In my last blog, I wrote about a rare Confederate imprint map that was donated to the Museum by descendants of William Henry Irby.

Now, thanks to information and images provided by the family, I can relate the story of his Civil War service.

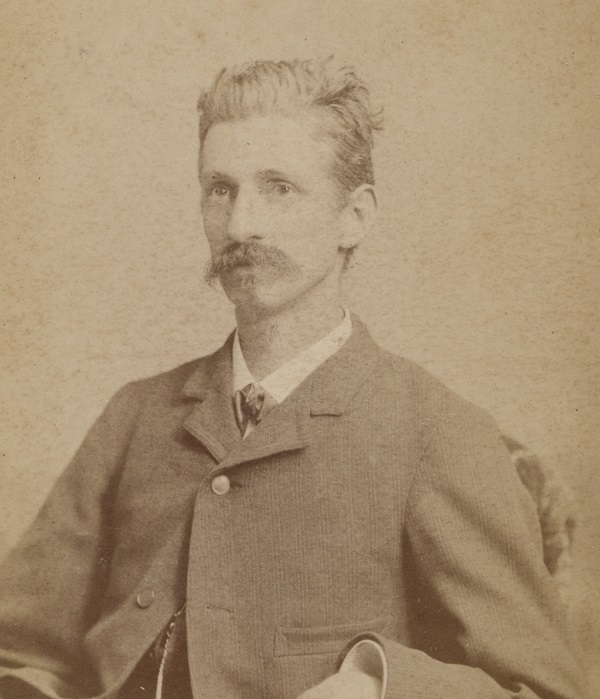

William Henry Irby was born on November 6, 1819, in Pittsylvania County, Virginia, to Thomas W. Irby and Ona Oney E. Thurman. William was one of 11 children born to the couple. Raised on a farm, he married Phoebe Ellen Hubbard, the daughter of the Reverend Joel Hubbard, in 1858. They settled on a farm in Pittsylvania County.

Following the outbreak of the Civil War, William Irby took leave of his wife and child and reported to Norfolk for military duty. In a letter to Phoebe written on March 30, 1862, he writes that “a large number [of] the forces here will volunteer if they are allowed to do so.” He goes on to write that “we are expecting a fight here at almost any time and while I am writing this letter the cannon are roaring like thunder in the direction of old point [Old Point Comfort].”

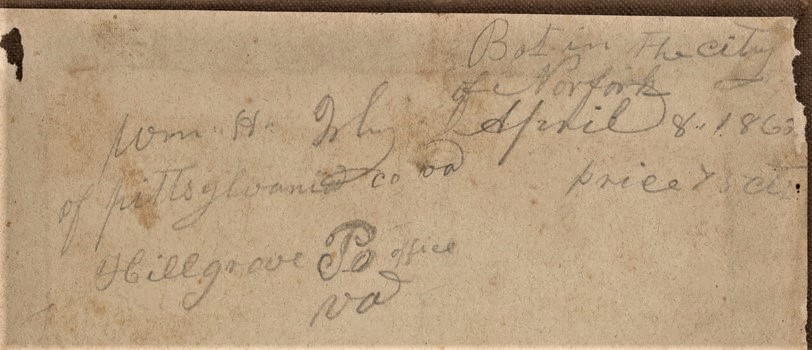

While in Norfolk, Irby had an opportunity to purchase a copy of the New Map of Virginia compiled from the latest Maps. The map is a folding pocket map with hard covers. Within the inside front cover, he wrote: “Bot in the city/ of Norfolk/ April 8, 1862/ price 75 cts./ Wm. H. Irby/ of Pittsylvania Co. Va./ Hillgrove PO office/ Va”. He would carry the map throughout his wartime service.

Shortly afterward, on April 13, 1862, Irby wrote his wife that “we went out last Thursday to Lambots Point [Lambert’s Point] to see a fight in the roads [.] The merimack [CSS Virginia] went out with several other vessels but the Yankees would not come in range of our guns [.] the merimack captured two brigs and a scooner and had them towed in by the Patrick Henry [.] they then went down near Hampton in order to draw out the yankies but seeing the merimack in the midst they took the hint and kept their distance.”

In April, the Confederate Congress passed the Act of 16 April 1862, which permitted the drafting of all white males aged 18-35 years. So, while Irby was not subject to conscription, he enlisted as a Private in Company I, 53rd Virginia Infantry in Suffolk, Virginia, on April 21, 1862, even though he was 43 years old. The 53rd Virginia remained there, training and drilling for the next several weeks.

An outbreak of measles in the camp in May led to the discharge of many members of Irby’s unit. However, Irby was discharged on orders of the Secretary of War, as he was over 35 years of age. He returned home to await further developments and tend to his family and farm.

The Confederate Congress passed an Act of 27 September 1862 that changed the conscription law. Under the act’s provisions, the President was authorized to call men 35-45 years old into service. It wasn’t until July 1863, after the battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, that the Confederacy began to call men over 40 years of age into service.

Subsequently, in August 1863, Irby was ordered to report for war service again. He reported for duty with Company G, 53rd Virginia Infantry, Barton’s Brigade, Pickett’s Division, at Camp Lee, just outside of Petersburg. When Irby rejoined, the 53rd Infantry was refitting and recuperating after suffering nearly 30% casualties at Gettysburg. Much of the fall was spent drilling and moving from camp to camp until reporting to winter quarters in Kingston, Virginia, near Roanoke.

In December 1863, Irby was hospitalized in the General Hospital in Petersburg. He would remain in the hospital until March. In a letter to Phoebe dated April 13, 1864, written soon after he rejoined his regiment, Irby writes about wanting to see his newborn daughter, Mary Catherine, as well as his wife and older daughter, Fannie. He says, “I very often dream of seeing you and the children. I suppose it is because I think so much of you & there is not money enough in the Confederacy to hier [hire] me to stay away from you as long as I have done if it was not that I feel it is my duty to abide the laws of my country and I would dislike to be considered a deserter or anything that is dishonorable I regard it more on account of my family than my self.”

After rejoining his regiment on the Chickahominy River, he participated in the defense of Richmond and Petersburg, notably at the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff in May 1864. Irby was hospitalized again shortly thereafter, first at Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, then at a hospital in Farmville, before being furloughed home. In a diary preserved in the Library of Virginia, Irby writes: “my health had become very much impaired by exposure consequently I did not get back to my command until January [1865].” His stay with his unit was short-lived, as he was in and out of the hospital for most of the spring.

In March, he was granted a certificate of disability. In his diary, he writes that “after the big fight at Five Forks, [I] was transferred to Lynchburg Hospital. Was in Lynchburg when Richmond fell […] Therefore I was not a[t] Apomatox Co. House on the 9th of April & I have always regreted not being able to be there on that occasion of Lee’s Surrender.”

On May 30, 1865, William Irby signed his parole at Campbell County Courthouse, formally ending his military service. In reviewing his service records, he was hospitalized at various times for debility, chronic rheumatism, and possibly measles. The war certainly took a toll on his health, as it did on countless veterans. However, he lived for another 35 years and brought five more children into the world. On December 29, 1900, William Henry Irby died in Danville, Virginia, and is buried in Leemont Cemetery.

In closing, I would like to thank the members of the Irby family, not only for donating the New Map of Virginia to the Museum, but also for sharing the letters, transcriptions, and photographs from the family archives with me, allowing me to tell his story.

Bibliography

Gregory, G. Howard, 53rd Virginia Infantry and 5th Battalion Virginia Infantry. Lynchburg, VA: H. E. Howard, 1999.

Irby, William H., Diary and account book, 1860-1865. Accession 31375. Personal papers collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.