The capture of Fort Pulaski on the mouth of the Savannah River had many significant implications. When the fort surrendered on April 11, 1862, it closed the port of Savannah. Accordingly, cotton exports had to be transported to Charleston or Wilmington to reach European markets. Most importantly was the impact of large rifle cannons on US coastal defense fortifications. These brick forts were considered indestructible, yet, after a 36-hour bombardment, Pulaski’s walls were breached, and it was forced to surrender. More than 40 years of military planning was changed in clouds of brick dust.

Why Savannah?

Savannah was Georgia’s largest city. Located on the Savannah River, just over 20 miles from the Atlantic Ocean, it was a leading cotton export port. Harbor activities made the town a major industrial and commercial center. The railroads that passed through Savannah northward were a primary supply link between the Deep South and Richmond, Virginia. Furthermore, Savannah featured several shipbuilding facilities and was home to the Georgia State Arsenal.

Defending Savannah

Cockspur Island, located near the mouth of the Savannah River, was initially a palisaded log blockhouse surrounded by earthworks. The fort’s purpose was to defend Savannah and enforce customs and quarantine laws. The American patriots destroyed this position in 1776. A replacement fort was constructed in 1794-1795 and named Fort Greene in honor of a Revolutionary War hero, but a heavy gale destroyed it in 1804. The Federal government abandoned Cockspur Island at that time and built a new fort, Fort James Jackson, named after a Georgia politician. Built about three miles southeast of Savannah, the fort was a second system masonry fort begun in 1808 and completed in June 1812.

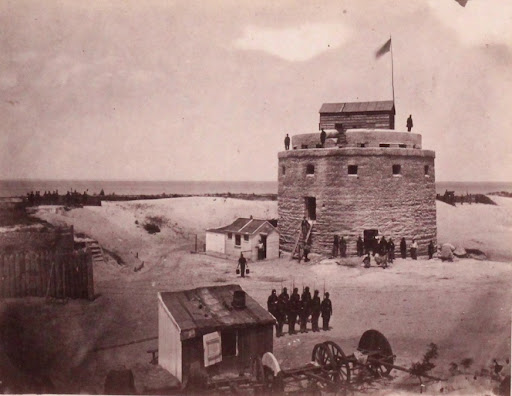

Tybee Island Martello Tower

In addition to Fort Jackson, a Martello Tower was built on Tybee Island next to Tybee Island Lighthouse. The round masonry Martello Towers became popular defensive works following the British capture during the 1794 attack on Saint Florent, Corsica. A tower defended Martello Point against naval attack, and its success prompted the British to build these towers elsewhere. The Tybee Island Martello Tower should have been about 40 feet high, armed with two cannons and walls about eight feet thick. Yet, the fort was never manned; the lighthouse keepers maintained it.

Cockspur Island Re-fortified

During the War of 1812, the United States was humiliated by its insufficient coastal defense fortifications. The young nation wished to protect its harbors better and established a Coastal Defense Board in 1816. This Board was commanded initially by Brigadier General Simon Bernard, Emperor Napoleon’s favorite aide-de-camp, and engineer. He came to America to plan the placement and designs of forts to defend the United States’ significant harbors and naval bases. Bernard and Lieutenant Colonel Joseph G. Totten (the 10th person to graduate from USMA in 1805) presented a report in 1821 detailing that national defense was dependent on: a strong navy, in-depth coastal defense, a regular army, an organized militia, and improved internal transportation. Construction had already begun on several forts when Congress approved the report. The third system of coastal fortifications followed the most modern designs to defend against the most modern cannons. Bernard wanted European-styled forts, like those built at Fort Monroe and Fort Adams. But Totten preferred smaller pentagonal forts, like Fort Sumter and Fort Macon (these were actually built in a hexagonal shape).

A New Fort on Cockspur Island

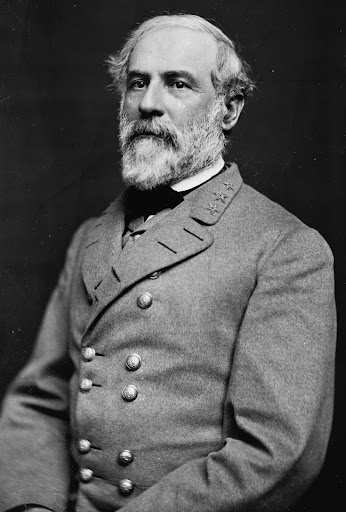

Fort Pulaski was designed by General Bernard in 1827. Construction began in 1829 under the supervision of Major Samuel Babcock of the US Army Corps of Engineers with the assistance of the recent West Point graduate (1829) 2nd Lieutenant Robert E. Lee. Lee recreated the drainage system and initiated the installation of 70-foot-long wooden pilings to support the Fort’s foundation. When Lee was transferred to Fort Monroe, he was replaced by West Point Graduate (1822) Lieutenant Joseph King Fenno Mansfield. Mansfield would remain on the project until 1846.

