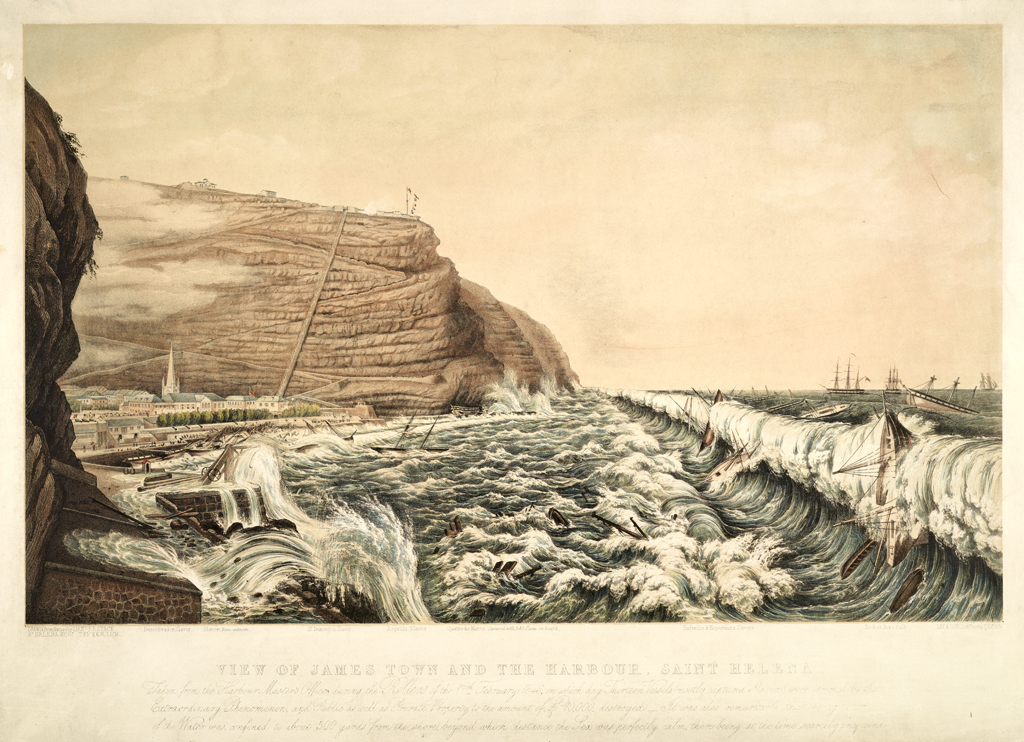

It’s time for me to admit something—I have a sick fascination with historical disasters—especially those related to natural phenomena. I don’t know why. I just do. Some of the prints and engravings we have in the collection are really unique so I thought I would share one of my favorites: The February 1846 “rollers” at St. Helena. This image has fascinated me for years! The first time I saw it my immediate question was—what the hell are “rollers.” Now obviously they are waves but why did these particular waves deserve a different designation? (And no, they are not related to an earthquake or tsunami.)

