There was no formal naval intelligence system established during the American Civil War. While a few examples exist of Northern sympathizers, free Blacks, like Mary Louvestre of Portsmouth, sent messages to various Union commanders about the Confederate ironclad construction effort. These links were unofficial and were generally between one Union officer and an individual. The Union nor the Confederacy needed to rely on such clandestine methods since Northern and Southern newspapers provided ample information, usually in a boastful manner. Each antagonist simply needed to obtain a copy of The New York Times or Mobile Register to gather all they needed to know about ironclad development.

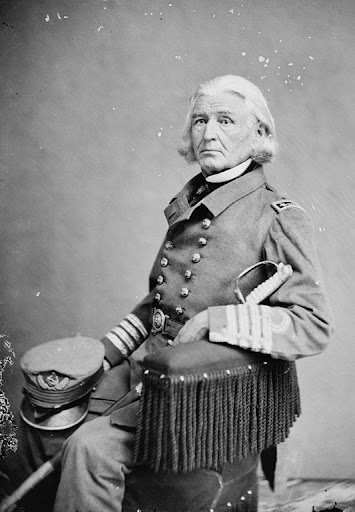

Union intelligence was able to receive valuable knowledge about the construction and impending attack of CSS Virginia. The information appeared to flow back and forth across Hampton Roads. On October 6, 1861, Major General John Ellis Wool, stationed at Fort Monroe as commander of the Union Department of Virginia, wrote to Lieutenant General Winfield Scott:

“I also mentioned to you that Newport News was threatened by the Confederates in order to aid in getting to sea two steamers in James River, and also the Merrimac at Norfolk. This ship is constructed to resist cannon shot. I have this morning seen the flag-officer in the Roads, who more than confirms all that I have said on the subject, and that it is settled that an attempt will be very soon made to get these vessels to sea. In order to facilitate this movement an attempt will be made to get possession of Newport News. We have guns, but not artillerists sufficient to man them, at Newport News; I hope you will at once send back the four companies of artillery recently sent to Washington. If you do not send these, or some other companies of artillery to supply their places, I trust you will not hold me responsible for any disaster that may befall us at Newport News. The danger, I assure you, is imminent. This subject I presented to the President in Cabinet council, when I assured them of the intentions of the rebels, and that it was their design to attack Newport News, and, as it was reported, very soon. The flag-officer is satisfied that such will be the case. He says there is no mistake as to their capturing Newport News and that the steamers may get to sea. He also said the Merrimac is so constructed that no cannon shot can make an impression upon her. “

Wool would continue to receive conflicting messages over the next six months, which prompted the general to often send dire reports of impending doom to Washington, as did other officers. Flag officer Louis M. Goldsborough, commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, bombarded the naval secretary Gideon Welles with news about the Confederate ironclad. On October 17, 1861, Goldsborough noted, “I have received minute reliable information with regard to the preparation of the Merrimack for an attack on Newport News … I am quite satisfied that unless her stability be compromised by her heavy top works of wood and iron and her weight of batteries, she will in all probability, prove to be exceedingly formidable.”

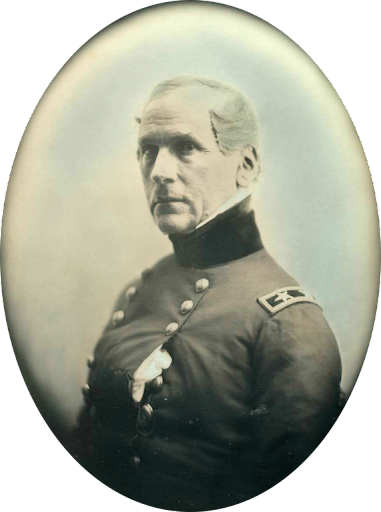

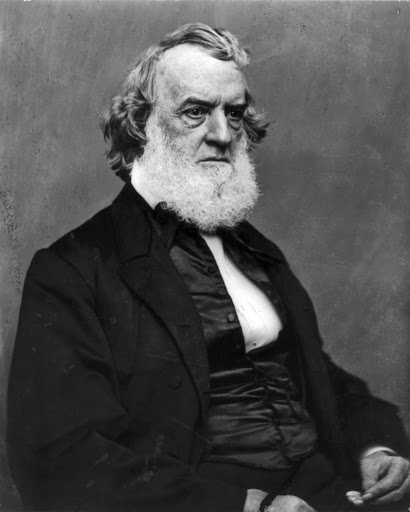

Mathew Brady, photographer.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Southern printed media continually boasted about the power of its new ironclad, but there were problems, as The Mobile Register proclaimed:

