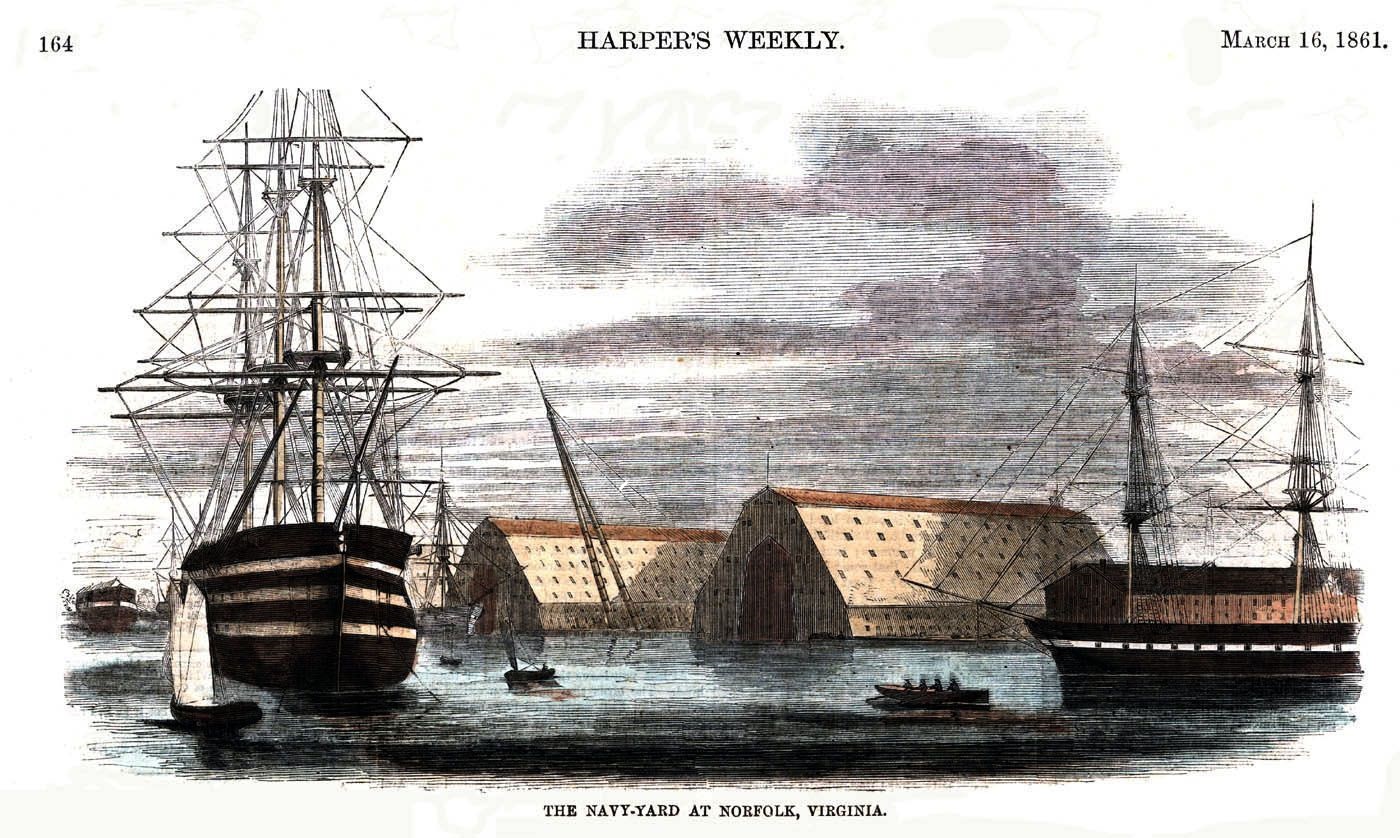

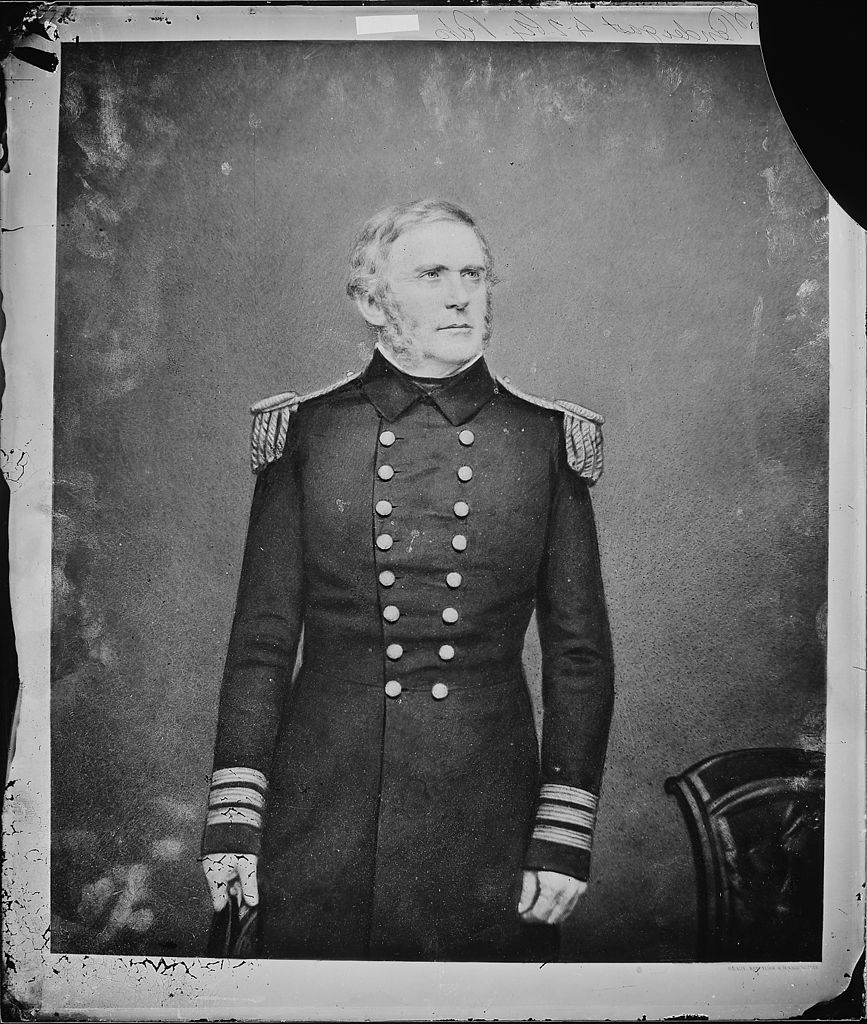

The crisis at Gosport had reached its zenith by the morning of April 20, 1861. Flag Officer Charles Stewart McCauley appeared to have given up all hope of saving or defending Gosport Navy Yard. Early that morning, he learned that militia troops had seized Fort Norfolk and an extremely useful magazine filled more than 250,000 pounds of gunpowder. Therefore, McCauley believed he had no choice but to destroy the shipyard so that it would not fall into the hands of the Virginians.

Escape Plan

Not all among the seemingly trapped Federal forces shared McCauley’s belief that the only way out was to destroy the yard. Commander James Alden surveyed the obstructions before leaving for Washington. His assessment? They were insufficient to halt Federal ship traffic.