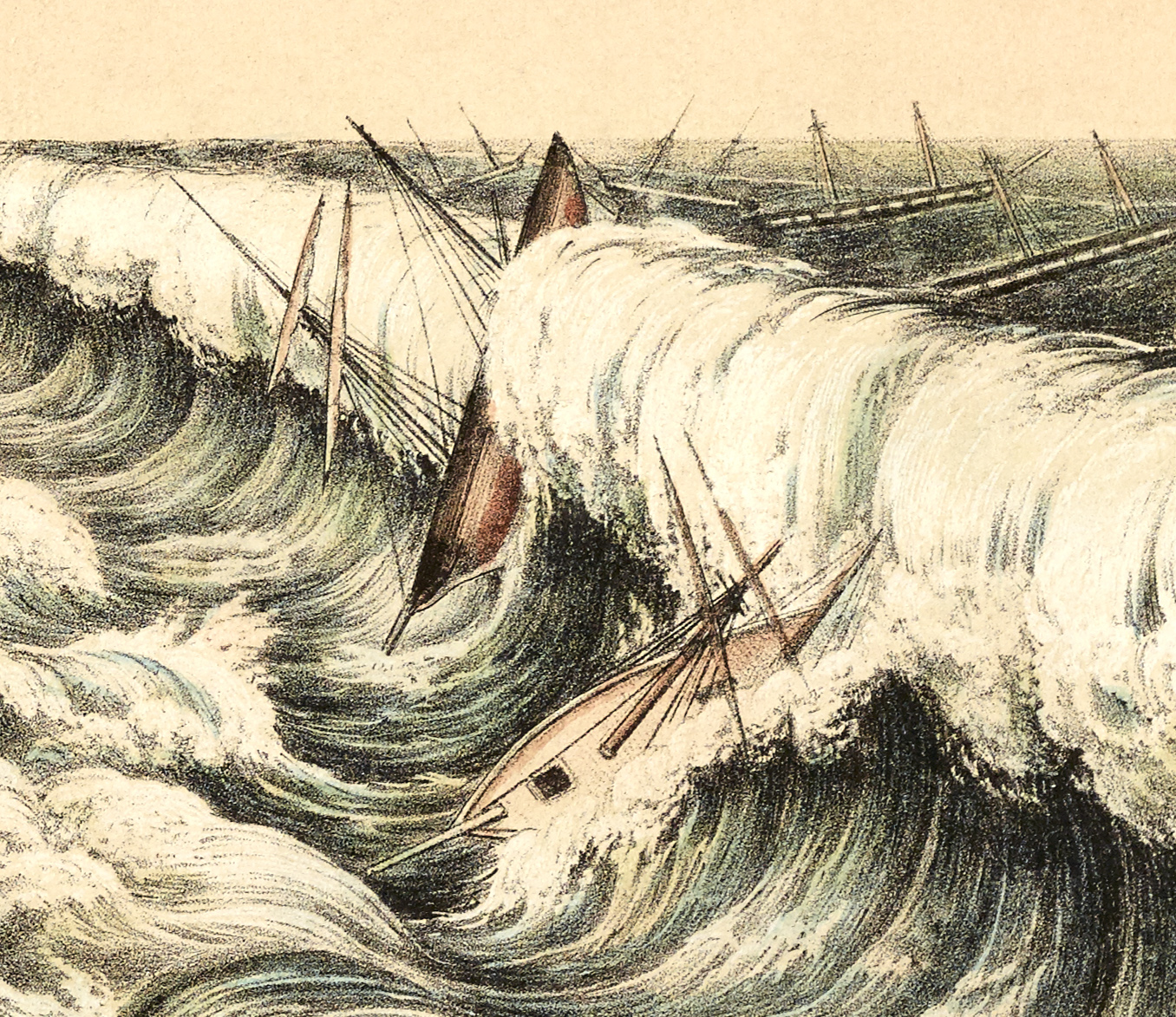

The islands of Ascension and St. Helena (the island where Napoleon was exiled) in the South Atlantic are periodically plagued by waves that seem to occur for no readily apparent reason–one moment the seas are calm, little waves start rolling ashore and before long waves big enough to surf are hitting the north facing side of the island. One source described the waves as “the rollers for which St. Helena has ever been celebrated.” Really? I find it hard to believe anybody was celebrating after looking at this image because in this instance the consequences of the “rollers” were so catastrophic the event was recorded for posterity.

