“When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field, or whatever. Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you.”

– Claude Monet

The View from Afar

A delicate breeze gently tousles the branches of trees that we cannot see at the shore. They cast shadows that dance – intertwining with the dappled golden light that illuminates this scene.

From afar, this work is peacefully composed, broken up into thirds both horizontally and vertically with the subject centered on the canvas. We’re watching a fisherman catching small herring with a long round dip net as he stands in his wooden boat. The fish glint and glimmer in the sun, drips of water cascade from the net catching the beams and becoming droplets of liquid light that twinkle in the water. It’s pastoral, quaint, and illustrative of coastal Massachusetts in 1912.

A Closer Look

But what our eyes and minds understand – at a distance- as literal, changes with each approaching step we take. What was the solid form of a fisherman in his boat, dissolves into thousands and thousands of fractals of light and color.

The boat that read as tan transforms into a spectrum of yellow, green, pink, red, blue, and many more tones and hues in between. The smooth edges, once defined, become broken dabs of paint quickly and thickly applied with a palette knife.

This thick application of paint is called “impasto”. It’s a technique, widely used across many art styles since the 17th century. It adds texture and dimension to the canvas and is also a well known aspect of Impressionist art.

Chasing an Impression

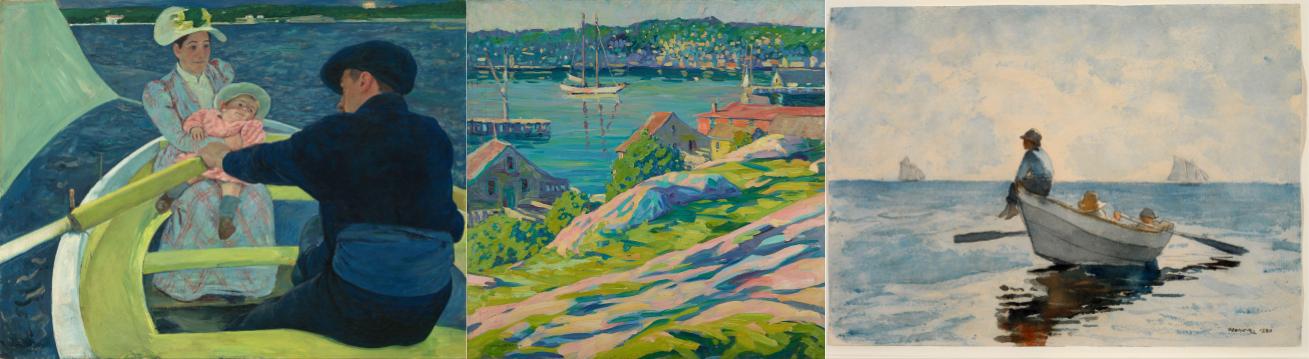

The artist of this work, Philip Little, is known as one of the American Impressionists – a group that also includes artists such as Mary Cassat, Winslow Homer, and Jane Peterson. (You might recognize that name – Jane Peterson from the Beyond the Frame episode “Uniquely Jane”)

These artists mainly gathered in coastal New England areas, painting local scenery and everyday life outdoors, “en plein air”. Their focus was to seek changing light and color just as their revolutionary founders had done in France nearly 50 years before this work was painted.

The Movement that Changed Art

In the late 19th and early 20th century, technology began changing rapidly and photography was on the rise – allowing the mechanical capture of the world as it is. And as a reaction to the new technology and as an act of rebellion against the traditional standards, lofty subjects, and almost photographic correctness of Realist and Romantic painting, the group that would become known as the Impressionists did something that had never been done before.

They became less focused on painting a scene exactly as it looked in person and instead, found new techniques to explore the visual mixing of color, and to express light and movement. They sought ways to portray the aesthetic of the moment – the way it felt to experience it. Something that changed the course of art forever.

The Pull of the Water

For many Impressionists, the water proved to be both a challenge and an ever-changing source of inspiration (I’ve got a soapbox blog in the works – check back soon to read that one!) and so they tended to gather in painting colonies in coastal towns – sharing new ideas and painting in new ways. Philip Little was drawn too.