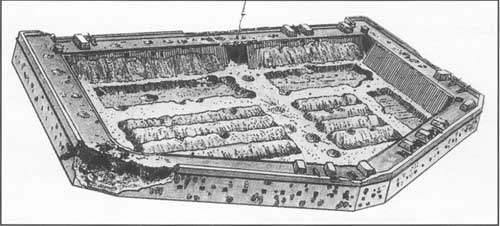

Mansfield modified the fort’s plans as the ground was too soft for a second tier of casemates. The pentagonal fort featured cannon casemate positions in a few walls and positions for guns en barbette in the terraplane. The walls consisted of 11 ½- foot- thick brick. The gorge wall accommodated the officer’s quarters, offices, etc. A demilune (ravelin) was constructed to protect the gorge and entrance to the fort. A 7-foot-deep water-filled moat, ranging from 32- to 48-feet wide, surrounded the fort. The entrance consisted of a drawbridge, a portcullis mounted in granite, and embrasures for rifles opening into the interior of the sally port. It included two half-bastions covering the gorge.

Courtesy of the National Park Service.

This massive fortification required more than 25 million bricks, made in Savannah (gray bricks). Hardened bricks required for embrasures and niches were produced in Alexandria, Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland (red bricks.) The granite came from New York. This enormous project also required vast quantities of lead, wood, iron, and other building materials. The total cost was $1 million. While the structure was completed in 1847, by 1860 only 20 of the 140 cannon emplacements were mounted with guns. Two caretakers maintained the fort for 13 years.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What’s in A Name?

The new fort on Cockspur Island was named in honor of the Polish Noble and Military Leader Count Casimer Pulaski. In 1767, Pulaski and his father joined the Bar Confederation to fight against Russian efforts to dominate Poland. Although Count Pulaski achieved several notable victories, he also endured a few significant defeats that resulted in the collapse of the Bar Confederation and the First Partition of Poland in 1772. Eventually, in 1777, Pulaski would be recommended by Benjamin Franklin and Marquis de Lafayette to General George Washington as a Cavalry Leader. Pulaski, according to Franklin, “was renowned throughout Europe for the courage and bravery in defense of the liberties of his country….” When the Polish officer arrived in America, he advised Washington, “I came here, where freedom is being defended, to serve it, and to live or die for it.”

Count Pulaski was promoted to brigadier general following his heroic service at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. It was reported that he not only saved the Continental Army from destruction but also George Washington’s life. He later organized the Pulaski Cavalry Legion and took this unit to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1779. After helping to foil the feeble attempt by the British to capture that port city, he moved his command to Savannah, where he joined the Franco-American forces besieging the city. He eventually commanded the Allied Cavalry. During the October 9, 1779, attack on the British defenses of Savannah, Pulaski was mortally wounded by grapeshot and died two days later.

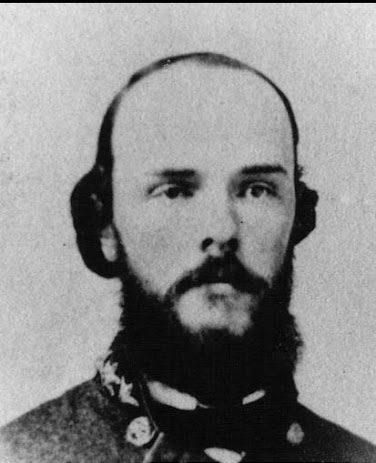

Confederate Take-Over

Georgian troops occupied Fort Pulaski on January 3, 1861. It was 16 days before that state left the Union. Eventually, Colonel Charles M. Olmstead took over command of the fort in July 1861 and manned the brick bastion with 385 officers and men of his First Volunteer Regiment of Georgia. The units within Olmstead’s command included: Company B Oglethorpe Light Infantry, the German Volunteers, the Washington Volunteers, the Macon Wise Guards, and the Montgomery Guards.