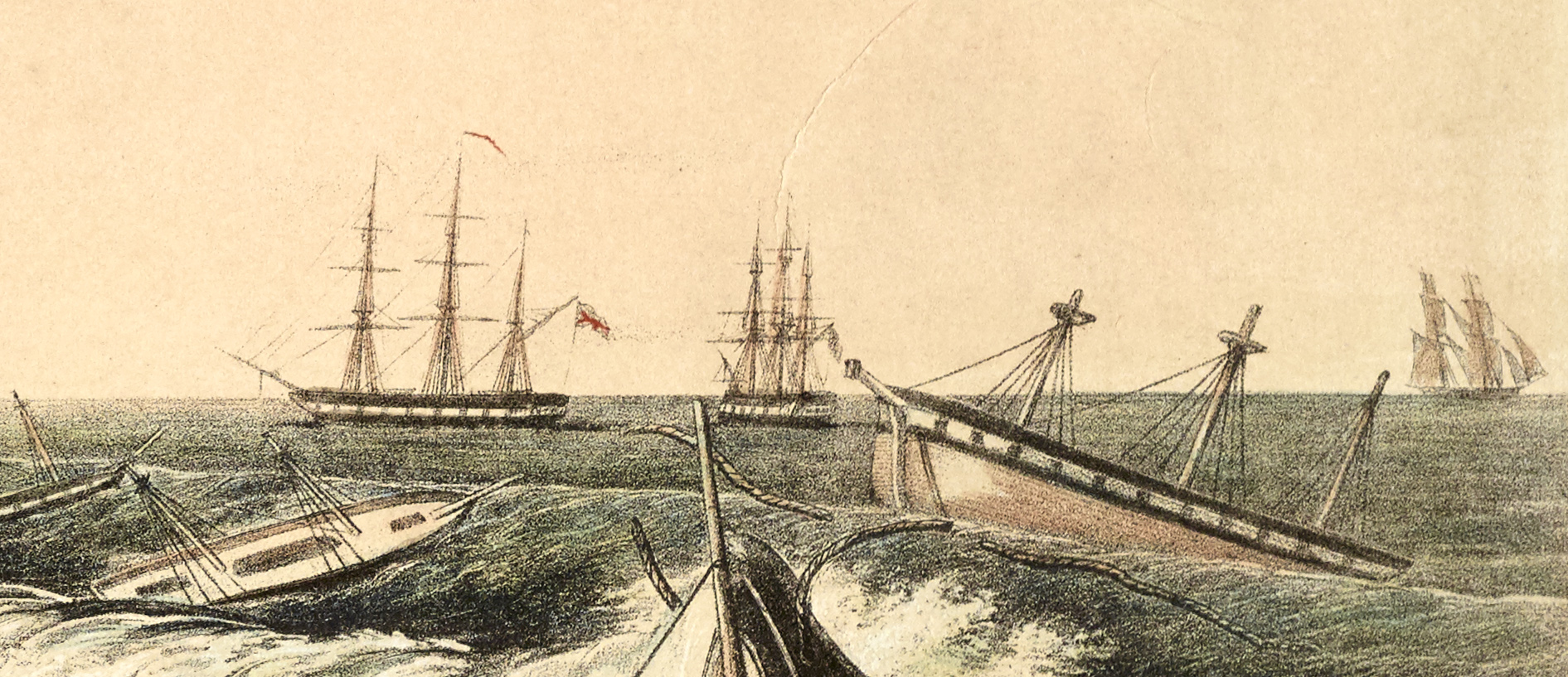

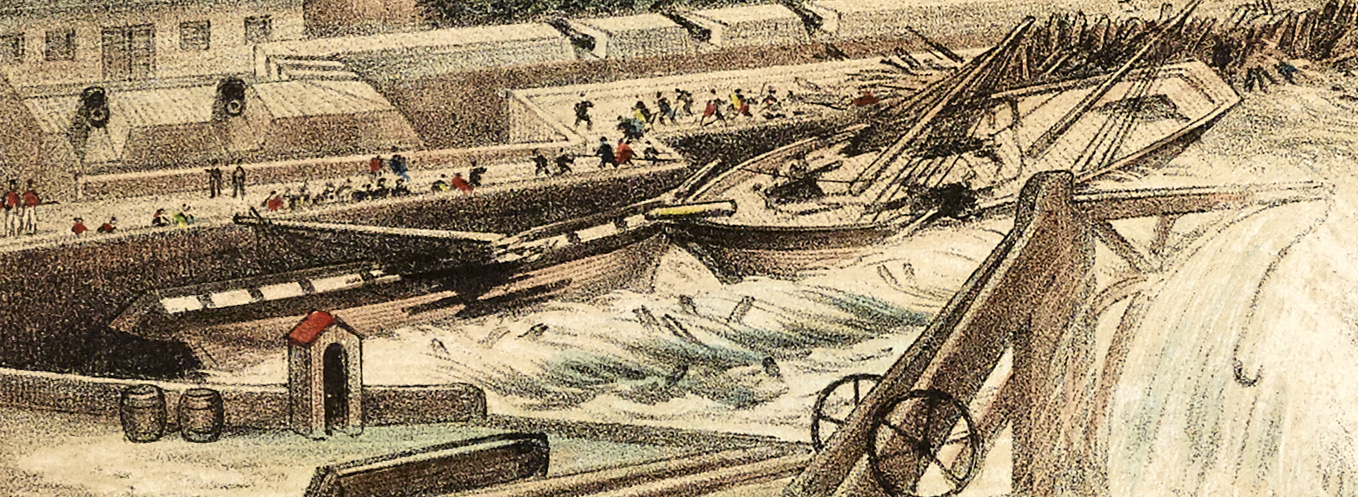

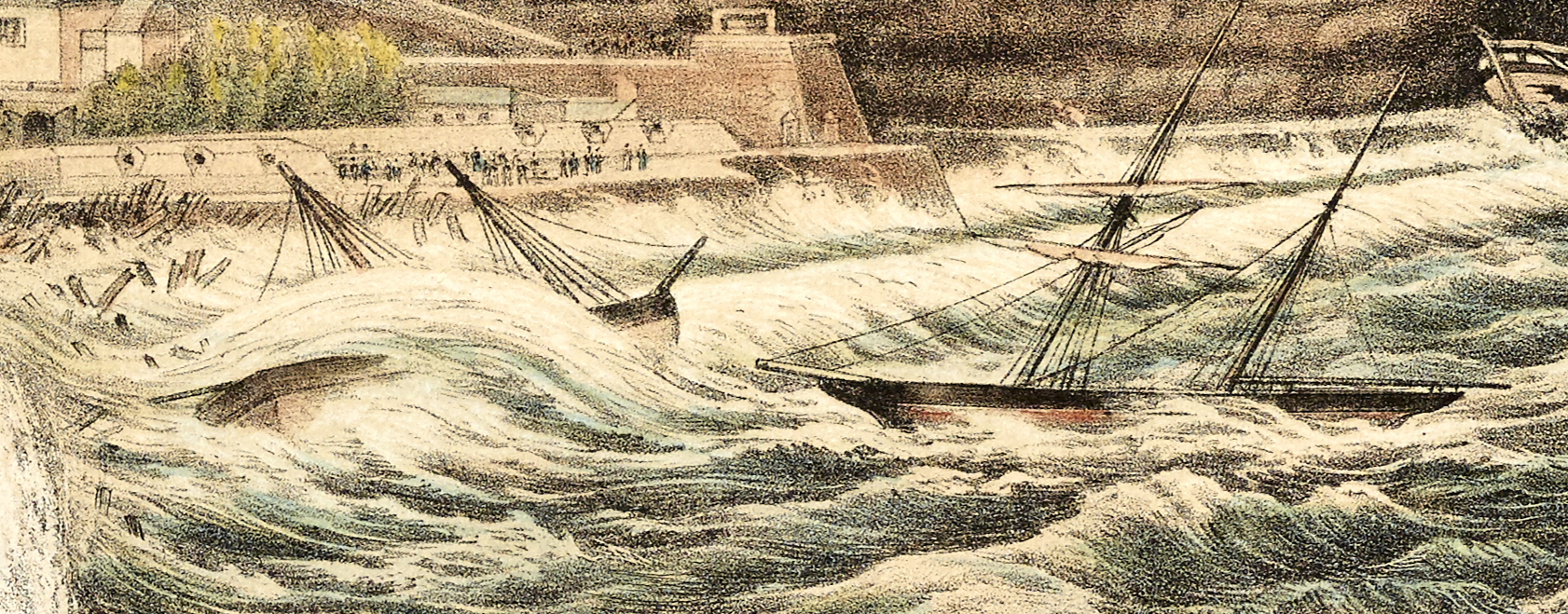

At the time of this particular roller event, February 17th, 1846, St. Helena was actively used by the British Royal Navy for the adjudication, condemnation and sale of captured slave trading vessels. So, along with the normal trading and working vessels there were eighteen condemned slave trading vessels anchored before the town. The catastrophe started, inconspicuously enough, at sunset the day before when little waves started rolling ashore even though the sea around the island was described as a “millpond.” The waves gradually increased in size and by dawn James’ Bay was described as a “mass of foam” broken only by the huge waves rolling through it. By 10:00 AM the waves had reached such a height that vessels anchored within their reach could no longer withstand them. Astoundingly, vessels anchored a mere five or six hundred yards from shore were completely unaffected.

As the waves increased in height shipkeepers aboard vessels within the “roller zone” deployed as many as four anchors in an attempt to hold their charges in place. It seems many recognized this roller event was going to be more extreme than normal so after securing their charges they headed for the safety of the ships anchored beyond the effects of the rollers (getting to shore was impossible). Those ships also provided refuge for many of the island’s fisherman who had headed to sea in the days before ignorant of the approaching disaster.

