Top image: Alfred Goldsborough Mayor. Courtesy of the Mayor Family.

What happens when a zoologist/biologist applies his powers of observation for studying animals to the study of boats? For Alfred Goldsborough Mayor it meant producing a body of work that has given researchers and museums some of the best historic documentation available on the construction of a variety of Pacific island sailing canoes.

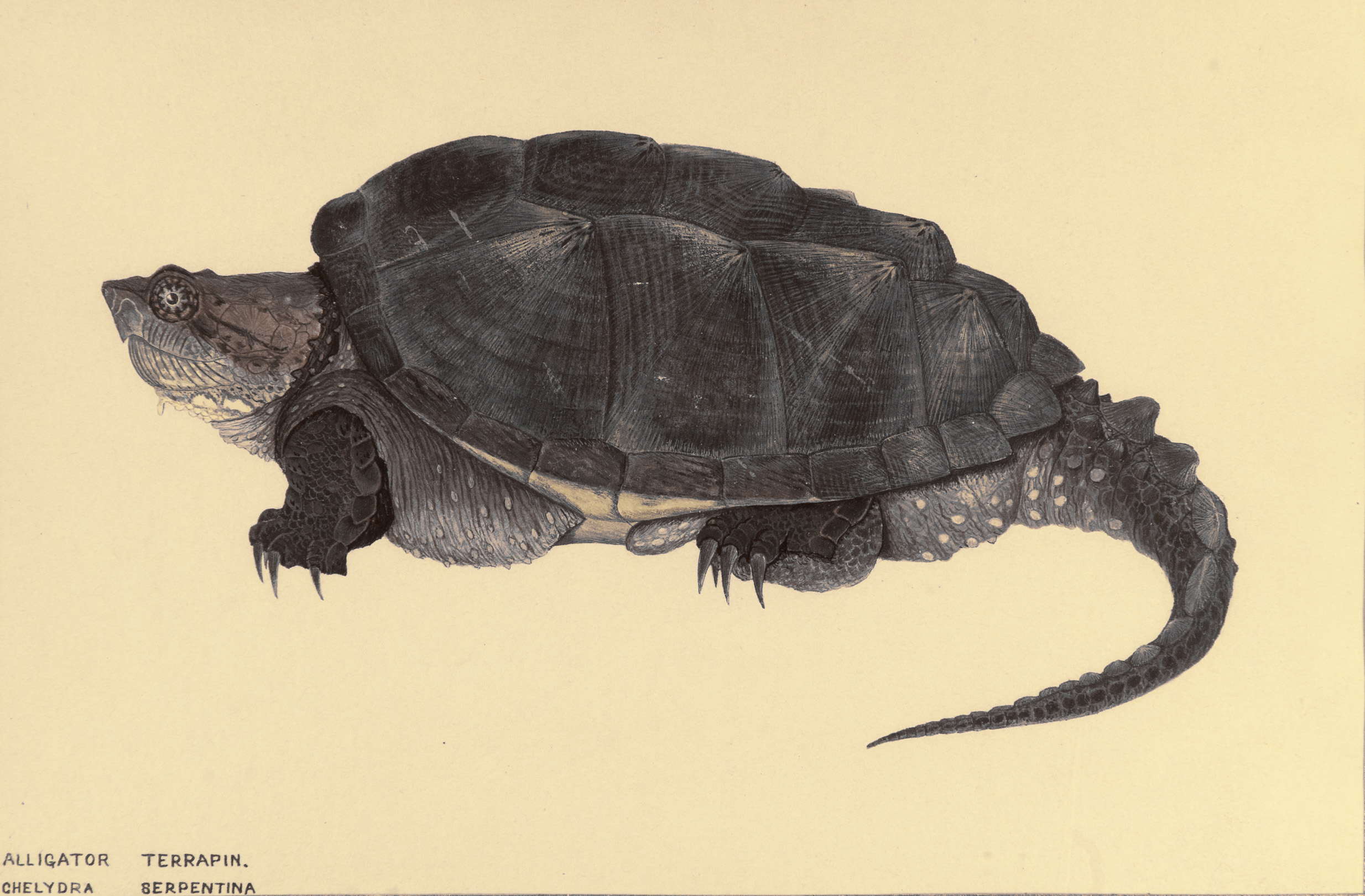

Alfred Goldsborough Mayor1 may not be a name most people recognize but to marine biologists and zoologists he’s world renowned. During his career he authored countless books and articles about land and sea animals, insects, reptiles, coral reefs, museums and education, navigation and a wide range of other topics. His magnum opus, the three volume work Medusae of the World was published in 1910 and became an immediate classic that still retains its usefulness to researchers today. Mayor didn’t just conduct the research and write the descriptions of the jellyfishes, he also created 425 figures and 76 beautiful color plates for the book.

Mayor’s brilliance was inherited, his father was the noted physicist Alfred Marshall Mayer and his mother was Katherine Goldsborough Mayer. Katherine died shortly after Alfred was born but his father quickly remarried and it was his new wife, Maria Snowden, who recognized Alfred’s love of nature and artistic talent and strongly encouraged him to pursue both. Although his father didn’t originally support his career choice, Mayer eventually relented and let the young man pursue his true passion.

In 1892 Mayor began studying advanced zoology at Harvard University and its famous Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), which was under the direction of Alexander Agassiz (son of the museum’s founder famed naturalist Louis Agassiz). Immediately recognizing Mayor’s intellectual and artistic abilities Agassiz invited him to collaborate on a book about Medusae2, Agassiz’s main area of interest. Mayor immediately began studying hydromedusae (small jellyfish), scyphomedusae (larger jellyfish), and ctenophores (comb jellies) and within a few years had established himself as an authority on the animals.

During his time at MCZ, Mayor served as curator of the Radiata collection (animals like starfishes, sea urchins, comb jellies and their relatives). He and Agassiz also collaborated on four articles about jellyfish published in the Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Mayor, of course, supplied the drawings for the figures and color plates. Mayor also accompanied Agassiz on four collecting and research expeditions.3 In 1893 they went to the Bahamas to collect, describe and draw jellyfishes. In 1896 they spent two months collecting around Australia, and for a few months in 1897 and 1898, the team studied coral reef formation in the Fiji islands.

