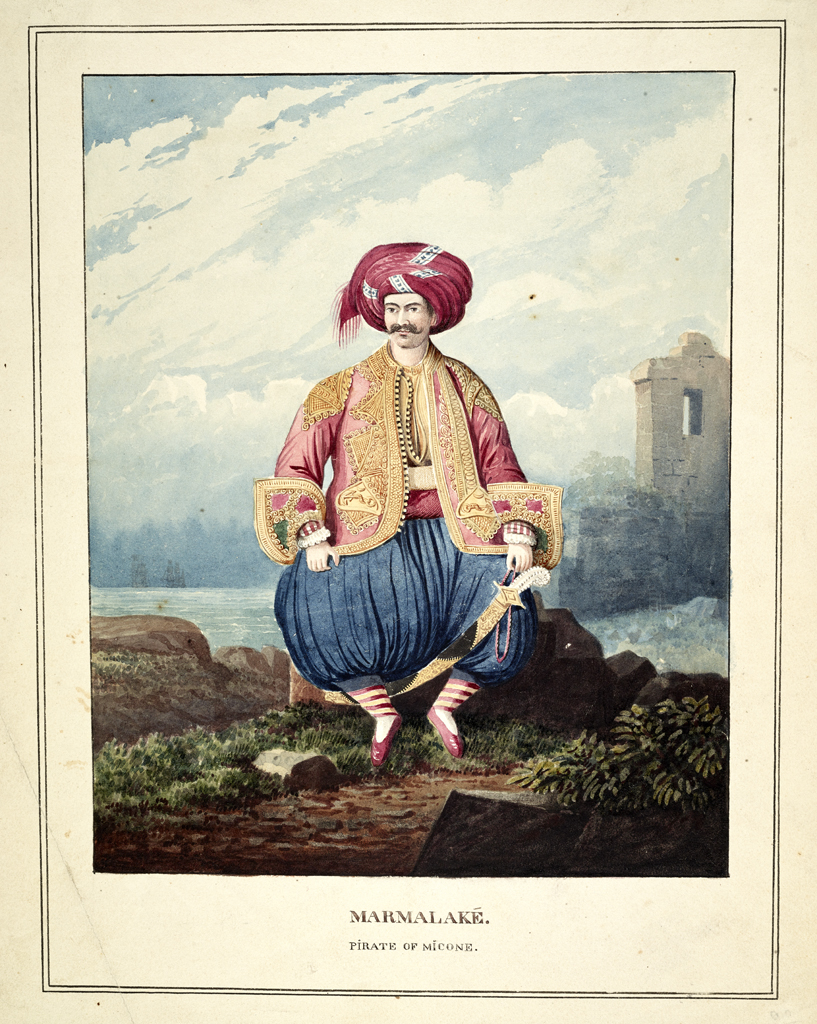

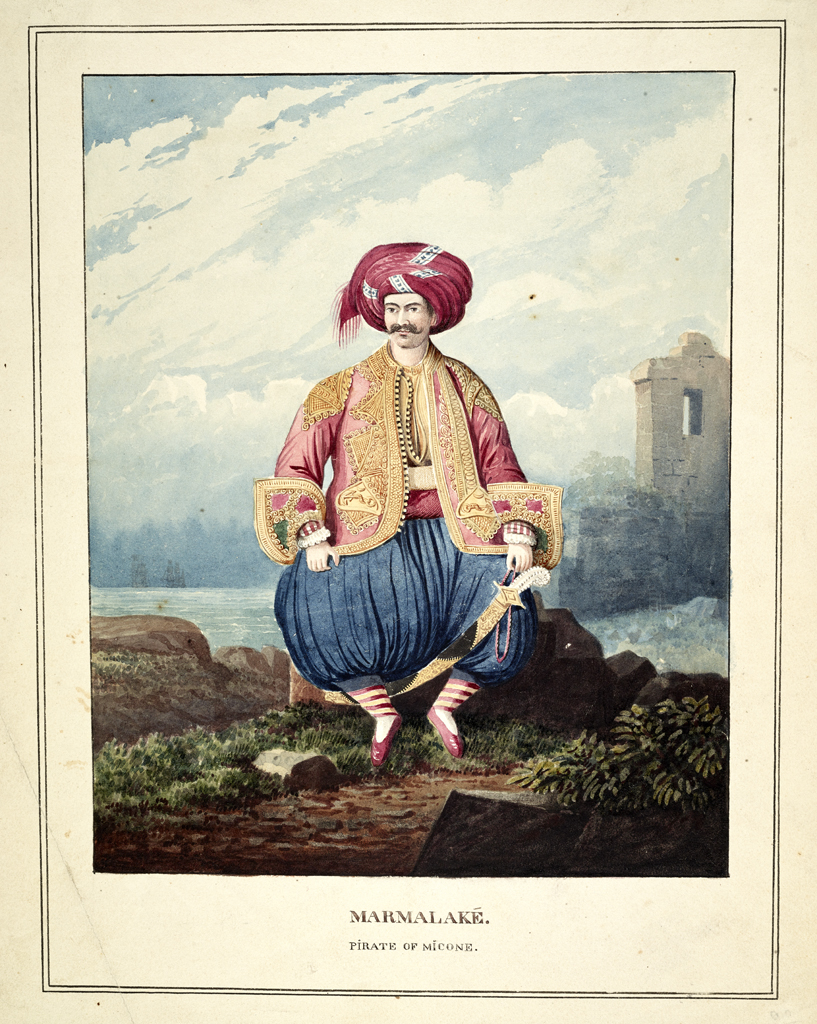

On ‘Talk Like A Pirate’ day in September 2019, we posted a message on Twitter showing a watercolor portrait of an ornately dressed man named “Marmalakè.” The artist had identified him as the “Pirate of Micone.” Our team had some fun with the image and described Marmalakè as a “bucko” and “a meditating pirate.” That odd tweet caught the attention of Antonis Kotsonas, an assistant professor of Mediterranean History and Archaeology at New York University. Antonis was researching the activities of the United States Mediterranean Squadron during the latter years of the Greek War of Independence and believed the portrait might depict a Greek pirate named Manolis Mermelechas.