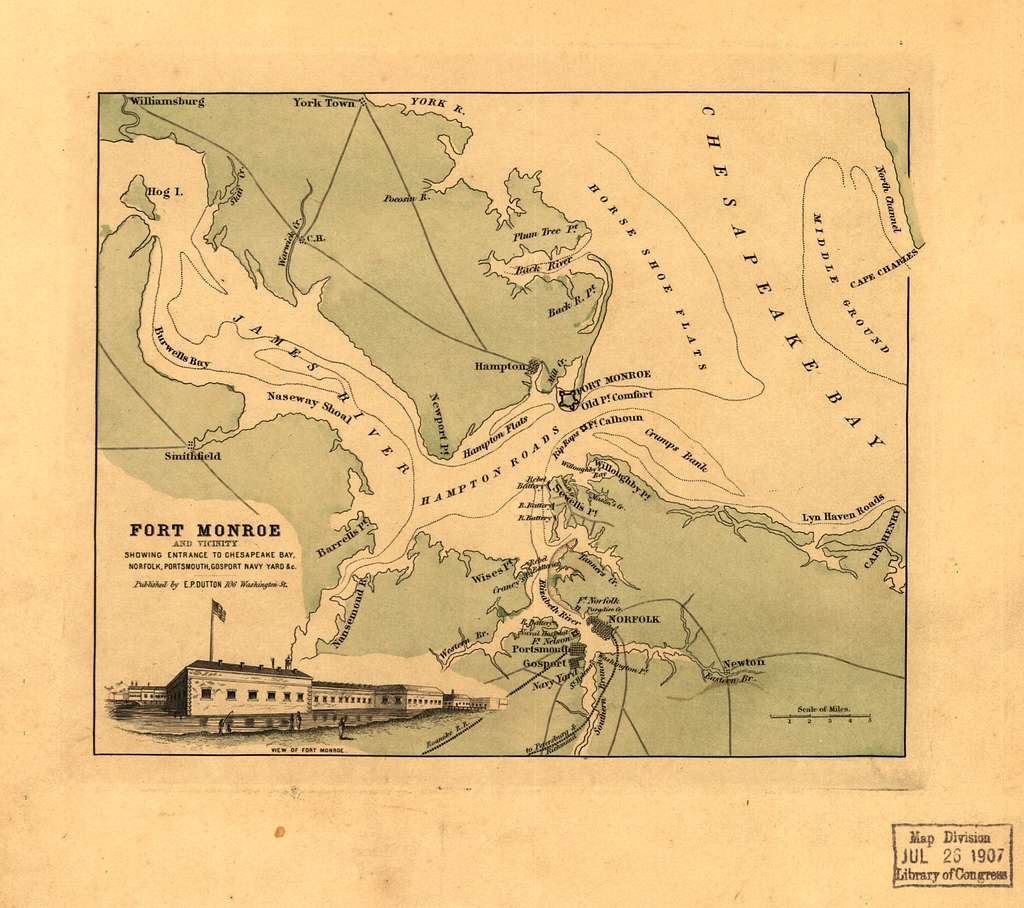

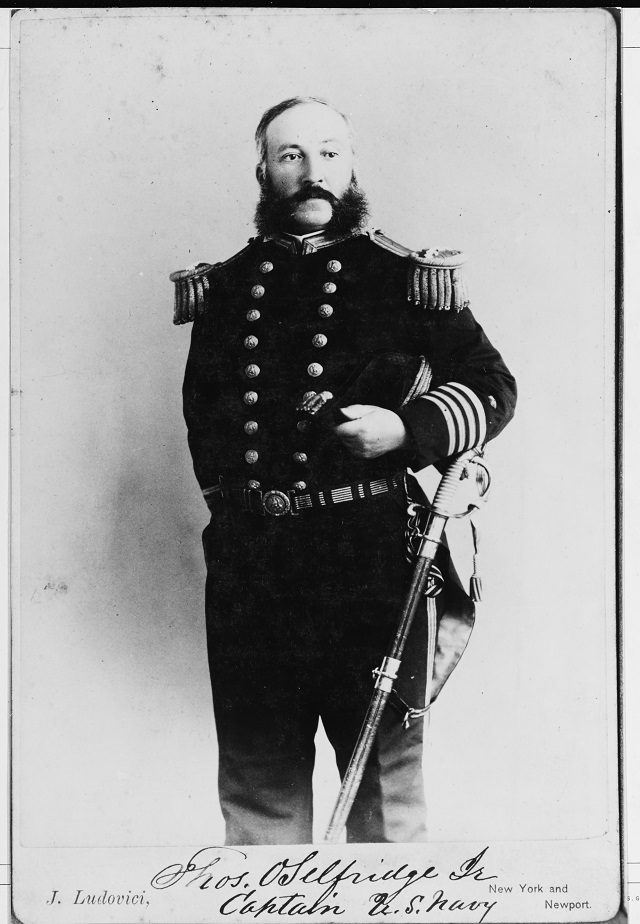

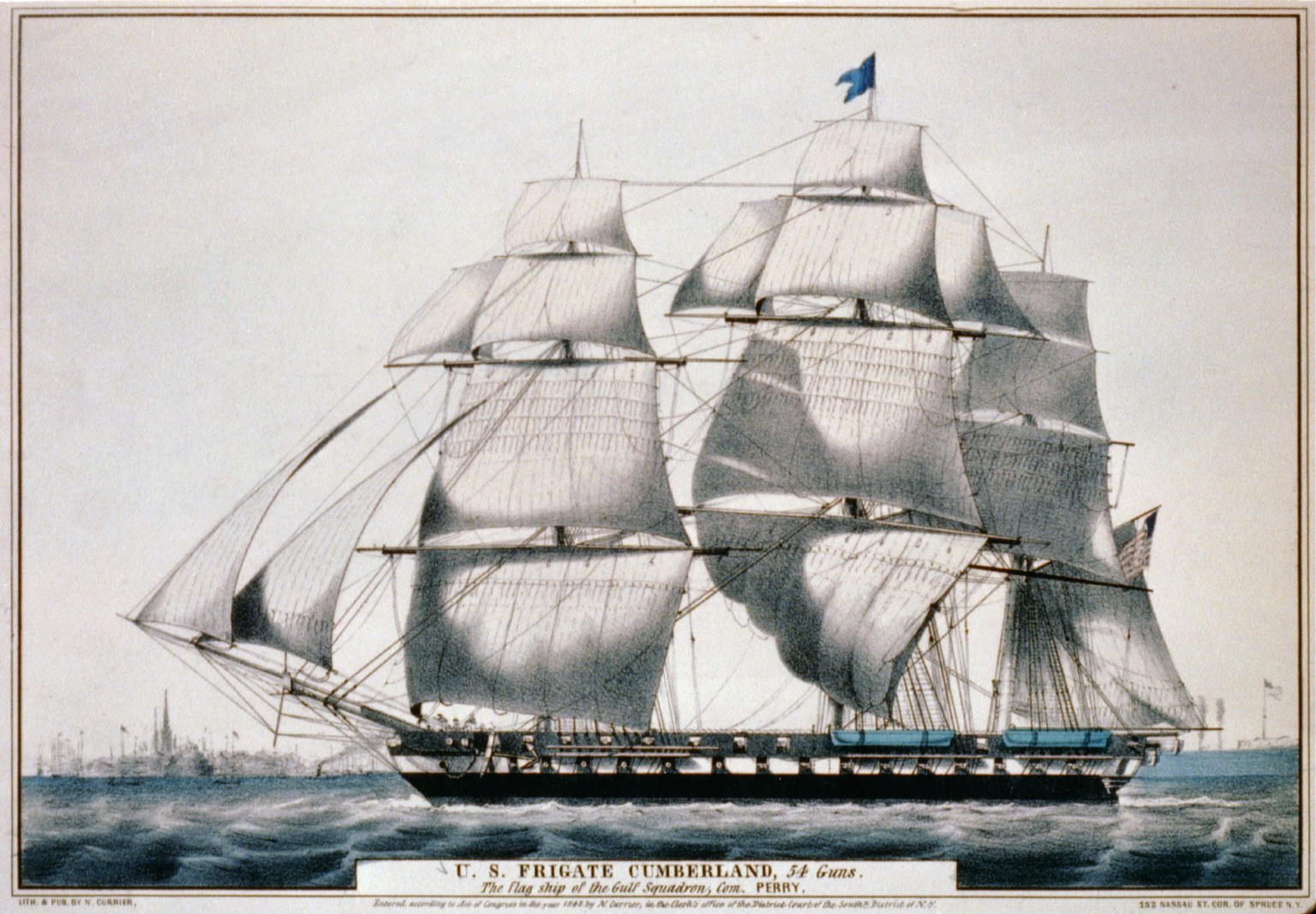

Lieutenant Thomas O. Selfridge of USS Cumberland went to Norfolk under a flag of truce to learn about the Southern batteries. He met with Captain Robert B. Pegram and then Captain Henry Heth. But he could not glean any information about militia preparations to storm or shell the yard. Selfridge then climbed to the top of Cumberland’s mainmast where he observed there were no batteries threatening Gosport.

