Although 2020’s pandemic has not been a good thing for museums there are some museum professionals who are reaping big rewards from being stuck at home. Who are these lucky people? The curators, archivists and collections staff responsible for cataloging objects because finally, FINALLY, there is plenty of time available to review, expand or correct the cataloging of the objects and images in their collections.

Cataloging is the process of researching and recording detailed information about an object. This process is completed when an object initially enters a museum’s collection but at Mariners it’s pretty obvious that the curators and collections staff didn’t always invest the kind of time necessary to fully and accurately research the objects they were cataloging. The result is misidentifications, misattributions and sometimes a complete lack of information beyond an object’s name or title!

Since the museum closed on March 16th the staff in our Collections Management department have been trying to rectify our cataloging deficiencies and so far, just two of us have managed to correct, expand, or completely recatalog more than 500 items. For my part, I have been cataloging Iñupiat (Eskimo) cultural materials and one of the toughest types of object to research–engravings from 16th and 17th century atlases and books. The cataloging of these images nearly always requires some seriously intense detective work to accurately understand the image’s origin or the scene’s history.

[For those of you who have made it this far and have already decided “PFFT! It can’t be as hard as she says!” hang tight. There’s a test at the end of this post to see if YOU think one of our engravings has the correct attribution.]

Now I know what you’re thinking–if you’re just talking about a page pulled from a book why can’t you just find the book and write the information down? Well sometimes it is that easy and you find the book you’re looking for the first time, the other 99% of the time you’re not that lucky. “Why?” you ask? It’s because we’re talking about the 16th and 17th century book publishing business and the rules that governed it.

Copyright? What’s that?

Plagiarism? Huh?

Intellectual Property Rights? I don’t understand what you’re talking about.

Rules! Schmules!

- Publishers used the same images to illustrate different stories in the same book

- They used the same images to illustrate multiple books

- Printing plates were inherited or sold and then used to illustrate even more books

- People rampantly copied images and used them in their own publications.

- Sometimes after copying someone else’s plate they would change the image or add information to the printing plate creating a similar, but essentially different image (at least when it comes to cataloging!)

- Books were translated into many different languages but the images remained the same

So what does this mean? It means you might have to search through 2, 3 or sometimes 20 publications before you find exactly which book an image was pulled from. Doing this sort of research from the comfort of your own home would have been impossible just ten or twenty years ago. These days we have access to thousands of digital versions of historic publications online through organizations like Google Books, Archive.org, Hathi Trust, libraries, universities and even private collectors (like the David Rumsey Map Collection).

