I grew up near a small airport and loved watching the Cessnas and blimps fly low overhead and then land there. In college, I wrote my thesis about the history of that airport and fell in love with the history of flight. After I married, life took me in other directions, and I also fell in love with maritime history. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across a globe in the Collection at The Mariners’ Museum and Park, signed by Roscoe Turner, an aviator. My two historical loves combined!

The Mariners’ mission is pretty broad: through the waters – through our shared maritime heritage – we are connected to one another. The Collection has a little bit of everything, making this a unique and amazing place. Of course, I’m totally biased, but our Collection is one of the best in the world!

I often find unexpected objects in the Collection, but a globe signed by a barnstorming aviator? What in the world kind of connection does that have? Dig a little deeper and the story is there!

First, we must go back and learn more about who Roscoe Turner was and what’s on this globe.

BARNSTORMERS COMING THROUGH!

Turner was a pilot, but not just someone who flew from point A to point B. He was a barnstormer and air racer who wore a flashy blue uniform in the 1920s and 1930s, wowing audiences with crazy aerial antics. He even had a pet lion named Gilmore, who often flew the skies with him. That is until the cub grew too large for the cockpits and had to stay on the ground. Can you imagine the excitement Turner must have generated at each stop?

For an image of Gilmore and to learn more, check out this website!

Turner was a racer who won numerous awards. One particular race was the MacRobertson International Air Race in 1934, which had planes flying from London, England, to Melbourne, Australia. There were five required stops along the way, but otherwise, the pilots could choose their routes.

Our globe is super cool because Turner marked all the places he stopped during that race!

Sixty teams entered the race, but when it began, there were 20 planes in two divisions: speed and handicap. Roscoe Turner and his co-pilots, Clyde E. “Upside Down” Pangborn and Reeder Nichols, flew in a Boeing 247D. Nichols was the navigator, so the lack of a cool nickname in no way meant he didn’t have a super important job! The Americans finished in third place behind a British team and a Dutch team.

If you are super excited about this, like I am, then you will want to know that the airplane they flew still exists! It’s at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, which reopened to the public on October 14, 2022, after an extensive renovation. For an image of the plane, visit this website!

For contemporary video footage, check out the race updates below. Turner and his team are visible at 7:56 and 8:59 marks.

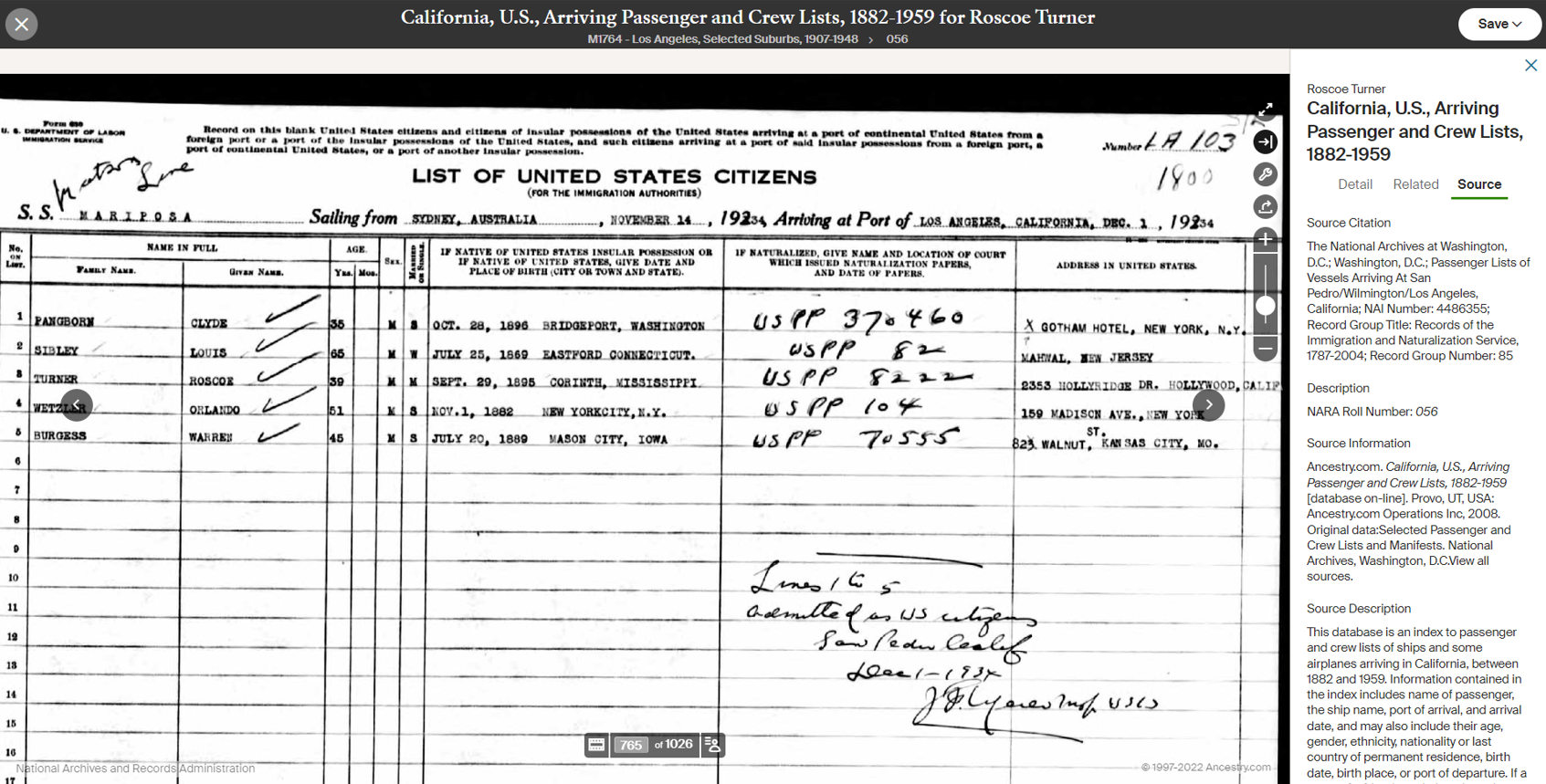

After the race, Turner and Pangborn returned to the United States aboard SS Mariposa, a Matson Line ship. It departed Sydney, Australia, on November 14, 1934, just a few weeks after the race ended, and arrived in Los Angeles on December 1.

