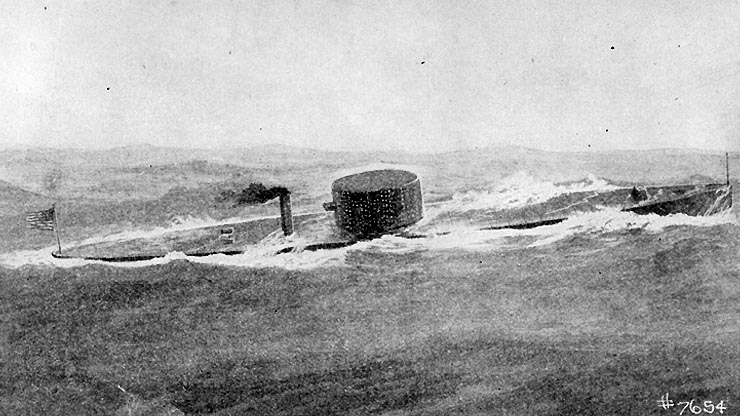

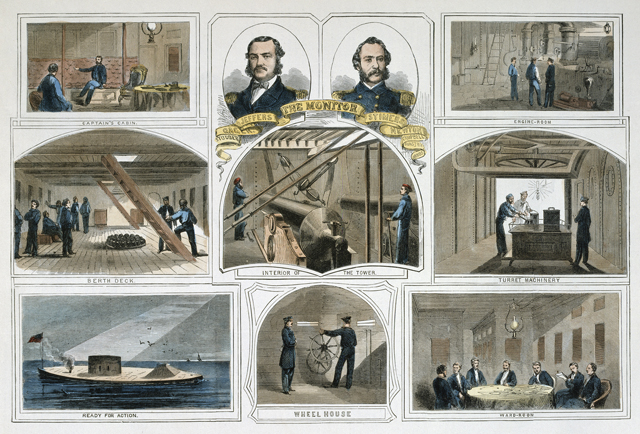

After the ironclad’s showdown with CSS Virginia on March 9, 1862, USS Monitor was considered the ‘little ship that saved the nation.’ The Monitor continued to serve in Virginia waters until September 30 when the ironclad was sent to Washington Navy Yard for much needed repairs. The ship’s complement changed due to desertion and re-assignment; nevertheless, it left the yard on November 8 to return to Hampton Roads. Having received a variety of improvements, Monitor was positioned off of Newport News Point, guarding against any excursion by the Confederate ironclad CSS Richmond.

CAN WE ATTAIN FRESH LAURELS?

While awaiting orders, Monitor’s crew enjoyed oysters and other good food in Hampton Roads. Ordinary Seaman Jacob Nicklis wrote home, “I am getting fat and look tough & hardy.” [1] The entire crew longed for action as they all wished to gain greater laurels for their ship. Acting Assistant Paymaster William Keeler knew that the Confederate ironclad, CSS Richmond, would never come down the James River. He, as others, continued to speculate where the Monitor might be sent to operate against a major Southern port. In actuality, the US Navy was considering two options: one against the blockade runners’ haven, Wilmington, North Carolina, or to recapture Fort Sumter in the hated home of secession, Charleston Harbor, South Carolina.

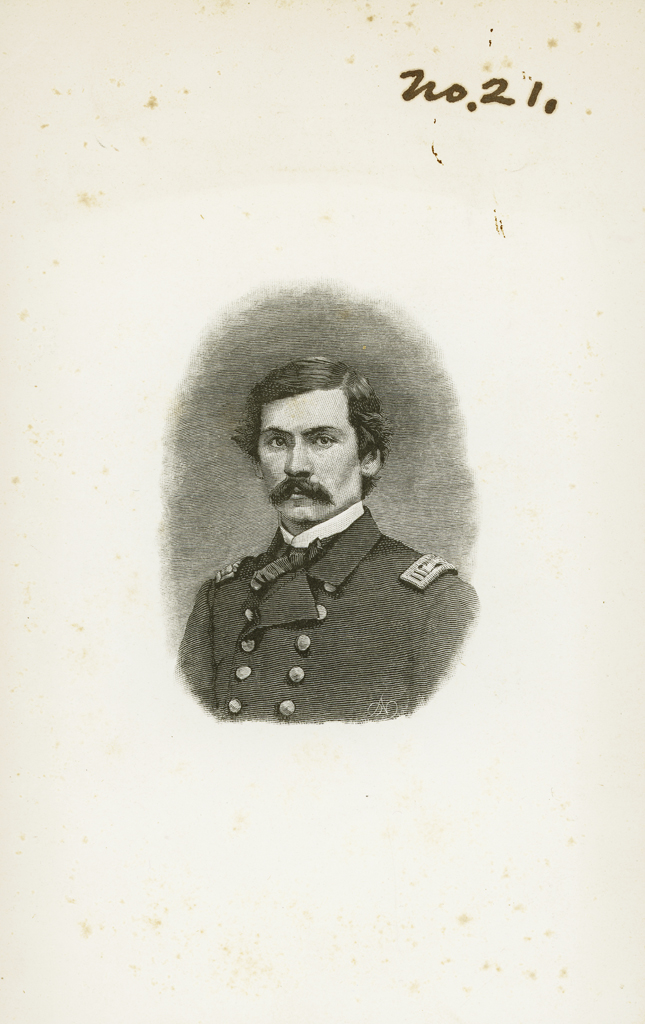

On December 23, 1862, all hands were mustered, and an order from the War Department was read by Monitor’s captain, Commander John Pyne Bankhead, forbidding any army or navy personnel from communicating any news about military operations. The dictum sent a clear message to the crew that they would soon be headed south. Many thought it would be Charleston.

CHRISTMAS DAY

Christmas Day was celebrated in Hampton Roads in a most merry fashion. Visiting French and British warships traded salutes with Fort Monroe. The HMS Ariadne and USS Colorado commenced target practice with their heavy guns . Soon, according to William Keeler, the “powder smoke hung like a thick fog over the water & was so dense that at one time it was impossible to see a few yards distant.”[2] There were celebrations everywhere along the shoreline.

The shipboard meals were fabulous. The officers supplemented their Christmas dinner with specialties sent from home, including raisins, oranges, pies, cakes, and nuts, which enhanced the variety of fish, fowl, and meats that were served. But First Class Fireman George Geer and others did not enjoy the day. Geer noted that he had paid one dollar for the cook to create a splendid meal; unfortunately, he thought it was poorly cooked.

Jacob Nicklis thought otherwise and described the meal: “We had chicken stew & then stuffed Turkey mashed potatoes & soft bread after this we had a plum pudding & some nice fruitcake with apples for desert[sic].” [3]. Despite these differing opinions about their Christmas meal, the enlisted men still had to work most of the day preparing the ironclad for an ocean voyage. Bankhead had received orders on that festive day to take Monitor out to sea.