The ship’s commander, Garrett Pendergrast, thought that many resources could be saved and that using the tug USS Yankee would allow an escape.

Gosport, Given to Flames

Saturday, April 20, 1861, dawned as another tense day along the Elizabeth River. McCauley saw danger everywhere. The capture of Fort Norfolk’s arsenal the previous evening only added to the pressure exerted by Taliaferro’s militia and angry citizens. The yard was in complete disorder. “The men were standing in grounds about the Yard,” remembered Navy Constructor John L. Porter, and “no one could work.”

McCauley, believing his command was surrounded with no relief in sight, made the fateful decision to abandon Gosport Navy Yard. At noon, he dismissed the workers and ordered the gates locked, and marines and sailors to scuttle ships and destroy property that could not be removed.

Angry Citizens Collaborate

Residents were in an uproar over the events that were unfolding before them. Rumors spread throughout Portsmouth and Norfolk that the “authorities of the Yard were making preparations to destroy that establishment with fire.” William Peters and William Spooner, both former shipyard employees, hired a boat and sailed to the yard to investigate. What they saw shocked them beyond belief: sailors had already begun scuttling ships. Observing the once-proud vessels burning and fearing that efforts to burn the yard might result in the fire spreading into town, the men returned to Portsmouth.

They hastily organized a town meeting; and a Citizens Committee was established to entreat McCauley not to burn Gosport. The committee was met at the yard’s gates by Brigadier General George Blow of the Virginia Militia and two former officers of USS Cumberland, Lieutenant John Maury and Paymaster John De Bree. Maury and De Bree, who had just resigned their US Navy commissions, advised the Citizens Committee that McCauley refused to meet with anyone on the subject.

While the Citizens Committee was rebuffed in its effort to dissuade McCauley from burning the yard, others took a more active approach. One group of firebrands tried to capture the tiny side-wheel steamer tug Yankee, which had been commandeered by Pendergrast to move Cumberland out of the Elizabeth River. The attempt failed, according to Private Daniel O’Connor of the sloop’s Marine Guard, because when “they seized her…they let her go very quickly when we pointed our pivot gun at her.” O’Connor remembered the rejected firebrands yelling “of massacring the whole of us or taking the navy yard that night and shipping but we intended to sell our lives as dearly as possible.”

Thomas O. Selfridge also remembered a little more humorous incident. One particular steamer filled with rebels continued to hover near the yard shouting threats and abusive language at the loyal workmen who were destroying the yard. Selfridge and members of Cumberland’s crew rigged an underwater line from the yard to a tug on the other side of the channel. When the rebel tug approached the yard for another round of abuse, the hawser line was pulled taut, raking the entire length of the tug, knocking the vessel’s smokestack off, pushing several men overboard. After this episode, there were no other attempts to approach the yard by the Elizabeth River.