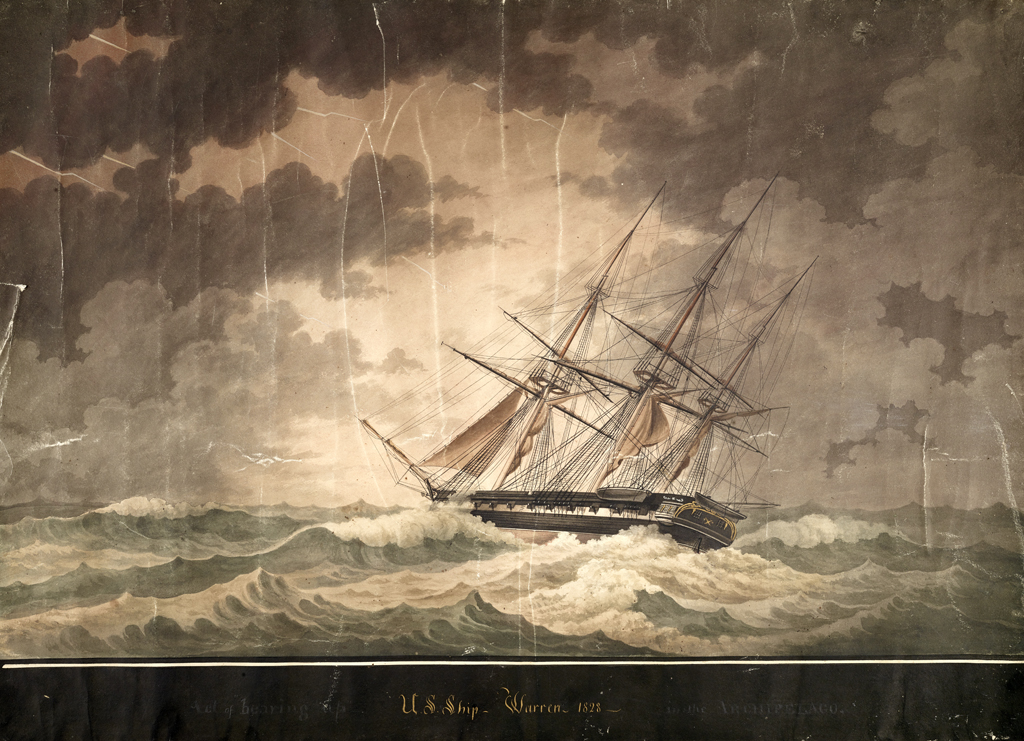

Along with the portrait, Antonis was interested in a group of watercolor landscapes of Greek islands painted by artist Joseph Partridge. The images had been painted between 1827 and 1830 while Partridge was serving as a marine aboard the sloop of war USS Warren. Those years corresponded with the final years of Greece’s War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire. The war had been raging since 1821 and by 1826 had wrought such economic hardship that many Greek seamen had turned to piracy as a form of survival–not just for themselves, but for the communities they lived in as well. In early 1827 Warren, captained by Master Commandant Lawrence Kearny, a man with extensive experience combating piracy, was sent to the Aegean to help protect American merchant ships and conduct antipiracy operations.

Over the course of two months, Antonis and I worked together to uncover the history behind the images and during the process I located information that proved crucial to his research.1 Not only did it definitively confirm the portrait showed Mermelechas, it also revealed recorded, but forgotten accounts of Mermelechas’ piratical activities–exploits that drew the attention of the US Navy and caused the bombardment and invasion of the Greek island of Mykonos. The event was minor but it did make it crystal clear that the United States wasn’t going to put up with any piratical funny business that harmed American commerce. The “attention” seems to have brought Mermelechas’ career as a pirate to an end.

Mermelechas was not a native of Mykonos, he had settled there from the island of Psara after it was invaded by the Ottoman-Turks on July 3, 1824. During the battle to defend his home island Mermelechas commanded four boats manned by one hundred men gathered from Psara and other Greek islands. Many islanders were killed during the battle and the few that did survive quickly escaped from the island rather than face slavery, torture or death at Turkish hands. With their base of operations in Turkish hands, Mermelechas and his men shifted to Mykonos, an island with a long history of harboring pirates.

Eventually, the band’s acts of piracy irritated larger European and Western nations and provoked them into action. Many of them, including the United States, Great Britain, France, Austria and the Kingdom of Sardinia sent warships into the Aegean to protect their commerce. In 1826, pirates on Mykonos were targeted by an Austrian naval squadron under Commodore Filippo Paulucci. The Austrians burned one house and three boats owned by pirates and extracted a fine from the island’s inhabitants. In response to Austria’s antipiracy operations the Greek politician Konstantinos Metaxas, was tasked by the provisional Greek government with suppressing piracy in the Aegean. Metaxas managed to capture “ο τρομερός Μερμελέχας” [the terrible Mermelechas] and a number of other pirates and burn several pirate vessels on Amorgos. To his disappointment the pirates were quickly released with letters of amnesty provided by the government.2

