I’ve always believed that society is like a skeleton and that art is a soul. And within the art world, there are pieces that have a way of making a lasting impression; the artist has added something special – like the secret ingredient in a loved one’s cooking – that unique element you can’t quite put your finger on.

I think that’s why, when you look at Edward William Cooke’s 1856 painting, “Violent Squall on the Adriatic”, it becomes so much more than a painting of a fishing boat, instead it comes to life and plays out like the dramatic climax of a movie.

The Transportive Power of Art

He’s placed us in the churning lagoon with these boats so that we can feel the whip of the wind and the salty spray of the waves on our skin. And we’re there with him, he’s sharing his own personal experience with us.

He’s been in that lagoon, felt that spray and seen firsthand how quickly these storms can arise, and I think he wanted to remember.

Cooke spent much of his life traveling, particularly in Italy and it was one of his strongest influences. Even when he was back home in London, his paintings – like this one – reflected the scenic destinations his heart clearly longed for. The passion that Cooke adds to the painting comes from his upbringing in engraving and art. Both Cooke’s father and uncle were engravers and so he was taught this skill from a very young age and showed immense talent. He was heavily influenced by the Dutch Old Masters, whom he studied during his extensive travels. He was also a voracious learner of ships, boats, and all types of watercraft – in fact, by the age of 18 he had published a book called “Fifty Plates of Shipping and Craft Drawn and Etched by E.W. Cooke”.

This piece, commissioned by Lord Londesborough in 1855, reflects these influences of Cooke’s life experiences. For the most part, Cooke was given free reign – his diary notes that he was asked to paint “a large marine subject”. What resulted was Cooke’s work of passion, one that is known today as one of the most important pieces of 19th century British Maritime Art. And I believe that part of the success of this piece is owed to that secret ingredient.

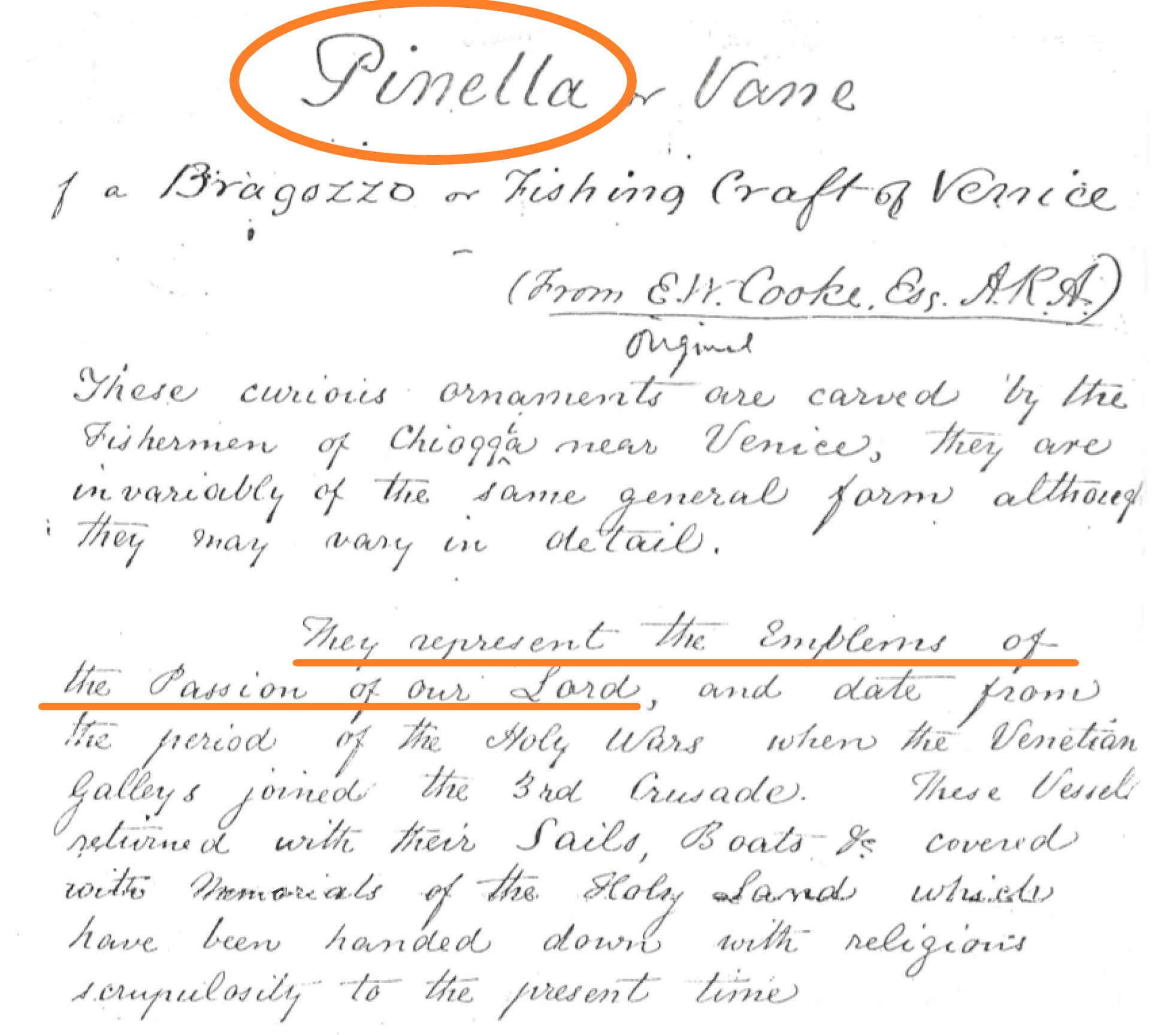

About a Bragozzo

You can imagine that Cooke, enamored by all types of watercraft, would be especially interested in boats like these – they’re called Bragozzi. They’re made in the small region of Chioggia and were used for fishing in the Adriatic sea and shallower waters like those near Venice. The sails are painted by the individual fishermen and are highly personalized so they can be seen from a distance. The pigments are mixed with seawater, applied to the sails, and then left to dry. Once dry, the fishermen drag the sails through the water to rinse the extra pigment off (which I think is a lovely symbolic tradition.)

