The Manifest Destiny concepts of western expansion began to move the United States closer and closer to war with Mexico. The annexation of Texas did not resolve the issue of a disputed border between Texas and Mexico. Mexicans claimed the border was along the Nueces River, whereas Texans believed that the border should be the Rio Grande. This circumstance prompted President James K. Polk to send an Army of Occupation, commanded by Brigadier General Zachery Taylor, to the Rio Grande. There, Taylor established a star defensive work known as Fort Texas, overlooking the river. Mexicans viewed this as a violation and threat to their sovereignty.

They responded accordingly. On April 25, 1846, units of the Mexican army, commanded by General Marino Arista, attacked and captured a small US scouting party. Arista then besieged the American fort. Taylor then brought his 3,400-man army to the Rio Grande and defeated Arista’s army on May 4, 1846, during the Battle of Palo Alto and again on May 9, 1846 at Resca de la Palma. The Mexican army retreated. Upon hearing news of Taylor’s victories, Polk sent a message to Congress claiming Mexico had invaded US territory. A Declaration of War then followed. Taylor’s victories created a “war fever”’” throughout the nation, and many men volunteered to fight to expand the nation’s “rightful” boundaries to the Pacific Ocean.

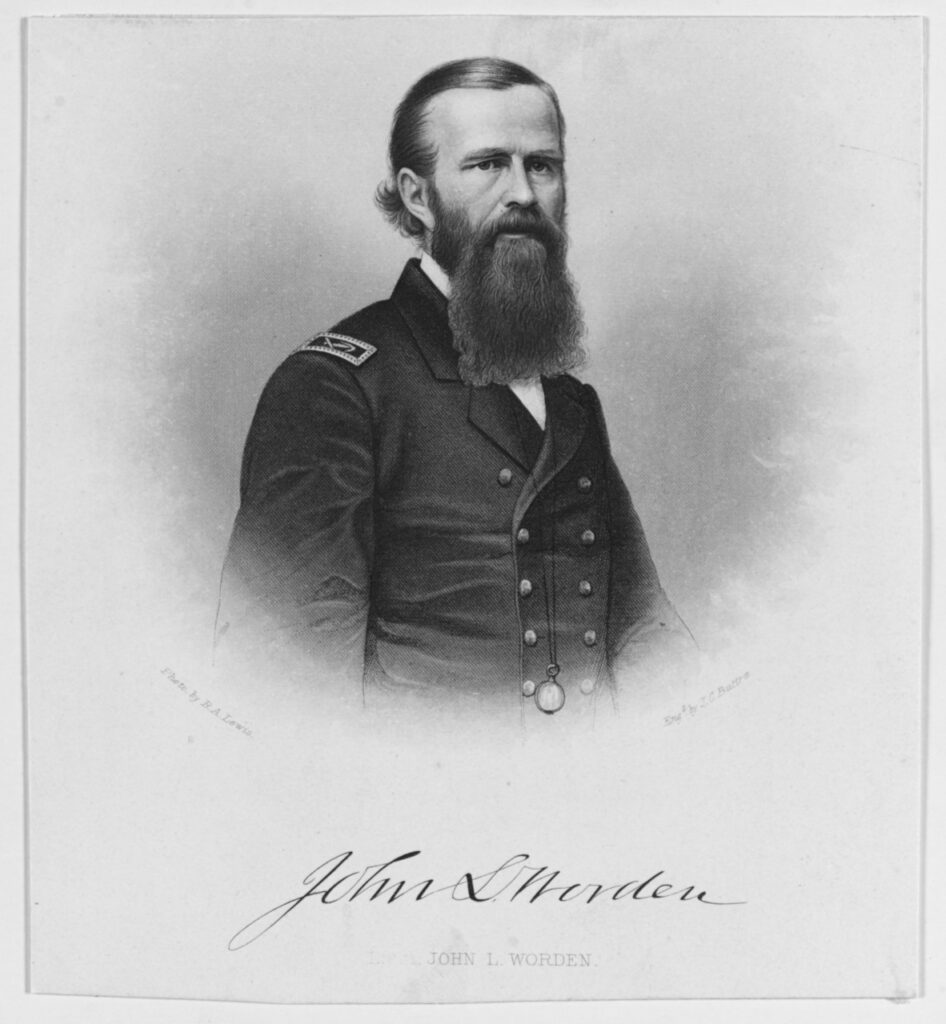

These actions must have motivated John Worden to request to be detached from the USNO on May 26, 1846. Most young officers sought active service. With the war being fought along the Gulf and Pacific coasts, it appeared to be a grand opportunity for a naval officer to attain laurels which could surely advance their career. Worden requested leave until he was called for sea duty. His request was granted, and he moved his family to Quaker Hill, Dutchess County, New York. This leave allowed the Worden family to share quality time together. On October 10, 1846, Worden moved to New York City. Sadly, Worden’s grandmother, Lucretia Garrison Worden, died on November 15. (1)

While on leave, Worden was warranted a master, in line for promotion, on August 15. Worden had already been nominated to be promoted, on August 4, by President Polk, to be named a lieutenant along with Napoleon Collins and DeLancey Izard to fill the vacancies occasioned by the promotions of Henry Pinkney, William Glendy, and George Upshur. The Navy needed more officers to staff all the ships and crews necessary to blockade the Mexican coastline. Worden’s promotion was approved by the US Senate Committee on Naval Affairs on January 11, 1847, along with several other officers such as Henry P. Robertson, Randolph F. Mason, Issac N. Brown, and Joshua Huntington.