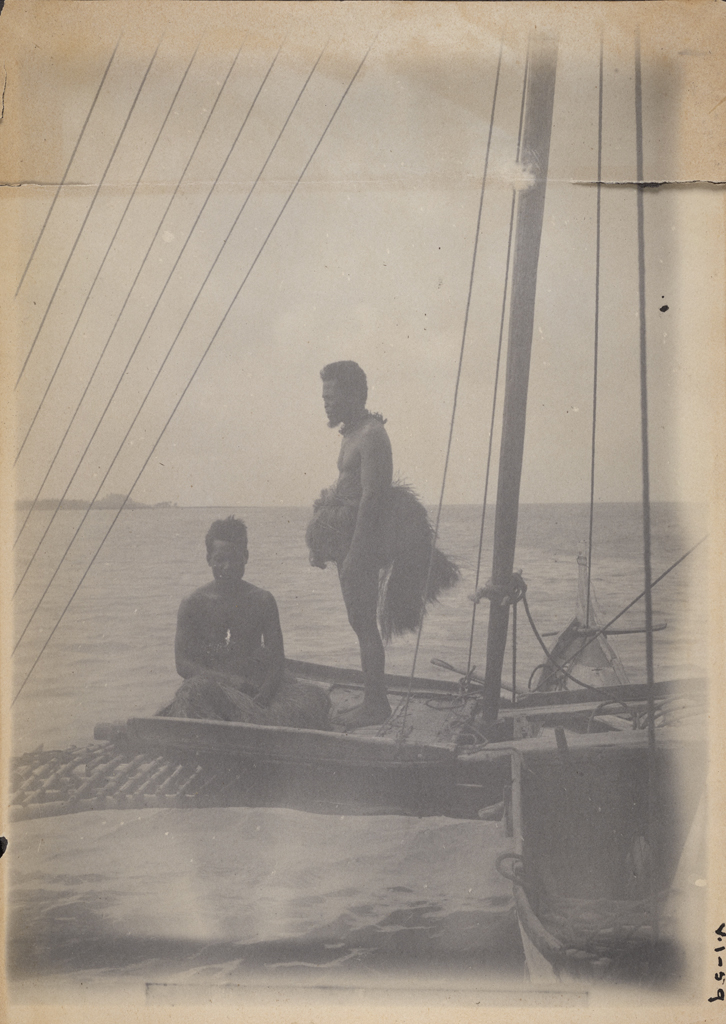

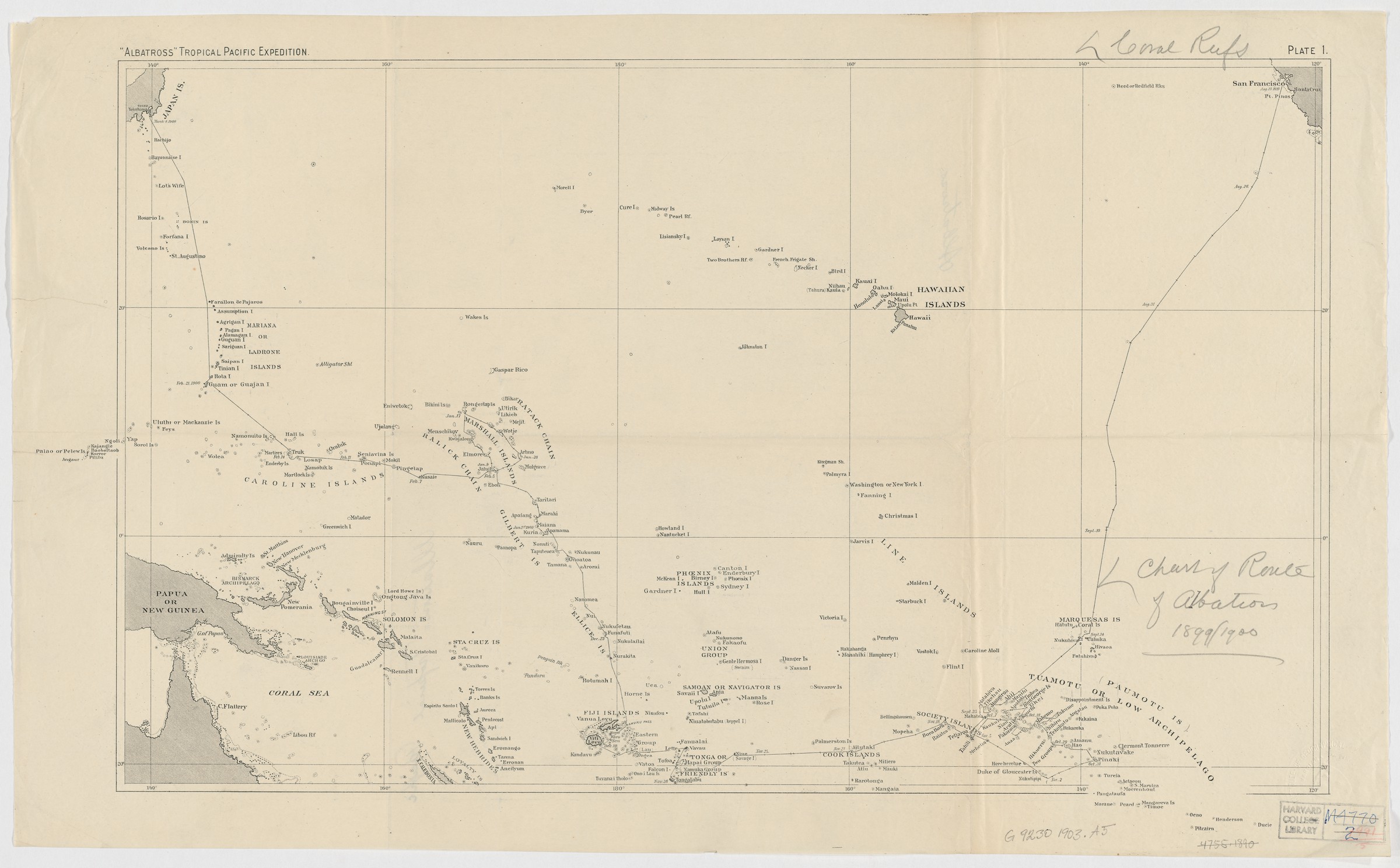

The longest and most extensive expedition occurred between August 23, 1899 and March 4, 1900. The main purpose of the expedition was the study of atoll and coral reef formations, but the researchers also collected and studied marine and land animals, birds and insects. Because the expedition was supported by the US Fish Commission steamer Albatross, some of the expedition’s researchers (apparently including Mayor!) studied fishes and native fishing methods, apparatus and boats. They also collected ethnographic material documenting the art and culture of the Pacific islanders.

During Mayor’s extensive travels he developed a real appreciation of and interest in the Pacific islanders and the 1899-1900 expedition gave him an extended opportunity to study the peoples and cultures on a large number of islands. He eventually published six articles in Popular Science Monthly and Science Monthly on peoples of the Pacific.4

Albatross visited ten groups of Pacific islands and landed researchers at 59 different locations during the eight month voyage.5 Along the way they performed nearly 250 soundings and collected marine animals from various depths by dredging and trawling. Upon arriving at Taiohae on Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas the real work of the expedition began. Along with his regular research, Mayor studied and photographed the islands, the people and the boats. The images he created were used to illustrate the various publications generated from the work of the expedition as well as other specialist publications like The Canoes of Polynesia, Fiji, and Micronesia by James Hornell which was published by the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Hawaii in 1936. That work, now a part of Canoes of Oceania, is on its fourth printing–a true testament of the enduring importance of the work.