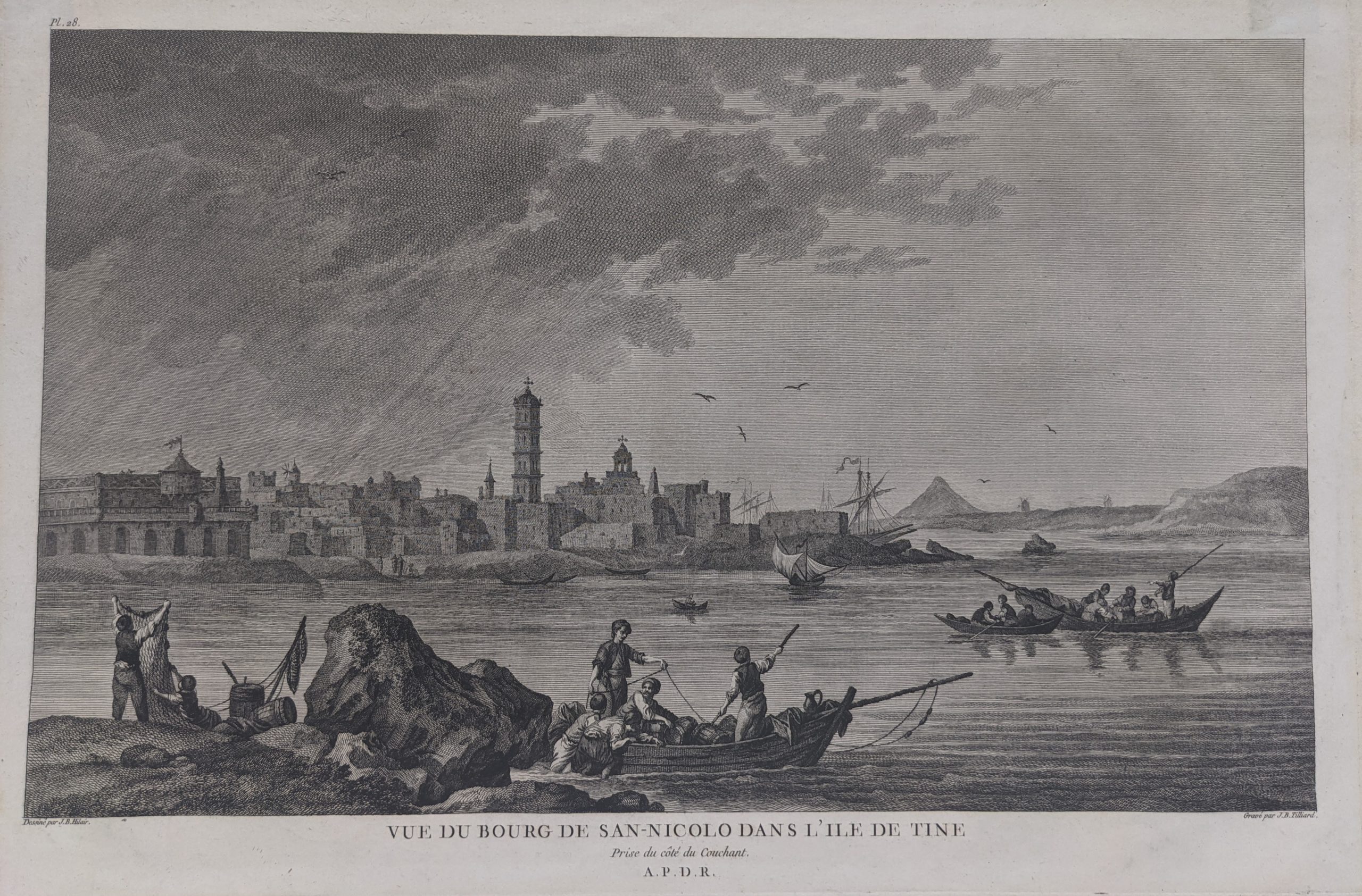

The arrest obviously didn’t stop Mermelechas and the other pirates for long. The acts of piracy continued and even increased. A letter from Smyrna dated November 10, 1827 indicated that in the month of October alone “upwards of sixty vessels have been captured and unloaded.” The captain of the American ship Phoebe Ann, which was traveling from Smyrna with a convoy of forty-three vessels, reported that the passage between the islands of Tinos and Mykonos was “lined with piratical boats.” Overnight several ships in the convoy disappeared and it was feared they had been taken by pirates. Phoebe Ann made it as far as Kythera before she was taken.