PLANNED PURPOSE AND DESTINATION

The Monitor’s Christmas Day orders detailed the ironclad to Beaufort, North Carolina. There it was to join two of the new Passaic-class monitors, the Passaic and Montauk, for a joint Army-Navy expedition against Wilmington, North Carolina. Eventually two other monitors, the Weehawken and Patapsco, would join this squadron in January 1863.

# NH 42803

Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles had sought to strike at Wilmington since the summer of 1862. Located near the mouth of the Cape Fear River, the port city was excellent for blockade running. Just 670 miles from Bermuda, the Cape Fear had two entrances — New Inlet and Old Inlet — into the river from the Atlantic Ocean. This situation made it difficult for the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron to stem the flow of materials in and out of Wilmington.

Welles’s concept was to move the monitors into the Cape Fear River via the Old Inlet and to bombard Fort Fisher, guarding the New Inlet, and Fort Caswell, guarding the Old Inlet, into submission. While the monitors were to subdue the Cape Fear forts, Major General John Foster’s army at New Bern, North Carolina, would move south and besiege Wilmington. Once the monitors had passed the forts, the port city would be shelled until surrendered. The plan had many merits; but unfortunately, the monitors had to steam from Hampton Roads down the coast to Beaufort to implement it.

THIS IS NOT ‘A SEAGOING VESSEL’

News of the impending voyage south was not well received by the officers or enlisted men, particularly crew members who had experienced the ironclad’s harrowing trip from New York to Hampton Roads in March.

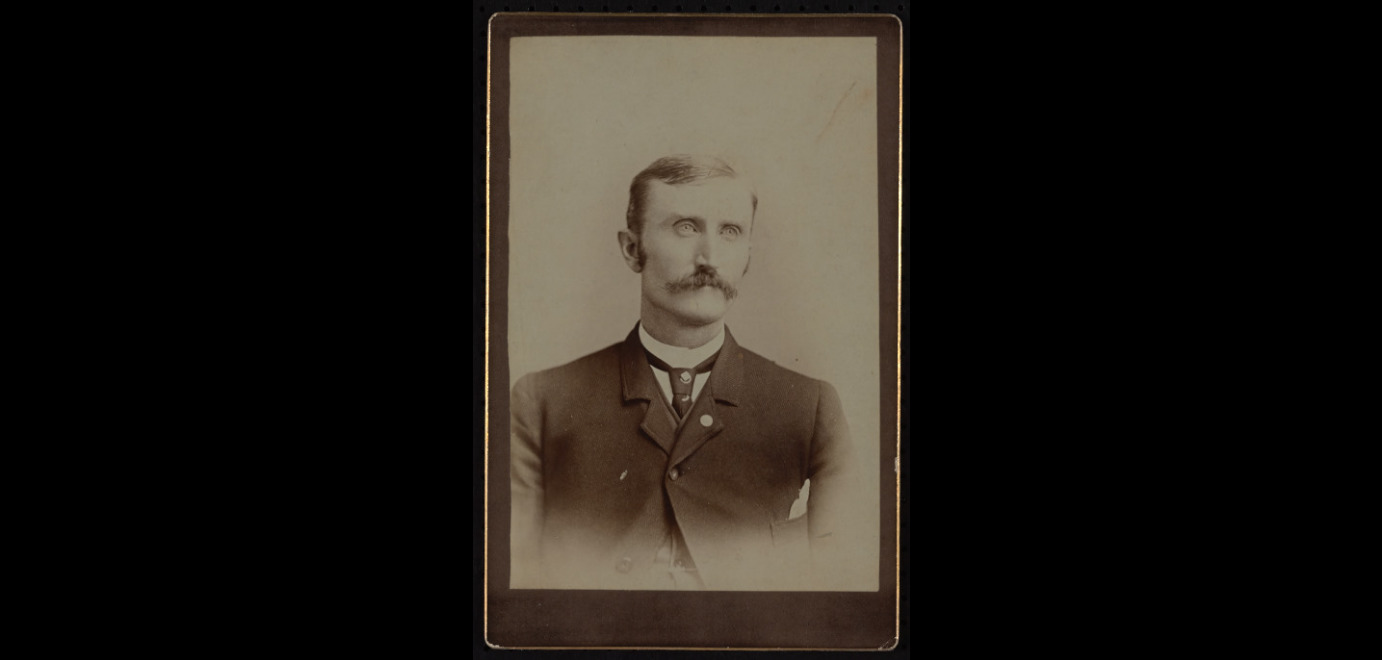

Lieutenant Samuel Dana Greene warned, “I do not consider this steamer a seagoing vessel. She has not the steam power to go against a headwind or sea, and…would not steer even in smooth weather, and going slow she does not mind her helm readily. [4] Rumors of Monitor’s last sea voyage were heard by many of the new crew members, prompting Jacob Nicklis to write his father, “They say we have a pretty rough time around Hatteras, but I hope that it will not be the case.” [5]

