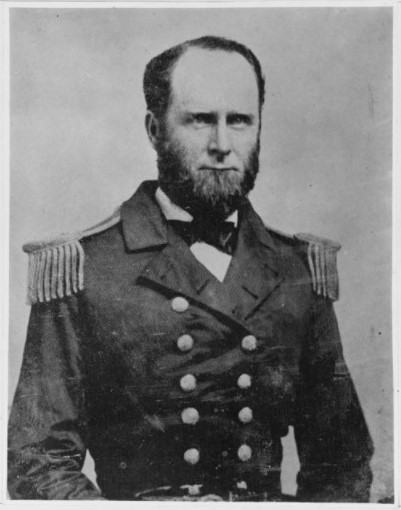

THE MAN WHO SANK CSS ALABAMA

John Ancrum Winslow was a Mayflower descendant. Although he was born in Wilmington, North Carolina, he became a staunch Unionist and fervent abolitionist. Winslow joined the US Navy as a midshipman in 1827. He served during the Mexican War with distinction. Lt. Winslow was commended for gallantry in action by Commodore Matthew C. Perry. He served with Rafael Semmes on USS Cumberland. When the war commenced, he commanded the 2nd Lighthouse District. First assigned to the Western Gunboat Flotilla on Mississippi, he contracted malaria and returned. He had adequately recovered from this disease to assume command of USS Kearsarge.

PREPARATIONS FOR BATTLE

The Kearsarge arrived off Cherbourg on June 14, 1864. Semmes advised Flag Officer Barron two days later: “that the position of Alabama here has somewhat changed since I wrote to you. The enemy’s steamer, the Kearsarge, having appeared off this port, and being heavier, if any, in her armament than myself, I have deemed it my duty to go out and engage her.” [13] Semmes knew that soon other Union warships would arrive off Cherbourg making it impossible to escape.

The Alabama’s commander discussed with his executive officer, Lieutenant John M. Kell, his desire to strike at Kearsarge. Kell noted that the ships were of similar strength. The executive officer also knew that the weight of the Union battery was heavier, 430 lbs. of shot to Alabama’s 360 lbs. The major issue was that after two years of cruising, Alabama’s gunpowder and explosive shells may have deteriorated.[14]

Two alternatives faced Semmes. He could try to slip past Kearsarge in a daring dark night dash; however, the odds were not in his favor to make this attempt. He could put the ship into dry dock, pay off the crew, and let the cruiser rot away in Cherbourg. This would be an inglorious end to the ship and simply not equal to all of the cruiser’s success over the past two years. The Alabama’s commander was a fighter, as seen in his sinking of USS Hatteras and his desire to take on USS Wyoming. Semmes wanted to prove that Alabama was truly a ship of war and not a pirate, and he could only do so by challenging Winslow to a duel. [15]

THROW DOWN THE GAUNTLET

Accordingly, a challenge was sent through diplomatic channels to Capt. Winslow stating that “my intention is to fight the Kearsarge as soon as I can make the necessary arrangements. I hope that these will not detain more than to-morrow or the morrow morning at the farthest. I beg she will not depart until I am ready to go out. I have the honor to be Your obedient servant, R. Semmes, Captain.” [16]

Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 57256.

WITNESSES GATHER

Sunday, June 19, 1864, dawned clear without a cloud in the sky. Hundreds upon hundreds of people came from Paris and elsewhere knowing that a historic battle would soon be fought before them, and they wished to witness history in the making.

John Lancaster, owner of the steam yacht Deerhound, offered his children the opportunity to go to church or to view the battle…they chose the battle. Other smaller boats and various French vessels accompanied Alabama during its voyage out of Cherbourg harbor. Artist Edouard Manet was on one of those boats to paint the battle. As Alabama steamed past the French ship of the line Napoleon, that ship’s band played ‘Dixie’ to encourage Alabama on to its destiny. The French broadside ironclad, Couronne, escorted the Confederate cruise out past the three-mile limit.[17]

A poet on Alabama wrote as his ship steamed toward battle:

“We’re homeward, we’re homeward bound

And soon we shall stand on English ground.