In mid to late October it was learned that three American ships, Cherub, Rob Roy, and Susan, and an unidentified English schooner had been attacked. The four vessels had left Smyrna on October 10th in a convoy guarded by USS Porpoise but had been separated from it by poor weather on the 15th. The next day, in the passage between Tinos and Mykonos, they saw eight pirate vessels pulling towards them. Captain Loring of Cherub fired on the pirates but it didn’t intimidate them in the least. As they watched, Rob Roy and the English schooner were surrounded and captured. The crew of Cherub, fearing they would be massacred for firing on the raiders, took to their ship’s boat and pulled as fast as they could for the brig Susan. Luckily, a breeze picked up and Susan managed to escape. The unmanned Cherub was taken by the pirates and sailed to Delos and then Syros (although her cargo seems to have ended up spread from one end of the Aegean to the other!). A short time later the American brig Jane, which was loaded with provisions sent from the United States to relieve the suffering Greeks, was plundered of about 200 barrels “by those whose countrymen she was bound to relieve.” This rampant, unrepentant, and seemingly uncontrollable piracy raised the ire of the United States Mediterranean Squadron and its most ardent piracy fighter, Lawrence Kearny of USS Warren.

During the summer and fall of 1827 Kearny and Warren had been actively escorting convoys; patrolling; chasing; searching; and capturing suspected pirates. In late October Warren captured a boat with fourteen “well-armed” men and one boy and a new 180-ton brig off Grabusa (Crete). The ship chased two other vessels off Cuigotto and Cape Spada and seized, but later released, a third vessel because it matched the description of the ship that had robbed Cherub. Although it hadn’t, a Turkish prisoner on board indicated the crew had recently robbed a French brig. A few days later Warren assisted an Ionian brig robbed of everything (again, even being Greek didn’t save you from Greek pirates!) and pursued and sank a pirate brig at Kimolos.

