In early 2019, an East Carolina University student, Jacquelyn Hewett, studied one of the figureheads in our Collection for her American Maritime Material Culture history class. The information she uncovered was enlightening and indicated that a change in the attribution of ship name was in order.1 While confirming her research, I uncovered the story of a wonderfully awesome woman I thought I would share with you!

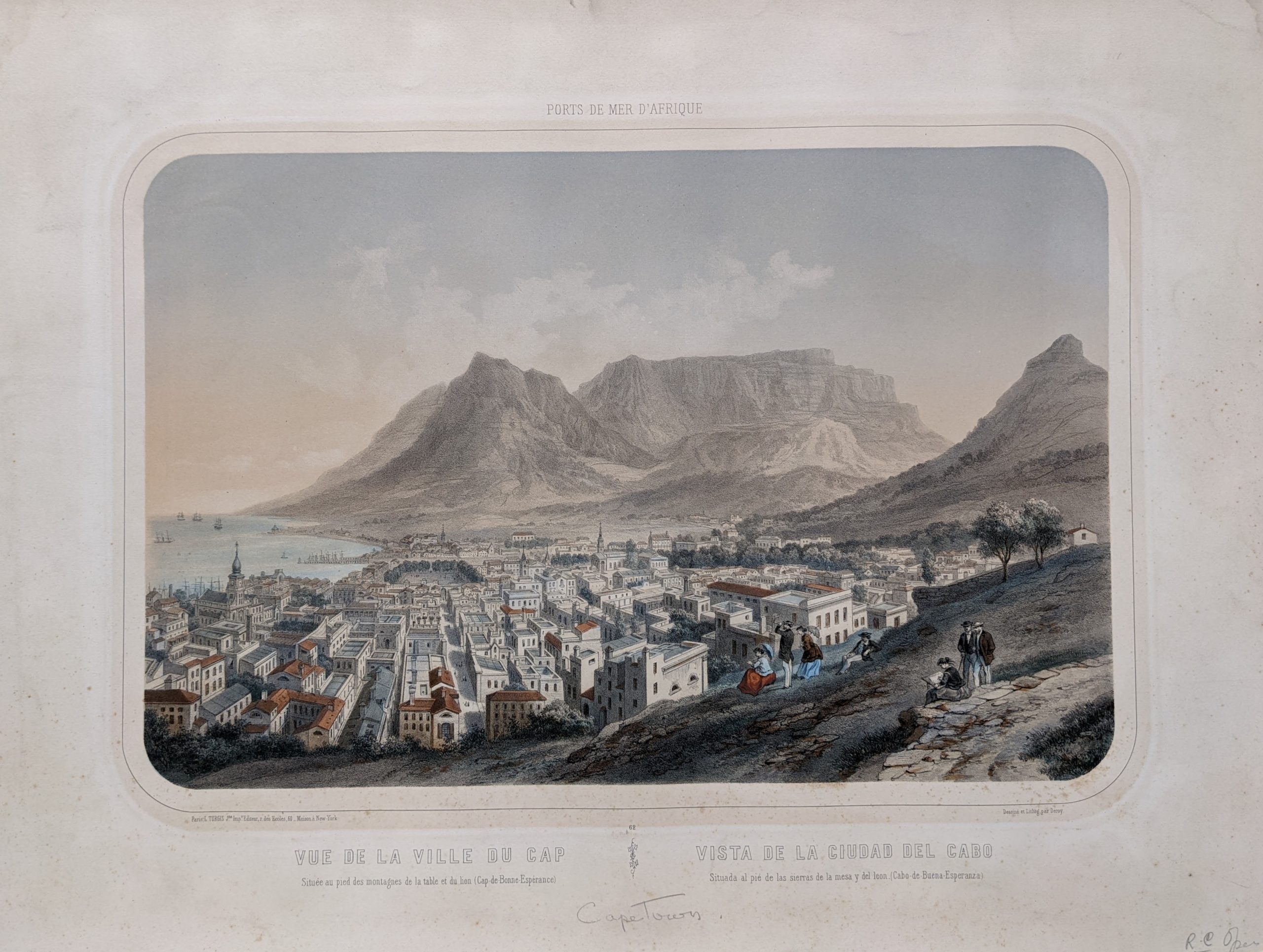

The subject of Jacquelyn’s research had been acquired in 1939 in Cape Town, South Africa, by Captain Yngve Eiserman, a marine surveyor who became a buyer for the Museum. Unlike many other figureheads in the Museum’s Collection, which are divorced from their ship history, Captain Eiserman determined the carving had come from a German-owned full-rigged ship called Galatea.