MAKING CONNECTIONS

What’s so fascinating about the globe and the race is that they represent the changing nature of transportation in the early 20th century. A critical factor in the MacRobertson race was to prove that long-distance air travel was possible and could be accomplished in shorter times. The organizers also wanted to prove that passengers could be just as comfortable as other forms of transportation, like those sleek and elegant steamships.

One of the racing air teams even carried three passengers along with them! This almost ended tragically when the plane was lost in a storm over Albury, New South Wales, Australia. A radio announcer alerted the local people, who lined their cars along the runway so the headlights could guide the plane to a safe landing. Thankfully, the team landed safely and could continue the next day.

Of course, it wasn’t until after the technological innovations of World War II that the airlines could really take off (unintentional pun!), and the era of the regal passenger ship began to wane. Despite strong efforts to create that change, it took a while for air travel to gather the trust of the public and the financial stability to move forward.

A DIFFERENT KIND OF AIR TRAVEL

Airplanes weren’t the only vehicle in the skies in the early 20th century, and this globe isn’t the only air travel-related object in our Collection. Zeppelins were also a fascinating mode of transportation; the most well-known was the Hindenburg, which tragically caught fire in 1937. For additional details about that, visit our database here, and I’ll add this to my list of future blog posts.

AND ONE LAST CONNECTION…

The many objects in our Collection come to us in many different ways, each unique to the donor and the object. In this case, the globe was a bequest from Robert L. Hague, the vice president of the Maritime Division of Standard Oil. Here’s another great maritime connection: Hague was born in Rhode Island, where he left school early to join a fishing fleet. He sailed around the Caribbean for a while before jumping ship to learn a few land-based trades, then joined a different crew that sailed across the Pacific Ocean. Eventually, Hague started working as the superintending engineer for Standard Oil in California.

Before World War I, Hague’s draft registration card states that he was the assistant in charge of steel construction for the US Shipping Board. In this position, he helped overhaul ships to become military vessels during the war. With the experience he gained, he left the US Shipping Board in 1920 to work again for Standard Oil, this time on the east coast. Here, he eventually became the vice president of the Maritime Division, controlling the entire Standard Oil fleet as it moved around the world.

Hague died in 1939, and his obituary in the Chattanooga Daily Times described him as “‘the stage-struck sailor’ who headed the world’s largest privately owned merchant marine…” who left behind “a multifarious career that lifted him from the lowly hut of a fisherman.”

From newspaper accounts, Hague was a wealthy man who supported Broadway plays and the actors and actresses involved. He enjoyed the company of many famous people, so it’s possible he may have known Roscoe Turner. I wish I knew!

I’m not sure how Hague came to own the globe, but I can say for sure that the history it can tell is super fun. It involves the story of an air race and the larger story of the innovations that pushed along the transition of how people and goods move around the world. The changes came like dominoes, and today both ships and planes are essential to our world economy. Oh, what one globe can tell!

Sources

- American Shipping, Volume 11. United States, Shipping Publishing Company, Inc., New York, 1920, Pg. 38. https://www.google.com/books/edition/American_Shipping/sh3mAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=standard+oil+robert+hague&pg=RA7-PA38&printsec=frontcover

- “‘Bob’ Hague, Head of Oil Fleet, Dies.” The Chattanooga Times (Chattanooga, TN). March 9, 1939. https://www.newspapers.com/image/604463157/?article=6bc3324a-0754-4ce9-b864-7b45cae365b0&focus=0.017239705,0.041539807,0.13995896,0.44651476&xid=3355&_gl=1*xhm7w9*_ga*MjcyNjYyMDczLjE2NTQ2MjUyMjY.*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*MTY1OTM3MzQzMS4yNC4xLjE2NTkzNzQyNTAuMA..&_ga=2.111810500.1719395991.1659353866-272662073.1654625226

- World War I Draft Registration Card for Robert L. Hague, Ancestry.com. U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. Original data:United States, Selective Service System. World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. M1509, 4,582 rolls. Imaged from Family History Library microfilm. Accessed 18 October 2022. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/29661534:6482

- New South Wales State Library. “Aviation in Australia: MacRobertson Centenary Air Race.” Accessed 18 October 2022. https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/aviation-australia/macrobertson-centenary-air-race

- Ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.Original data: US City Directories Database, 1822-1995. San Francisco, California, 1915, page 852. Accessed 18 October 2022. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/230871731:2469

- Smithsonian Institute. “Early Commercial Aviation, 1914-1941.” Accessed 18 October 2022. https://airandspace.si.edu/explore/stories/early-commercial-aviation

- Gert Jan Mentink, “The Great Air Race to Melbourne: The 1934 MacRobertson Trophy.” AirHistory.net. Accessed 18 October 2022. https://www.airhistory.net/text/events/macrobertson-melbourne-air-race-1934.php

- Jack Patterson. “Turner: Showman of the Air.” The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, OH). June 26, 1970. https://www.newspapers.com/image/legacy/145421671/?terms=roscoe%20turner&match=1