Duties of Destruction

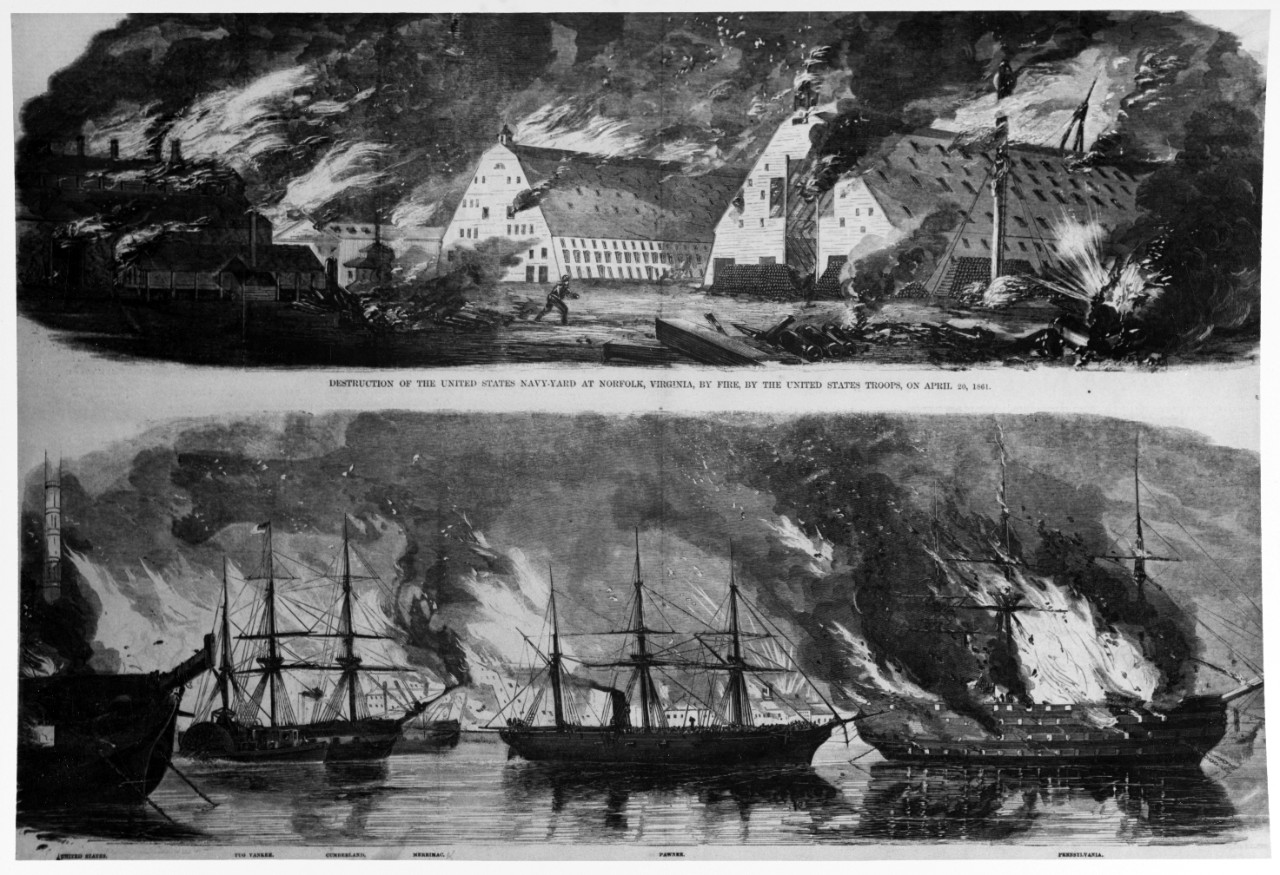

As the Virginia Militia and local citizens watched in disbelief, McCauley’s men went on with their duties of destruction. All the major warships in the harbor, except Cumberland and the venerable United States, were scuttled by mid-afternoon. Anchored out in the river were Columbia, Pennsylvania, and Raritan. All were set on fire and burned almost down to their keels. Germantown’s rigging was cut away, causing the shears to fall across the sloop and sink.

The scuttling was not as effective on most of the other ships. Due to the Elizabeth River’s depth, many of larger ships, such as Delaware and Columbus, did not totally submerge. Crews simultaneously loaded Cumberland with gunpowder, some small arms, and other supplies. Any small arms that could not be saved were thrown into the river. An effort was made to render the 1,085 modern heavy cannons stored at the yard useless. Teams of men armed with sledgehammers attempted to break off the trunnions of cannons, but this proved to be a difficult, time-consuming, and virtually impossible task.