PREPARATIONS

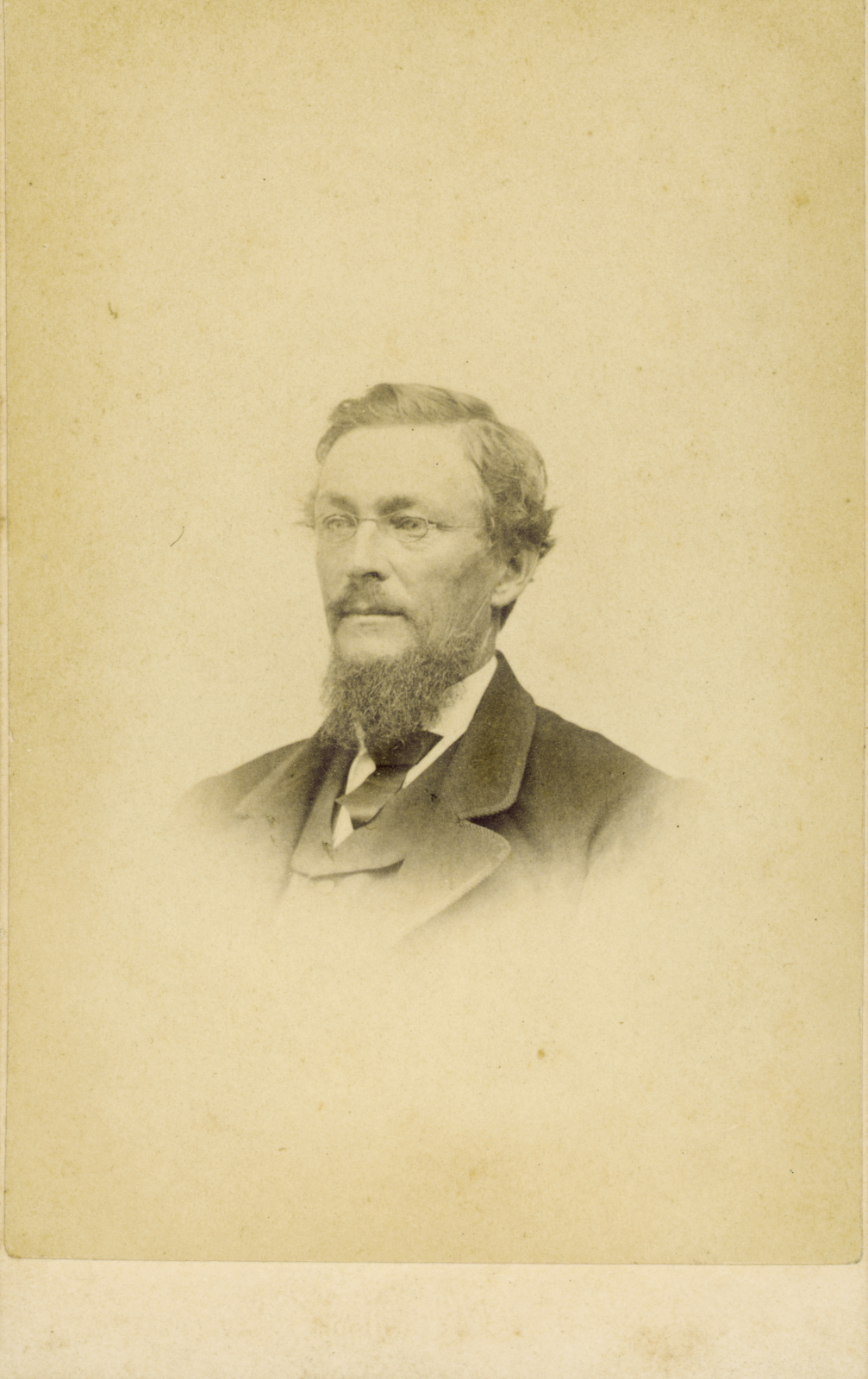

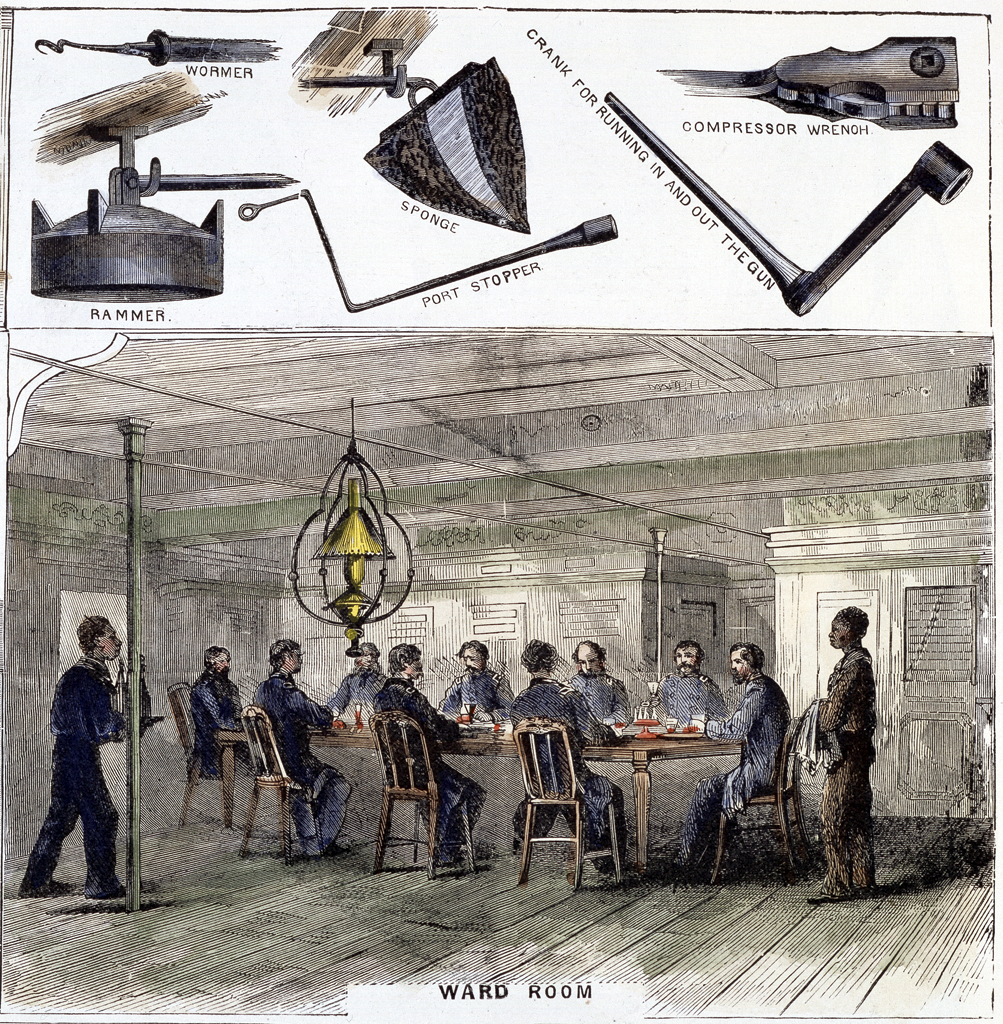

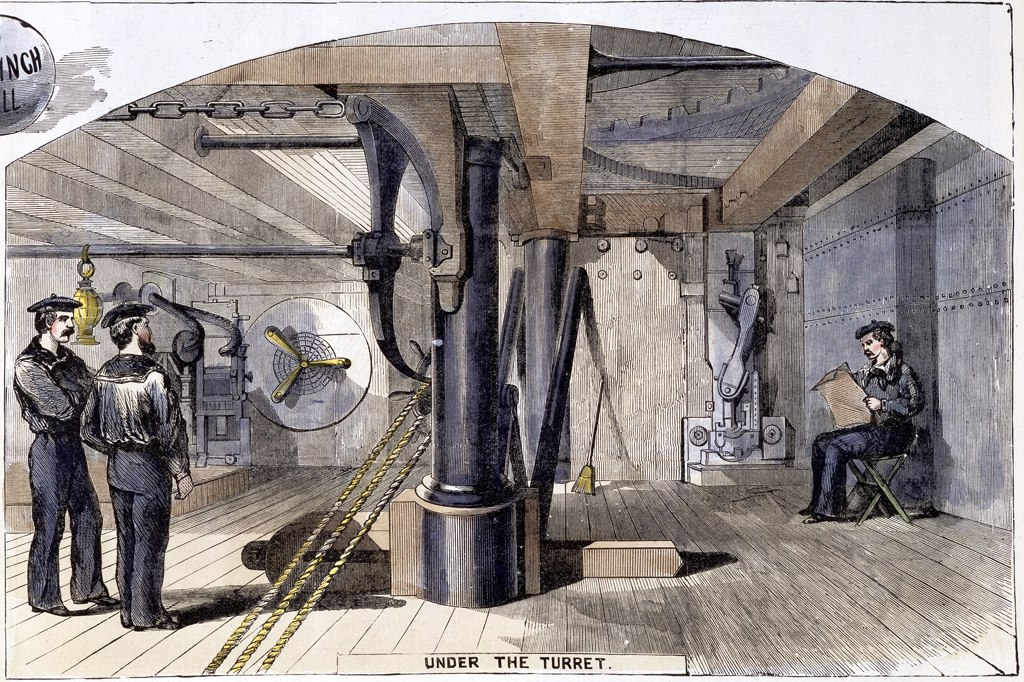

Despite the fears associated with the trip, Bankhead prepared his ship for sea. The ship’s new surgeon, Dr. Grenville Weeks, noted that the “turret and sight holes were caulked and every possible entrance for water made secure, only the smallest hole being left in the turret top.”[6]

George Geer worked on securing the hatches “with Red lead putty, and the Port Holes I made one inch thick and in fact had everything about the ship in a way of opening tight.” [7] Bankhead thoroughly followed the Navy Department’s instructions to guard the vessel against leaks. Unfortunately, once again, like when Monitor went south from New York to Hampton Roads and nearly sank, the Navy ignored the fact that John Ericsson had designed the turret to fit snugly onto a brass ring set into the deck. This design feature was rejected as not being watertight, and instead, Monitor’s turret was jacked out of its ring and oakum was packed around its base. Geer recalled that the men working on this task “did not put any Pitch over it and the sea soon washed the oakum out.”[7]

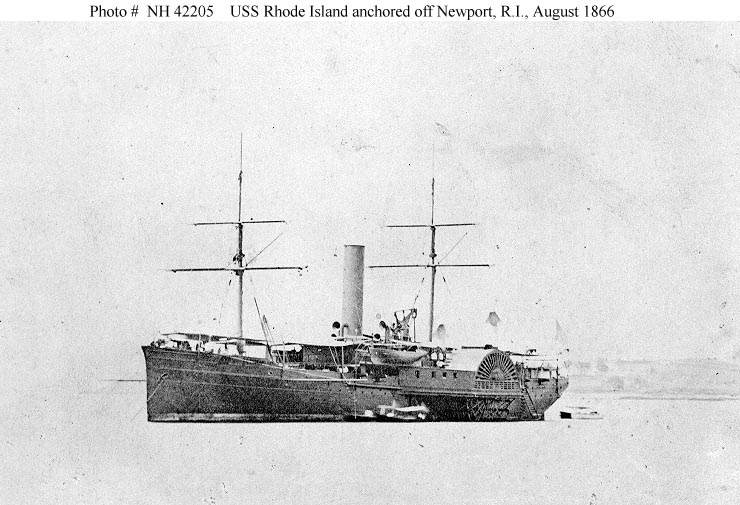

The powerful 236-foot-long sidewheeler USS Rhode Island, captained by Commander Stephen Decatur Trenchard, had recently arrived in Hampton Roads following a refit in Boston’s Charlestown Navy Yard. It was detailed to tow USS Monitor to Beaufort. Trenchard’s ship had run aground entering the Chesapeake Bay on December 19, but was declared undamaged. Both the Rhode Island and Monitor were to be accompanied on their voyage south by USS State of Georgia towing the Passaic.

THE VOYAGE BEGINS WITH GOOD WEATHER

The expedition was delayed by a heavy storm that struck Hampton Roads on December 27 and 28. William Keeler thought the storm was a good omen and commented that Monitor “shall hold on here till the storm is over & take advantage of the calm that follows for our trip down the coast.”[8] The day of December 29 began clear and pleasant with every prospect of good weather continuing for the trip to Beaufort. Accordingly, Trenchard began to prepare Rhode Island for the voyage. At 2:30 p.m., the sidewheeler took up two towlines attaching Rhode Island to Monitor and steamed past the Virginia Capes south to North Carolina.

The first evening at sea was pleasant. Keeler noted that “a smooth sea & clear skies seemed to promise a successful termination of our trip & an opportunity of once more trying our metal against the rebel works & making the ‘Little MONITOR’ once again a household name.”[9]

THE WEATHER TURNS BAD