Galatea arrived in Cape Town in severely leaky condition in 1879. When a survey revealed the need for prohibitively expensive repairs, the ship was condemned. It underwent temporary repairs and became a coal hulk in Table Bay. In the early 1880s, a hurricane struck, the ship parted her cable2 ,and wrecked on Bloubergstrand beach. A man named Stevens bought the wreck, cut it up and salvaged the figurehead. The carving was later sold by Stevens’s son to Mr. Charles M. Bleach who displayed it in his hotel for many years. When Bleach retired, he placed it in the South African Museum in Cape Town for safekeeping.

Jacquelyn was able to trace the history of Galatea backward through the ship registers to the original ship – Chieftain.3 The ship had been built by Paul Curtis in East Boston for Peter Wright & Sons of Philadelphia. The ship’s construction was overseen by Thomas McGuire.4 When launched on November 15, 1864,5 McGuire became the ship’s first captain.

Between the ship’s 1864 launching and 1868, Chieftain sailed regularly between Philadelphia and Liverpool, with periodic voyages to San Francisco. In early January 1868, Chieftain left Philadelphia for Liverpool and arrived on January 30. In March, the ship left Liverpool for Calcutta and was reported there on July 23 by the New York Daily Herald. The vessel took on a cargo of linseed, jute, and gunny cloth and left Calcutta on October 28 for New York. Chieftain was reported at Sandheads on November 4, about 127 miles southeast of Calcutta in the Bay of Bengal. And here’s where the story takes an interesting turn. About four weeks after passing Sandheads, Captain McGuire was struck down with “Calcutta fever” (probably dengue fever).

When the captain’s illness struck, there were 23 crew on board Chieftain, but the second and third mates6 were comparatively inexperienced and neither had ever commanded a vessel. Without a thought to the contrary, Captain McGuire asked his wife to take command of Chieftain.

For 20 years, Mrs. Captain McGuire7 had accompanied her husband on his voyages and she had become a very knowledgeable mariner. The New York Daily Herald of March 4, 1869, stated “she knew every spar and rope and sail on the vessel. She knew every word of command. She made all the observations herself. She kept the log book. She was on deck at all hours of the day and night. She watched the barometer. She noted the shifting clouds and varying breezes.” Her strength, experience and knowledge must have been unquestioned because the crew happily obeyed her every command. Able seaman James Connolly described her as “a thorough navigator, and sufficiently skilled in seamanship to take the ship home quite as well as any of themselves.”8

While fulfilling the role of captain, Mrs. McGuire also nursed her ailing husband and mothered their eight-year-old son who was also on board. As evidence of the crew’s regard for her and her husband Mrs. McGuire said they “walked down on tiptoe and spoke only in soft whispers” whenever they were near the captain’s cabin.