“It would seem that the hull of the Merrimac is being converted into an iron-cased battery. If so, she would be a floating fortress that will be able to defeat the whole Navy of the United States and bomb its cities. Her great size, strength, and powerful engines and speed, combined with the invulnerability secured by the iron casting, will make the dispersal or the destruction of the blockading fleet an easy task for her. Her immense tonnage will enable her to carry an armor proof against any projectile and she could entertain herself by throwing bombs into Fortress Monroe, even without risk. We hope soon to hear that she is ready to commence her avenging career on the seas.”

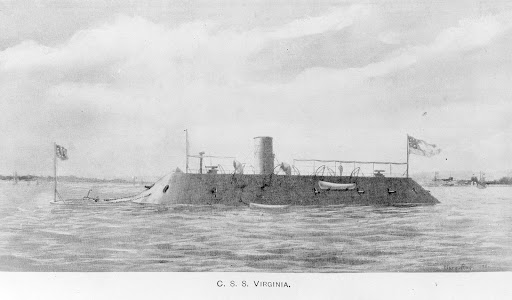

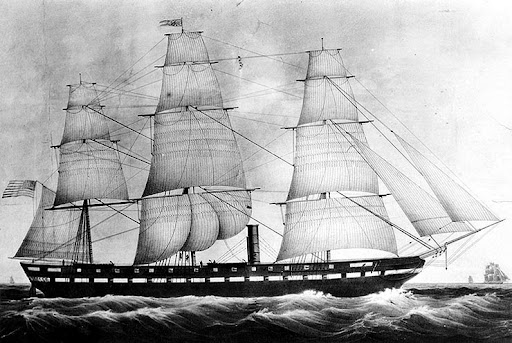

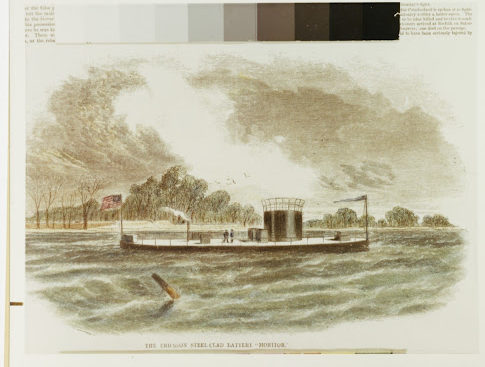

Lithograph after drawing by G. G. Pook.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 46248.

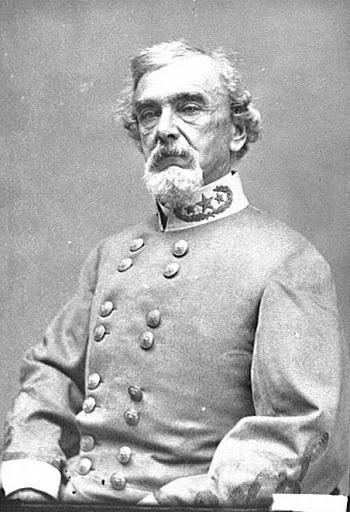

Confederate naval leaders were concerned about how the public interpreted such articles and whether they considered them written to boost public confidence in the Confederate navy and its conversion project at Gosport Navy Yard. “The Mobile Register contains information in relation to the Merrimac of much value to the enemy,” Lieutenant John Mercer Brooke, the designer of the ironclad conversion project, wrote in his diary, “Editors are doing infinite harm in that way. I shall begin to think that even the South cannot tolerate a free press.” Brooke was also concerned that Southerners, their expectations heightened by a boastful press, would expect too much of the ironclad. He was somewhat relieved when the Norfolk Day Book announced the failure of the iron plate tests on Jamestown Island but still feared that the Federals would begin building their own armorclads to counter news of the Confederate ironclad.

Southern newspapers continued their coverage of Merrimac’s conversion. J. Nicholson was allowed to go aboard and survey the ironclad in dry dock and provided a thorough review detailing the vessel’s progress and capabilities in the Lynchburg Virginian:

“To get into it would be impossible, and to make a hole in it would be impossible, and to make a hole in it with anything or machinery just the same. It will be covered with oak plank, two courses, each four inches thick, and then encased in railroad iron.”