But ere that English land we see,

We first must fight the Kearsargee.”[18]

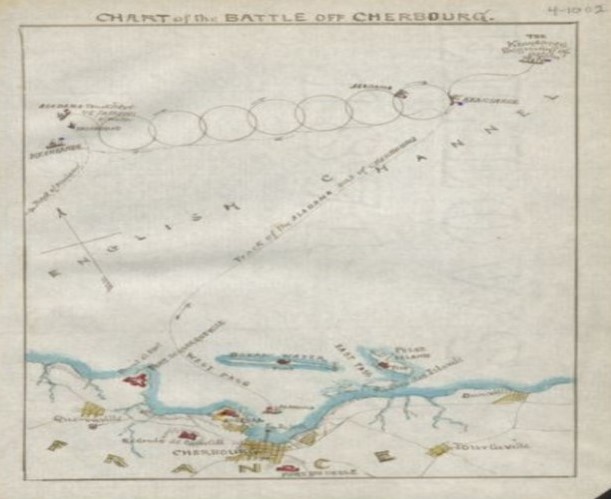

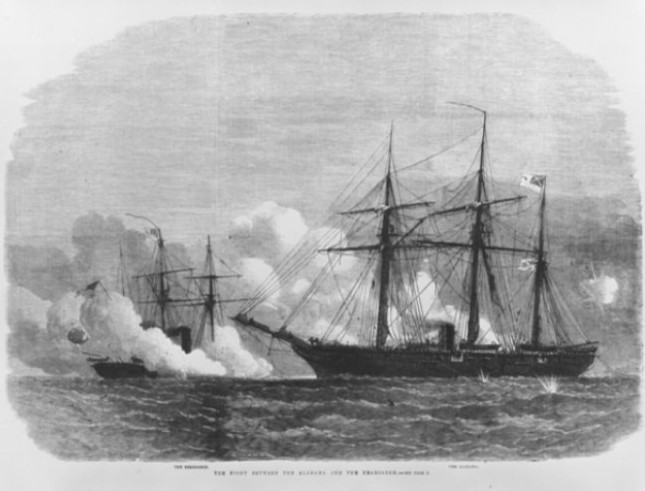

THE BATTLE IS JOINED

The Kearsarge waited for seven miles off the coast to ensure the fight was not in French territorial waters. Semmes opened fire first with his starboard broadside. The shots were high and missed their target. Winslow tried to close with Alabama; however, slipped away from a close ship-to-ship action. The two warships then faced each other with their starboard batteries. They began to steam in concentric, spiraling circles moving southwest. Each ship was striving to cross in front of the bow of its enemy to deliver a deadly raking shot. Neither warship could achieve that goal. [19]

GUNNERY WINS THE DAY

Engraver unknown. The Mariners’ Museum # ARI178791.

When Kearsarge opened fire at about 900 yards, the shells had an immediate effect on Alabama. The Kearsarge’s men appeared to be better trained and far more deliberate with their aim. The result was that Alabama soon felt the impact of Kearsarge but inflicted no real damage. The gunfire by now had gotten very hot, and many Confederate sailors were strewn about the deck dead, dying, or badly wounded. “After the lapse of about one hour and ten minutes,” Semmes recalled, “our ship was deemed to be in a sinking condition, the enemy’s shells having exploded in our side, and between decks, opening large apertures through which the water rushed with great rapidity.” [20]

THE ALABAMA IS NO MORE

Semmes tried to save his ship by running it toward the French coast. Yet, there was nothing he could do as Alabama was rapidly sinking by the stern, and the boiler fires had been extinguished by the rising water. Captain Semmes lowered the cruiser’s flag and sent a boat to Kearsarge for assistance. The Alabama’s bow then rose straight up into the air and vanished beneath the English Channel. [21]

RESCUE AMIDST CONTROVERSY

Semmes stated that when he lowered Alabama’s flag and sent a boat to Kearsarge requesting help, Winslow’s ship continued to send shots into the sinking commerce raider from a four hundred yard distance. Semmes noted with disdain that “Kearsarge fired upon me five times after my colors had been struck. It is charitable to suppose that a ship of a Christian nation could not have done this intentionally.”[22] “When the object was apparent, the Kearsarge was steered across the bow of the Alabama for a raking fire; but, before reaching this point, Alabama struck.” Winslow reported and added, “Uncertain whether Captain Semmes was not using some ruse, the Kearsarge stopped.”

A boat from Alabama then came alongside the Union sloop, asking for help for the floundering Confederate seamen. Several French boats, as well as boats from Kearsarge, picked survivors to become POWs. One French pilot rescued six men and returned them to Cherbourg. Winslow asked Deerhound to help, and the steam yacht became very active, picking up survivors.

The Deerhound collected 40 officers and crew of Alabama, including Raphael Semmes. John Lancaster delivered them to Southampton. Winslow was engaged by this action, writing: “I could not believe that the commander of that vessel could be guilty of so disgraceful an act as taking prisoners off.” [23] Winslow could not do anything about Deerhound’s actions.