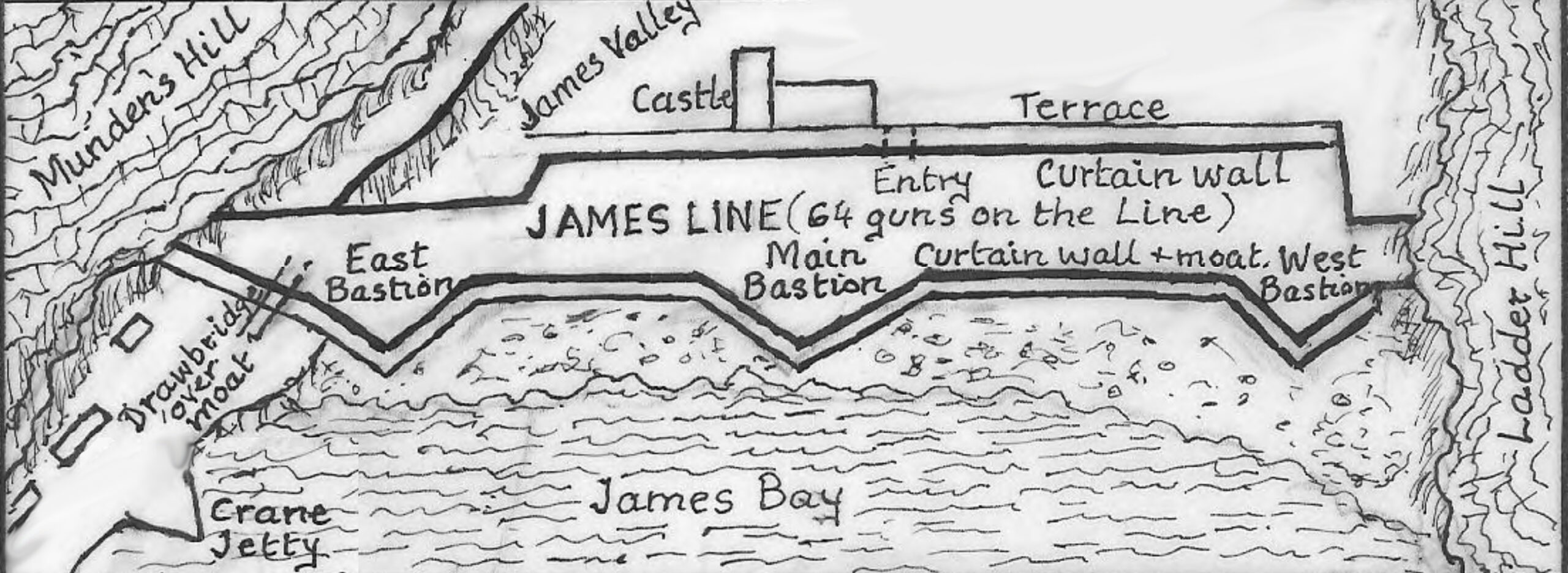

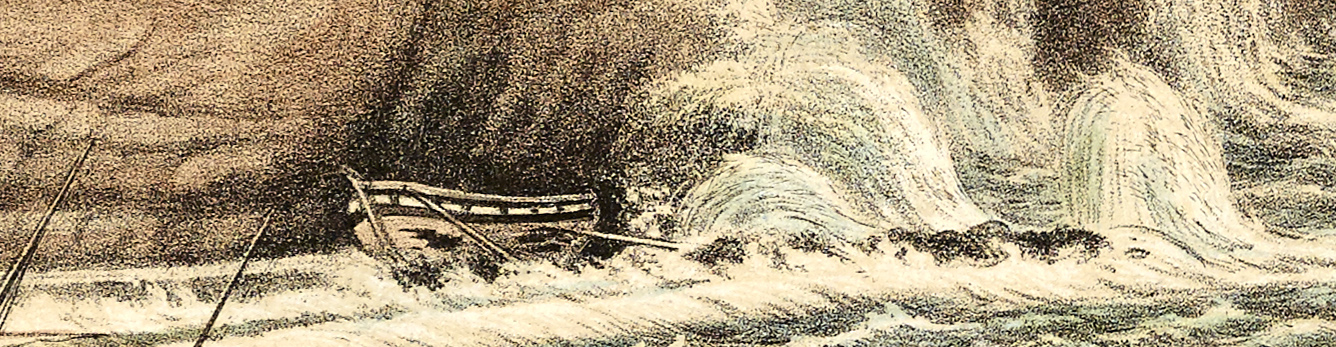

The first vessel to succumb was the English schooner Cornelia. Anchored a little farther from shore, she was completely buried by the raging waves and a little while later was thrown against the curtain wall of the James Line (the fortress that protects Jamestown). Spectators stated she became “a mass of splinters” in just a few moments. Hot on her heels was the 127-ton Brazilian brig Descobrador. Unfortunately the shipkeeper, Robert Seale, his wife Florella and two others had not managed to leave the vessel before it was driven ashore. As wave after wave crashed over the ship the shrouds gave way, the masts fell and the ship began to break apart. During a brief lull the two men jumped overboard and swam to shore leaving Seale and his wife hanging onto the rigging in the raging seas. When Seale and his wife appealed for help to those on the shore Descobrador became the scene of a desperate rescue effort.