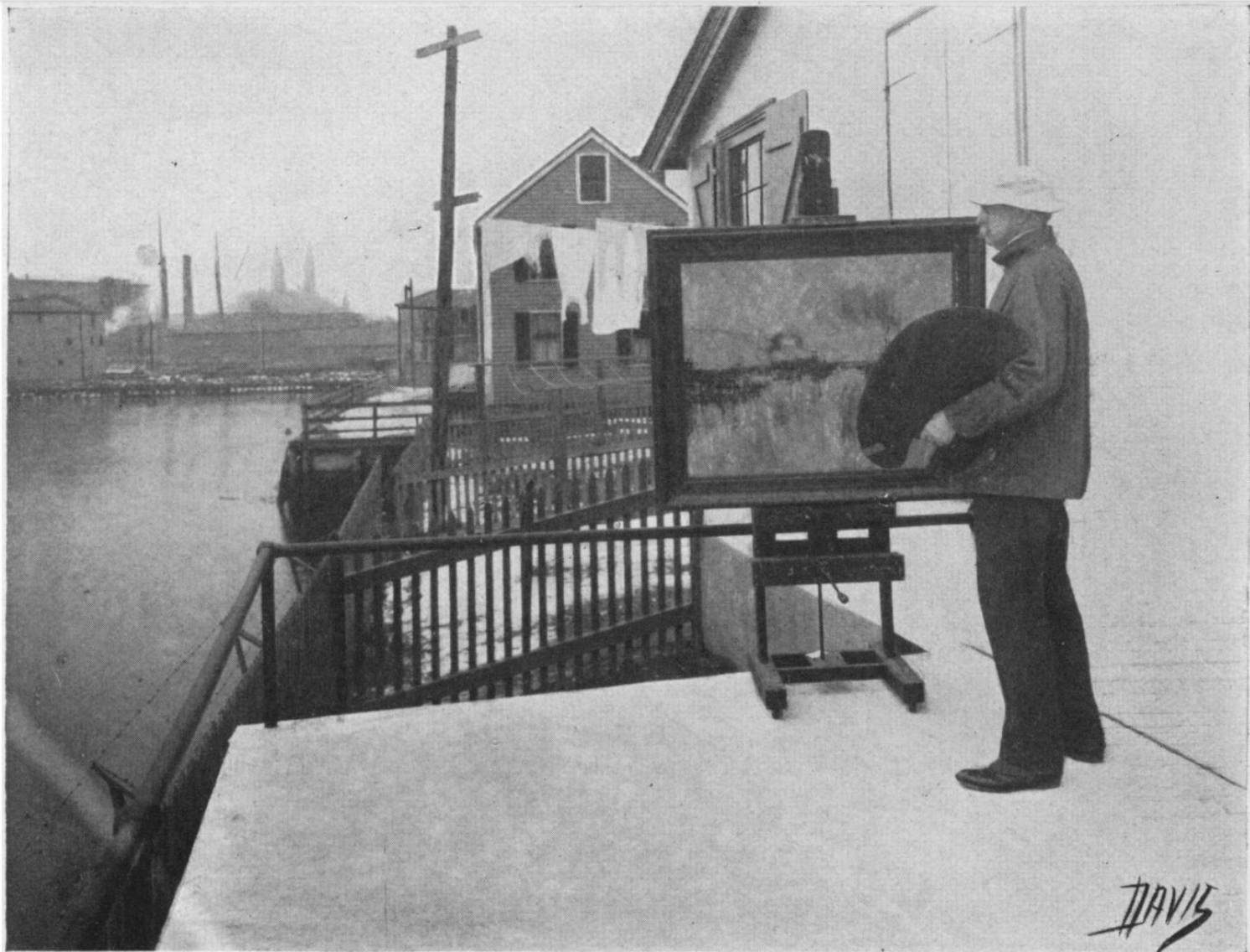

He was constantly fascinated by the coastal and maritime scenes of his beloved Massachusetts and so he set up his studio on a harbor in Salem where he could stand on his deck and paint the activity of the harbor – watching the way the light danced and moved throughout the day.

His style changed over the years but at the time he painted this work, Little had begun using impasto heavily. It adds a sculptural quality to the work – the texture catching highlights and casting shadows on itself – changing and interacting with its environment. The colors, from afar, visually blend creating what seems to be solid colors, when, if viewed up close, are actually a multitude of strokes of individual colors.

The Beauty of Art

This work can be seen as an epitome of the impressionist goal of portraying the interplay of light and color, not just in the colors the artist chose but through this use of impasto – the piece continually changing and interacting with its current light and surroundings.

The beauty of art, to me, is embodied in this work – that art is not just one thing, it’s many. It can have different meanings and different impressions on everyone. It is an experience that is not strictly black and white – it is all of the shades of gray in between. This work in and of itself is simultaneously many different paintings – it changes depending on the angle, the distance from which it is viewed, the brightness and hue of the light under which it is seen. It is both literal and indiscernible, muted but vibrant, still but vibrating with the radiant energy of changing light.

And I think the amazing thing about that is that viewing art doesn’t have to be about “right” or “wrong”. It’s simply about how truth and reality are multifaceted. It is so empowering to know that we don’t have to fear “getting it right”, and if we take the time to see things from a different perspective, we might be able to experience it in a whole new, wonderful way.

Be sure to watch the full episode here and stay tuned for new episodes the first Friday of each month!