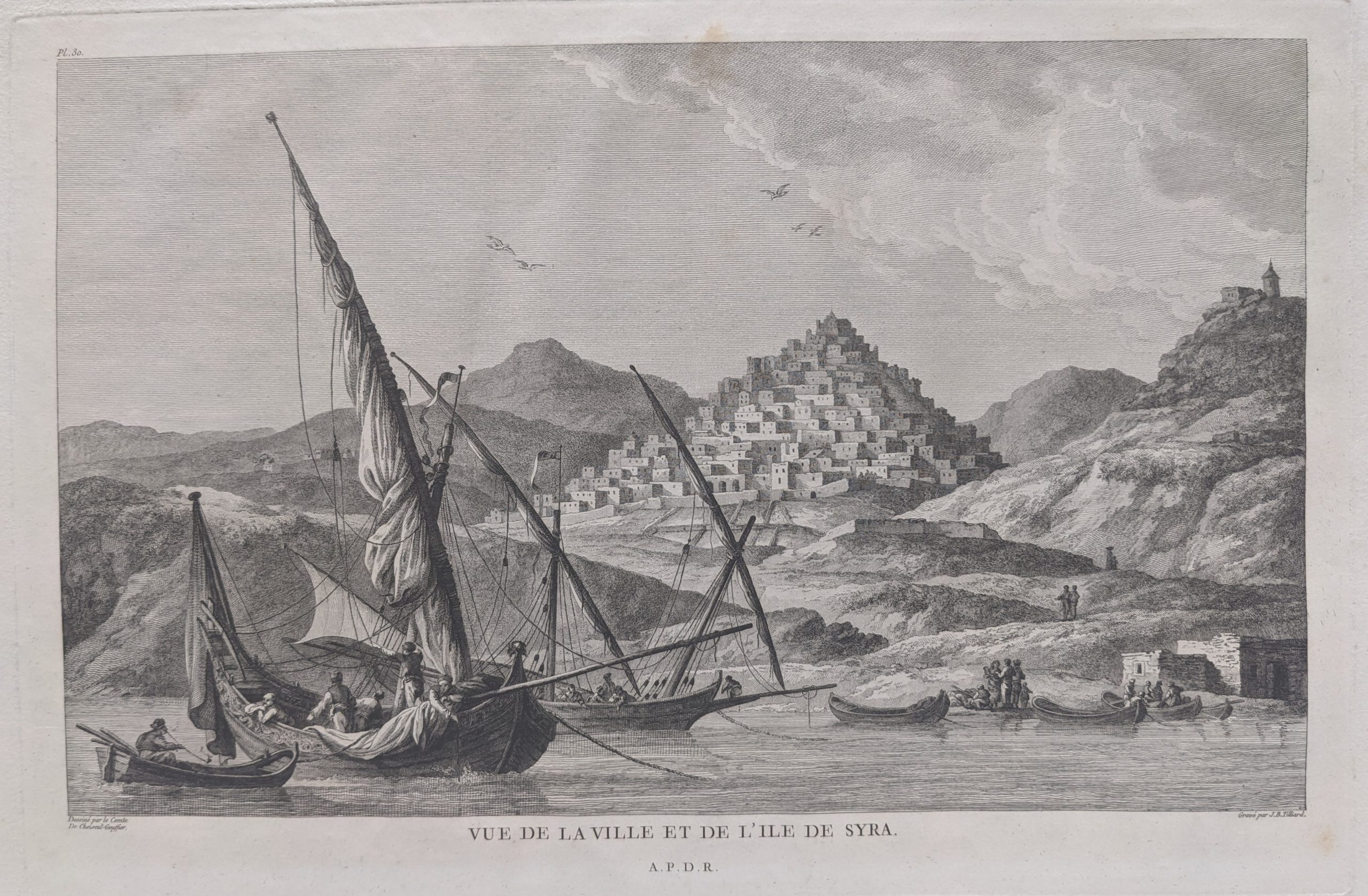

Kearny found the plundered and abandoned Cherub in the port of Syros and took possession of her before sailing for Mykonos. Between Tinos and Mykonos the Americans discovered the aimlessly drifting Austrian brig Silence, which had been robbed of everything–cargo, sails, rigging; even the men’s clothes. Warren towed Silence back to Syros and sailed again for Mykonos. (By this point it’s easy to imagine that Captain Kearny was pretty irate.)

When Warren arrived off Mykonos on October 31, 1827 the Americans began their operations with the capture of a large forty-oared mistico and a search of all the vessels anchored in the port. Shortly after arriving Kearny sent a letter to the island’s leadership ordering them to report on board Warren to provide an “immediate explanation and full atonement” for the acts of piracy and murder perpetrated against American citizens by the island’s inhabitants. The letter also demanded the return of all stolen property. Non-compliance, Kearny said, would oblige him “to use that force which is at my disposal.” In response to the threats, sails and rigging, a few drums of figs, two cases of opium, and some other materials from plundered vessels were sent to Warren. The inhabitants also turned over four men suspected of piracy.

The conflict escalated the following day when Kearny deemed the assistance provided by the islanders insufficient. He urged them to reconsider their level of cooperation by firing several of Warren’s 32-pound cannons over the town. A short time later three more pirates and a few more sails were handed over, but