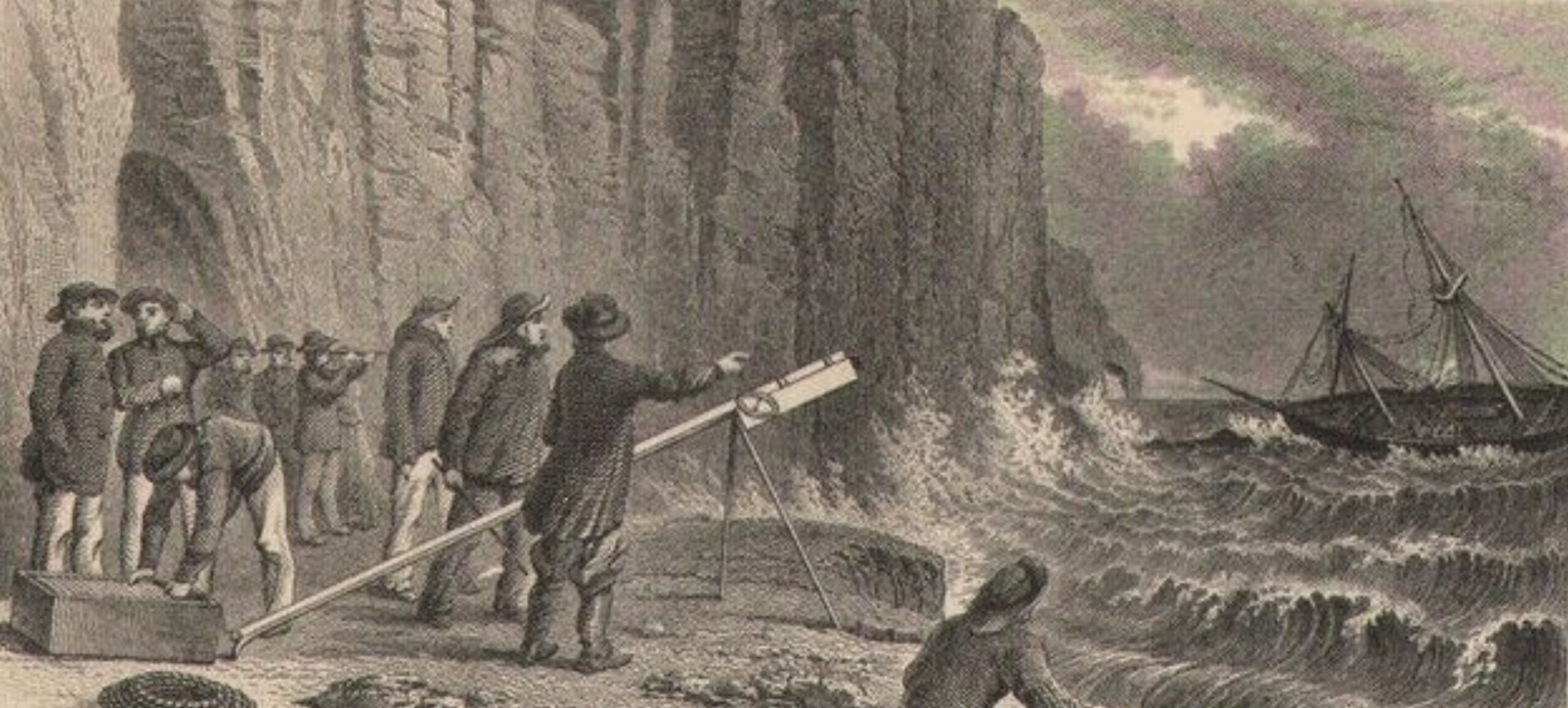

Rescuers tried to use a rocket to carry a rope to Descobrador but it fell short of the wreck. Another rescuer (the master’s assistant from HMS Flying Fish) attempted to swim to the ship with a spar attached to a rope but upon reaching the vessel he was overwhelmed by the tremendous surf and washed ashore—alive but exhausted. An attempt was also made to launch a whale boat but the moment it touched the water it was dashed to pieces.

The rescue was finally carried out by American sailor Joseph Roach who swam to the vessel with a rope, pulled a length of it onto Descobrador, tied one end around Mrs. Seale and leapt overboard so rescuers could haul them to shore. Mrs. Seale arrived completely insensible but was soon revived. Upon seeing his wife safely ashore Mr. Seale tied the rope around his waist and was hauled to shore. Amazingly, all of this occurred in just ten minutes. While the rescue from Descobrador was underway another slaver parted her anchor cables and headed for shore “as if propelled by steam.” She landed against the hull of Descobrador and within just moments of the Seale’s departure both vessels broke apart.

Around noon the Brazilian schooner Acquilla and the brigantine St. Domingo lifted their anchors and drove ashore.

An hour later a wave so huge that it blocked out “all behind it, almost even the very light of the sun” began rolling towards island. The enormous wave lifted the 230-ton storeship Rocket into a vertical position with her bow up and her stern down and flipped her completely upside down. When the wave passed, Rocket and all of the small boats lying around her were simply gone.

That same wave caused destruction all along the shoreline: it tore apart the large iron tanks that provided water to the ships; it ripped a large iron crane off the lower wharf and carried it more than fifty yards into the coal yard which was also destroyed; it swept away a verandah built at the back of the wharf to shelter captains and others waiting transport to their vessels (luckily the spectators had abandoned it for a safer location just a few minutes earlier); and much of the lower wharf and landing place were destroyed.

The next ships to go were the schooner Eufrazia and the brigantine Esperanza which were both buried by huge wave. Eufrazia disappeared instantaneously while the Esperanza was dismasted and eventually drifted out to sea a complete wreck. The final losses occurred around 5:00 when the brigantine Julia and the brig Quatro de Marco were lifted from their anchors and dashed against the West Rocks. Upon hitting the rocks Julia was instantly smashed to pieces while the Quatro de Marco was lifted by an enormous wave and thrown on top of a large old anchor that had been embedded in the West Rocks in 1734 as a shore fast for ships. As the Quatro de Marco broke up the sea carried the large anchor away.