Paulding Arrives – Hours Late Fire

Meanwhile, Flag Officer Hiram Paulding’s task force reached Fort Monroe on the afternoon of April 20. Paulding embarked 350 men of the 3rd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment on board Pawnee and steamed toward Norfolk. The task force arrived at Gosport about 8 p.m., but Paulding realized that it was too late. Ships were already sinking, and the yard appeared to be in complete confusion.

Paulding, who had seniority over the yard’s commandant, assumed command from a demoralized McCauley. He quickly recognized that there was little else he could do other than finish the job. Elements of the 3rd Massachusetts guarded the yard’s outer walls so the angry mob outside the gate would not disrupt the work of the demolition crews. As an extra precaution, Cumberland and Pawnee were anchored in the Elizabeth River to enable their cannons to rake any approaches to the yard. The local Southern volunteers could only observe from afar the flames’ destructive work.

Once Paulding asserted his command, Union crews immediately went forward with their assigned demolition tasks. Paulding had stocked Pawnee with a wide variety of combustibles including: 40 barrels of gunpowder, 11 tanks of turpentine, 12 barrels of cotton waste, and 181 flares, all meant to destroy the yard.

Fire on the River

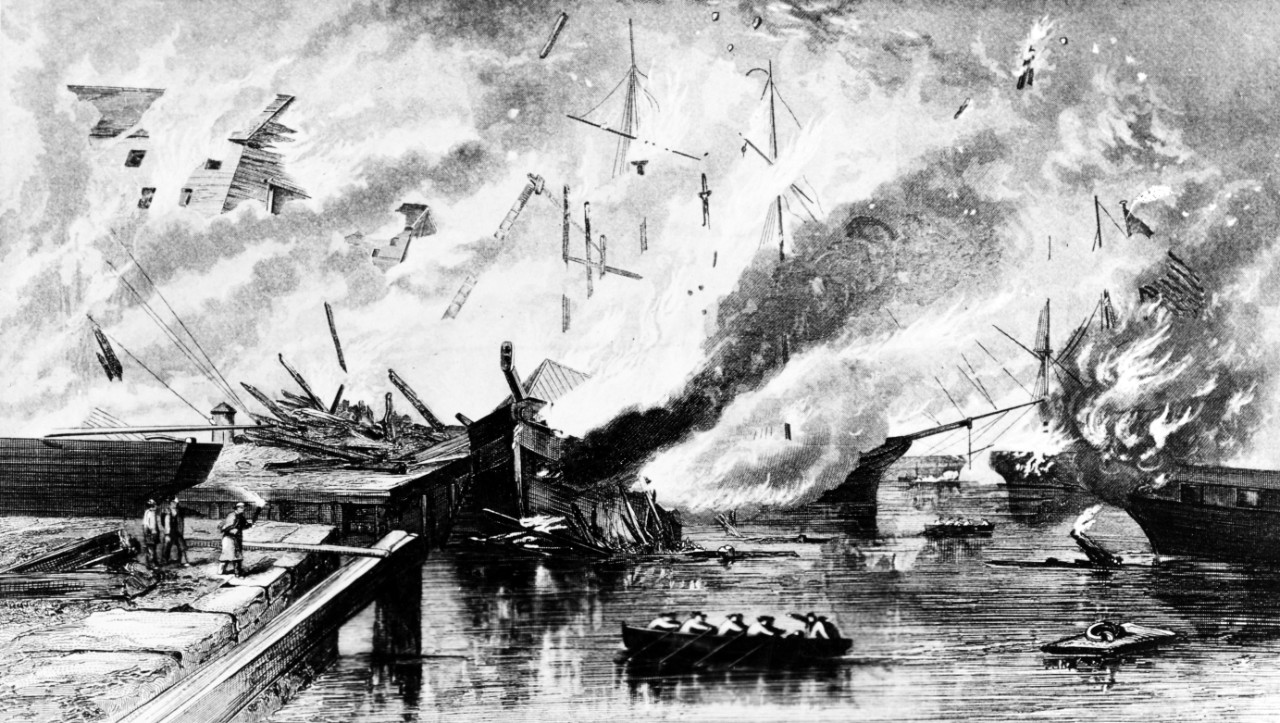

The mighty 120-gun Pennsylvania, now engulfed in a sheet of flames, dominated the eerie scene. No one had unloaded the ship’s cannons, so the night was filled with occasional blasts from the four-decker’s guns. All the ships in the harbor were set ablaze with determination to leave nothing of use. Merrimack was torched by Lieutenant Henry A. Wise, who watched as the flames “were belching from her lower decks, with her upper works, masts, and rigging burning at the same time.”