The next morning, clouds were seen off to the south and west. Commander Bankhead later reported: “We began to experience a swell from the southward with a slight increase of wind from the southwest, the sea breaking over the pilothouse forward and striking the base of the tower, but not with sufficient force to break over it. Found that the packing of oakum under and around the base of the tower had loosened somewhat from the working of the tower as the vessel pitched and rolled. Speed at this time was about five knots, ascertaining from the engineer of the watch that the bilge pumps kept her perfectly free, occasionally sucking. Felt no apprehension at this time.[10]

George Geer remembered the waves washing the oakum out beneath the turret, where the water “came down on the Berth Deck in Torents [sic]. But, our pumps were sufficient.” [11] Shortly thereafter, Monitor made a signal to Rhode Island to stop. Bankhead wanted to make adjustments to the tow line; this was safely accomplished, and the two ships proceeded on course.

NOTHING TO FEAR

The winds increased as Monitor steamed southward. By midday, the sea began to break over the ironclad and wash up against the turret in a fearful rush. By 1:00 p.m., Rhode Island and Monitor passed Cape Hatteras Lighthouse and began to work their way around the Cape itself. The winds continued to increase as the two vessels made little headway against the storm. Many thought that as soon as Monitor passed the Cape, the storm would pass. Instead, the storm increased. Winds reached gale force, and the sea had grown very rough. Bilge pumps were started to remove the small amounts of water coming into the ironclad.

Despite the storm, the officers sat down to dinner, as Keeler remembered, ”everyone cheerful and happy & though the sea was rolling and foaming over our heads the laugh & jest passed freely ‘round; all rejoicing that at last our monotonous, inactive life had ended & the ‘gallant little MONITOR’ would soon add fresh laurels to her name.” [12]

Meanwhile, Bankhead, using chalk messages written on a blackboard, informed Rhode Island that if Monitor needed help during the evening, a red lantern would be displayed next to the ironclad’s white running light. Bankhead recorded: “Toward evening the swell somewhat decreased, the bilge pumps being found simply sufficient to keep her clear of water that penetrated through the sight holes of the pilothouse, hawse hole, and the base of the tower (all of which had been well caulked previous to leaving.)” [13]

THE STORM RISES IN FURY

As darkness came, Rhode Island and Monitor were separated from Passaic and State of Georgia, and the storm increased in its ferocity. Waves dashed across the deck and broke with tremendous force. Bankhead recalled that he “found the vessel towed badly, yawning very much, and with the increased motion making somewhat more water around the base of the tower. He ordered engineers to put on the Worthington pump and bilge injection and get the centrifugal pump ready and report to me immediately if he perceived any increase of water.” [14]