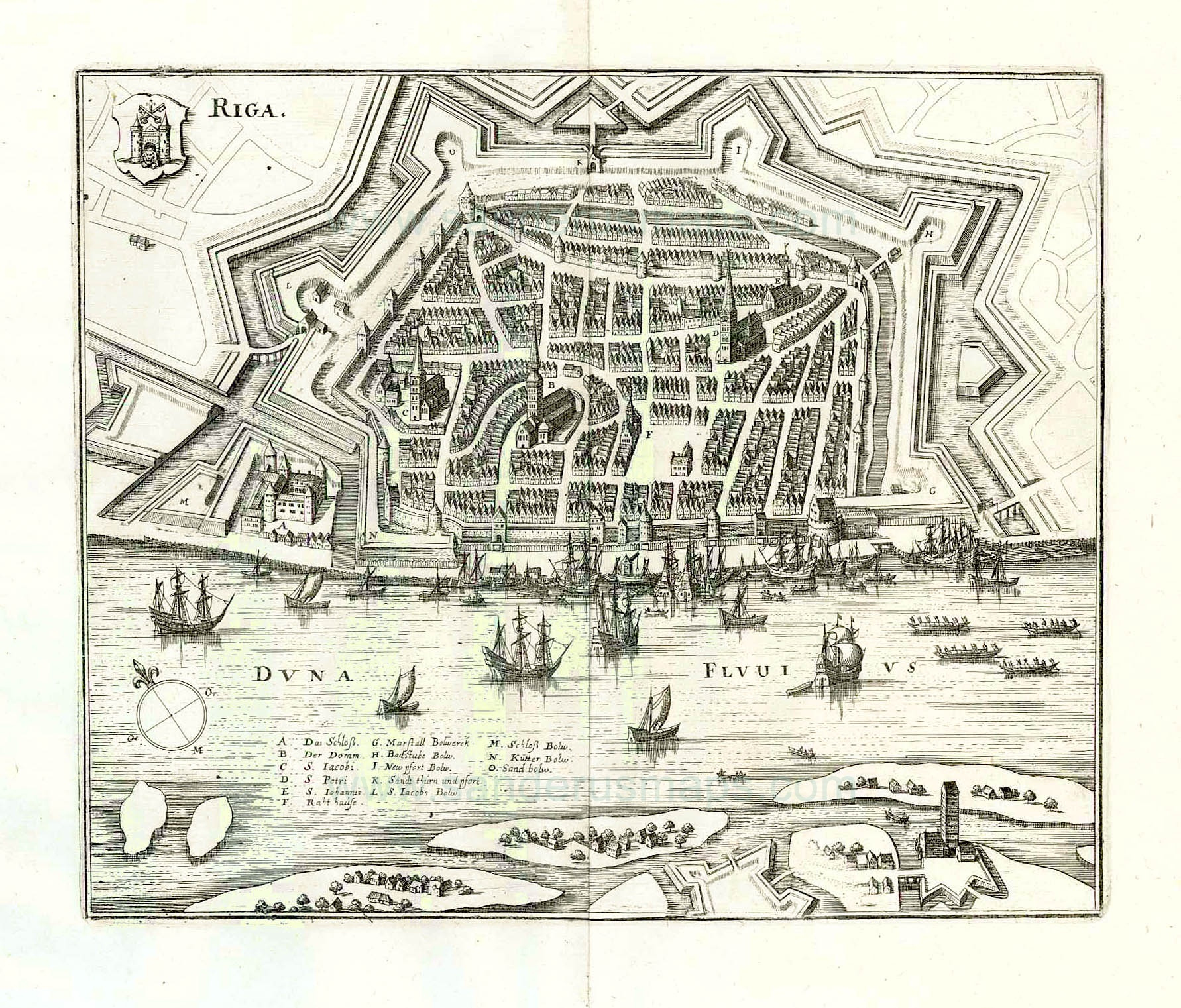

Here’s just one example of the tangle I ran into when I tried to catalog a 17th century map engraving in our collection. This is a bird’s-eye view of the town of Riga in Latvia. If you look carefully you’ll see there are no words or marks other than the name of the town.

A former curator suggested the Riga image may have come from an atlas published by Pierre D’Avity so that’s where I started my search. D’Avity published an atlas in the 17th century that was so popular nearly thirty editions were printed in French, German, Latin and English between 1613 and 1695. Interestingly, the only edition where I found an image of Riga was the 1646 German edition.*