Olmstead had directed his men to make repairs and clear the mud out of the moat. They also mounted 48 guns.

En barbette:

Five 8-inch Columbiads

Four 10-inch Columbiads

One 24-pounder Blakely rifle

Two 10-inch seacoast mortars

Two 12-pounder howitzers

Casemates:

One 8-inch Columbiad

Four 32-pounder guns

Batteries outside fort:

Two 12-inch seacoast mortars

One 10-inch seacoast mortar

These were the Fort’s only guns facing Tybee Island. The remainder faced the land approach.

Defensive Preparations

General Robert E. Lee toured Fort Pulaski in late November 1861 following the Union capture of Port Royal Sound on 7 November 1862. The general had recently been appointed Commander of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Lee advised Olmstead to make defensive improvements to strengthen traverses and place sandbags between guns mounted on the parapet. He also recommended the pits should be dug on the terraplane where artillerists could take over during any bombardment. Lee directed other improvements, including cutting trenches across the parade field to trap rolling shot and laying heavy square timbers, partially covered with dirt, against the rear of the casemates to create blindages to protect Pulaski’s gun crew. Finally, he ordered Colonel Olmstead to abandon the Confederate battery on Tybee Island to focus on the defense of Fort Pulaski. “Colonel, they will make it pretty warm for you with shells,” General Lee observed, “but they cannot breech your walls at that distance.”

Pre-War Theory

Fort Pulaski was designed to withstand a bombardment using shell guns that could not penetrate Fort Pulaski’s walls beyond 700 yards. The nearest Federal battery to attack the Confederate fort was one to two-and-a-half miles away on Tybee Island. Marshes inundated Cockspur Island and nearby areas.

Brigadier General Joseph Totten, chief, US Army Corps of Engineers, insisted that the “work could not be reduced in a month’s firing with any number of guns of manageable calibers.” He added, “You might as well bombard the Rocky Mountains.”

Brigadier General Thomas West Sherman was commander of the Army Expeditionary Force that supported Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont’s capture of Port Royal Sound. Sherman, a West Point graduate of the class of 1836, had served much of his career as an artillery officer. When presented with Captain Quincey Adams Gilmore’s (West Point class of 1849) concept to capture Fort Pulaski by bombardment, Sherman replied, “All that can be done with guns is to shake the walls in a random manner.” Nevertheless, Sherman approved Gilmore’s plan.

The Union Plans Its Next Move

The capture of Port Royal Sound on November 7, 1861, provided the Union with an excellent harbor to support more joint operations along the Southern coast. Hilton Head Island was merely 15 miles away from the mouth of the Savannah River; consequently, Fort Pulaski and Savannah became an immediate target. General Thomas Sherman wanted this to be primarily a naval operation to pass by Ft. Pulaski and directly capture Savannah. DuPont demurred as he knew the various tides and unchartered shoals could trap his gunboats. Eventually, DuPont developed a serious dislike for Sherman and had the General replaced by Major General David “Black Dick” Hunter. An 1822 West Point graduate, Hunter was an ardent abolitionist.

Capture and Transformation of Tybee Island

Lawrence G. Miller, photographer.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

DuPont began to advance on November 24, 1861. The USS Flag forced the Confederates off the island. Commander Christopher Raymond Perry Rodgers led Marines and Blue Jackets to occupy the island’s lighthouse and Martello Tower. Four days later, Captain Quincy Adams Gilmore landed with elements of the 4th New Hampshire and took control of the entire island. The US Navy began supplying the troops as they started to construct siege artillery positions.

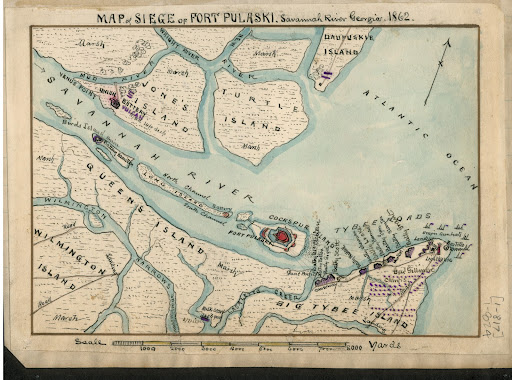

Encirclement

The Federals were able to move artillery through alligator and snake-infested marshes to create a battery to control the Savannah River. They pulled cannon through the night and established gun platforms to construct Battery Vulcan on the north side of the river. Across from Venus Point, Union troops built Battery Hamilton on Bird’s Island. The small Confederate squadron commanded by Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall endeavored to contest these Union positions, yet, the three steamers lacked the firepower to do so. By February 13, 1862, the telegraph line had been cut between Savannah and Cockspur Island. A boom was placed across Tybee Creek, which completely isolated Fort Pulaski. General Lee knew that the brick fort could not be taken by land assault or bombardment. The real threat was starvation; yet, by the end of February, the Confederates still had 16 weeks of rations remaining. With effective rationing, the supply could last until August 1862.