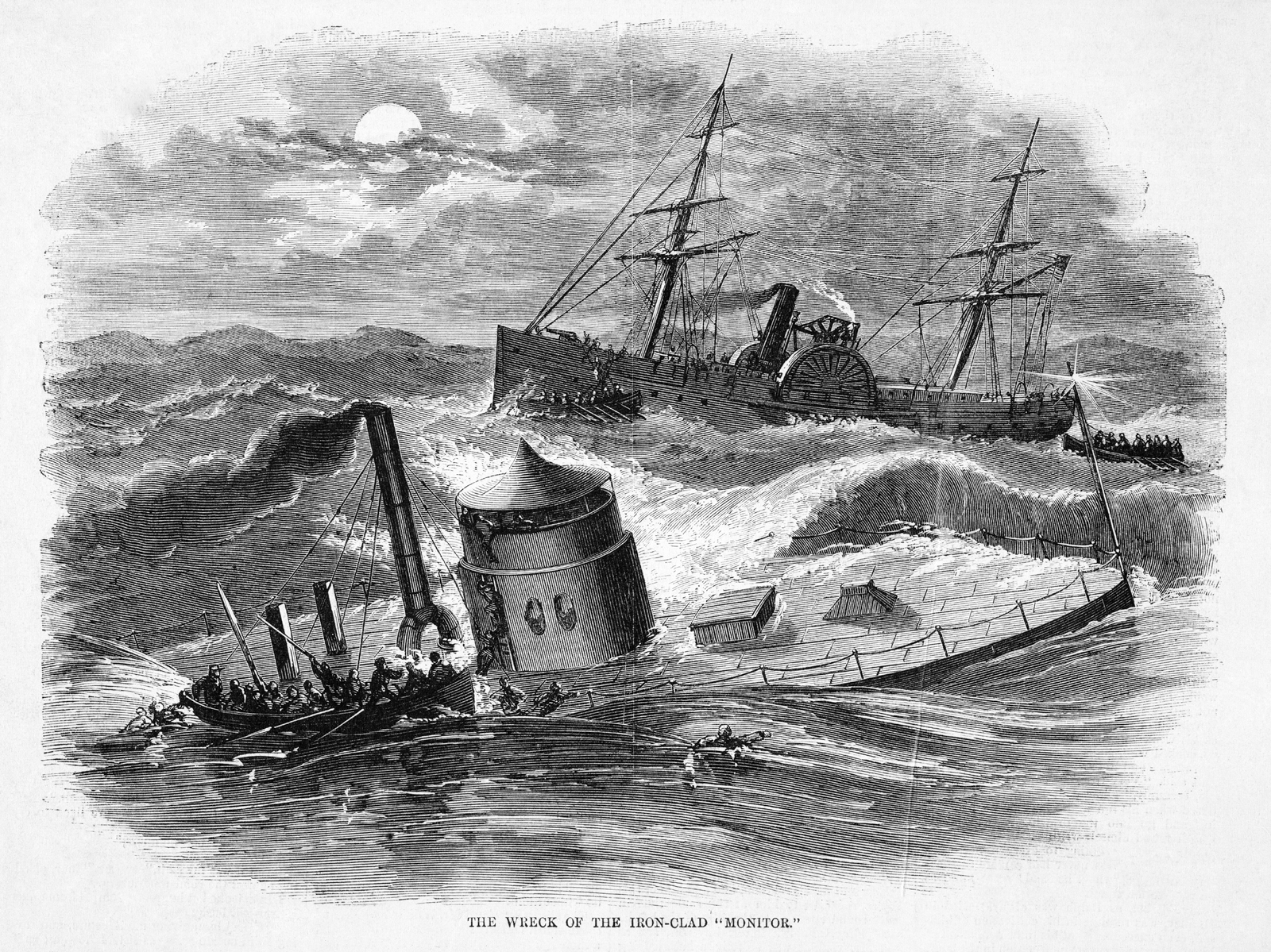

While the Worthington steam pumps temporarily stemmed the flow of water, Monitor was suddenly struck by a series of fierce squalls. The ironclad was now in “very heavy weather, riding one huge wave, plunging through the next, as if shooting straight to the bottom of the ocean.”

Landsman Francis Butts continued his description of the effects of the heavy gale on the ironclad, stating that the ship would drop into a wave “with such force that her hull would tremble, and with a shock that would sometimes take us off our feet. [15]