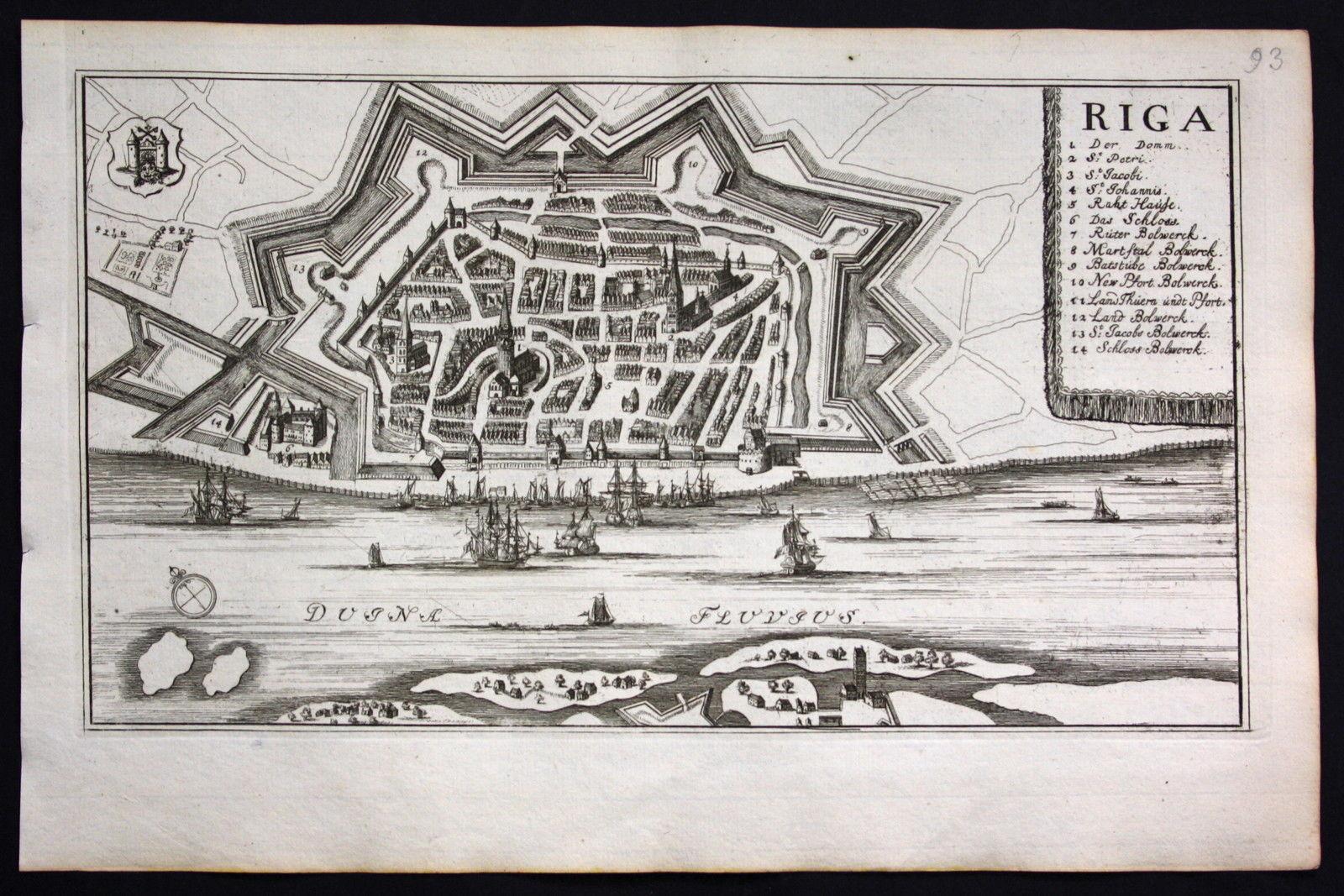

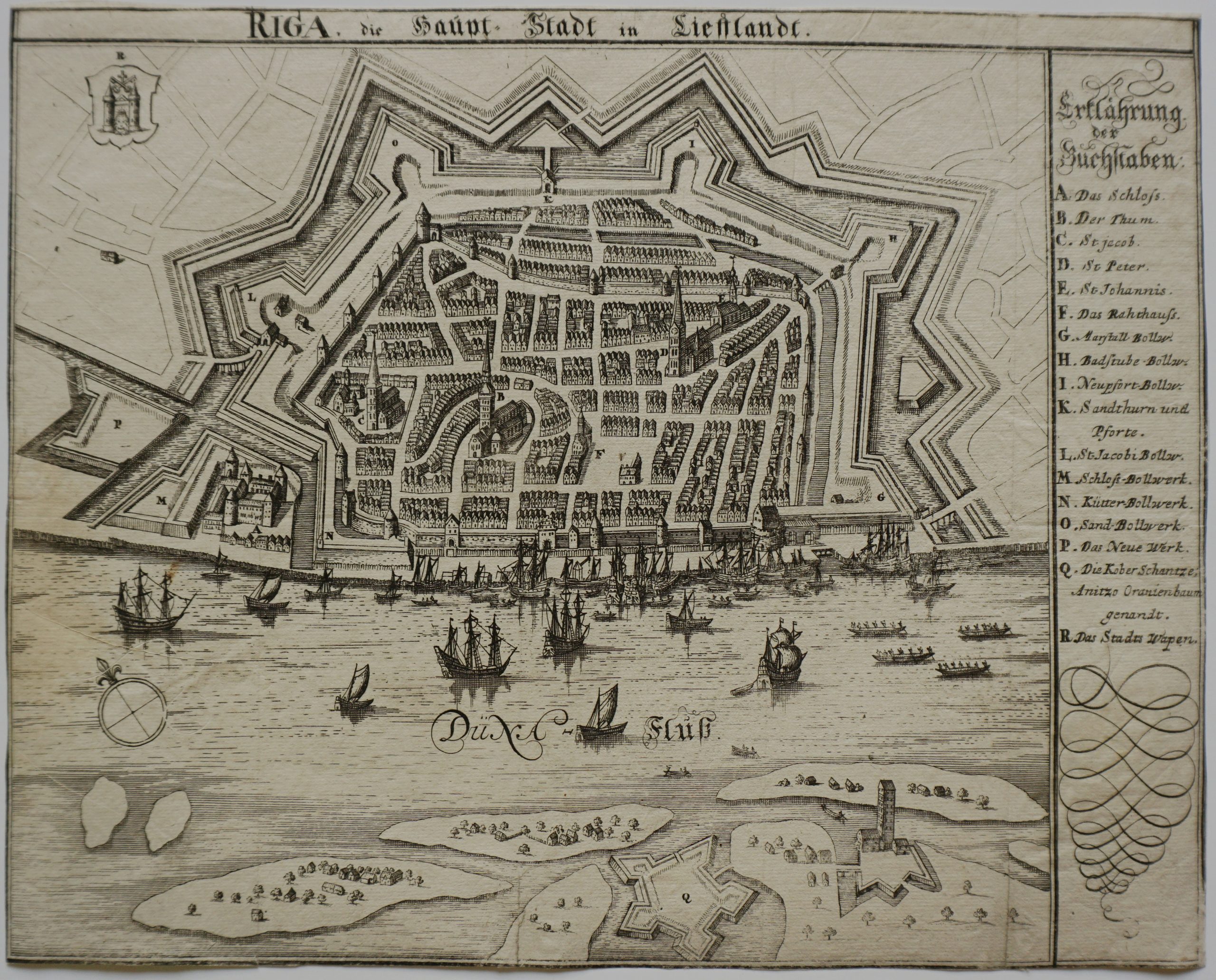

I found this same image in J. Angelius von Werdenhagen’s ‘De Rebus Publicis Hanseaticis,’ published in 1641 (the earliest view I found); in Matthäus Merian and Martin Zeiler’s ‘Topographia Electoratus Brandenburgici et Ducatus Pomeraniae,’ published in 1652; and in the 1707 ‘Theatrum Europaeum.’ However, the image differs from ours in that it includes the name of the river and has a numbered key for structures within the city. With the D’Avity publication (and three others!) ruled out I continued my search.

The next image of Riga I found was in Adam Olearius’ 1727 ‘Voyages très-curieux et très-renommez faits en Moscovie, Tartarie et Perse…’. It’s closer! But it’s still not an exact match (unlike our image the Duagava River is clearly marked).

And another!

I never did find the German publication the image below came from.

And finally this image from Pieter Van der Aa’s 1730 ‘La Galerie Agreeable du Monde.’ Still not a match. At this point (three days after I started my search!) I gave up and figured I’d do some more digging later. I have about three hundred other images to catalog so I hoped I’d get lucky and stumble across the image of Riga while working on something else.