CHAIN MAIL

Semmes was surprised to watch many shells strike the Kearsarge, which inflicted no damage. Winslow’s addition of this disguised armor played a decisive role in his ship’s victory. Raphael Semmes was incensed by his enemy’s chain mail. “This was discovered…that her midship section, on both sides, was thoroughly iron-coated; this having been done with chains, constructed for the purpose, placed perpendicularly, from the rail to the water’s edge. The chain mail was covered by thin outer planking, which gave no indication of the armor beneath. This planking had been ripped off, in every direction, by our shot and she was effectually guarded; however, in this section from penetration.”[24] Semmes noted that had he known that Kearsarge was virtually an ironclad, he would not have challenged the Federal warship to a duel.

BAD POWDER

The Confederates opened fire first and eventually fired 370 rounds; yet, only struck Kearsarge 28 times. Most of the shot and shell overshot the Federal sloop. One 32-pounder shell struck the starboard gangway, which cut part of the anchor chain. A few other 32-pounder shots hit Kearsarge and exploded, breaking part of the chain armor. These shots hit above the water and would not have done serious damage to the Union ship. Many shots went through the rigging while others went through the smokestack, hit the top of the engine house, and one shell exploded, injuring three crew members. [25] One 110-pounder Blakeley shell drove into Kearsarge’s stern post; yet, failed to explode. John M. McKenzie of Alabama’s crew knew that if that shell “had exploded, the Kearsarge would have gone to the bottom instead of the Alabama. But our ammunition was old and had lost its strength.” [26]

Semmes believed that his powder and fuses were faulty after being so long at sea. He wrote Samuel Barron, “Unfortunately, my magazine had been placed near the condensing apparatus with which we generated fresh water for the crew, and it was in consequence frequently filled with steam. We were obliged to air it very frequently to keep it all dry. Before my arrival at Cherbourg all powder which I had in barrels was so damaged that I was compelled to throw it overboard. I had a good supply, however, put up in cartridges and stowed in copper tanks, and this did not show any signs of deterioration. I concluded that it must be good. I am now convinced from the want of penetrating power of my shot and shells….Well, it is the fortune of war.” [27]

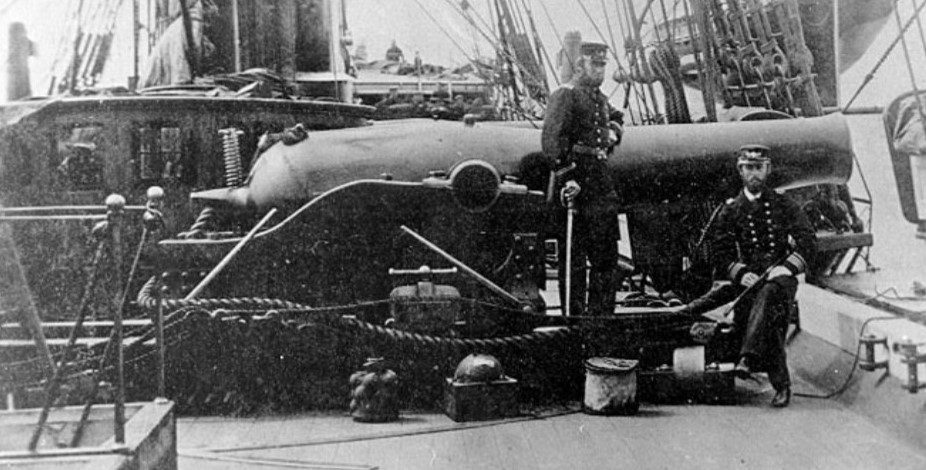

DELIBERATE AIM WINS THE DAY

When Winslow’s sloop opened fire at about 900 yards, it immediately appeared that Kearsarge’s gunnery had a deadly impact on Alabama. The shell fire became rather hot. The two XI-inch Dahlgren’s inflicted the most damage to the Confederate cruiser. One member of a Dahlgren gun crew, Ordinary Seaman William Gowin, became overly excited during the action. His crewmates cheered at every successful shot they sent into Alabama. Gowin then would wave his hand over his head, shouting: “Victory is ours!” [28]

LAURELS EVERYWHERE

The Kearsarge fired 173 shot and shell, according to Gunner Franklin A. Graham, at Alabama. The gun crews fired with great precision and discipline. After the battle, Winslow praised the officers and crew with particular notice given to the gun crews. One African American, Seaman Joachim Pease, was the loader of gun No. 2 and was given great notice for his service. He would receive the Medal of Honor for his devoted and determined duty on June 19, 1864. Pease’s citation reads: “Acting as loader…during this bitter engagement Pease exhibited marked coolness and good conduct and was highly recommended…for gallantry under fire.” [29]

The Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wrote Winslow: “I congratulate you for your good fortune in meeting the Alabama, which so long avoided the fastest ship’s of the service…for the ability displayed in the contest you have the thanks of the department,…The battle was so brief, the victory so decisive, and the comparative results so striking will be reminded of the brilliant actions of our infant Navy, which have been repeated and illustrated in this engagement…Our countrymen have reason to be satisfied that in this, as in every naval action of this unhappy war, neither the ship’s, the guns, nor the crews have deteriorated, but that they maintain the ability and continue the renown which have ever adorned our naval annals.” Besides this laudatory message, Winslow also received a vote of thanks from Congress and was promoted to Commodore with his commission dated June 19, 1864. [30]

The news of the sinking of Alabama was greeted with great jubilation throughout the North. The Alabama had finally found its way to Davy Jones’s locker, and the seas would soon again be safe for American shipping.

A TEAR FOR THOSE WHO PERISHED

The USS Kearsarge suffered just three wounded during this engagement: James Macbeth, John Dempsey, and William Gowin. Dempsey had his right arm amputated. Ordinary Seaman Gowin died from his wounds. Surgeon John M. Brown noted Gowin’s last words: “Its all right and I am satisfied for we are whipping the Alabama,” Gowin said, “I am willingly lose a leg or life if it is necessary.”[31]

The Confederate cruiser suffered nine killed, 10 drowned, and 21 wounded. Semmes was painfully wounded in the hand. Two of the drowned crew members were Ship’s Boy David Henry White and Fireman Andrew Shilland. Both were listed as ‘colored slaves’ on Alabama’s muster roll. It is ironic that two enslaved slaves fighting for the South against the North should have died in European waters less than ten months before their freedom was assured. Another drowning victim was Dr. David Herbert Llewellyn. He heroically gave up his seat in one of Alabama’s cutters, even though he could not swim.[32]

ENDNOTES

- Raimondo Luraghi, A History Of The Confederate Navy, Annapolis, MD.: Naval Institute Press, 1996, p.231.

- Bern Anderson, By Sea And By River: The Naval History Of The Civil War, New York: Da Capo Press, 1989, pp. 204-205.

- IBID, p. 207.

- Patricia Faust, Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Civil War, New York: Harper Perennial, 1996, pp. 41-42.

- Warren F. Spencer, The Confederate Navy In Europe, Tuscaloosa, AL.: The University of Alabama Press, 1983, pp. 183-186.

- Navy History Division, Navy Department, Civil War Naval Chronology 1861-1865, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1971, vol, 4, p. 72.

- Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Navies In The War Of The Rebellion ( hereinafter referred to as ORN), Washington: Government Printing Office, ser. 1, vol. 3, p. 58.

- IBID, p. 52.

- Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies 1855-1883, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, p. 98.

- IBID, p. 17

- ORN, ser. 1, vol 3, p. 649.

- Silverstone, pp. 22-23.

- Civil War Naval Chronology, v 4, p. 74.

- John McIntosh Kell, Recollections Of A Naval Life Including The Cruises Of The Confederate States Steamers “Sumter” And “Alabama,” Washington: Neale Co., 1900, p. 245; and J. Thomas Scharf, History Of The Confederate States Navy, New York: Gramercy Books, p. 799; and ORN, ser. 1, vol. 3, p. 648.

- Spencer, pp. 186-187.

- Semmes, Memoirs, pp. 751-752.

- Luraghi, p. 319.

- Civil War Naval Chronology, V. 4, p. 74.

- ORN, ser.1, vol. 3, p. 56.

- Civil War Naval Chronology, vol. 4, p. 78.

- Scharf, p. 800.

- IBID.

- ORN, ser. 1, vol. 3, p. 61.

- Scharf, p. 800.

- ORN, ser. 1, vol. 3, p.63.

- Civil War Naval Chronology, V 4, p. 74.

- ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 3, p. 664.

- IBID.,p. 70

- Charles H. Hanna, African American Recipients Of The Medal Of Honor: A Biographical Dictionary, Civil War To Vietnam. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2002, p. 19.

- Civil War Naval Chronology, V 4, p. 78.

- ORN, ser. 1, vol. 3, pp. 69-70.

- Spencer, p. 189.

NOTE: Please refer to my blogs, SINKING OF USS HATTERAS and RAPHAEL SEMMES AND CSS SUMTER, for more information about Captain Raphael Semmes and CSS ALABAMA’s cruises.