Accordingly, Worden was promoted to lieutenant, to date from November 30, 1846, on January 18, 1847. He filled the slot vacated by the death of Lieutenant Charles Morris. Morris, who had been assigned to USS Cumberland, died due to wounds he received during the abortive attack on Tabasco, Mexico, on October 26, 1846. Morris was part of a 253-man landing force led by Cumberland’s commander, Captain French Forrest. The Navy’s ability to quickly move up and down the Mexican coast with no opposition gave the Americans a distinct advantage. Ships, whether steamers or sail-powered, could position bluejackets, Marines, and artillery anywhere, which enabled the blockade to be maintained and Mexican port cities captured. (2)

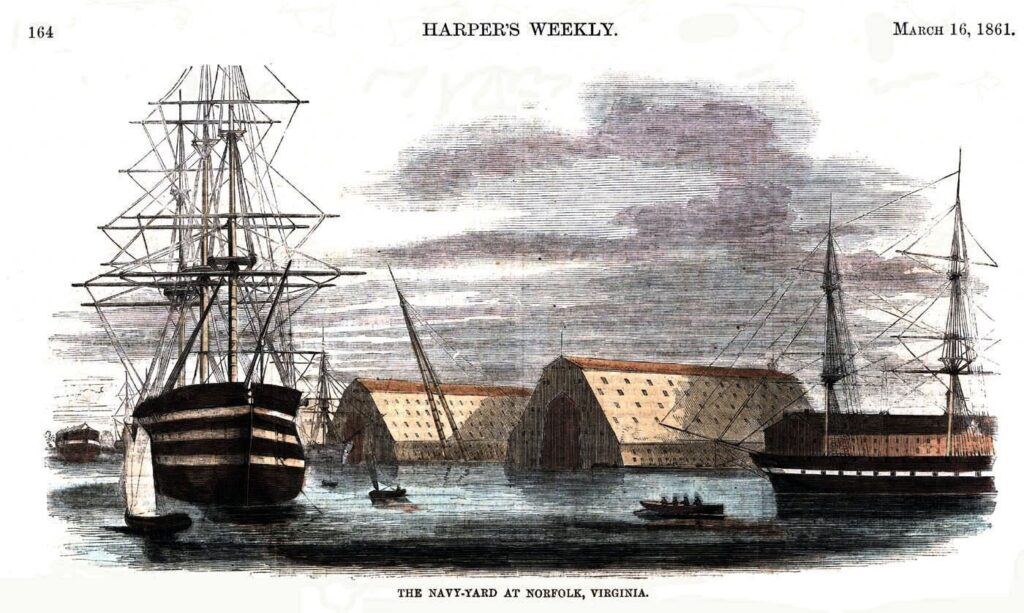

The newly minted lieutenant was detailed to the store ship USS Southampton, berthed at Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth across the Elizabeth River from Norfolk, on January 29, 1847. Worden traveled from New York City to Norfolk and reported to Gosport Navy commandant Commodore Charles W. Skinner on February 3. He assumed his position as executive officer of Southampton on February 5. The vessel was commanded by Lieutenant Robert D. Thornton. The ship remained at Gosport Navy Yard until Southampton stood out to sea on February 17, 1847. Contrary winds delayed the warship from clearing the Chesapeake capes until February 23. (3)

It was an uneventful cruise until the ship reached Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on April 12, 1847. There they met the 50-gun frigate USS Columbia which was the flagship of Commodore George Washington Storer, commander of the Brazil Squadron. A 13-gun salute was given in honor of the commodore. Then Southampton hoisted the Brazilian flag at her foremast, which called for a 21-gun salute from the American warships. In return, the city fired a 21-gun salute. When the smoke cleared, the American minister to Brazil, Henry Alexander Wise of Virginia, toured Southampton without any fanfare. Worden coordinated the reconstruction of staterooms, which were in a “very leaky condition.” He also organized the receipt of fresh provisions and three cases of wine to be delivered to Valparaiso. While in port, several men deserted; nevertheless, Worden was able to recruit replacements. (4)

While Southampton was en route to Rio de Janeiro, much had occurred back in the United States relating to Worden’s personal life. The memorial that had been submitted to by Worden to secure back pay for his service as acting master of USS Relief, even though he was just a passed midshipman. On March 3, 1847, the Committee of Naval Affairs discharged this memorial from further consideration. Nevertheless, Worden would eventually receive excellent news that his second son, Daniel Toffey Worden, was born on April 27, in New York City. (5)

Southampton left Rio de Janeiro on April 21, 1847, for Valparaiso, Chile. This Chilean port city was a common port of call for US naval vessels to resupply after or before rounding the Horn. Generally, rounding Cape Horn was often an extremely rough and dangerous voyage. Often, old sailors would say that they were crossing near the end of the earth. Fortunately for the storeship, as the vessel approached the cape on May 14, the weather was described as being “moderate breezes and cloudy with snow and rain.” When the store ship reached the Pacific Ocean on May 20, the conditions were described as being “light variable breezes and foggy damp weather.”

These six days of Southampton’s voyage were achieved quickly and without incident. Lieutenant Worden was standing watch as the warship stood in for the harbor of Valparaiso on June 17, 1847. The voyage had already taken four months, which is indicative of the communications problems associated with the operation of the Pacific Squadron. (6)

While in Valparaiso the port, Worden resupplied Southampton after the vessel’s long voyage from Brazil. From June 17 to 22, 1847, the store ship received fresh beef and vegetables as well as 4,000 gallons of water and 8,050 sticks of firewood. These goods were to supply the ship for the final leg of its journey. Crew members were permitted to go on liberty, which Worden oversaw, as Valparaiso was the last solid ground they could walk on for another two months. The storeship stood out from the Chilean port, with Worden serving watch, on June 24 en route to California.