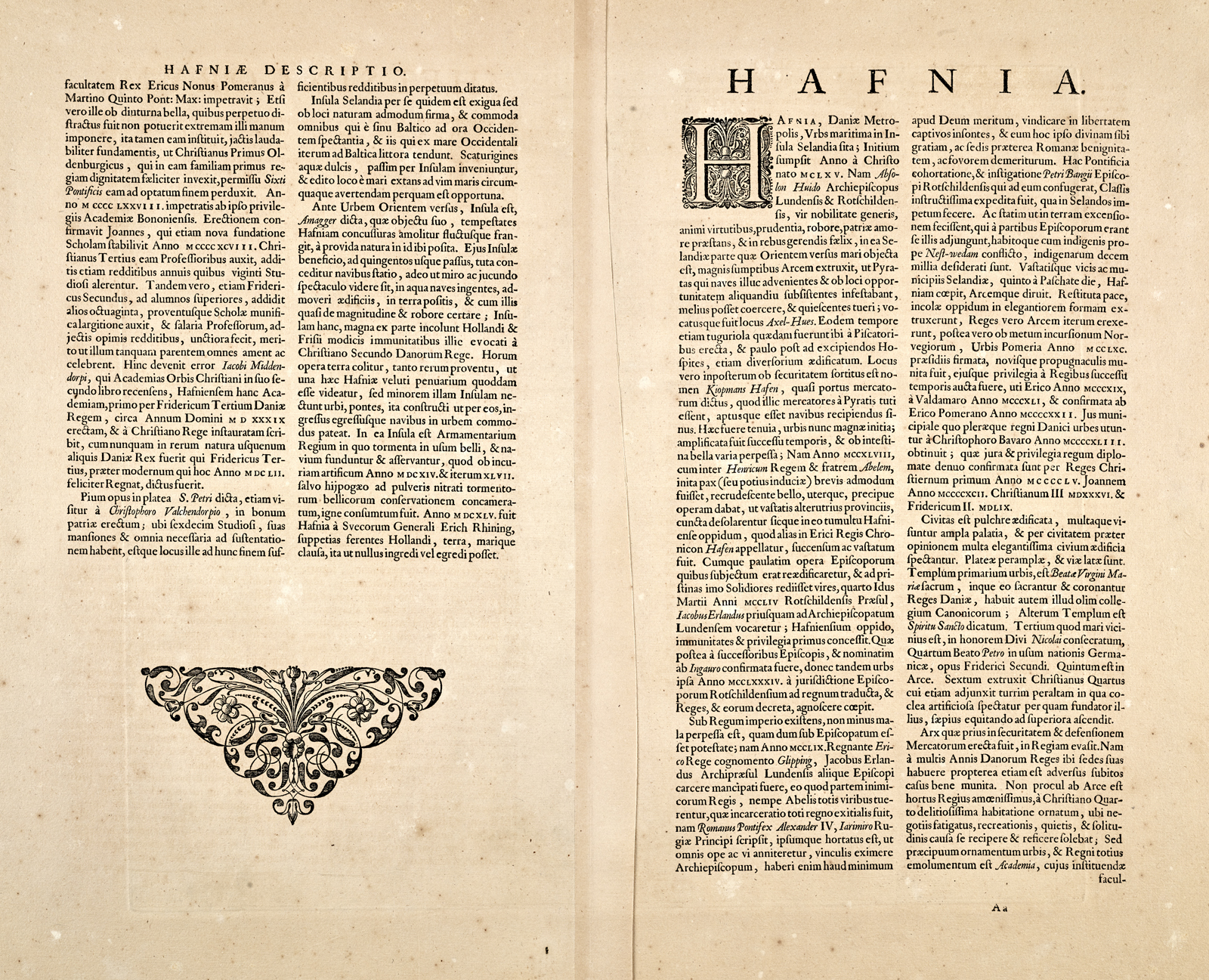

The next thing I decided to work on were a number of images a former assistant curator had attributed to Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg’s famous six-volume set of town atlases called Civitates Orbis Terrarum (published between 1572 and 1617). She attributed them to Braun’s work after looking at “A List of Geographical Atlases in the Library of Congress,” one of the leading research resources for atlases. However, a visual comparison of the reverse sides of our engravings with those in Civitates clearly shows that our images came from a different publication. While looking at the back might not always help (if it’s blank) if it contains text you can use the language and formatting to pin it to a particular edition of a publication.

Here’s an example. Looking at the front (also called the ‘obverse’) of our engraving titled “Hafnia vulgo Kopenhagen” you’ll see that it is identical (except for the hand-coloring) to the image found in Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum.

But when you compare the backs it’s obvious the images came from different publications:

Using my detective skills, I discovered that the formatting of the text on the back of our view of ‘Hafnia vulgo Kopenhagen’ matched a number of other engravings in our collection which made me wonder if they had all come from the same publication. Most of the images had been cataloged to Civitates–but not all them! For three of the images someone had postulated that the image may have come from one of the eight town atlases published by Johannes Janssonius in the mid-17th century. Janssonius had purchased 363 plates from the Braun and Hogenberg heirs and used 232 of them plus 173 newly-engraved plates to create his own publication–which is why people who don’t pay careful attention attribute their engravings to the wrong publication!