Kearny still felt the islanders were dragging their feet and making promises they never intended to act upon. From the tone of his letters, even those drafted but not sent, it’s clear that Kearny was incensed at the islander’s collusion with the pirates. In a draft of one letter he threatened to seize the island’s leadership, hold them captive3 and demolish the town if the “chief pirate,” Mermelechas, was not surrendered.

Thankfully a full scale bombardment never transpired, but Kearny did show his resolve by again firing the ship’s cannons over the town. Just to make sure everyone knew he was serious, several shots were landed in the town damaging two or three houses (no one was killed). Kearny also sent several bands of armed marines and sailors ashore to search for pirates; take possession of any boat thought to be used by the pirates and burn them; and seize all looted objects they found. The Americans arrested several pirates, other than those turned over by the island’s inhabitants, and supposedly tortured at least one in an attempt to learn where the booty and Mermelechas were hidden. This time, merchandise and personal items plundered from many different vessels, not just Cherub, Rob Roy and Silence, began flowing onto the American warship.

Still hoping to capture Mermelechas, Kearny offered rewards to anyone providing useful information on his whereabouts. He even tried to bribe one of Mermelechas’ men but the offer was “rejected with contempt.” Even Warren’s crew were frustrated at the inability to find the man, stating “pursuit has been unceasing…[he is] everywhere talked of but nowhere seen.”