For this piece in particular, the artist chose a vivid, eye catching sail for the central vessel. The vibrant yellow orange of the sail’s body creates a striking backdrop for symbols both religious and cultural. And this sail is more intricately patterned than the others shown in the painting – an artistic choice that builds interest in this boat above all others, and creates a visual starting point.

By utilizing the rigging lines, Cooke skillfully leads our eye up and out over the lagoon following the nets, which are, themselves, a testament to his technical maritime knowledge as well as his artistic ability. The amount of movement and detail with which the artist painted the nets goes back to his beginnings in etching.

Looking Deeper

Taking the time to look at the artistic elements of a painting is crucial to gaining a deeper understanding. We’ve taken a moment already to look at color and line, but composition- the artist’s careful arrangement of these individual elements to bring balance and unity- is perhaps the most important. A skilled artist, like Cooke, uses these elements, along with that secret ingredient, to transport us beyond the painting’s frame and make us feel like a part of the work: no longer a viewer, but a participant.

Go Beyond the Frame

And can’t you hear it? The creaky groan of this fishing boat is barely audible as the waves crash explosively across the bow and the wind bellows against the sails. Nets are sent whipping dangerously above the heads of the fishermen who are calling to each other, too familiar with these sudden storms but not naive to their danger. We feel the urgency of the impending storm, as the clouds quickly and ferociously barrel in. They seem to push over the boat which rolls precariously in the water as if one more gust might force it to capsize. And every boat nearby, like this one, is making a mad dash for the safety of the harbor that is so close, yet still just a spot on the horizon.

The artist has used composition to split the storyline here – he’s created two narratives, two sides to the same coin, two potential outcomes. The yard, that vertical wooden beam holding the sail on the central boat, has been carefully placed in the middle of the canvas, effectively dividing the composition almost perfectly into two halves. On the left of the canvas we see mostly fluffy white clouds with just hints of the approaching storm. In the background we find Fort Sant-Andrea standing soundly as a symbol of protection and just beyond it, the harbor which the ships lean towards as if being drawn in by the promise of safety.

On the right half of the canvas, darkness shrouds the ships in the background, as if they’re being sucked into the storm. They almost seem to disappear, the creamy white of their sails beginning to take on the same mottled gray of the clouds, the boat barely visible above the waves. The artist has juxtaposed these two scenarios – the safe harbor, and a rough storm – to create a tension that leaves us wondering: “which will be the outcome for our daring subject?”

Symbols are more than just Symbolic

The fishermen in this region knew the dangers of these sudden storms and so, in an act of invocation, they adorned the boat and the sail with various Christian symbols – the most easily recognizable of which are the crosses on the sail. At the top of the mast there’s a funny looking object, according to the artist’s journal, it’s called a Pinella – it represents the Patron Saints of Chioggia – Saints Fortuna and Felice, as well as the instruments of the passion of Christ.

Following the line of the mast all the way down to the waterline, we find a small angel on the side of the boat. At the stern – or the back of the boat – there’s a figure of a woman with a halo, carrying a branch and standing on an anchor in the water – she is the figure of Hope. Barely legible, even up close, there’s a tiny inscription above her, “Noi stiamo sotto divina providenza”, which means “We are under divine providence”.

That isn’t a question or a plea for help, it is a statement. And as we read that inscription, we notice the tiniest sunbeam breaking through the storm-clouds, delicately glinting off the sail, the stern, and the rudder. A glimmer of hope in the midst of a storm.

These fishermen are certain that divine forces are watching over them. Though the symbols are positioned as an invocation to God for safety, especially during storms like these, I think they might have also been a comfort to the likely terrified fishermen.

And of course they’re scared, sure they’re used to these storms, but I mean who wouldn’t be afraid when faced with their potential demise at the hands of sea and sky?

The Secret Ingredient

Do you feel the tension? That division of safety versus danger? Do you hear the crashing and spray of the waves or feel the turbulent wind whirling around you? Do you feel that sense of security radiating from the protective symbols?

Those symbols give not just life but soul to the fishermen – they remind us that they are humans who have fears, feelings, and families. And then, by looking a little deeper, by allowing yourself to venture beyond the frame, this painting is transformed for us into more than just a painting of fishing vessels in a storm – it goes beyond the meticulously accurate depiction of a Bragozzo, beyond a powerful seascape. It becomes the survival story of a few men working together to safely make it home to their families.

Had Edward William Cooke not drawn from his passions, this piece may not have had that spark – that unknown secret ingredient that enabled it to come to life in the incredible way it does. That is what love adds – life, soul, and humanity – that’s the secret ingredient.

Be sure to watch the full episode here and stay tuned for new episodes the first Friday of each month!