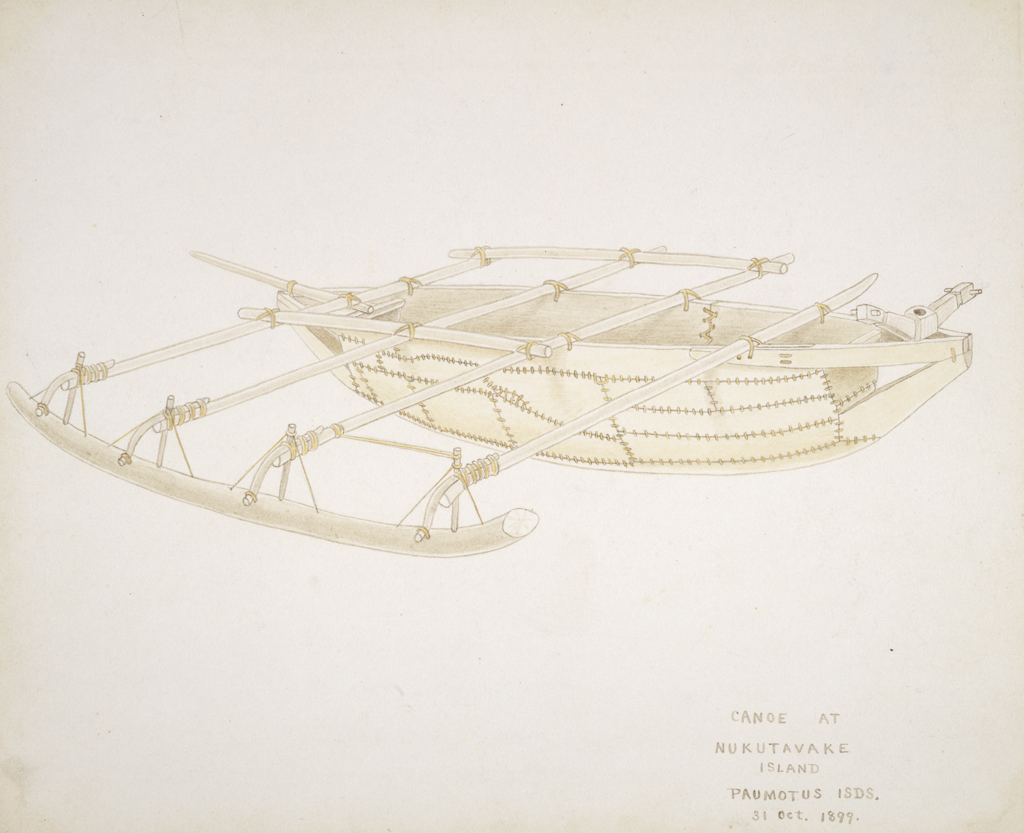

So why am I discussing the career of an eminent marine biologist? Because he’s part of our Museum family, that’s why! In 1900, Alfred married Harriet Randolph Hyatt, Anna Hyatt Huntington’s older sister. Thirty-four years later, while Anna and Archer Huntington were actively involved in the development of The Mariners’ Museum and Park, Alfred’s son and Anna’s nephew, Alpheus Hyatt Mayor, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, donated a collection of ten drawings and twenty-nine photographs created by his father during the 1899-1900 Albatross expedition to the new museum’s collection–and they are amazing!

The first images in Mayor’s collection date from the arrival of Albatross at Nukutavake in the Tuamotu (originally Paumotu) islands on October 31. During their time at the island Mayor and fisheries expert Alvin B. Alexander examined three canoes ranging from 13-½ to 17 feet long. The canoes were made of built up planks sewn together with coconut fiber rope. In Mayor’s drawing, the cleat at the stern is for securing the sheet of the sail and bracing the steering paddle when maneuvering the canoe through the surf. Alexander felt the canoes at Nukutavake were superior in construction to any other canoe they examined (I beg to differ, some of the other canoes they examined were truly fantastic!).

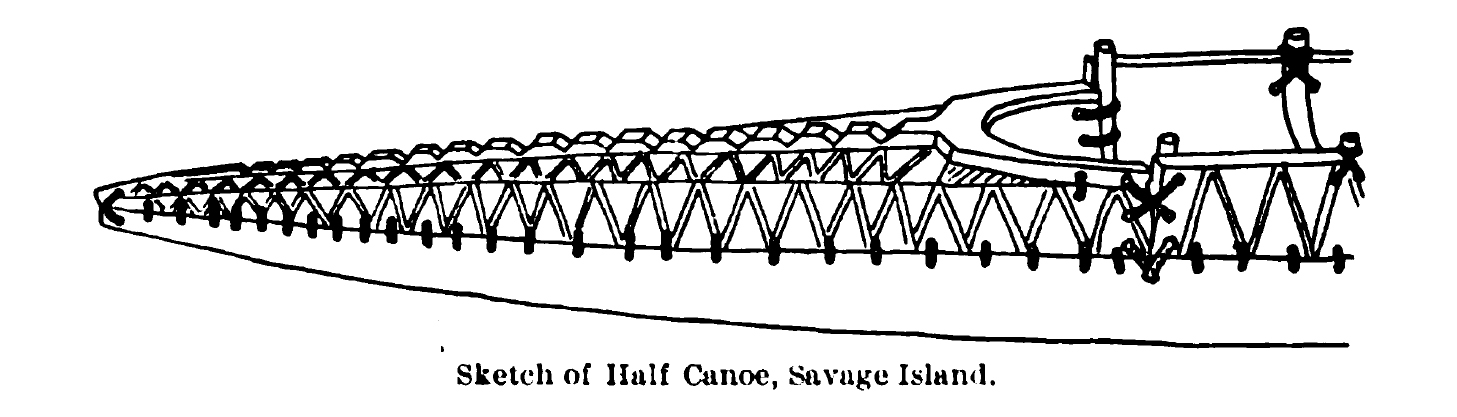

On November 25th while at Niue, Mayor photographed, and may have drawn, a canoe at Alofi, the island’s capital. This canoe was unique in that its bow and stern were covered with decoratively carved covers. It sort of looks like a kayak with an outrigger. Its gunwales were also decorated with a single row of similarly sized sea shells.

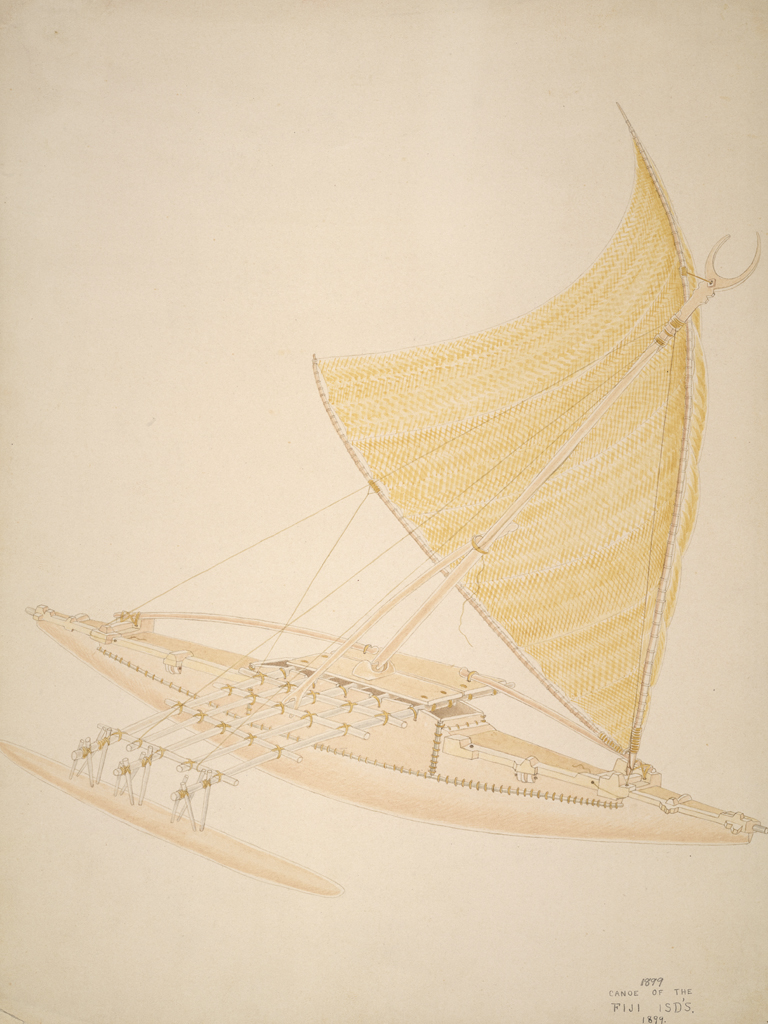

Between December 7th and 19th Albatross visited Kabara island and Suva in Fiji. Mayor and Alexander examined a number of canoes including a Fijian thamakau, a large outrigger canoe used for traveling between islands, and a large double hulled canoe called an ndrua. James Hornell describes the thamakau as “one of the two finest types of sailing outrigger canoe ever designed.” Looking at Mayor’s beautiful drawing it’s easy to see why!