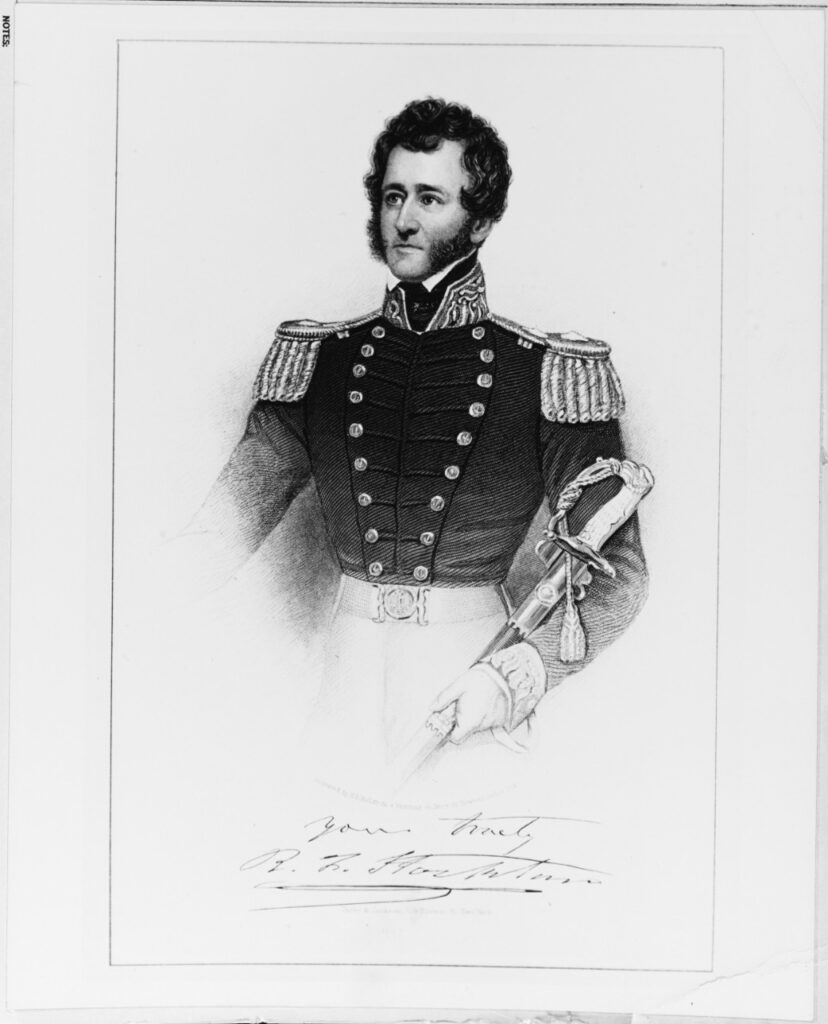

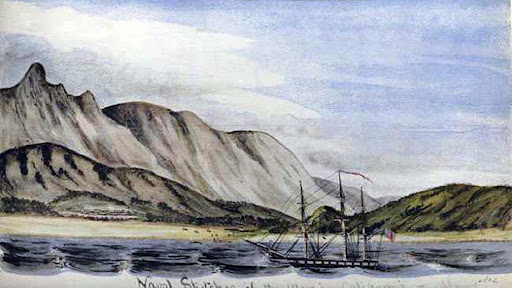

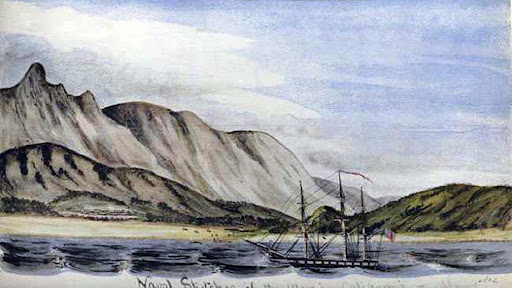

When Worden’s ship arrived in Monterey, California, on August 17, 1847, much had occurred in Alta and Baja California. Commodore John Drake Sloat was the Pacific Squadron commander when the war erupted. Sloat did not learn about the war until July 7, 1846, and immediately captured Monterey. The same day, the sloop of war Portsmouth occupied Yerba Buena (today’s San Francisco). Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft dispatched Robert Field Stockton to command the Pacific Squadron. Bancroft wanted Stockton to act more aggressively and in conjunction with the explorer Captain John C. Fremont’s California Battalion.

Fremont had over 300 men. Fremont’s command, supported by Stockton’s ships and personnel, conquered all of Northern California. The Americans then focused on Southern California. While Los Angeles was initially abandoned by the Californios, they reorganized and forced Stockton’s forces back to their ships. Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny, USA, arrived on the scene after a hard march from Santa Fe, New Mexico, and joined forces with Stockton’s naval forces to defeat the Californios during the battle of Rio San Gabriel, January 8, 1847. The next day, all Californio resistance was crushed at La Mesa. These engagements ended the military conflict in Alta California, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13, 1847. (7)

A new conflict arose between Commodore Stockton and Brigadier General Kearny. Even though Kearny’s orders entailed that he should assume the position of military governor of Alta California, the commodore disagreed. Stockton ignored Kearny and formed a government with John C. Fremont as military governor on January 16, 1847. The very next day, Fremont advised Kearny that he would only take orders issued by Commodore Stockton.