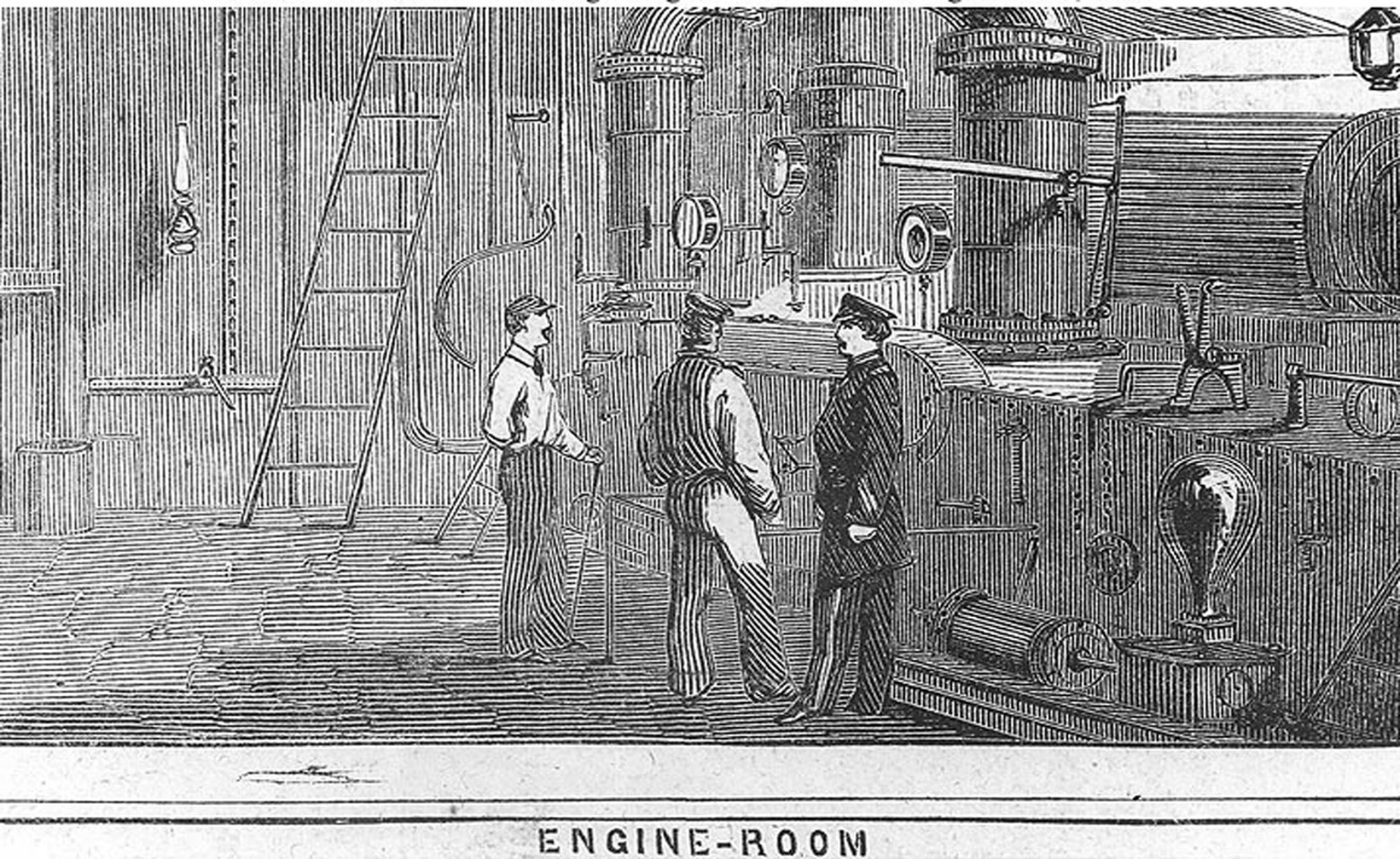

When the Worthington pumps failed to stem the rising water, the call came from the engine room, “the water is gaining on us, sir.” This report “sounded ominously”[16] to William Keeler; however, Bankhead ordered the large Andrews centrifugal steam pump into action. This pump was capable of removing 3,000 gallons a minute. Unfortunately, this pump also proved inadequate to stop the flow of water, which had by 9:00 p.m., had risen over a foot deep in the engine room.

As the storm increased in its fury, Bankhead put the crew to work on the hand pumps and organized a bucket brigade. The bailing served little purpose other than to lessen the panic among the crew. “But our brave little craft struggled long and well,” wrote William Keeler. “Now her bow would rise on a huge billow and before she could sink into the intervening hollow, the succeeding wave would strike her under her heavy armor with a report like thunder and violence that threatened to tear apart her thin sheet iron bottom and the heavy armor which it supported.”[17]

IN A SINKING CONDITION

Unfortunately, the water was rising rapidly. When it reached above the engine room floor, Keeler noted that it “was the death knell of MONITOR.[18] Bankhead later wrote: “The sea about this time commenced to rise very rapidly causing the vessel to plunge heavily completely submerging the pilothouse and washing over and into the turret and at times into the blower pipes. Observed that when she rose to the swell, the flat under surface of the projecting armor would come down with great force, causing considerable shock to the vessel and turret, thereby loosening still more packing around its base.”[19]

Leaks appeared everywhere. The Monitor was going “head on” into the storm, and the constant pounding of the waves forced the upper deck to begin separating from the lower hull.

Acting Master Louis Napoleon Stodder believed that the situation was exacerbated by “the RHODE ISLAND, being a powerful steam ship, towed us faster than our engines could keep up with, and the sea beating under our 15-foot overhang at the bow ripped us apart.” [20] Every time the ironclad crashed down into the sea, more water was forced into every hole, gap, crevice, and crack.

DESPERATION

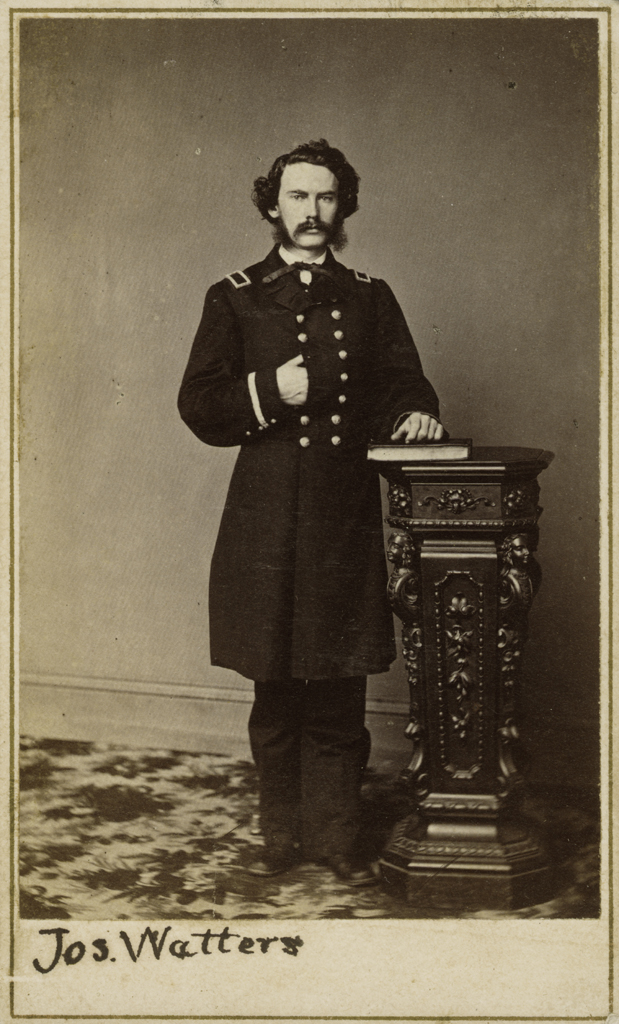

The situation had become desperate aboard the ironclad. Nothing seemed to arrest the influx of water. By 10:00 p.m., furnace fires were extinguished by the ever-rising seawater, rendering Monitor helpless. Second Assistant Engineer John Watters reported that when the boilers lost steam, “the main engines stopped, the Worthington and centrifugal pumps still working slowly, but finally stopped.” The foundering ironclad appeared isolated in a sea of hissing, seething foam. Bankhead ordered the red lantern displayed and thus tried to signal Rhode Island for assistance. Signal flares were launched, yet the big sidewheeler did not notice Monitor’s dilemma. “Send your boats immediately, we are sinking,”[21] Bankhead shouted at the paddler.

AWAITING RELIEF

“Words cannot depict the agony of those moments as our little company gathered at the top of the turret, stood with a mass of sinking iron beneath them, gazing through the dim light, over the raging waters and an anxiety amounting almost to agony for some evidence from the only source to which we could look for relief,” [22] Keeler painfully remembered. Even though Monitor had been fitted with two new ship’s boats while being overhauled at the Washington Navy Yard, those “lifeboats” had been stored aboard Rhode Island for the voyage south. The crew was helpless to save themselves without assistance from Rhode Island. When all seemed lost, “the clouds now began to separate, a moon of about half-size beamed out upon the sea,” Frank Butts remembered, “and the RHODE ISLAND, now a half mile away, became visible. Signals were exchanged, and I felt that the MONITOR would be saved.”[23]

When Bankhead realized that Rhode Island was finally responding to his pleas for assistance, he immediately recognized that the towline to the Rhode Island could be the end for both vessels. He feared that when the ships hove together, Monitor could surge forward and pierce the sidewheeler’s hull with its iron bow. Accordingly, Bankhead ordered several men forward to cut the cables connecting the two vessels.