By November 5th Kearny must have felt they had done all they could to recover the stolen materials and capture pirates and piratical craft. Before leaving Kearny “encouraged” the leadership of Mykonos to do everything in their power to stop the “frequent depredations upon American commerce” and to send any persons engaging in piracy and any recovered property to the American consul. He closed his letter with a warning: “the extent of this system of piracy found to exist among the people is now ascertained and a careful watch will be kept over the transactions in this quarter of the Archipelago.” In other words, I know what you’re doing and I’m watching you.

Warren sailed the following day having recovered 174 drums of figs, two cases of opium, a wide range of other materials, and a handful of pirates. After searching the neighboring island of Tinos, Warren sailed to Syros and loaded the recovered cargo aboard Cherub and returned Silence’s sails and rigging.

News of the action and praise for Kearny and his tireless and effective pursuit of Greek pirates was reported in several newspapers. Letters from Smyrna stated: “a few such men as Captain Kearney, in the Warren…has frightened the Greeks more than all the allied fleet” and “there have been no Piracies for a long time in the Archipelago. Capt. Kearney is almost adored in the islands, for having driven away the Pirates from Miconi, Andros, &c. He has done more good than all the Navies that have been stationed here put together.” David Offley, US Consul at Smyrna, told Kearny he “did more to protect American commerce, and to punish those who molested it, than all the others put together; this is not only the opinion of the Americans, but of all nations, including the poor Greeks themselves.”

Although the correspondence makes it seem as though Greek piracy was stopped in its tracks, that’s not entirely true. By July of 1828 Kearny and Warren were back in Mykonos to address the continued looting of American ships by pirates from the island. This visit was much more peaceful because Kearny attempted to solve the problem by working through diplomatic channels. It was probably during this much calmer visit that Partridge painted his portrait of Mermelechas.4

According to Antonis, piracy in the Aegean was completely crushed by the end of 1828 thanks to the combined efforts of the Western European, American and Greek navies. Offley, in a letter dated October 7, 1829, gives Kearny much of the credit for ending Mermelechas’ piratical career, stating “the breaking up by you of the piratical establishment at Miconi was one amongst the many important services you rendered…”.

Mermelechas remained in Mykonos and the traditional folklore of the island says that after the war he ran a bakery and tended the island’s cemetery. Whatever Mermelechas did during the war, right or wrong, he has remained a well known figure in Mykonoian history. It also seems clear when looking at Partridge’s rather reverential portrait and reading the article published in the New-England Galaxy, that even American sailors were, to some extent, enthralled by the man’s daring exploits and held a certain amount of respect for the man.

But, by 1828, he seems to have been a ‘bucko’ no more. Make sure to check out my next post when I tell the epic story of how Mermelechas “acquired” his wife!

Footnotes:

1 Antonis recently published his article in the Journal of Modern Greek Studies (volume 39, number 2, pages 273-306). It’s titled “The United States Mediterranean Squadron and the Greek War of Independence: A Study of the Standoff on Mykonos and the Pirate Mermelechas.”

2Mermelechas and other pirate leaders stated they were trying to force European nations to recognize Greek independence with their acts of piracy. They were probably forgiven because the piracy helped acquire materials that supported the war effort and the economies of the communities they operated from.

3Kearny actually did hold to this threat. The island’s governor and other authorities were seized and held on the ship for three days while Warren’s crew searched the island.

4My reasoning for this statement is this: in an article titled “The Pirate of the Archipelago,” published in the New-England Galaxy and United States Literary Advertiser on April 25,1828, a man identified as “Paul Jones Jr.” (who Antonis and I believe is actually Joseph Partridge) states “Large sums have been offered to discover them. Pursuit has been unceasing and in fact they are everywhere talked about but no where seen.” This certainly seems to indicate the writer never put his eyeballs on Mermelechas in November. Perhaps by July Mermelechas had stopped his depredations and wasn’t worried about being seized by Warren’s sailors and was willing to have his portrait taken.