Kearny did not reply and awaited reinforcements. (8) Commodore William Branford arrived and replaced Stockton as commander of the Pacific Squadron. Kearny hastened to Monterey to meet Shubrick, and they agreed to work together. On March 1, Kearny and Shubrick issued a joint proclamation detailing that the Navy would be responsible for customs and port duties, leaving the Army in charge of the civil governance. Earny replaced Fremont as governor and placed him under arrest for insubordination. They returned east together for the trial. (9)

The Pacific Squadron was now on the move, and USS Southampton would soon play a very active role in Baja California. Meanwhile, the store ship had to perform its purpose. John Worden, as the storeship’s executive officer, did not have to stand watch often because he was responsible for the organization and management of the ship’s operation as well as the acquisition of supplies to the various ships of the Pacific Squadron. The storeship’s primary purpose was to supply the squadron’s warships as they worked away from a friendly port.

As soon as Southampton arrived in Monterey, Worden organized the receipt of fresh beef and vegetables for the store ship’s crew as well as other supplies for distribution. The ship’s first receiver of supplies was the US frigate Independence. One barrel of butter was transferred to the frigate on August 19. On the same day, the executive officer ordered Carpenter’s Mate Anthony Woodhouse to boil linseed oil on the beach. Monterey, which was then California’s capital, had a large naval storehouse from whence Worden could re-supply his ship, enabling Southampton to provide provisions and other goods for the squadron warships.

At the end of August 1847, Worden was extremely busy with this duty. On the 28th, Southampton supplied USS Portsmouth with 12 barrels containing 431 gallons of whiskey and 933 pounds of rice, as well as providing Congress with two barrels containing 2,992 pounds of bread. The next day, Worden orchestrated the delivery of 11 barrels of rice and 27 barrels filled with 955 gallons of whiskey to the frigate. The following day, Southampton was sent 12 bags, “said to contain 1040 pounds of sugar,” as well as almost 600 gallons of water. (10)

In addition to his work providing goods to the Pacific Squadron and the Monterey storehouse, the executive officer had to ensure that the vessel completed essential maintenance. He secured the services of USS Warren’s sailmaker on August 25 and 31 to mend Southampton’s foresail. On September 7, Worden put the crew to work painting yards and mast heads. Later in September, he had the crew get-up a new main trysail gaff. Before sailing to its next destination, he obtained from the storehouse “25 lbs 4 & 5 nails and fifty gallons white paint” for future ship repairs. (11)

While a store ship, Southampton was also an active warship serving in hostile territory. Even though the vessel was armed with just two 42-pounder carronades, Worden mustered the crew at quarters to practice working the guns. After significant training operating these heavy, short-barreled guns, Worden had the guns secured. During the time spent in Monterey, he also trained certain crew members with small arms. Not only would this skill be rather useful in defending the ship, but also when crew members were assigned to shore excursions. (12)

Although many expected Southampton to soon head south, the loaded storeship instead set sail north to San Francisco on October 12, 1847. En route, the storeship encountered an unknown schooner on October 14. Worden had the ship’s colors raised and then fired a shot across the bow of the mystery ship. The schooner quickly displayed the French tricolor. The next day, Southampton arrived at San Francisco and anchored in Yerba Buena Cove. Worden immediately put the crew to work securing ordnance supplies for use in Baja California.

The executive officer assigned enlisted men to rig sheers (block and tackle) to haul artillery onto his ship. Commodore Shubrick, then with elements of the Pacific Squadron in the Gulf of California, had requested that Col. Richard Mason provide seacoast mortars to support the commodore’s operations. Two 10-inch mortars were loaded into the Southampton. It was extremely difficult work as each mortar weighed 5,775 pounds.

In addition to these huge guns, Worden guided the men loading other ordnance material on October 16, such as eight hand spikes, four wheel barrows, two water buckets, three boxes containing 72 spades, three boxes with pickaxes & handles, two boxes with 20 crowbars, two piercing wires, two gunners gimblets, two fuse saws, two fuse setters (wood), two fuse extractors, two fuse mallets, two sets of powder measurers, and two gunners quadrants. More gunnery supplies were loaded on the next day, including one box containing 200 mortar cartridges, 200 10-inch shells, and one box marked to contain 200 10-inch fuses. (13) Then Southampton stood out from San Francisco on October 19 and reached San Diego on November 5. The next stop would be the Gulf of California combat zone.

Once Alta California was completely controlled by US forces, Secretary of the Navy John Y. Mason had ordered Commodore Stockton, before his replacement with Shubrick, to occupy Baja California and blockade Mexican Pacific coast ports. One of Polk’s administration’s war aims was to annex Baja California and the Mexican state of Sonora. Stockton intended to ensure that these expansionists’ dreams were fulfilled. The commodore, believing that all of Alta California was completely under US control, proclaimed that “having by right of conquest taken possession of that territory by the name of Upper and Lower California do now declare it to be a territory of the United States under the name of the territory of California.” (14)

As Commander John B. Montgomery’s orders were to show an American presence also at San Jose del Cabo, La Paz, and Loreto, the sloop soon left Mazatlan. Portsmouth then sailed to San Jose del Cabo which was a small farming and fishing village located at the very tip of the Baja Peninsula. The town was captured on March 30, 1847. The sloop then moved up the coast and forced San Luca to surrender. Because he lacked sufficient manpower, Montgomery could not leave a garrison at any of these coastal Baja towns. Portsmouth reached La Paz on April 13.