Quarter Gunner James Fenwick attempted it but was swept overboard. Then Boatswain’s Mate John Stocking took an ax and frantically chopped at the cable until he, too, was washed into the sea. Finally, Acting Master Louis Stodder rushed forward to cut the 13 inch-thick line. “It was not an easy job,” Stodder recalled, “and while I was hacking at it a big sea came over the bow.”.[24] Somehow, Stodder held on and finished the job. Once the line was parted, Bankhead ordered the anchor dropped in order to stop the ironclad’s pitching. While this action was somewhat successful, dropping the anchor also loosened the watertight packing around the anchor well, allowing still more sea water to flow into the wallowing ironclad.

As the Rhode Island backed towards Monitor, one of the towlines tangled the port paddlewheel. This caused the sidewheeler to temporarily lose control and it almost collided with the sinking ironclad. The Rhode Island’s crew worked furiously to stabilize the steamer and then launched lifeboats to retrieve Monitor’s crew.

The ironclad’s crewmen anxiously waited for the boats from Rhode Island to arrive. Keeler was placed in charge of a bailing party to try to staunch the flow of water. Frank Butts was in the turret to pass bails up and down to the hatch of the turret. Butts claimed that he became so annoyed by the wailing of a cat that he placed the feline into a barrel of one of the XI-inch Dahlgrens and stuffed a wad in after it. Unfortunately, this did not stop the cat’s mournful howling.

Finally, the Rhode Island’s rescue boats were seen nearing the ironclad with the sidewheeler following close behind them. The rough seas forced the steamer towards the Monitor and nearly crushed the lifeboats between the two ships. The Rhode Island managed to pull away and stood off the Monitor, a quarter mile away.

ABANDON SHIP

In the meantime, Bankhead readied the crew to abandon Monitor. The ironclad’s captain and several other officers went through the ship to make sure all were ready to enter the lifeboats. According to Frank Butts, Third Assistant Engineer Samuel Augee Lewis was so seasick that he was unable to get out of his bunk. Lewis had been aboard the ironclad only 60 days, and this was his first sea voyage; it is no wonder he had become so ill.

William Keeler went to his stateroom to recover his books and papers and found “the water nearly to my waist & swashing from side to side with a roll of the ship.” Keeler groped his way through the “thick darkness rendering more dense if possible by the steam, heat & gas which was finding its way from the half-extinguished fires of the engine room”.[25] The paymaster quickly realized that he could not retrieve his files without endangering his own life. Therefore, Keeler started to make his perilous way back to the turret top.

“Everything was enveloped in a thick murky darkness, the waves dashing violently across the deck over my head; through the wardroom where the chairs & tables were surging violently from side to side, threatening severe bruises if not broken limbs; then up a ladder to the berth deck; across that & up another ladder into the turret around the guns & over the gun tackle, shot, sponges & rammers we’ve been broken loose from their fastenings & up the last ladder to the top of the turret.”[26]

George Geer had finally abandoned his pump when it stopped working and waded through the knee-deep water towards the turret. He realized that everyone was ready to leave the ship as there was no one left to pass a bail on to.

THE RESCUE BEGINS

It seemed like an eternity to the Monitor’s crew as they waited for Rhode Island’s boats to come alongside the Ironclad. “It was a scene well calculated to appall the boldest heart,” Keeler wrote, adding, “Mountains of water were rushing across our decks & foaming against our sides; the small boats were pitching & tossing about on them or crashed against our sides mere playthings on the billows; the howling of a tempest the row & dash of waters; the hoarse orders through the speaking-trumpet of the officers; the response of the men the shouts of encouragement & the words of caution the bubbling cry some strong swimmer in his agony & the whole scene lit up by the ghastly glare of the blue lights burning on our consort, formed a panorama of horror which time will never efface from my memory.”[27]

Many crew members weakened as they waited. George Fredrickson returned a watch he borrowed from Peter Williams, stating, “Here this is yours; I may be lost.” [28] A statement made in simple fear proved to be uncannily prophetic.

Bankhead finally ordered Keeler to lead the first party to the boats. This meant the men had to descend a ladder down the side of the turret and then move across the wind- and wave-swept deck to the waiting rescue craft. Keeler was hit by a strong wave and tossed into the sea as he crossed the deck. Somehow, the waves threw him back against the sinking ironclad, which enabled him to grab a line from one of the deck stanchions. He held on and successfully made his way safely into a boat.

SAFE AT LAST

Once the two craft were filled, they rowed toward Rhode Island. Keeler later noted: “dangers were not over yet. We were in a leaky, overloaded boat, through whose crushed sides the water was rushing in streams & had nearly a half mile to row over the storm tossed sea before we could reach the RHODE ISLAND.” When the boats finally reached the pitching ship, the men had to climb or be pulled up by ropes onto the steamer’s deck. Keeler, who had hurt his hand, was hauled up by a loop of rope. As Keeler reached the deck, he and the others received the “congratulations & hospitalities of her officers, & I assure you they were not deficient in either.” [29]

When the unloading was accomplished, the boats made ready for a return to the Monitor. One vessel was crushed by the Rhode Island, and only a single remaining craft, commanded by Acting Master’s Mate G. Rodney Browne, made its way back to the ironclad.

Bankhead stood on the deck and held the painter of the craft close to the Monitor as others struggled towards the Rhode Island’s rescue boat. Butts watched from the turret as men before him made their way across the deck and into the boat. Many misjudged the rise and fall of the waves as they jumped towards a lifeboat and fell, lost into the sea. Butts then crossed the deck to help Bankhead, leaving behind him men too terrified to take their chances. These men appeared resigned, hoping they might survive with the ironclad if it were to last out the storm.

Seaman Peter Truscott was the last to leave the turret. His friend ahead of him was washed overboard as he jumped towards the lifeboat and then disappeared beneath the waves, exclaiming, “Oh God!” George Geer dashed across the deck and watched his shipmate Daniel Moore, being forced into the sea and then disappearing. Geer was washed across the deck, but he waited for another wave and this time reached the boat and was saved. Bankhead and Butts were then carried into the ocean by a wave; however, each of them were pulled into the boat by Lt. Samuel Dana Greene. Greene himself had been saved in a similar fashion by Dr. Weeks, who had thrown the executive officer a line, saving his life.