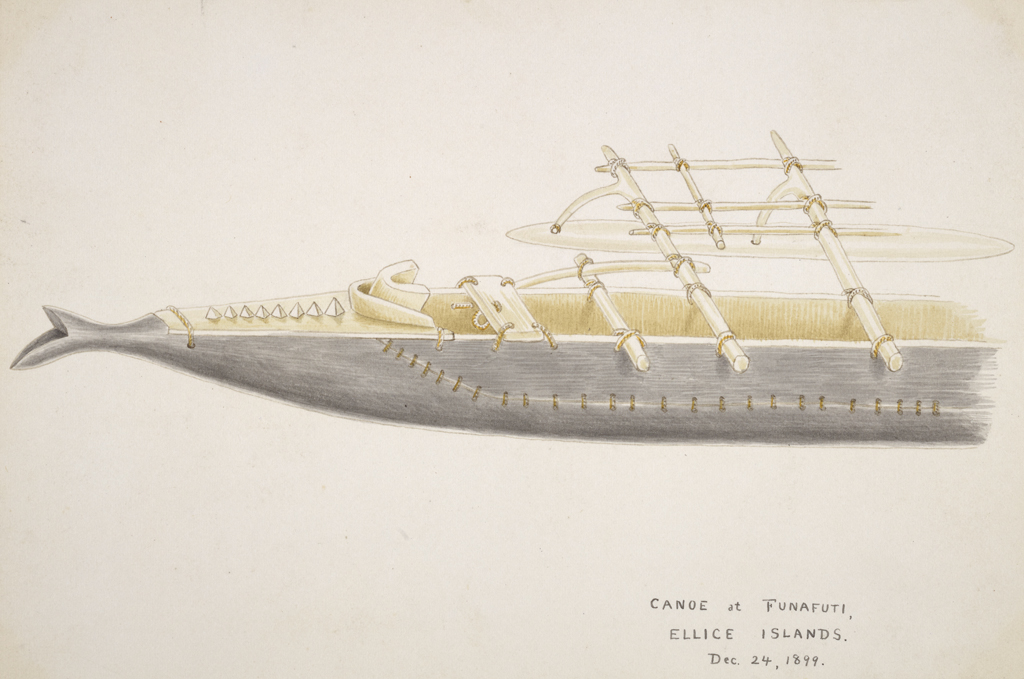

At Funafuti Atoll in the Ellice Islands (now called Tuvalu) a dugout canoe 27 feet long was examined. The ends of this canoe are covered over and the stern cover is ornamented with a line of raised pyramidal knobs. Master canoe builders said the bifid shaped stern represented the gaping mouth of a kingfish. Mayor’s drawing also shows the rest for a bonito fishing pole at the stern. The heel of the rod would fit under the seat/thwart and the shaft of the pole rested within the curved mount–sort of like a trolling rod.

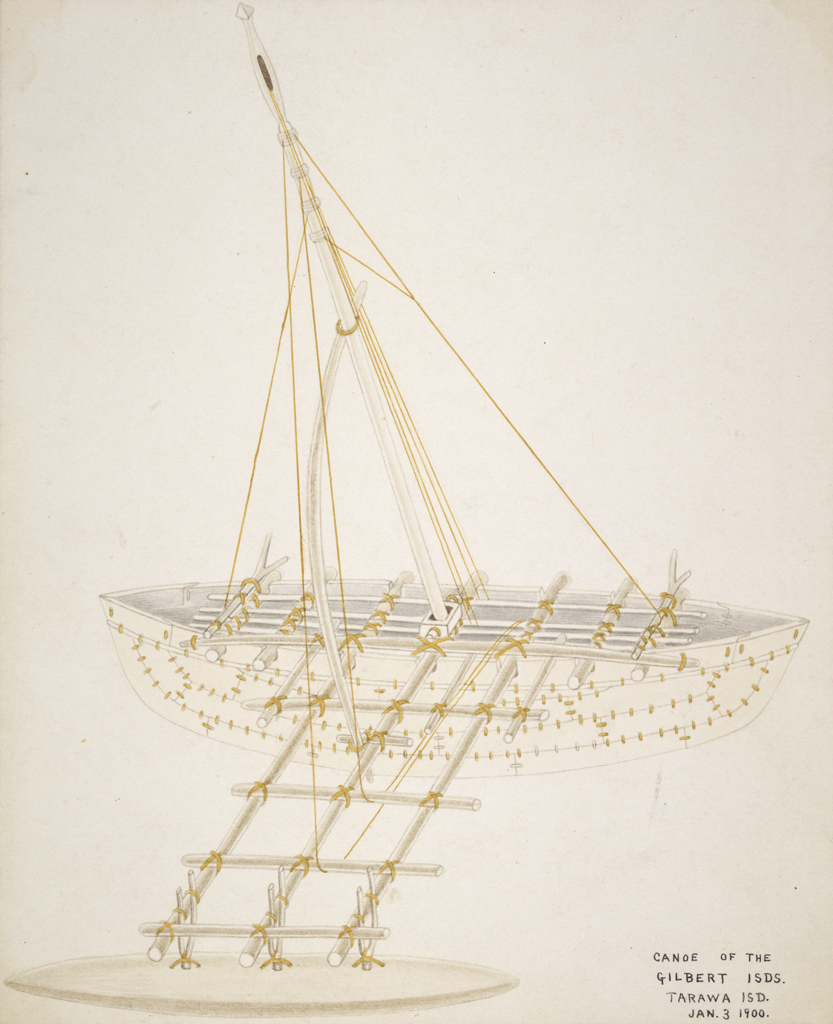

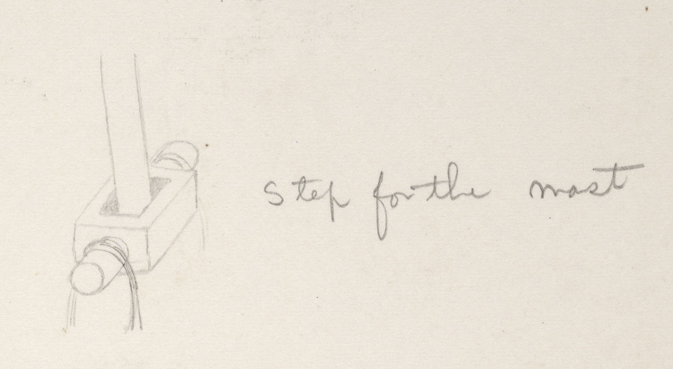

Mayor’s next drawing was created at Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands (Kiribati) on January 3, 1900. It’s the first that illustrates the close attention Mayor was paying to the boats he was documenting. While he provides the comments you would expect (“these canoes are constructed of thin planks tied together with coco-nut fibre sennit”) he also gives a detailed drawing of the boat’s mast step. Most likely, it is because the mast step of the Tarawa canoe was different from those of other islands–instead of being in the bottom of the canoe it was positioned on the top of the middle crosspiece of the outrigger frame.