The next day, Colonel Miranda surrendered La Paz. The local citizenry signed the articles of capitulation. This document had rather unusual provisions which granted them United States citizenship rights; yet, they were allowed to retain their own officials and laws. Not all Baja Californios accepted this collaboration. Loyalists gathered about 20 miles north of San Jose at Santa Anita. They declared that Miranda was a traitor and proclaimed Mauricio Castro as the new governor, with the volunteers placed under the command of Captain Manuel Pineda. (15)

Meanwhile, General Kearny had been preoccupied with securing the safety of the American positions in Alta California. On April 23, Kearny received orders to send troops to occupy a portion of Baja California. He delayed this action because he had insufficient soldiers, and he wanted to confirm the political discord in Mexico. Just before Kearny headed east, the 1st Regiment of New York Volunteers arrived. This unit, also referred to as the New York Legion or the California Guard, had traveled from New York City around Cape Horn to Monterey in four vessels.

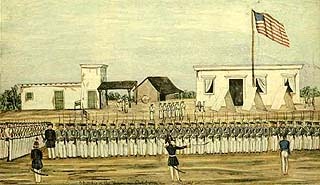

The unit had been recruited by New York state legislator Jonathan D. Stevenson. Stevenson had advised all of the volunteers that they would be mustered out of service, once their duty had been performed, in California. Stevenson was named colonel of the regiment, and his executive officer was Lieutenant Colonel Henry Stanton Burton. Burton graduated from West Point in 1839 and had previously served as 1st lieutenant, 3rd US Artillery Regiment. On April 30, 1847, Kearny ordered Col. Burton and Companies A and B of the First Regiment of New York Volunteers to embark on the store ship USS Lexington, commanded by Lieutenant Theodorous Bailey. The ship left Alta California on July 4, 1847. Lexington arrived at La Paz 17 days later. Burton’s men waded ashore and quickly established an outpost on a rise outlooking the town and harbor. (16)

Col. Burton reinstated civil government. His men certainly enjoyed their station at La Paz. Lt. E. Gould Buffom thought the village was the prettiest he had ever seen in California, noting that the “houses were all adobe, plastered white, and thatched with the leaves of the palm tree, and were delightfully cool. The whole beach was lined with palms, dates, fig, tamarind and coconut trees, their delicious fruit hanging down on them in clusters.” (17) While the occupation of La Paz seemed almost idyllic, there was serious trouble brewing to the north.

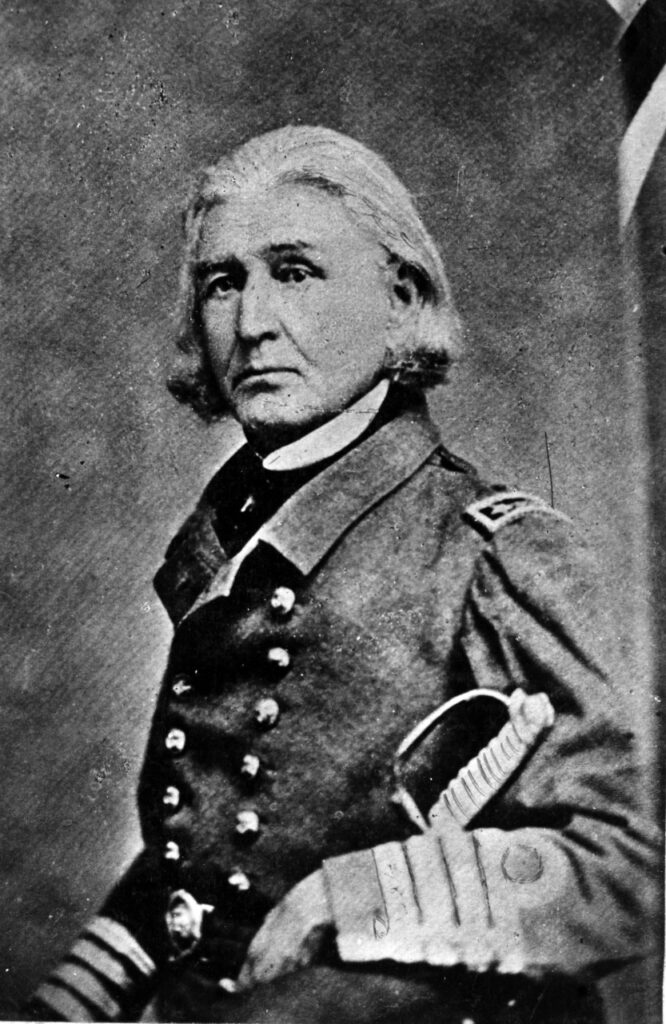

In the meantime, Commodore William Branford Shubrick sortied from Monterey with Independence, followed by Cyane. On October 29, These ships joined with Congress, and anchored off San Jose del Cabo. Shubrick wished to enforce American control over the peninsula. The commodore proclaimed on November 4 that the purpose of his campaign was to permanently conquer Baja California. Much of the local population was overjoyed by this announcement and actively supported the American occupation. A small garrison of Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Heywood, was left in San Jose del Cabo to enforce US control. Heyward established his force in an old, run-down mission building and house overlooking the village. (18)