Robert Knox Sneden, artist.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

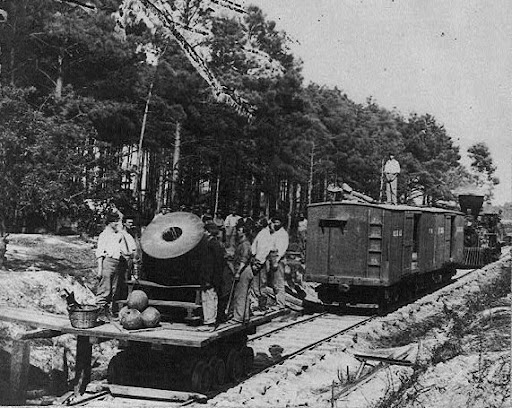

Building the Siege Batteries

By early March, Gilmore was off-loading siege materials. The siege line would reach for over two miles; consequently, corduroy roads had to be constructed. Bomb proofs and earthworks had to be built, which could only be done at night as Confederate mortars would bombard the construction effort. Before dawn, soldiers and contrabands had to cover the night’s work with reeds and brushes. Moving the heavy artillery was yet another task. The guns could only be off-loaded onto rafts at high tide and were then floated up onto the beach. A 13-inch seacoast mortar (its tube weighing 17,000 pounds) took 250 men to move it using a sling cart. Creating 11 batteries to house 36 siege guns took more than a month. These included:

Battery Totten:

Four 10-inch mortars.

1,650 yards from fort

Battery McClellan:

Two James Rifles

Two 64-pounder James rifles

1,650 yards from fort

Battery Signal:

Five 30-pounder Parrott rifles

One 48-pounder James rifle

1,670 yards from fort

Battery Scott:

Three 10-inch Columbiads

One 8-inch Columbiads

1,740 yards from fort

Battery Halleck:

Two 13-inch seacoast mortars

2,400 yards from fort

Battery Sherman:

Three 13-inch seacoast mortars

2,650 yards from fort

Battery Burnside:

One 13-inch seacoast mortar

2,750 yards from fort

Battery Lincoln:

Three 8-inch Columbiads

3,045 from fort

Battery Lyon:

Three 10-inch Columbiads

3,100 from fort

Battery Grant:

Three 13-inch seacoast mortars

3,200 from fort

Battery Stanton:

Three 13-inch seacoast mortars

3,400 from fort

Gilmore gave the four batteries closest to Fort Pulaski detailed firing instructions. Battery McClelland with four James rifles was to breach the pancoupe (blunted point of multi-faced fortifications) between the south and southwest faces. Battery Sigel was to aim its Parrott and James rifles at the barbette guns; and once they were silenced, switch to percussion shells onto the southeast wall at a rate of 10 rounds per hour. With its seacoast mortars, Battery Totten was assigned to explode shells over the northeast and southeast walls. Battery Scott was to fire solid shot and breach the same area as Battery McClellan.

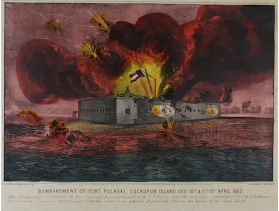

Bombardment Begins

Everything was ready by April 8; however, heavy rain delayed the action for a day. General Hunter had sent a demand for “immediate surrender and restoration of Fort Pulaski to the authority and possession of the United States.” Olmstead replied, “I am here to defend the Fort, not to surrender it.”

The following day at about 8:10 a.m., the bombardment erupted. The concentration on the fort’s southeast corner caused great damage. The efficient and accurate fire breached part of the fort’s brick walls by nightfall. The Confederates maintained good counterfire and were able to remount guns en parapet during the darkness.

The Mariners’ Museum 1939.0648.000001.

