As we come to the end of Women’s History month, it seems appropriate to write about the magical and mystical powers of women. This may not seem all that surprising – many of us can still remember the eyes that our mothers possessed in the backs of their heads, their incredible ability to know everything, and the special skill that mothers have to always make us feel better when we are sad, sick, or lonely. Even a woman’s ability to multi-task can seem quite magical – and this is only amplified by the current pandemic that has asked women to take on an even heavier burden. But for indigenous circumpolar people of the Arctic, “women’s magic” is actually key to their survival.

For most indigenous groups around the world, there are gender-based roles and skills, and these skills are taught by their elders in order to pass on their traditions from generation to generation. The same is true for the Inuit-Yupik of the arctic. There are numerous indigenous groups in the arctic, and to be completely correct, we would name them all by their specific linguistic group. However, it is generally accepted to call circumpolar indigenous people by the name Inuit-Yupik.

As an interesting side-note, gender is not viewed the same for many indigenous groups around the world as it is in Western nations. Gender is much more fluid: there are men, women, feminine men, masculine women, and individuals who are both. The last three are considered to be highly special individuals who possess two-spirits inside them and can understand two opposing sides. For circumpolar Inuit-Yupik people, in families that had only girls, the eldest daughter would learn the skills of her father, and the same is true of a family with only sons – the eldest son would learn the skills of his mother.

One of the skills that young girls (and occasionally boys) need to learn and perfect is sewing. In fact, without this skill, Inuit-Yupik people could cease to exist in their view. That is because the skill of sewing isn’t just about making clothing, it is also about how they treat the animals that they get their hides from.

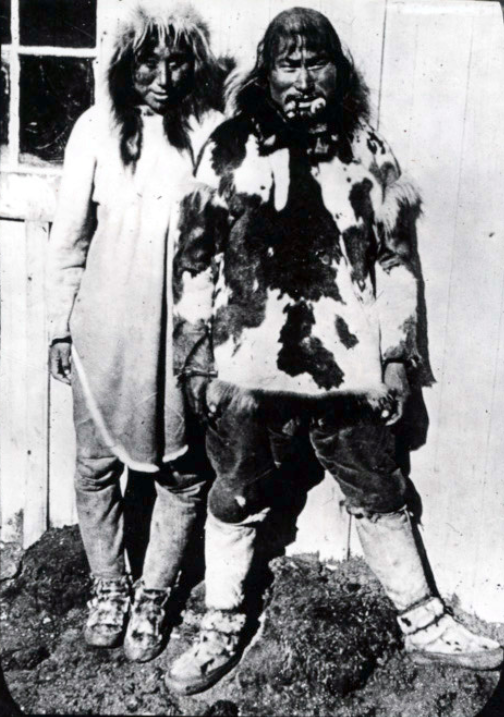

Typically, men of the many Inuit-Yupik groups do the hunting. When they go out onto the water to hunt the seals, walruses, whales, and polar bears that are used for their survival, these men are wearing clothes made from the hides of these animals and are in boats that are covered in these hides. But it isn’t just about a man’s skill in hunting that leads to a successful hunt, it is actually about the woman’s spiritual connection to the animals being hunted and how she channels this through items she has made.

Young girls learn to sew from their mothers and grandmothers. They also learn how to prepare, treat, tan, and stretch animal hides to best serve their intended purpose. In the extreme cold, clothes made from seal, polar bear, caribou, and sometimes fox or rabbit are preferred for their warmth. There are pieces of clothing that may be knit from a special fiber from the musk oxen called qiviut. For waterproof anoraks and watertight boats, seal skin or walrus hides are preferred. These are made impervious to water with ivalu, thread made from sinew.

And of course, each woman has her own special set of tools to aid her in this venture – she uses a knife called an ulu that can cut through the thick animal hides and stores her needles in a kakpik, or needle case that is often a piece of ivory or hollowed bone that has been decorated. Our kakpik also has a thimble at one end that the Inuit-Yupik woman would use on her index finger to push the needle through the hides.

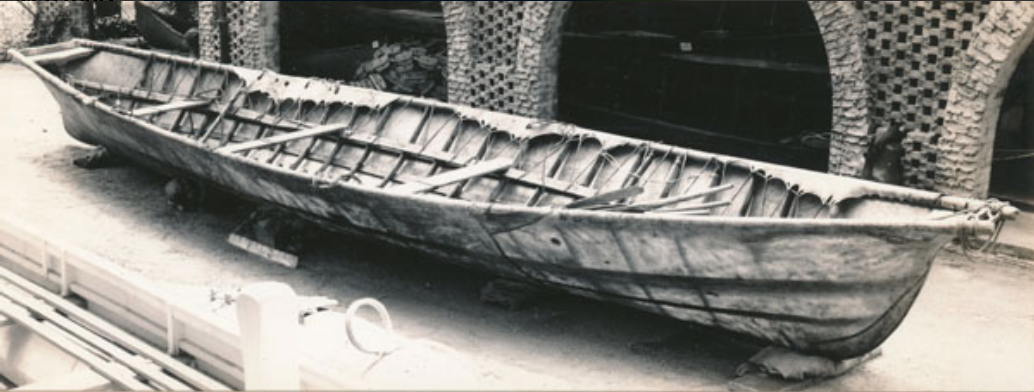

These various skills are put to use and practiced on dolls, which are often sold in a tourist market. Above is an example of a male doll from the indigenous people of Greenland, the Kalaallit. It is imperative to practice construction of men’s clothing as well, because for the Inuit-Yupik, they believe that animals are most attracted to the hunter who has the best tools and is the best dressed, whose clothes and boats are made in a way that honors the animal it came from. A seal who sees a hunter in well-made clothes will willingly give himself to that hunter to be used in an honorable way. And a whale who sees an umiak made from well-treated and cleaned walrus skins knows that he will be giving himself over to honest and generous people.

And the men of the circumpolar north are well aware of how precious the relationship is between women and animals. We can see this on the Inuit marriage proposal below. This delicately carved walrus tusk shows a man hunting a bowhead whale. He and his whaling crew are seated in an umiak covered in the walrus skins treated by his hopeful wife, and he is dressed in skins prepared and sewn by his beloved. And this whale is now giving himself over to this crew because of this – but even though it is the man about to spear the whale, it is the woman who has total control. It is through all of her combined skills that she draws the whale to her beloveds team – her spirit is connected to the whale’s spirit.

Women’s magic indeed!