The commodore then moved his main force, Independence, Congress, and Cyane, to Mazatlan and demanded the surrender of the town on November 11. Lieutenant Colonel Telles commanded a defensive force of about 560 soldiers; however, he had not made any effort to build fortifications to protect the town from the Americans. Accordingly, he withdrew from the town when the American warships appeared to set up camp at Palos Prietos. Telles also refused Shubrick’s demand that his force surrender. On November 11, Captain LaVallette of Congress took a 730-man landing party ashore and quickly occupied Mazatlan. The American flag was raised, and LaVallette issued military regulations, including the collection of custom duties. He did not otherwise disturb the citizenry. Lieutenant Henry W. Halleck, an 1831 graduate of West Point, went ashore with the landing force and laid out fortifications. Four hundred sailors and Marines were left to garrison the town. (19)

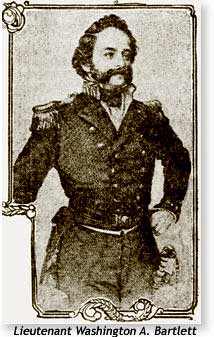

Meanwhile, Southampton neared the Gulf of California on November 11, 1847. While at sea, Lt. Worden had drilled the crew in small arms techniques in preparation for duty in a war zone. Worden noted in the ship’s log on November 11, that the ship passed an American whaler and, while he was still on watch, met Lieutenant Allen Barlett of the brig Caroline. Barlett had been the first American alcalde (mayor) of Yerba Buena and had renamed the town San Francisco in January 1847. (20)

Southampton reached San Jose del Cabo on November 14. The store ship anchored in the harbor. Lt. Worden took the No. 2 cutter to the shore in order to communicate with Lt. Heywood’s garrison. Worden knew Heywood from his prior cruise aboard Cyane. Seeing that all seemed well, the storeship then upped anchor and stood out for Mazatlan on November 16. (21).When the storeship arrived in the port’s large anchorage, Worden immediately noticed the American flag flying over the Quartelle (barracks). All of Shubrick’s squadron was at Mazatlan, including Independence, Congress, Portsmouth, and Cyane. The commodore sent signals to Southampton, which Worden deciphered. He noted that the squadron had added several vessels, such as the brig steamer Scorpion (No. 90) and several bomb gun (mortar) vessels, such as the Vesuvius (No. 92) and Hecta (No. 93), as well as some smaller support vessels. (22)

Worden then organized the resupply of the squadron for the next 10 days. On November 17, Cyane received three boxes of 399 lbs of tobacco and three barrels of whiskey. Southampton delivered to the Congress over the next several days 10 barrels of bread totaling 998 lbs., two barrels of flour, 34 half-barrels and 34 full barrels of beef, 18 barrels of pork, 14 boxes containing 372 pounds of tea, 25 barrels of 7,047 lbs.

Of sugar, three barrels of flour, 713 pounds of butter, and 1144 lbs. of rice. These supplies were delivered separately to the frigate’s personnel serving in defensive positions: 431 gallons of whiskey, 25 barrels of beef, and another 25 barrels of pork. The frigate was given even more supplies on November 21, including 632 lbs. of butter, 1785 lbs. of rice, 352 gallons of vinegar, eight barrels of molasses, 16 barrels of pork, and four half barrels of beef. (23)

By November 23, Commodore Shubrick had learned about the uprisings on the lower Baja peninsula. Intelligence informed him that loyalist Californios had attacked Lt. Heywood’s position in San Jose del Cabo, The commodore detailed Southampton to return to that port to support American control. Worden noted that as the storeship was being hauled out of Mazatlan’s harbor, it received eight Marines (one sergeant and seven privates) from Portsmouth as supernumeraries. The flagship, according to Worden, then supplied Southampton with a quantity of grape and canister shot, musket cartridges, and other ammunition to resupply the fort at San Jose del Cabo. As Southampton sailed south from November 25, 1847, to November 27, 1847, Worden exercised the crew with small arms on a few occasions. He also supervised the repair of the ship’s small arms. Worden knew that his ship was headed toward a possibly dangerous situation and wanted to have the crew ready for any circumstance that might occur. (24)

Southampton’s arrival off San Jose del Cabo on November 28, 1847, was a welcome sight by Lt. Charles Heywood. His fortified position within an old mission and house (referred to as Mr. Mott’s house) had been under great stress by the Loyalist Californios. The structure was on high ground overlooking the town. Heywood had one 9-pounder gun to enhance his defenses and a four-week supply of provisions. The garrison consisted of 28 Marines, four passed midshipmen, and 20 pro-American Californios volunteers.

Loyalist Captain Pineda decided to strike against the Americans at both San Jose del Cabo and La Paz. Pineda sent a force of 150 irregulars, under the command of Lieutenant Vicenta Mejia against the American position. On November 19, Mejia demanded that Heywood surrender, which he refused to do. The Mexicans attacked later that day and were forced to retreat. The next night Lt. Mejia led an assault to capture the 9-pounder gun position.

The assault failed, and Meija was killed. Mejia’s force had three more killed, and three American personnel were wounded. Pineda then decided to besiege the American position; however, two American whalers, Magnolia and Edward, appeared in the harbor. Pineda took these vessels as American warships. Since he knew that the heavy guns of the US warships made it impossible for Pineda’s command to capture American outposts. Consequently, the Mexican commander combined these troops with his effort to capture La Paz. (25)

Southampton had been sent to San Jose del Cabo to reinforce and resupply Heywood’s garrison. Immediately upon the storeship’s arrival in the harbor, Worden, with a pilot and eight men, took a cutter ashore to contact Lt. Heywood. The executive officer brought with him the ship’s surgeon, Dr. James McClellan. The doctor attended to the garrison’s sick and wounded as Worden assessed the situation. He then organized an effort to support Heywood’s defenses.