Flag Officer French Forrest, a hero of the War of 1812 and commandant of the Gosport Navy Yard, was so enraged by this latest series of articles about the conversion project that he ordered Gosport’s gates closed to all visitors. Workers were ordered to sign in and out of the yard. Failure to do so would result in the loss of a day’s wages. Forrest could only redouble his security around the ironclad. On December 7, 1861, Captain Reuben Thom’s Company C, CS Marine Corps, arrived at Gosport Navy Yard. Thom detached Marines to various gunboats, such as CSS Jamestown and the receiving ship CSS Confederate States (formerly USF United States) as guards. He retained 54 men to act as sentries for the ironclad.

Department of Norfolk commander Benjamin Huger saw spies and malcontents everywhere. He wrote to Richmond: “My object is to get rid of a disaffected and troublesome population, most of whom are idle and would be liable to turn against us if we were in any danger of defeat.” Huger suggested that martial law might even be necessary to control the local population.

Major William Norris, CS Signal Corps, and former Baltimore lawyer had been originally assigned in October 1861 to Major General John Bankhead Magruder’s Army of the Peninsula to develop a signal system between the Peninsula and Southside Hampton Roads. Norris had an even more important duty to perform in Norfolk as he was also chief of the Confederate Secret Service Bureau. It is not known how much Norris learned from Federal deserters; nevertheless, he kept a vigilant watch over shipbuilding activities at Gosport Navy Yard.

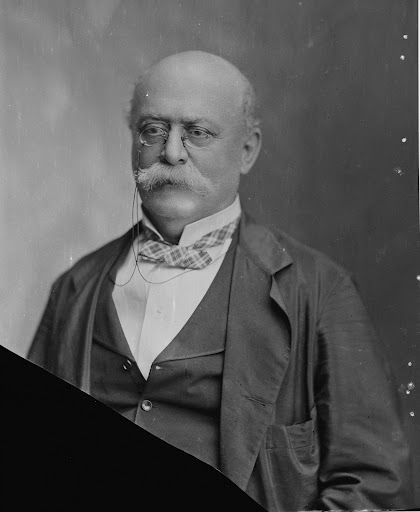

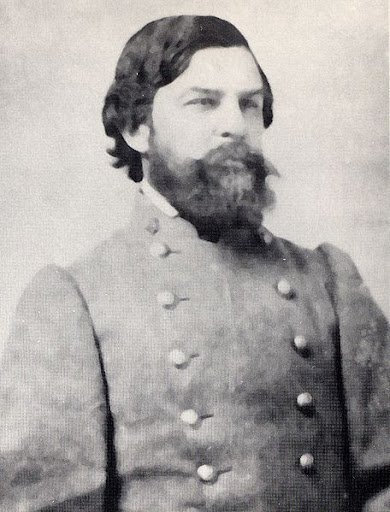

Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Center of Military History,

United States Army. Public domain.

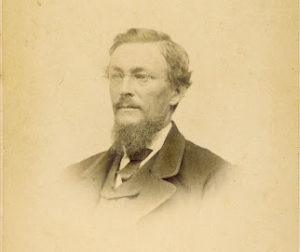

One of the individuals who slipped through Norris’s hands was the former enslaved Mary Louvestre. Mary (or Marie) was a seamstress in Portsmouth and had gathered information from Northern sympathizers working on the CSS Virginia conversion project. Using a ruse, Louvestre (spelled Touvestre in some documents) obtained a pass and then found her way to Washington, D.C., to meet with Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. Welles later recounted that she “told me the condition of the vessel, and took from her clothing a paper written by a mechanic working on the ‘Merrimac,’ describing the nature of the work, its progress, and probable completion.”

The Confederates became extremely worried about security. Information leaked almost daily to the Federals across Hampton Roads. Escaped enslaved persons exchanged prisoners of war, and Northern sympathizers and other informants supplied the Federals with up-to-date information about the Confederate ironclad project. The City of Portsmouth established a patrol boat system to stop enslaved persons from reaching Union lines with information about the ironclad. The patrol soon uncovered another espionage technique. Sympathizers or spies sent corked bottles containing secret messages via the Elizabeth River’s outgoing tide toward Fort Monroe.