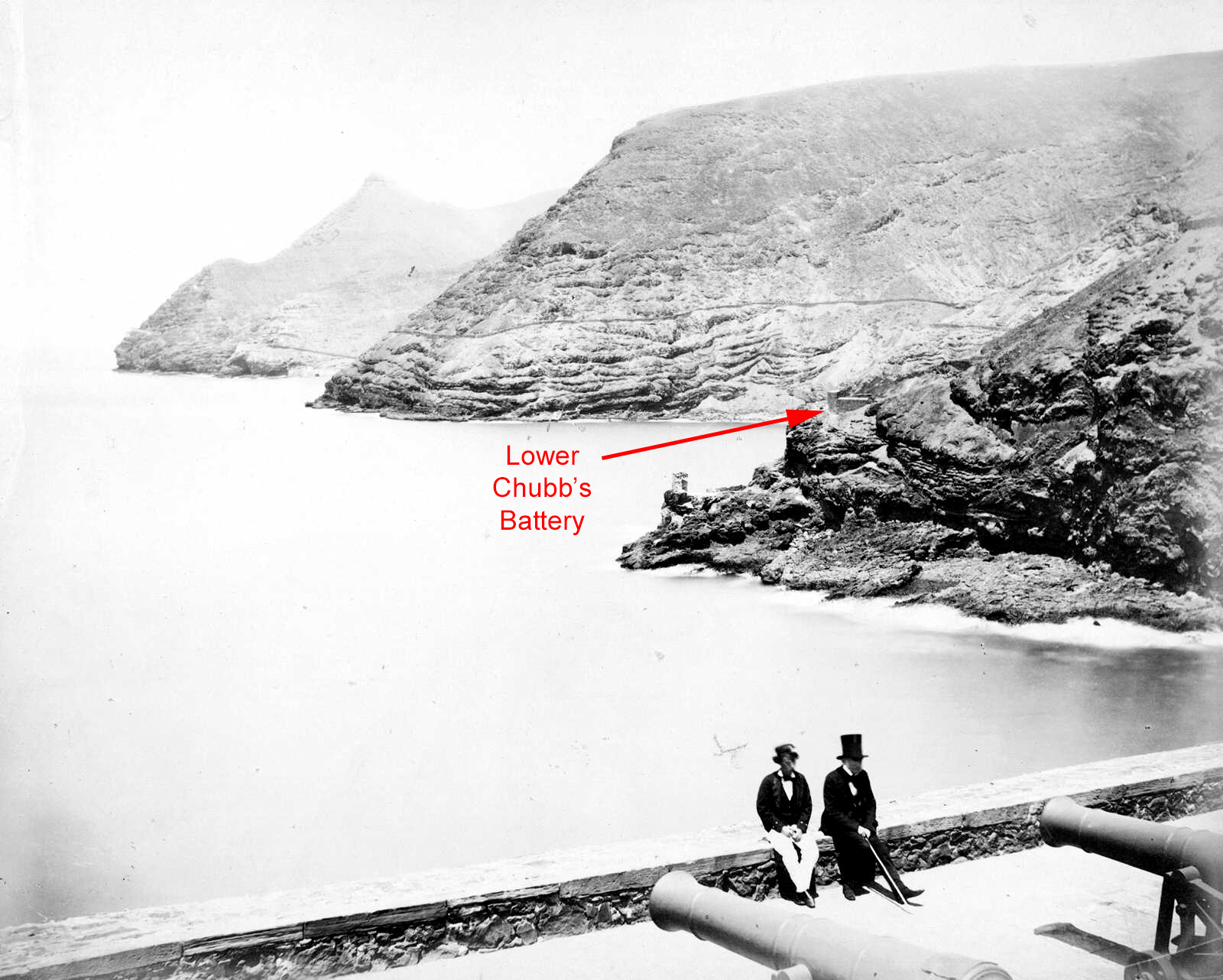

By sunset, eleven slave trading vessels, two merchant vessels, fourteen passage boats and four fishing boats had been driven onto the glacis and curtain wall of the James Line or the rocks around the town and “dashed to atoms.” Along with the infrastructure damage I already mentioned many of the islands defensive fortifications were also damaged. At Rupert’s Valley the sea rolled inland a distance of 216 feet and destroyed everything in its path. The tremendous waves split the wall of Lower Chubb’s Battery (it was six feet thick!) and swept the parapets to either side of it and a 24-pound carronade (about 1500 lbs) into the sea. The fortifications at Lemon Valley (to the west of Jamestown) were also damaged. By the time the waves subsided the outer curtain wall of the entire James Line had been destroyed and the glacis in front of it was completely impassable. Astoundingly, there were only three fatalities.

So exactly what causes St. Helena’s infamous rollers?