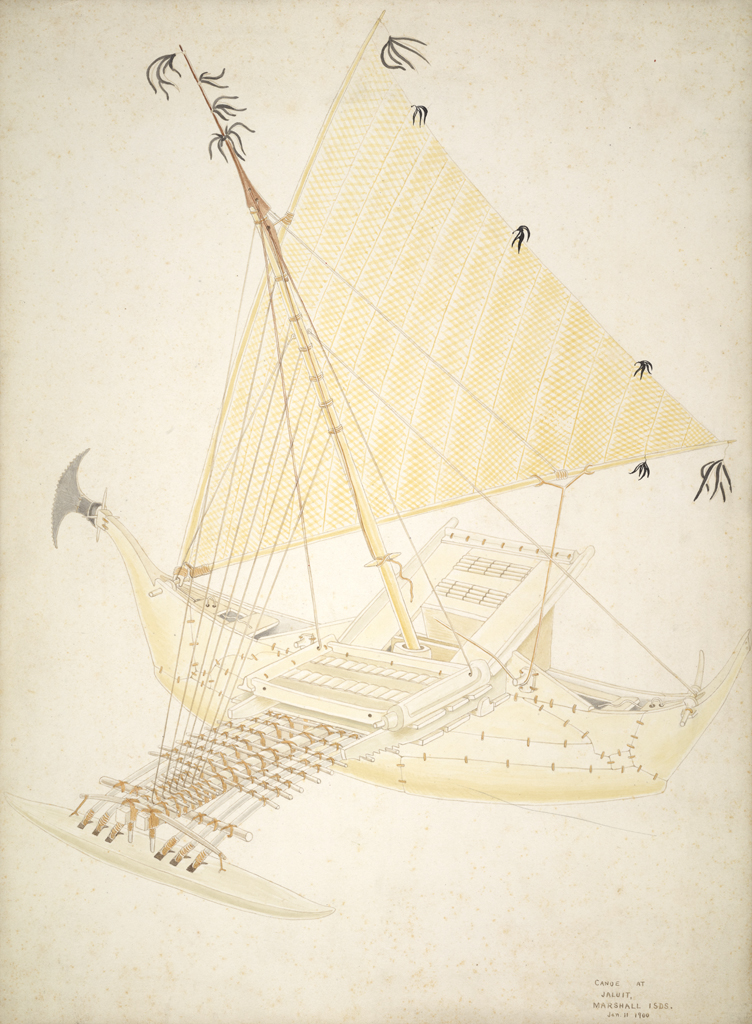

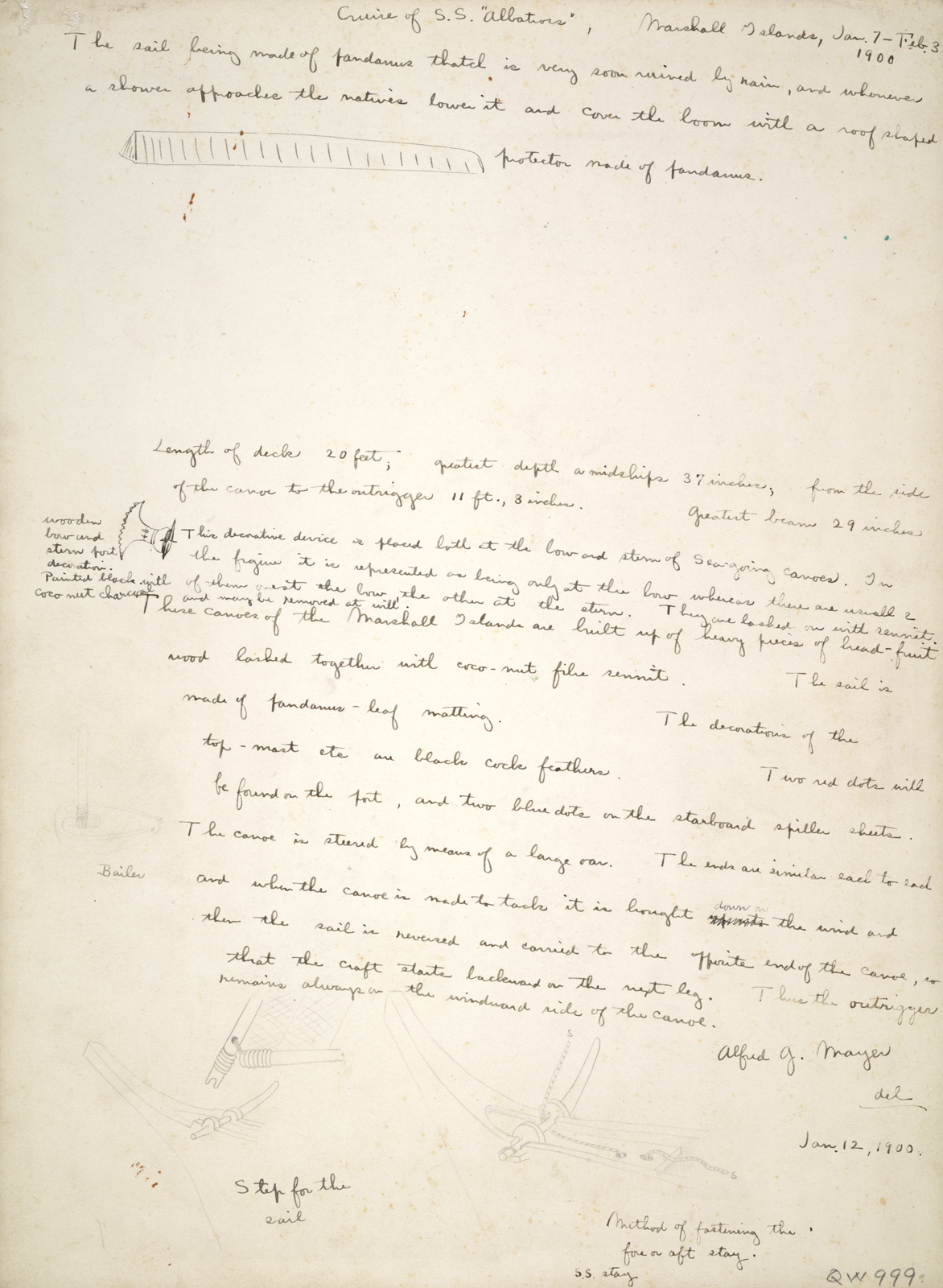

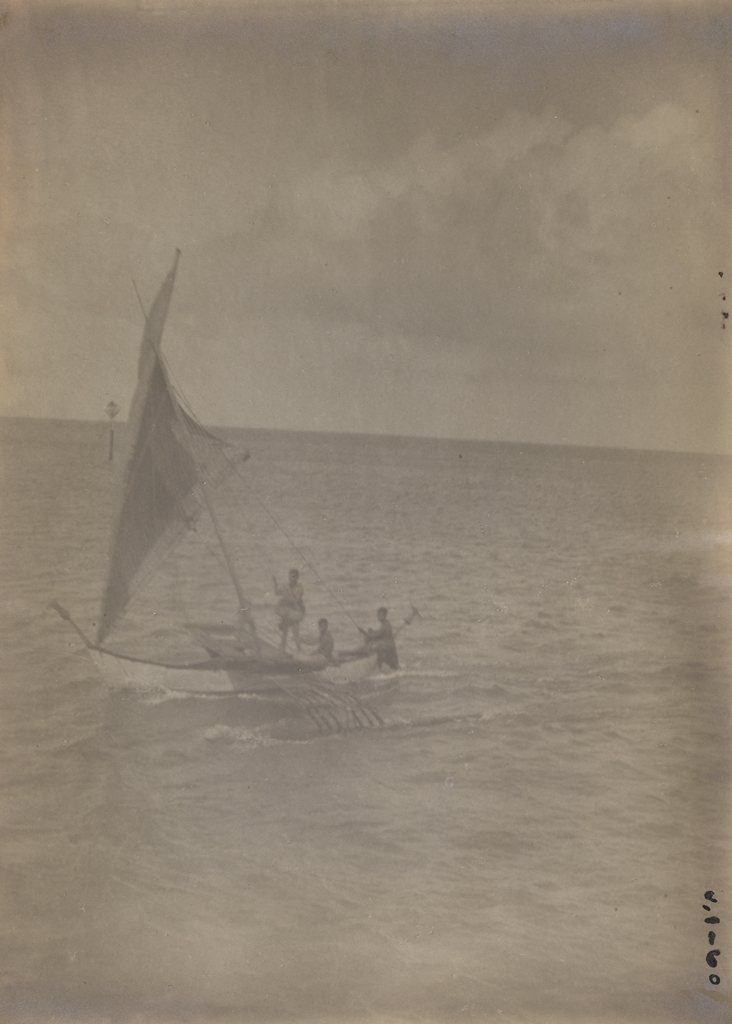

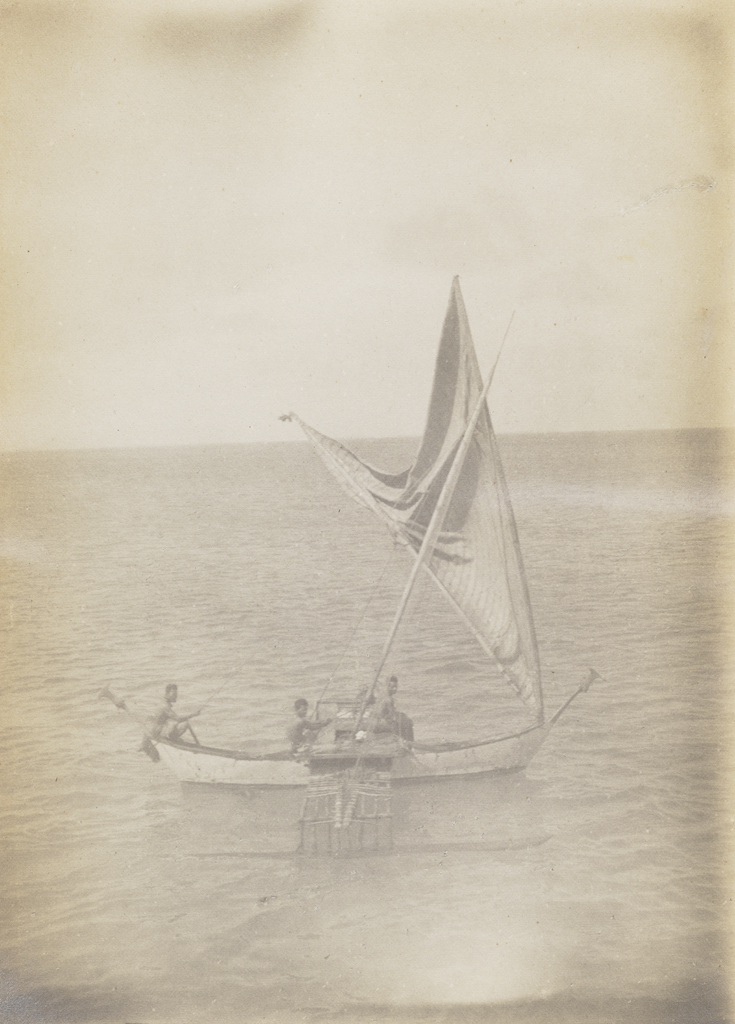

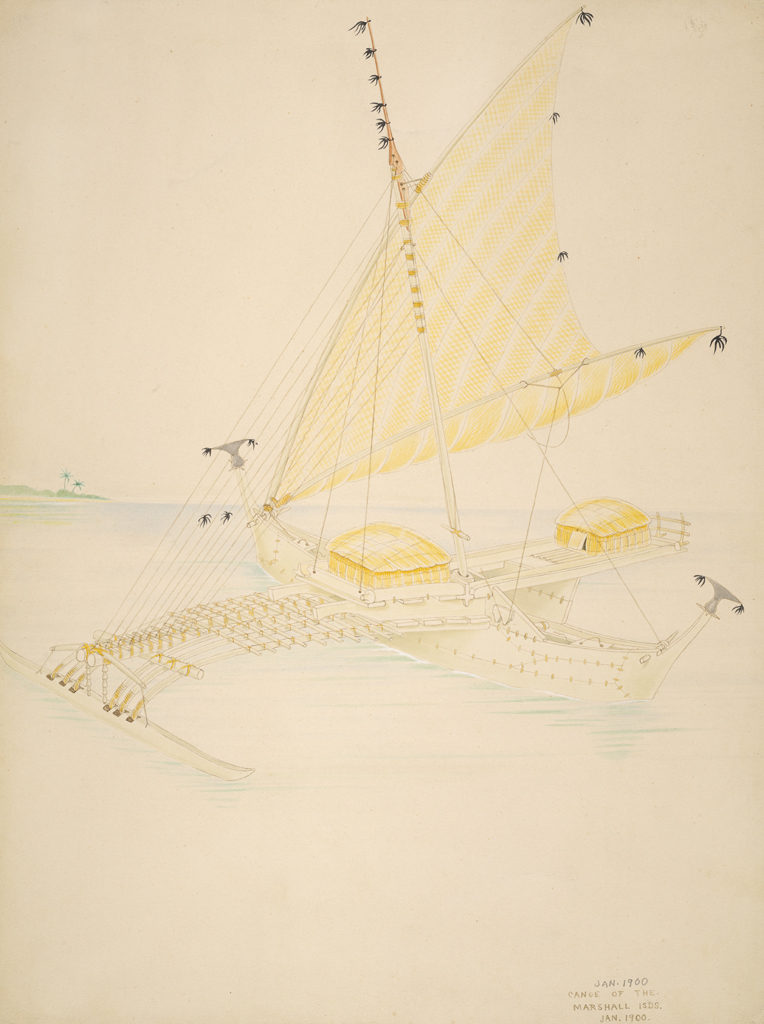

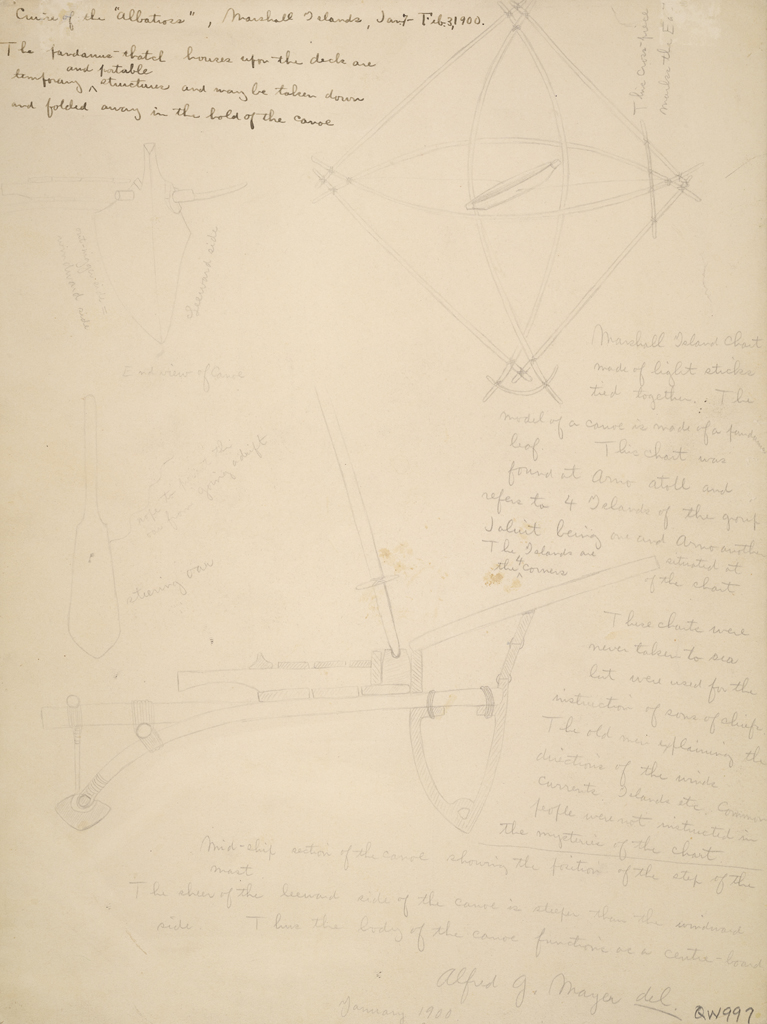

Just a few weeks later Albatross was at Jaluit in the Marshall Islands. The expedition spent five days on the island which allowed Mayor to create one of his most detailed drawings yet. On the reverse, Mayor draws and describes the method of protecting the sail in poor weather, the boat’s dimensions and decorative ornaments, details of the sails, oars and rig. He even documents the outrigger canoe’s most important accessory–the bailer!