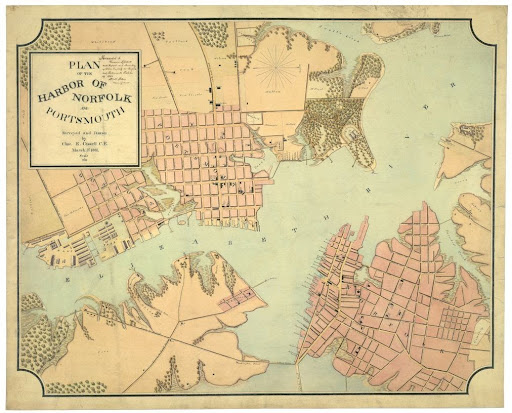

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Despite the censorship, guards, and threats of martial law, the leaks continued. Simultaneous with the ironclad’s first float test, an article appeared in The New York Times commenting that the “work on the Merrimac was stopped on Saturday last, and she is now at the Navy Yard, drawing so much water that she could not get out even if she was ready for sea.” Since Norfolk was an exchange point for prisoners of war and civilians traveling north and south, the flow of information could not be stopped. Colonel LeGrand B. Cannon, General Wool’s chief of staff, remembered how one message from a Unionist workman in Gosport Navy Yard was delivered sewn inside the lining of an accomplice’s jacket. The message stated that the Confederate ironclad would soon attack Congress and Cumberland at Newport News Point. Cannon rushed the vital knowledge to Washington, D.C. Lincoln reportedly introduced the information at a cabinet meeting, which prompted Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Vasa Fox to quip, “Mr. President, you need not give yourself any trouble whatever about that vessel.”

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command

# NH 91990

Fox was confident because USS Monitor was nearing completion. The Union command was ready for the ironclad to see service. “Hurry her for sea,” Fox wrote to the ironclad’s designer, John Ericsson, “as the Merrimac is nearly ready at Norfolk and we wish to send her there.” The Confederate ironclad was still under construction. Welles believed that Monitor could easily steam up the Elizabeth River past the Confederate batteries and destroy the Merrimac as it sat in dry dock.

The Confederates were well aware of the Federal efforts to build several ironclads in East Coast shipyards. Northern publications were as indiscreet as Southern ones. On August 3, 1861, Northern newspapers blared that the U.S. Congress had appropriated $1.5 million for ironclad ship construction. The New York Times went on to note that Gideon Welles was authorized to “appoint a board of three skillful officers to investigate the plans and specifications that may be submitted for the construction or completion of iron or steel-clad steamships or steam batteries.

On August 7, 1861, every Northern port city newspaper included advertisements soliciting seagoing ironclad designs. The New York Times announced news about Monitor on January 30, followed on February 4 with a feature article. On March 6, 1862, the newspaper even announced that the Union ironclad had left New York and was headed south. Acting Assistant Paymaster William Keeler constantly escorted dignitaries, curiosity seekers, and the media on tours. He believed the little ironclad epitomized the strengths of American industry and thus fired an intense interest amongst the public.

Keeler even gave the editor of the Scientific American an extensive tour and presented plans of USS Monitor and other construction details to him, which were published. Lt. John Mercer Brooke’s summertime fears had come true. Once the Federals learned about the Merrimack conversion project, they turned the superior Northern industrial power to constructing ironclads. Brooke could only hope that the Confederate head start would be sufficient to attain naval superiority and break the blockade.

Since there was no censorship in the North, Norris utilized a series of Southern sympathizers and spies in New York City, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. Consequently, newspapers were sent south via telegram, US mail, and hand-delivered written coded messages. This vital information was freely passed through the lines via what William Norris called “the government route.” The Confederates were just as informed about the Union’s ironclads as the North was aware of the South’s armorclads. Yet, neither side was certain as to when either ironclad would strike.

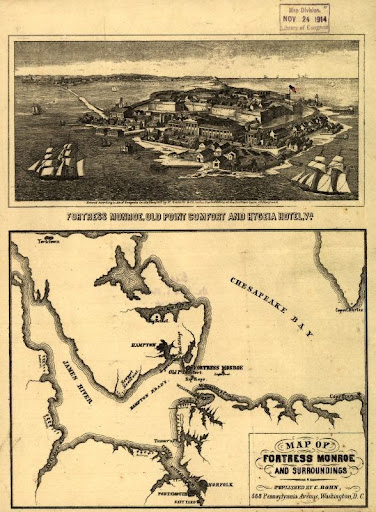

Hampton Roads was a natural amphitheater of the impending battle. The Federals maintained the northern shore even though the Confederates controlled the Southside with such major fortifications as Sewell’s Point, Craney Island, and Pig Point. Camp Butler at Newport News Point effectively sealed off the entrance to the James River. Fort Monroe and its companion work, Fort Calhoun on the Rip Raps, provided powerful gatekeepers at Hampton Roads’ outlet to the Chesapeake Bay.