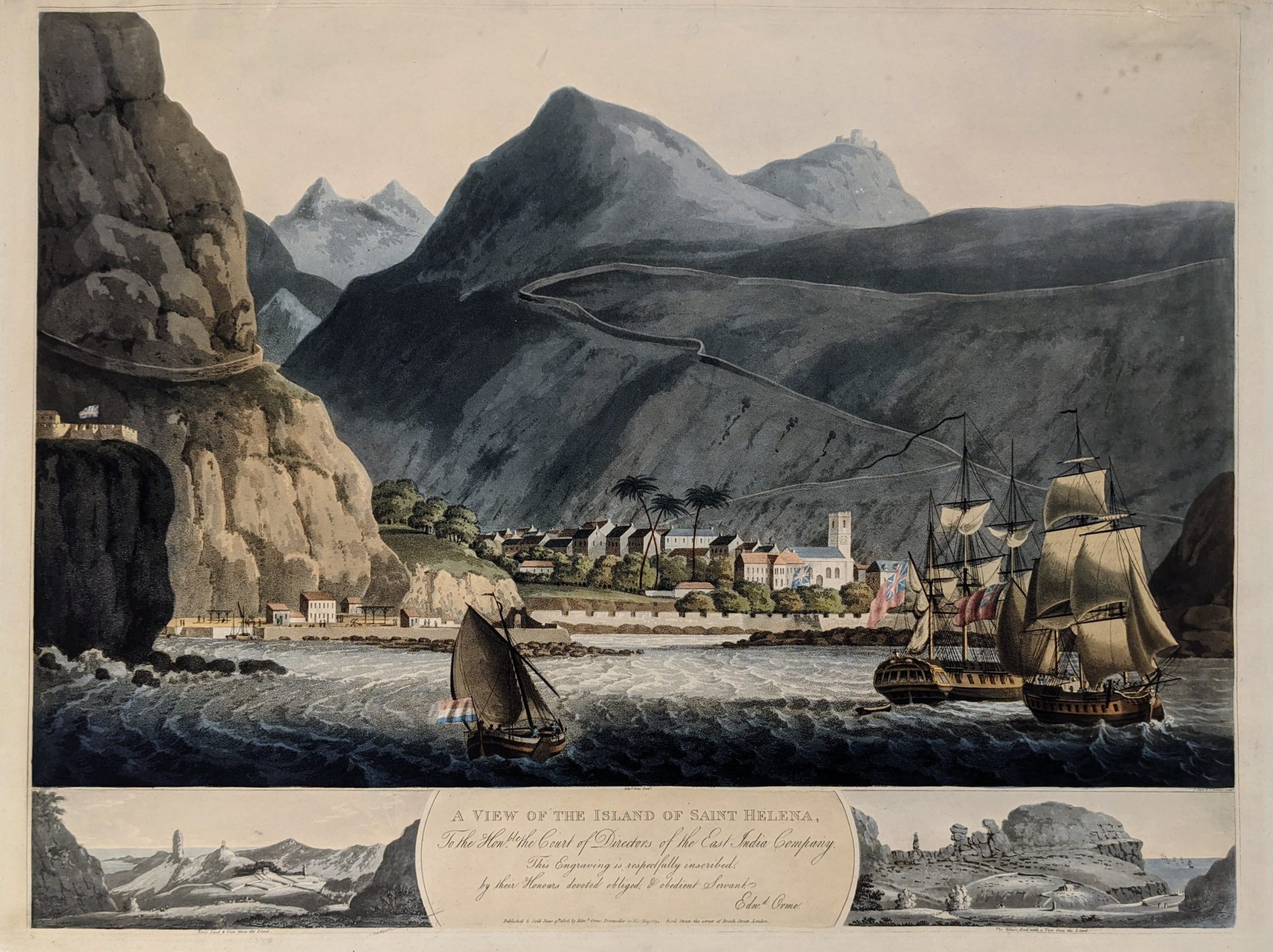

Chieftain passed the Cape of Good Hope on December 30 and arrived at St. Helena in the south Atlantic on January 10, 1869. When the merchants of Solomon, Moss, Gideon & Company learned of Captain McGuire’s severe illness they had him carried from Chieftain and lodged in a private house to provide medical care. After an examination the doctors felt that Captain McGuire would not live and the United States Consul wanted to put another captain on board. But both Captain and Mrs. Captain McGuire resolutely opposed him.

The McGuires got their way, and Chieftain continued the voyage to New York on January 15. A couple of weeks later, the ship crossed the equator and, on March 2, arrived safely in New York. Upon arrival, a great hubbub was made of Mrs. McGuire’s feat. The insurance underwriters of Chieftain presented her with a check for $1,000 for “bringing the ship safely to port.” And the ship’s consignees, Charles L. Wright & Company, said they were “highly pleased that she had retained command,” so they must have been confident in her navigation and seamanship skills.

This apparently wasn’t the first time Mrs. Captain McGuire brought a ship into port. Several years before, the entire crew of Pam Flush, including her husband, came down with yellow fever. Being the only healthy person on board, she served as captain, crew, navigator, cook, and nurse. And she still managed to get the ship safely into port!

Unfortunately, it doesn’t appear that Captain and Mrs. Captain McGuire ever went to sea again after this adventure. Extensive research also failed to uncover the remarkable Mrs. Captain McGuire’s first name. But I hope you agree that this woman was one wonderfully awesome mariner!

Footnotes:

1 We typically call the figureheads by the ship’s name unless they show an identifiable personality and we don’t know what ship they adorned.

2 This means the ship’s anchor cable broke– and there you go, you learned something new!

3 Chieftain was sold to C. Elias y Espatoso in 1870 and renamed Clothilde. Delgado & Co. purchased the ship in 1876 and named it Isabel (or Ysabel). It was then sold to H. Addicks & Company in 1877 and renamed Galatea.

4 Also seen spelled Maguire.

5 The launch date was published in the Philadelphia Inquirer on November 18, 1864.

6 The first mate was described as “off duty” by the New York Daily Herald so he may not have been on board the vessel at all.

7 None of the newspaper articles mention the wife’s name and one specifically refers to her as “Mrs. Captain McGuire.” A story discussing the incident was published in 1906 but it misnames the captain and gets so many other details wrong that I hesitate to use it as a reliable source even though the author says the wife’s name is Molly.

8 Which is interesting because in the same publication he states “our mate not having sufficient navigation to take the ship home.”