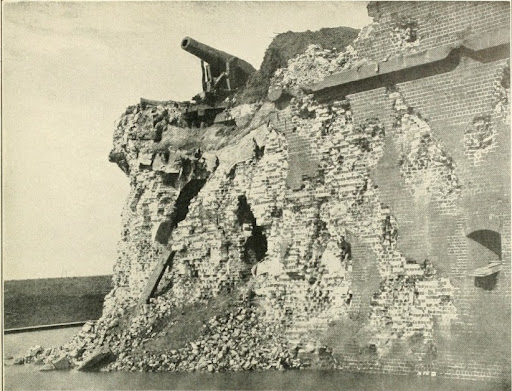

Early morning on April 11, the Federals renewed their bombardment. While the 40 guns found some targets, the rifles and columbiads opened a great gap in the wall, enabling Union shot to reach the fort’s interior. The northwest powder magazine containing 20 tons of powder was threatened. Fearing the entire fort might explode, Olmstead surrendered at 2:30 p.m.

A Tremendous Defeat

The loss of Fort Pulaski had far-reaching repercussions. The material losses hurt the Confederate war effort as they lost supplies they could not easily replace. A total of 47 cannon, 70,000 shot and shell, 40,000 pounds of gunpowder, and a three-month supply of food were surrendered. Savannah was completely closed as a blockade runners’ port. It also gave proof that the Confederate ports protected by masonry forts would need to add earthen defenses. Savannah’s defenders rushed to find new ways to protect their city. Torpedoes were placed in river channels, and floating batteries (CSS Georgia) and ironclads (CSS Savannah) were constructed to counter Union naval advances. The Confederate Army built more earthen fortifications to stop Federal threats. These efforts worked rather well, as Savannah would only be captured by land approach in December 1865.

play baseball inside Fort Pulaski.

Courtesy of the National Park Service.

Lessons Learned

In 1859, Captain Gilmore had tested a rifled cannon’s impact on fixed fortifications. During his tests, he used 32-pounder and 42-pounder seacoast guns rifled by a method developed by Major General Charles T. James. James, an industrialist and former senator, also invented a projectile for his guns. The rifling system he perfected used 15 lands and grooves.

Gilmore also used 30-pounder Parrott rifles to pound Fort Pulaski. Robert Parker Parrott, West Point class of 1820, joined the West Point Foundry Association in 1836. He devised and patented a process to forge weld spiral-coiled wrought iron cylinders over the cast iron tube. Parrott had derived the proportional thickness for the wrought iron band to surround the seat of the charge in brittle cast iron guns. The gun sizes eventually went from 10-pounder to 300-pounder rifles, and the most effective naval or siege rifle was either the 100-pounder or 150-pounder.

During the bombardment of Fort Pulaski, Gilmore recognized the range and striking power of rifles. An 84-pounder James rifle could penetrate 26-inches of brick at 1,650 yards. A 30-pounder Parrott rifle penetrated 18 inches of brick at 1,670 yards. In comparison, an 8-inch Columbiad could penetrate 11 inches of brick at 1,740 yards. Gilmore understood that against brick walls, the breaching effect of solid shot and shell was similar. Although shells did not penetrate as far, their bursting effect created a larger crater. Gilmore proved that the rifled siege artillery made brick forts obsolete; however, he simultaneously documented the ineffective fire of 13-inch seacoast mortars and did not believe that they should be used in future siege operations. Just as the battle of Hampton Roads proved the power of iron over wood, the capture of Fort Pulaski documented the effectiveness of rifled guns and the need for new types of fortifications.

Bibliography

Canfield, Eugene B. Civil War Naval Ordnance. Naval History Division, Navy Department. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1969

Gillmore, Quincy A. “Official Report of the United States Engineer Department of Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski, Georgia, February, March and April of 1862.” New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1862.

Kaufman, J.E. and Kaufman. H.W. Fortress America. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2007.

Lewis, Emanuel Raymond. Seacoast Fortifications of the United States, Washington: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1970.

Olmstead, Edwin; Stark, Wayne E.; and Tucker, Spencer C. The Big Guns: Civil War Siege, Seacoast and Naval Cannon, Alexandria Bay, New York: Museum Restoration Service, 1997.

Thomas, Dean, S. Cannons: An Introduction to Civil War Artillery. Arendtsville, PA: Thomas Publications, 1986.

Reed, Rowena. Combined Operations in the Civil War. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1970.

Ripley, Warren. Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War, New York: Promontory Press, 1970.

Roberts, Robert. Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneers and Trading Posts of the United States, New York; Macmillan Publishing Company, 1988.