Accordingly, Captain John Marston was captain of USS Roanoke and station commander in Hampton Roads during Goldsborough’s absence. He placed his capital ships to help seal off Hampton Roads in conjunction with these fortifications. If the Confederate ironclad sought to reach the Chesapeake Bay, Minnesota, Roanoke, and St. Lawrence were anchored just off Old Point Comfort. The Congress and Cumberland were moored off Newport News Point, blocking any move of the ironclad to Richmond. Two armed tugs, Dragon and Zouave, were positioned to tow these sailing ships at Newport News Point into action if needed.

Captain Marston noted the Federal fleet was patiently waiting for the Confederate ironclad: “I am anxiously expecting her and believe I am ready.” “Rumor of her expected appearance came so often,” recalled Thomas O. Selfridge of Cumberland, “that at last, it became a standing joke with the ship’s company.” Marston wrote to Gideon Welles on February 21, 1862, that “by a dispatch from General Wool, I learn that the Merrimac will positively attack Newport News within five days, acting in conjunction with the Jamestown and Yorktown from the James River, and that attack will be at night.”

The crewmen were ready for “a chance for active operations.” They had been on alert throughout the winter. They drilled “until every man knew not only the duties of his own station at quarters, but those of every station as well,” remembered Master Moses S. Stuyvesant of Cumberland. Captain Gershom Jacques Van Brunt, commander of USS Minnesota, summed up his frustration awaiting the Confederate ironclad when he wrote to Goldsborough, “We have nothing new here; all is quiet. The Merrimac is still invisible to us, but the report says she is ready to come out. I sincerely wish she would; I am quite tired of hearing of her.” Van Brunt added, “The sooner she gives us the opportunity to test the strength the better.” Nevertheless, the Confederate ironclad still did not appear.

As each day in March passed, the Union feared the impending attack of the Confederate ironclad. “She will be almost certain to commit great depredations to our armed and unarmed vessels in Hampton Roads,” wrote steam ram expert Lieutenant Colonel Charles Ellet. Goldsborough longed for Monitor to arrive in Hampton Roads as a counter to the Confederate ironclad. “I ask therefore if it would not be well to send the Ericsson,” he wrote Welles, “to contend with the vessel on her own terms. I hope the Dept. will be able to send the Ericsson soon to Hampton Roads to grapple with the Merrimac and lay her out as cold as a wedge.” Union intelligence was excellent, despite the efforts of Huger, Forrest, and Norris to plug information leaks.

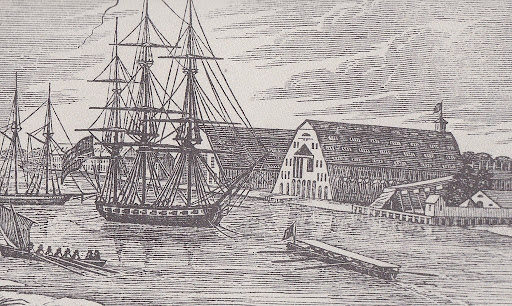

Harper’s Weekly, 22 March 1862.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 76324-KN

Welles had originally ordered Monitor to proceed to Hampton Roads. However, on March 6, as the Union ironclad left New York, he altered his plans to combat the Confederate ironclad and directed Monitor to steam directly to Washington, D.C. On March 7, 1862, he ordered Marston to send St. Lawrence, Cumberland, and Congress to the Potomac River. The Union Secretary of War’s new orders would leave only steamships in Hampton Roads. Either Welles had succumbed to McClellan’s request to silence the Confederate batteries blocking the Potomac River, or he had learned of Mallory’s orders that Virginia strike at Washington. Regardless of his motivations, the Union command was deeply concerned with what the Confederate ironclad might do whenever it ventured forth from the Elizabeth River. On March 8, 1862, they would certainly learn about the power of iron over wood and how naval warfare would be changed forevermore.

Note:

The Confederate ironclad that fought in Hampton Roads was originally the steam screw frigate USS Merrimack. The frigate was scuttled when the Federals abandoned it, and the Confederates then raised it. They converted the ship into an ironclad and christened the ship as CSS Virginia. Nevertheless, the Union would continue to call the Confederate ironclad Merrimack or incorrectly spelling it Merrimac.

Sources:

Quarstein, John V. The CSS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender, Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012.

———————— The Monitor Boys, Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011.