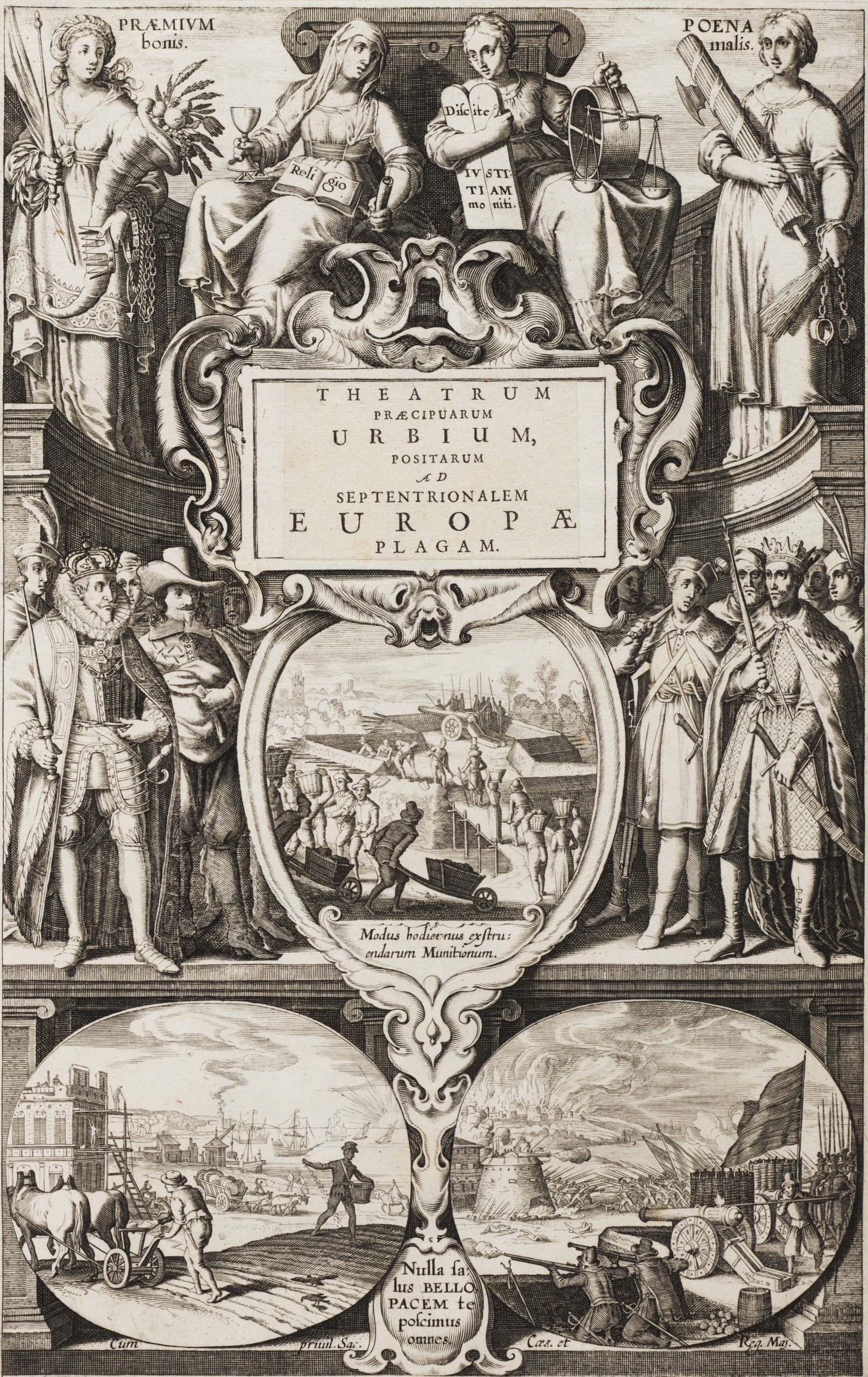

Luckily, I was able to find four of Janssonius’s town-atlas digitized in the online collections of the Allard Pierson museum of the University of Amsterdam. Thanks to this wonderful online resource I was able to determine that twenty-six engravings in our collection actually came from the Janssonius publications and not Braun and Hogenbergs. And the best news of all? Smack dab in the middle of Janssonius’s ‘Theatrum praecipuarum urbium, positarum ad septentrionalem Europae plagam’ (volume 3) was the view of Riga I had spent days searching for!