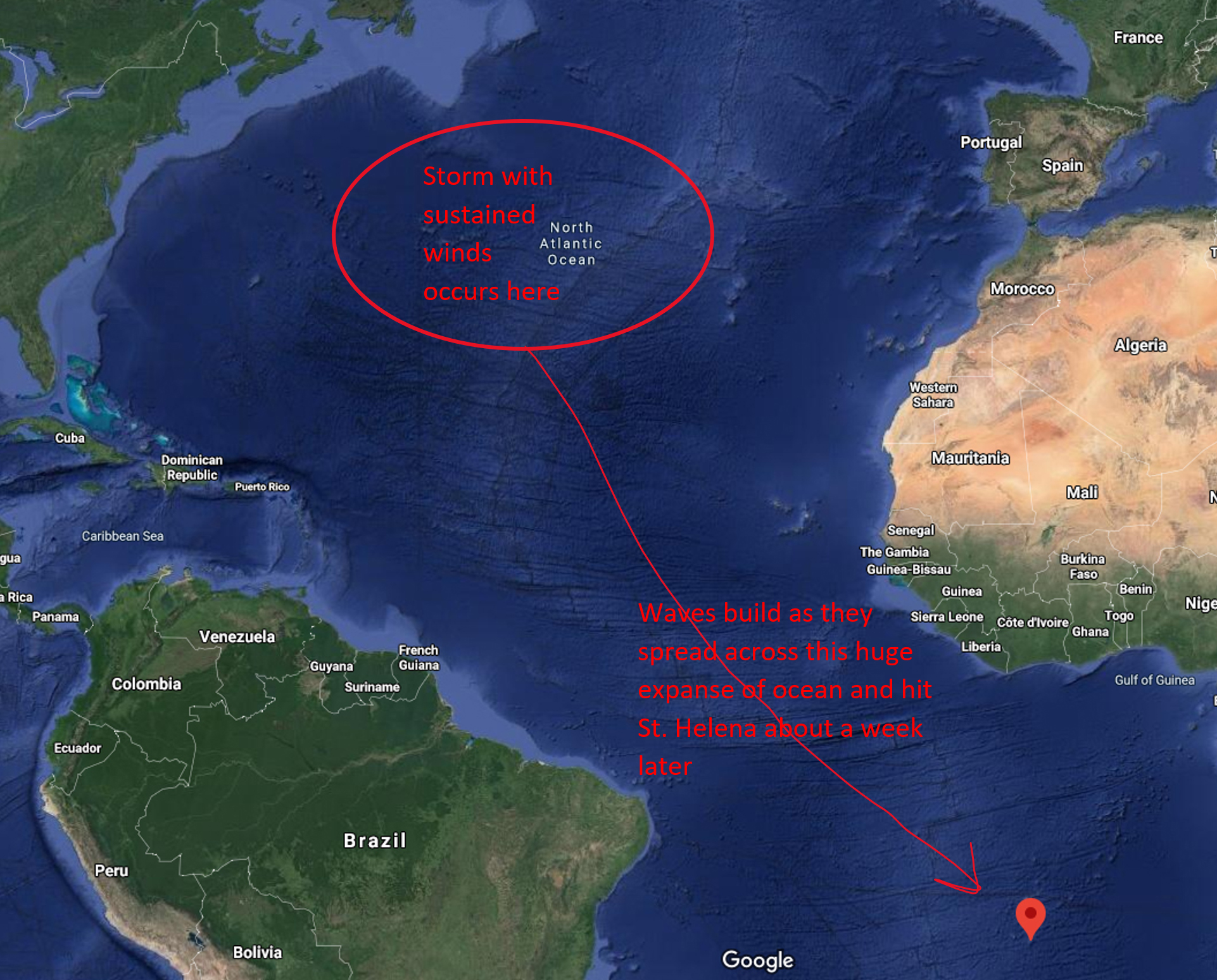

There have been many theories regarding their origin over the centuries. The rollers are seasonal, primarily occurring in October and February, so that rules out things like earthquakes and tsunamis. Cleveland Abbe, stationed aboard USS Pensacola at Ascension Island during the 1890 United States Scientific Expedition suggested the rollers were caused by strong trade winds and the deflection of the waves they produced by shoals. As I looked into the many theories I discovered an article by researchers J. M. Vassie, P. L. Woodworth, and M. W. Holt in the Journal of Atmospheric and Ocean Technology that pretty firmly established the cause of the roller events. They had studied data collected by tide gauges at Ascension and St. Helena Islands after a roller event on October 26, 1999 and determined it was caused by an unusually large deep-ocean swell generated by the remains of Hurricane Irene in the North Atlantic one week earlier. Irene had remained stationary for two days in the central North Atlantic which had enabled the sustained, strong, unidirectional winds to generate the deep-ocean swell that hit the islands a week later.

If the roller events are caused by storms in the North Atlantic I began to wonder about what the weather was doing in February of 1846. It must have been pretty severe considering the height of the waves that hit St. Helena (the worst that have ever occurred). Newspapers from the time indicate the weather along the east coast was particularly ugly and a number of ships reported experiencing severe gales at sea.

For me, one story in particular stood out from the rest. On February 4th the ship Brooklyn left New York for Yerba Buena on the West Coast [the city that would be renamed San Francisco less than a year later]. Although New York newspapers reported the ship was carrying “immigrants,” it was actually carrying around 235 Mormons trying to flee persecution in the United States (many others were traveling west overland with Brigham Young). Ironically, by the time Brooklyn arrived on the West Coast the territory had been acquired from Mexico so the people who thought they were “escaping” the United States ended up right back in it!

About four days after clearing port the ship ran into a terrible gale that lasted for four days (February 8th to 12th). Passengers described “mountain high” waves breaking over the decks and stated they were “tossed about like feathers in a sack” below decks. The seas were so rough women and children were lashed to their berths at night so they wouldn’t be tossed out of bed. Even the ship’s captain, Abel Richardson, described the storm as “the worst gale I have ever known since I was a master of a ship.” Just a few days later, on February 15th, what may have been the same storm hit the east coast driving twelve or more vessels ashore in New Jersey and New York including the packet ship John Minturn. There were hundreds of fatalities among the lost vessels.

Although this isn’t definitive proof that this particular storm caused the roller event on February 17 its location, long duration, severity and the timing certainly seem suspect!

Interested to learn more? Check out these articles and publications online.

Modern research on the cause of rollers in St. Helena:

“An Example of North Atlantic Deep-Ocean Swell Impacting Ascension and St. Helena Islands in the Central South Atlantic”, published in the Journal of Atmospheric and Ocean Technology, Volume 21, Issue 7, July 2004, pages 1095-1103 (https://journals.ametsoc.org/jtech/article/21/7/1095/2606/An-Example-of-North-Atlantic-Deep-Ocean-Swell)

Regarding the immigration of Mormans:

Voyage of the Brooklyn by Lorin K. Hansen (https://www.dialoguejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/sbi/articles/Dialogue_V21N03_49.pdf)

On the island of St. Helena:

St. Helena: The historic island from its discovery to the present date, by E.L. Jackson, illustrated from photographs. 1905 (https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001872661)

Forts and Batteries, Defensive Military Installations (http://sainthelenaisland.info/forts.htm)