As Browne ordered his loaded craft back to Rhode Island, Bankhead pleaded with those who remained to come with him, but they refused. Browne promised to return for them. “As we pulled away,” Peter Truscott remembered, “I saw the darkness some black forms clinging to the top of the turret.”[30]

When they reached the steamer, the rescue boat was thrown against the towering steamer by a wave. Dr. Grenville Weeks instinctively used his right arm in an attempt to keep the lifeboat from crashing into the larger ship. His arm was caught between the ship and the lifeboat and was dislocated and three of his fingers were crushed by the collision. He never regained use of his arm, a dreadful injury for a practicing surgeon. However, he remained stoic about his destiny. An arm, Weeks would later write, was a small price to pay for a life.”[31]

‘THE MONITOR IS NO MORE’

The rescued men were taken aboard the Rhode Island and given blankets, coffee, food and other necessary comforts. Joseph Watters remembered that he “was about played out,” by the experience and that he “was taken by the Chief Engineer of the RHODE ISLAND who gave me a dry set of clothes, he also gave me his room and treated me very kindly indeed.” [32]

Weeks immediately received medical attention. The steamer’s surgeon quickly amputated three of the doctor’s fingers and reset his arm. Weeks then rejoined his shipmates on the sidewheeler’s deck to watch Monitor’s light shine above the raging sea. “It was half past twelve, the night of 31st of December, 1862,” remembered Frank Butts, “when I stood on the forecastle of the RHODE ISLAND, watching the red and white lights that hung from the pennant staff above the turret, and which now and then were seen as we would perhaps both rise on the sea together until at last, just as the moon had passed below the horizon, they were lost, and the MONITOR…was seen no more.” [33]

‘WHERE STORMS DO NOT COME’

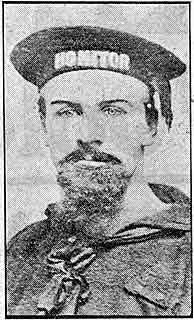

The nation was shocked by the loss of the USS Monitor. Of the 63 men aboard the ironclad when it sank on December 31, sadly 16 were lost. It was miraculous that 47 were saved in such dangerous conditions. Aboard the Rhode Island, the ironclad’s survivors were thankful that they had survived the storm. They acknowledged the sidewheeler’s crew, particularly Commander Stephen Decatur Trenchard and Acting Master’s Mate Rodney Browne, for their fearless determination to rescue everyone they could.

Once back in Hampton Roads, the ‘Monitor Boys’ sent messages home to assure loved ones that they had not gone down with the ironclad. “I am sorry that I have to write you that we had lost the MONITOR,” George Geer reflected to his wife, “but do not worry, I am safe and well.”[34] William Keeler wrote his wife several times about the events off Cape Hatteras, noting in one that the “telegraph has properly informed you before this of the loss of the MONITOR & also of my safety. My escape was a very narrow one…I have been through a night of horrors that would have appalled the stoutest heart.” [35]

Of course it fell on the shoulders of Bankhead and other officers to write the relatives of those who had perished with USS Monitor. Despite his injury, Dr. Grenville Weeks wrote to the sister of Jacob Nicklis stating, “I am too unwell to dictate more than a short sad answer to your note. Your brother went down with other brave souls, and only a good providence prevented my accompanying him. You have my warm sympathies, and the assurance that your brother did his duty well, and has gone to a brighter world, where storms do not come.” [36]

ENDNOTES

1 Letters of Jacob Nicklis, The Mariners’ Museum and Park, Newport News, Virginia.

2 Robert W. Daly Jr., Aboard the USS Monitor, 1862: The Letters of Acting Assistant William Frederick Keeler, US Navy, to His Wife, Anna, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 139-40.

3 Letters of Jacob Nicklis.

4 New York Historical Society, Samuel Dana Greene Papers.

5 Letters of Jacob Nicklis.

6 Grenville M. Weeks, “The Last Cruise of the Monitor,” Atlantic Monthly, 11 (March 1863), 367.

7 William Marvel, ed., The Monitor Chronicles, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000, 235.

8 Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, 251.

9 Ibid.

10 Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (Hereinafter cited as ORN), Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901, Series I, Volume 8: 349.

11 Marvel, The Monitor Chronicles, 235.

12 Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, 254.

13 ORN, 8:350.

14 Ibid.

15 Francis B. Butts, “The Loss of the Monitor,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol.2, edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, New York: The Century Co., 1887, 745.

17 Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, 254.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid., 255.

19 ORN, 8:350.

20 Louis N. Stodder, “Aboard the Monitor,” Civil War Times Illustrated, 1, 1963, 31.

21 ORN, 8:350.

22 Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, 257.325

23 Butts, 746.

24 Stodder, 31.

25 Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, 257.

26 Ibid., 257-58.

27 Ibid., 248.

28 David Robert Ellis, The Monitor of the Civil War, Anneville, PA: 1900, 35.

29 Butts, 747.

30 Samuel Lewis, “Life on the Monitor: A Seaman’s Story of the Fight with the Merrimac; Lively Experiences Inside the Famous ‘Cheesebox on a Raft, ’” in Campfire Sketches and Battlefield Echoes of ‘61-’65, edited by William C. King and William P. Derby, Springfield, MA: 1883, 261.

31 Weeks, “The Last Cruise of the Monitor,” 368.

32 Edward A. Woolen, ed. Woollen/Woolen Family Biographical and Historical Records and Genealogy of Edmund/Edward Woolen of Dorchester County, Maryland, and Richard Woolen of Maryland. Decorah, IA: Anundsen Publishing Company, 1984.

33 Butts, 747.

34 Marvel, The Monitor Chronicles, 231.

35 Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, 252.

36 Letters of Jacob Nicklis.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Butts, Francis B. “The Loss of the Monitor, ” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 2, edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel. New York: Century Co., 1887.

Daly, Robert W., ed. Aboard the USS Monitor, 1862: The Letters of Acting Assistant Paymaster William Frederick Keeler, US Navy, to His Wife, Anna. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1964.

Ellis, David Robert. The Monitor of the Civil War. Anneville, PA: 1900.

Greene, Samuel Dana. Greene Papers, New York Historical Society.

Lewis, Samuel. “Life on the Monitor: A Seaman’s Story of the Fight with the Merrimac: Lively Experiences Inside the Famous ‘Cheesebox on a Raft.’” In Campfire Sketches and Battlefield Echoes of ‘61-’65. William C. King and William P. Derby, eds. Springfield, MA: 1883.

Marvel, William, ed. The Monitor Chronicles. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Nicklis, Jacob. The Papers of Jacob Nicklis. The Mariners’ Museum and Park, Newport News, VA.

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of Rebellion, Series 1, Volume 8, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901.

Stodder, Lewis N. “Aboard the Monitor.” Civil War Times Illustrated, January 1963.

Weeks, Grenville M. “The Last Cruise of the Monitor,” Atlantic Monthly 11 (March 1863).