He immediately sent 10 Marines to reinforce the American position. Worden then began the process of transferring to the mission a 12-pounder carriage gun, 29 12-pounder cartridges, 10 round shot, 10 stands of grape shot, five canister shot, rammers, spongers, powder horn, and priming wires. The lieutenant detailed Carpenter’s Mate Anthony Woodhouse ashore to properly mount the gun atop the Mott house and made other improvements to the American defenses. To further reinforce Heywood, Worden sent Passed Midshipman Henry K. Stevens with 60 bluejackets to add to the American on-shore force. The executive officer also provided food, candles, and other necessities, including 343 gallons of whiskey for Heywood’s command. (26)

Once the San Jose del Cabo situation had been stabilized, Southampton was detailed to resupply Lieutenant Colonel Henry S. Burton and two companies, A and B, of the 1st Regiment of New York Volunteers at La Paz. Burton’s troops were the first to arrive in the Gulf of California combat zone, and Commodore Shubrick had quickly assigned them to the defense of La Paz. Pineda’s forces were now pressuring the American position.

Southampton was loaded with additional supplies such as Paixhans shells, food, water, and whiskey. The supply ship left San Jose on December 6, setting sail for Guaymas, arriving there on December 20. With assistance from USS Dale’s boats, Southampton was towed into the harbor. Due to the heavy weather encountered en route to Guaymas, the storeship required significant repairs to its sails. Southampton then began its resupply of Dale, beginning on December 21. Simultaneously with Dale receiving supplies, the sloop sent several shells striving to strike enemy troops in the town. (27)

Meanwhile, Worden organized the transfer of two 32-pounder shell guns with equipment from Dale to Southampton. They were mounted on the port side of the storeship. Simultaneously, Worden guided the hoisting of a 10-inch mortar out of Southampton and onto one of the sloop’s launches. The mortar was then transported to Little Almagre Island (Isle Almagre Chico) near the entrance to Guaymas Harbor. All the supplies, equipment, and ammunition needed to operate this large siege weapon were also offloaded. When the bluejackets hauled the gun into position, it was test-fired, and one of the trunnions broke off. The broken trunnion was sent back to Southampton, and the second 10-inch mortar was taken out of the storeship and sent to the island. Under Worden’s command, Gunner William Myers managed the replacement mortar. It sent three shells into Guaymas on December 24, and three more struck the town the next day. (28)

On January 7, 1848, under a flag of truce, Worden, Passed Midshipman Henry K. Stevens, and Gunner William Myers went to deliver a communication to ‘Grnl. Commanding Sonora. On January 20, Worden was placed in command of the prize schooner Fortuna. It was his first ship command, and he armed it with a medium 12-pounder. Worden’s command included Purser’s Clerk M.D. Winship, a pilot, and a crew of ten well-armed bluejackets. Fortuna got underway for a brief cruise along the coast, towing Southampton’s third cutter. Worden then secured 430 gallons of water from the schooner Libertad. One week later, Worden, his command, and armaments returned to the storeship as Fortuna was left in a secure anchorage. (29)