Albatross remained in the Marshall Island archipelago for nearly a month so Mayor took the opportunity to draw another, much larger ocean-going canoe. This canoe featured pandanus leaf huts for the accommodation of passengers. When sailing the canoe, one or more men were stationed on the outrigger platform to act as live ballast, moving towards or away from the float to keep the boat balanced as the strength of the wind increased or decreased. On the reverse Mayor drew a mid-section profile so the canoe’s unique hull shape could be easily understood. These canoes have an asymmetric hull; the leeward side is flattened and the windward side is rounded which allows the hull to act like a centerboard.

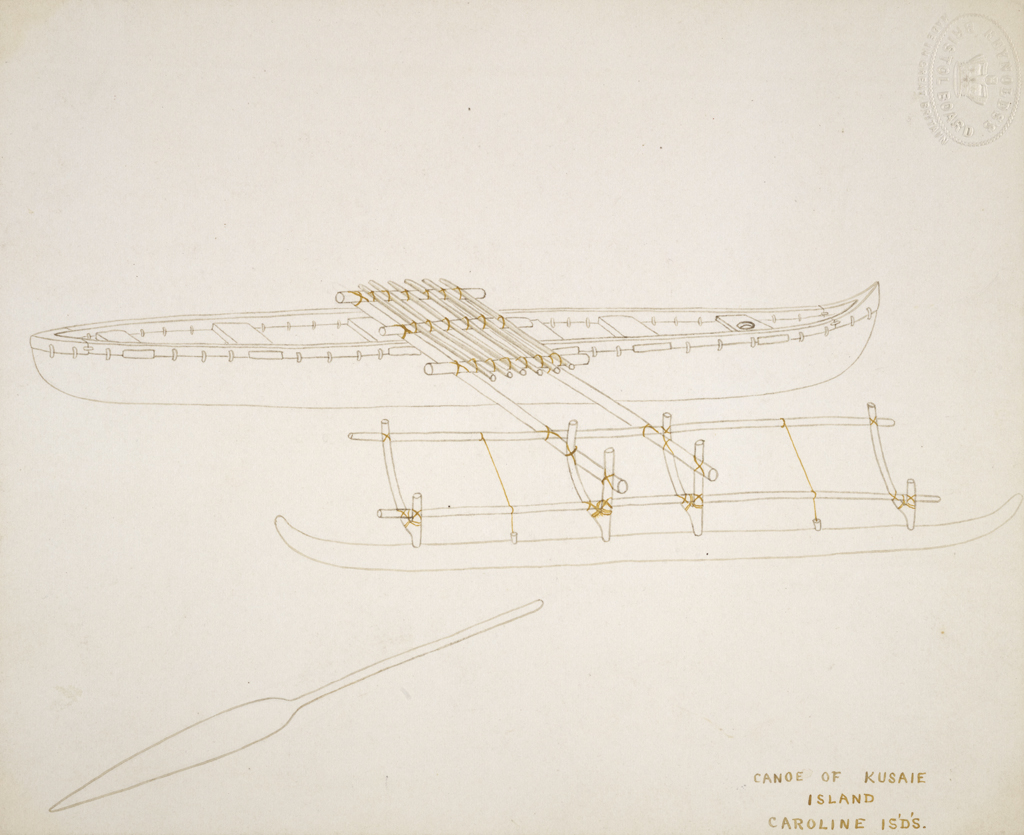

On February 11, 1900 Mayor documented a large dugout canoe on the island of Kusaie in the Caroline Islands. He noted that the “canoes of this island are remarkable for their great length compared to their beam” and that “the canoe only sails in one direction.” Having been steeped in the history and construction of Pacific outrigger canoes for the past few months I must admit to being confused by this cryptic comment until I was reminded that ALL sailboats only sail in one direction. Alexander provides clearer commentary by writing “one canoe was seen under sail, and contrary to other sailing canoe we had seen she was handled in the same manner as a sailboat, that is, she was put about on opposite tacks. This being the first time we had seen a canoe handled in such a manner, we were greatly interested.” He also provides clear reasoning why outrigger canoes are always sailed with their outrigger on the windward side: when the canoe was “brought to leeward the outrigger buried itself” and adds that in windy weather or choppy seas the boat could not have been sailed without danger of capsizing.

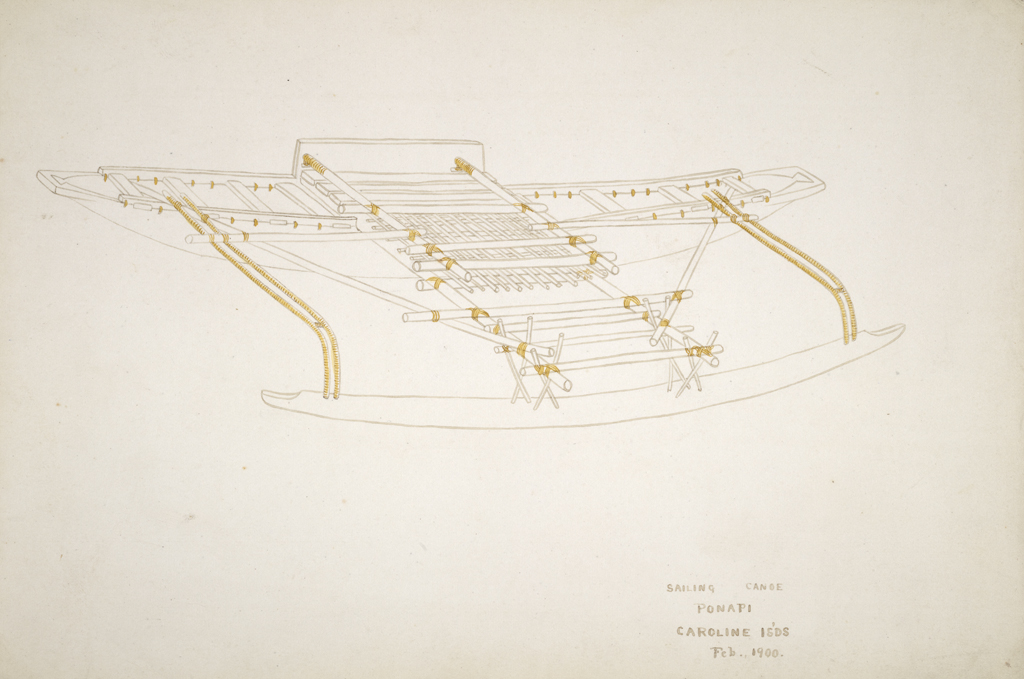

The next day, Mayor documented a dugout canoe in Kiti Harbor on Ponapi (Pohnpei) island. According to Hornell in Canoes of Oceania the Ponapi canoe has “a highly specialized and exceptionally ingenious type of outrigger” that he believed was a survival of the large ocean-going sailing canoes. If you’re super interested to learn about the outrigger on a Ponapi canoe let me know and I’ll send you Hornell’s description–it’s intense!