As ships like Raritan burned in the harbor, buildings throughout the yard were set on fire. The two huge ship houses, A and B, were quickly engulfed by flames. Ship House A contained the partially completed 74-gun New York, which was consumed by fire as it sat on the stocks. Since everything would not burn, sailors and marines rushed through the yard laying powder trains to destroy valuable machinery and facilities. When efforts to break off the trunnions of cannons proved futile, the 1,085 guns were spiked. Two officers, Commander John Rodgers and Captain Horatio Gouverneur Wright, were assigned the critical task of mining the granite dry dock. Their work was purportedly foiled by a petty officer who did not wish the explosion to damage the nearby homes of his prewar friends.

At 4:20 a.m., following the burning of the marine barracks, Pauling ordered his men to the ships. The tide was rising and everything that could be done to destroy the yard’s military value had been done. McCauley, in tears, had to be escorted onto Cumberland by his son. The commandant had wished to be left behind like Nero and be consumed by the fire. As the early morning sky turned bright with the flames, Pawnee steamed out of Gosport, followed by Yankee, with Cumberland in tow. The flames could be seen 30 miles away.

The Yard is Lost

The small Union flotilla slowly made its way down the Elizabeth River. The Federal ships crossed the obstructions sunk in the channel before dawn. “We were dragged over the obstructions,” remembered Lt. Selfridge, and “anchored off Fort Monroe.” Cumberland immediately became the nucleus of the Federal squadron blocking Hampton Roads and the lower Chesapeake Bay.

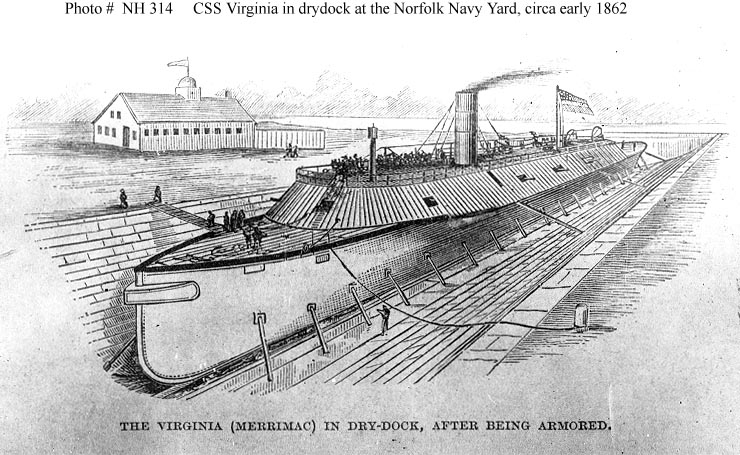

The entire operation was over by 6:15 a.m., and despite the loss of Gosport and Merrimack, was considered a success by Gideon Welles. The Confederates, however, were equally pleased with the events of April 20 and 21,1861, having gained in a single evening, one of the finest shipyards in America. The yard soon would be the site where the Confederates transformed the burnt and sunken USS Merrimack into the powerful ironclad ram CSS Virginia.

This is part three of a four-part series about Gosport Navy Yard by John Quarstein. “The Recapture of Gosport” follows.

Excerpted from CSS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012. Available in the Museum’s Web Shop: https://www.google.com/url?q=https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/sink-before-surrender-pb.html&sa=D&source=hangouts&ust=1587055613966000&usg=AFQjCNGlDlDHoLEWTXRLO71bPBmtARqV5A