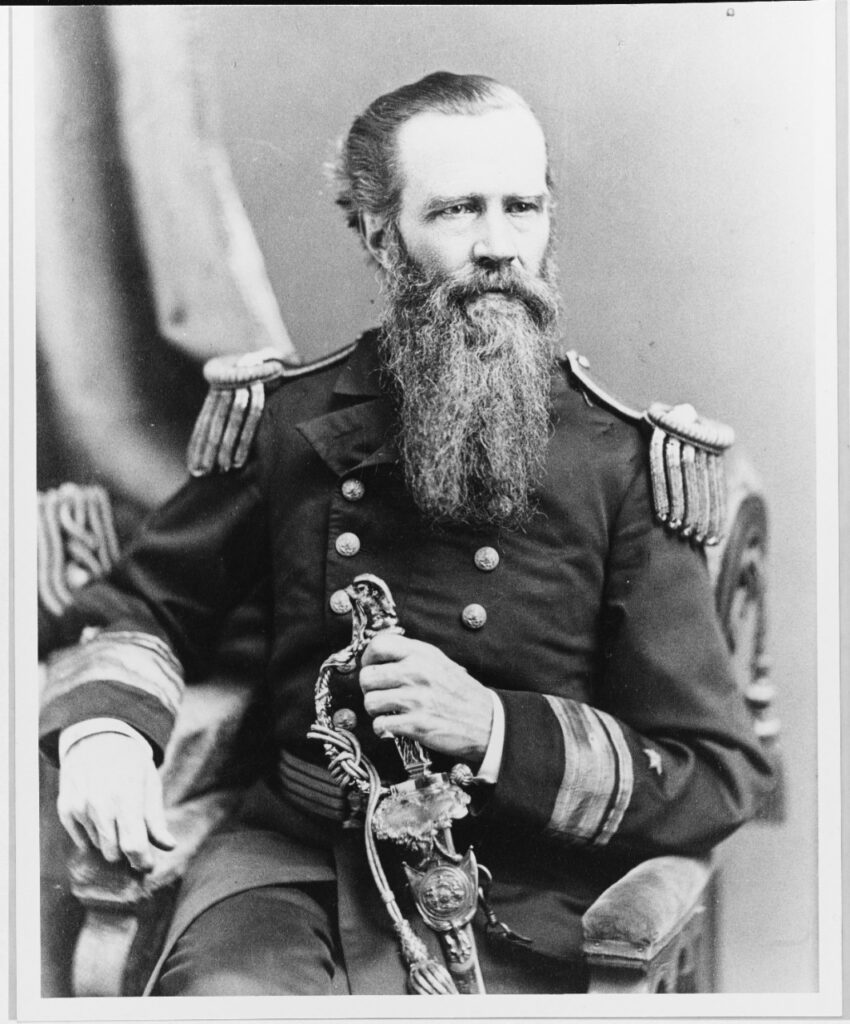

John Worden was placed in command of a launch on March 2, 1848. Lieutenant Henry W. Halleck was attached to his command along with an eight-man crew. Their duty was to harass Mexican shipping. Worden soon captured the schooner Rosita and returned it to La Paz on March 10. From April 1-6, Worden commanded several expeditions from Southampton to defend La Paz and the American supplies stored there. This would be his last duty during the Mexican War, as he was admitted to the infirmary for gastric derangement. Commodore Shubrick ordered the transfer of Lieutenant John L. Worden, “in consequence of ill health,” from the storeship Southampton to the ship of the line Independence. (30)

Sources:

1. HR Report 1776.3. “Record of Service of Rear Admiral John L. Worden,” John Lorimer Worden Papers, Lincoln Memorial Library and Museum; and Worden, Hydrographic Office, Washington, to Secretary of Navy George Bancroft, May 26, 1846. Officers Letters, Microfilm Publication, M148, Roll 174, NARA.

2. “The Naval Board Promotions,” ALEXANDRIA GAZETTE (VA), August 7, 1846; JOURNAL OF THE EXECUTIVE PROCEEDINGS OF THE SENATE, 1845-1846, p.160; and “Appointments by the President,” ALEXANDRIA GAZETTE (VA), JANUARY 18, 1847.

3. Worden, Quaker Hill, to Secretary of Navy John Y. Mason, February 3, 1847, Office Letters, Microfilm Publication M148, Roll 178.NARA; Storeship SOUTHAMPTON-Secretary of the Navy, Register of the CommissiC. Alexander, 1847,121); and USS SOUTHAMPTON-US Ship Logs, RG 24 E118, vol. 3, Feb.9, 1847-April 11, 1849.

4. USS Southampton Log

5. IBID.

6. IBID.

7. Cooke, Philip St. George, THE CONQUEST OF NEW MEXICO AND CALIFORNIA, AN HISTORICAL AND PERSONAL NARRATIVE, Albuquerque, New Mexico: Horn and Wallace, pp. 2648; CLark, KERANY, 249-53; Bauer, SURFBOATS AND HORSE MARINES, 196-9.

8. Kearny to Stockton, Jan 17, 1847, KLB, 90-1; Baynard, SKETCH OF STOCKTON, 147-8; Clark, KEARNY, 249-253.

9. Bauer, THE MEXICAN WAR, p.194-6.

10. USS Southampton Log

11. IBID

12. IBID

13. IBID.

14. Stockton Proclamation, Aug. 19, 1846, H.Ex Doc, 4, 2d Sess., 64701, Mason to CO Pacific, Dec. 14, 1846.

15. Richard W. Amero, “The Mexican War in Baja California,” SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY, Winter 1984, Volume 30, Number 1, https://sandiegohistoryorg/hournal/1984/january/war Retrieved 17 May 2020, and Peter Gerhard, “Baja California in the Mexican War, 18461847,” PHR, XIV (November 1945), 413.

22. DuPont to Stockton, Dec.1 1846, W.Radford et.al. to Hull, Sept. 11, 1846; Colton, THREE YEARS IN CALIFORNIA, 81-82; Sphia Radford de Meissner, OLD NAVAL DAYS, 138.

23. Bauer, 344.

16. Francis D. Clark, THE FIRST REGIMENT OF NEW YORK VOLUNTEERS(New York; 1882), p. 24; MEMORANDUM OF CAPTAIN H.W. HALLECK CONCERNING HIS EXPEDITION IN LOWER CALIFORNIA, 1846-1848, BLIC, 11.

17 Amero.

18. John Haskill Kemble, (ed.), “Amphibious Operations of a Cruise in Gulf of California,” THE AMERICAN NEPTUNE V (April 1945)pp.122-125;

Charles Belknap (ed.), “Notes from the Journal of Lieutenant T.A. M. Craven, USN, USS DALE, Pacific Squadron 1846-49,” USNIP, XIV (June 1888), 304-7; Bauer, SURF BOATS AND HORSE MARINES, 211-13.

28 Kemble, “Amphibious Operations in the Gulf of California,” 125; Belknap, “Notes from the Journal of Craven,316; Gerhard, Baja California in the War,” 420; Bauer, Surf Boats and Horse Marines, 218-219.

29 Shubrick to Mason, Nov.4,Nov.5, Dec. 7,1847, H. Ex. Doc. 1, 30th Congress, 2d Sess, 1058.

19. Halleck, MEMORANDUM, 14-15, 38-39.

20. USS Southampton Log

21.IBID.

22.IBID.

23 IBID.

24. IBID.

25. K. Jack Bauer, THE MEXICAN WAR, 1846-1848. P. 348.

26. USS Southampton Log

27. IBID.

28. IBID.

29 IBID.

30. “Record of Service of Rear Admiral John L. Worden.” p. 2, John Lorimer Worden Papers, A80-1364, University Archives and Special Collections, Lincoln Memorial University, Harrogate, TN.