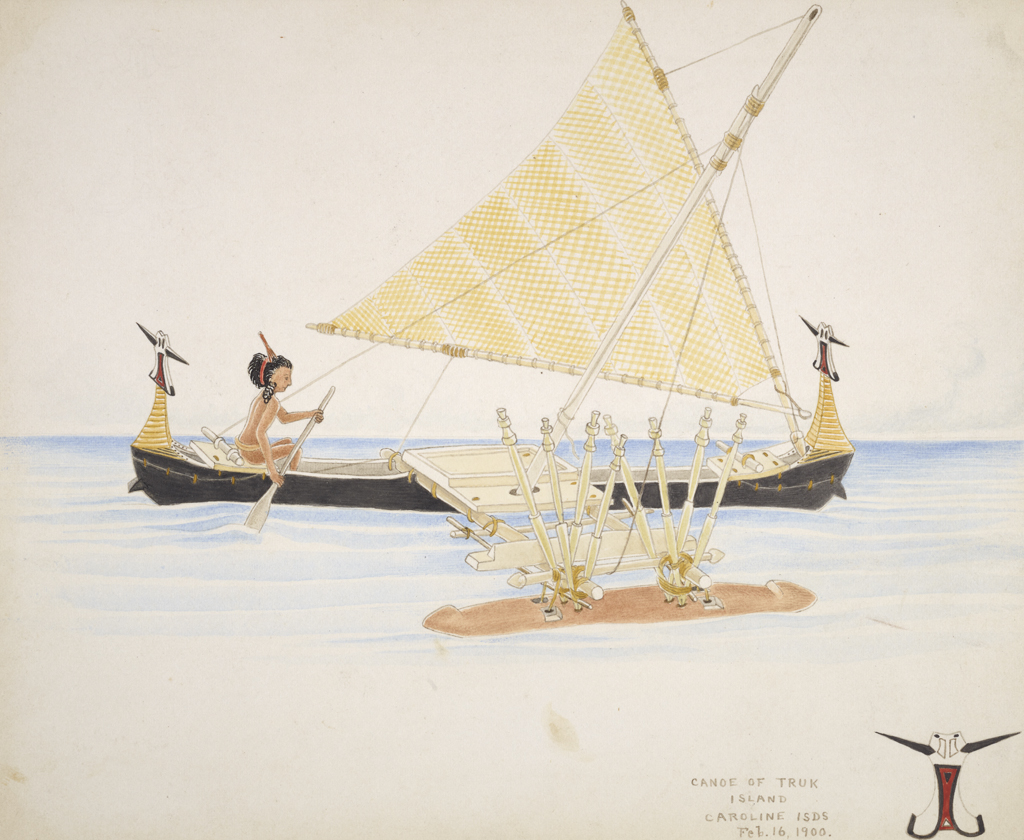

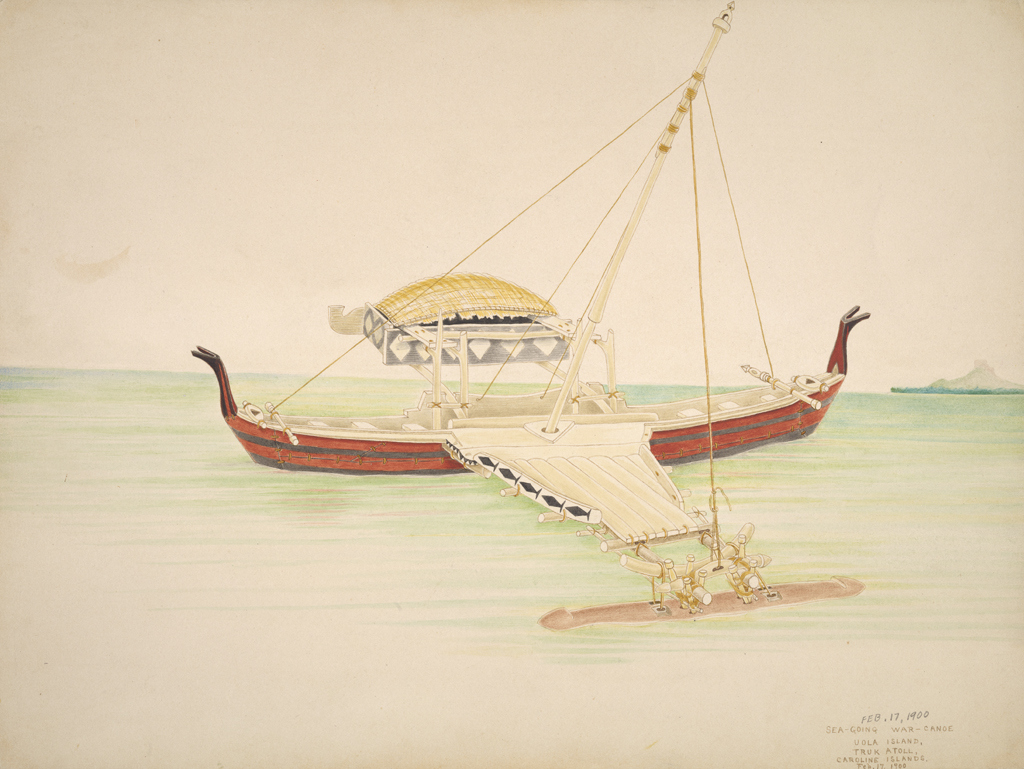

The final two drawings were made at Uola Island (now Weno) in the Truk Atoll in the Caroline Islands. Uola was an interesting place when Albatross visited as all of the neighboring islands were at war with each other. The situation gave Mayor the opportunity to draw two very different forms of sailing canoe: a small paddling/sailing canoe and a large sea-going war canoe. Alexander was struck by the radical difference in the styles of two canoes and commented that if he hadn’t known they were made at Uola he would have thought they “had been made by a people entirely unlike in taste and separated by a long distance.” Both canoes were apparently used for warfare, but the smaller canoe featured decorative ornaments on its bow and stern that could be raised or lowered depending upon the user’s intentions. If it’s raised–watch out! If it’s lowered–we’re cool.

Mayor’s image of a large sea-going war canoe depicts a highly decorated canoe that Hornell believes is probably an ancient type of outrigger canoe. The extensive decoration is a little surprising considering its use, but I guess the Truk islanders intended to impress or intimidate! To be honest, the first time I saw the image I was surprised by how different it was and wondered if Mayor had used a little bit of artistic license when it came to the decoration. I should have known that a biologist’s documentary approach would completely rule out “artistic license.” Luckily, photographs donated with the drawings proved Mayor didn’t elaborate the decoration of the canoe. What a fantastic boat this would have been to see in real life!

Just a few weeks later the expedition ended at Yokohama, Japan and Agassiz and Mayor returned to the United States. On August 17th, Alfred and Harriet were finally married and by November, Alfred had been appointed curator of natural history at the Brooklyn Museum. Just three years later, Mayor became the founding director of the Department of Marine Biology of the Carnegie Institution in Washington and his career and research really took off.

If you’re interested in learning more about this amazing researcher check out the book Seafaring Scientist by Lester D. Stephens and Dale R. Calder.

Bibliography:

Stephens, Lester D. and Dale R. Calder, Seafaring Scientist: Alfred Goldsborough Mayor, Pioneer in Marine Biology. The University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, South Carolina, 2006.

Hornell, James and A. C. Haddon, Canoes of Oceania, Volume 1, The Canoes of Polynesia, Fiji, and Micronesia, Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu Hawaii, 1936.

Alexander, Alvin Burton, “Notes on the Boats, Apparatus, and Fishing Methods Employed by the Natives of the South Sea Islands, and Results of the Fishing Trials,” U.S. Fish Commission Report for the year ending June 1901, pages 743-829.

Footnotes:

1The differences you’ll note in the spelling of Mayor are due to the fact that he changed the spelling from Mayer to Mayor in 1918 to express his disdain for Germany and its actions before and during World War I.

2Prior commitments prevented Agassiz from working closely with Mayor on the publication so the manuscript was eventually returned to Mayor and he was allowed to publish it under his own name.

3The number of research and collecting expeditions Mayor undertook and the number of articles Mayor published during his career are countless! I wholeheartedly recommend the book Seafaring Scientist by Lester D. Stephens and Dale R. Calder if you’re interested in learning more about Mayor.

4Two articles, “The History of Fiji” and “The History of Tahiti,” were multi-part articles that appeared from February 1915 to October 1915.

5The groups of islands visited included the Marquesas Islands; Tuamoto Archipelago; Society Islands (mainly Tahiti); Leeward islands (Maupiti); Cook Islands (Aitutaki); Niue; Tongo (Eua, Tongatabu); Fiji; Ellice and Gilbert Islands; Marshall Islands; Caroline Islands; and the Marianas (Ladrone Islands)