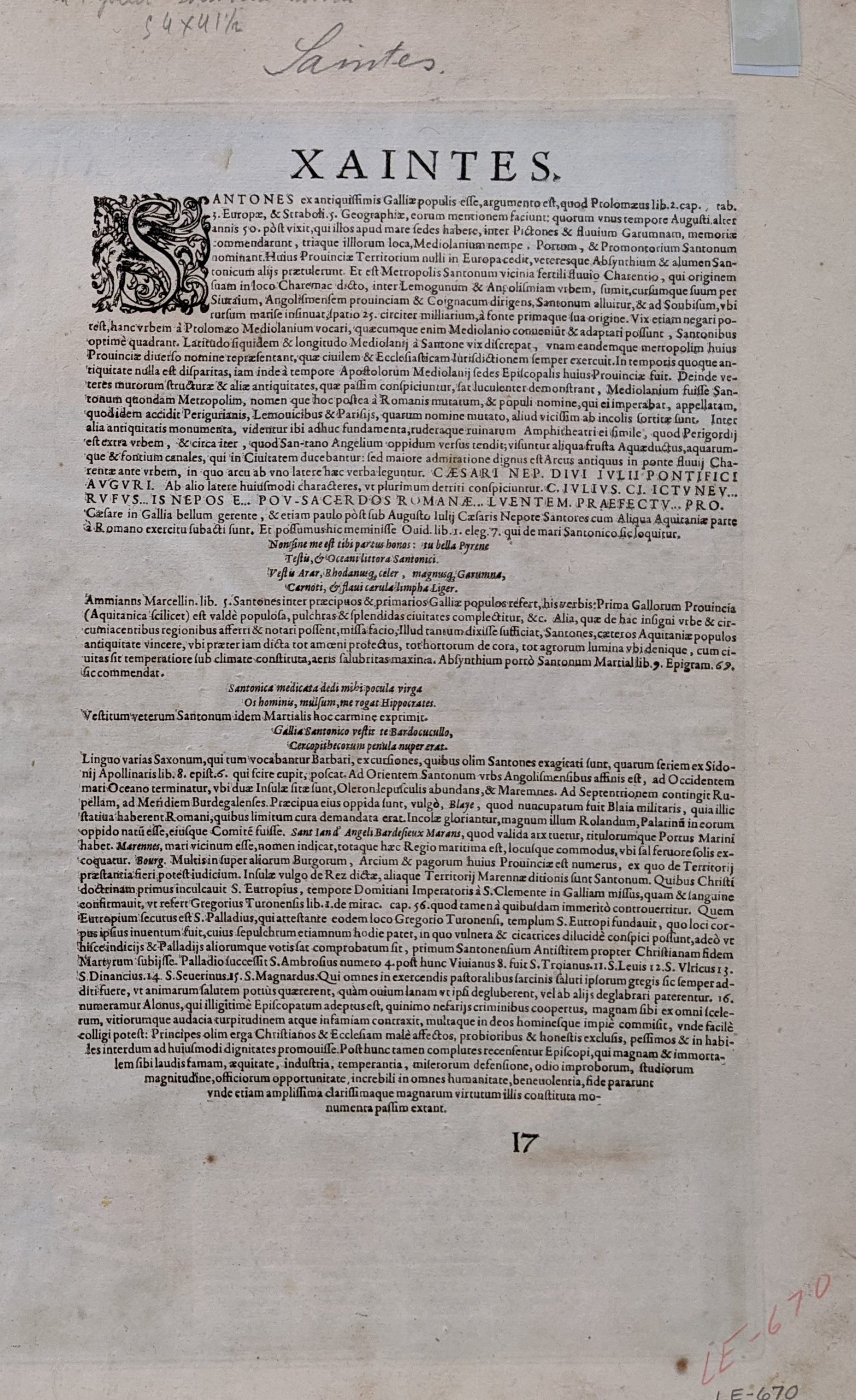

So now that you have an idea of how difficult it can be to correctly catalog an engraving from a 16th or 17th century publication let’s take a test. Here are images of the front and back of our engraving of Saintes, a town western France. It is currently attributed to volume 5 of Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum (the title of volume 5 is ‘Urbium praecipuarum mundi theatrum quintum’). Of the three links I’ve provided below, can you guess which edition most closely matches our engraving?????

Here is a link to the Universiteit Utrecht’s 1617 edition of Volume 5.

Here is a link to the Library of Congress’s 1612 edition of Volume 5.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3200m.gct00128c/?sp=40&r=-0.424,-0.067,1.839,0.812,0

Here is a link to the Bayerische StaatsBibliothek’s circa 1640 edition of Volume 5.

*This may be attributed to the fact that for some reason many digital publications do not show the images that accompany the text. They are either shown as closed or partially opened plates. While I searched carefully it’s entirely possible I just couldn’t see the Riga image even though it was present.