Just as the smoke cleared from the scene of the first Confederate victory at Big Bethel, onto the battlefield rapidly marched what would become one of the most colorful, daring, and poorly disciplined units of the Army of the Peninsula: Coppens’ Battalion. Also known as the 1st Louisiana or Coppens’ Zouaves, the regiment had just arrived from Richmond after a long and arduous train ride from Pensacola, Florida. The Confederate capital was “thrown into a paroxysm of excitement by the arrival of the New Orleans Zouaves…as unique and picturesque looking Frenchmen as ever delighted the oculars of Napoleon the three.” The Richmond Dispatch also noted that “their principal fare….has been crackers, cheese and whiskey.”

Drunk and Disorderly

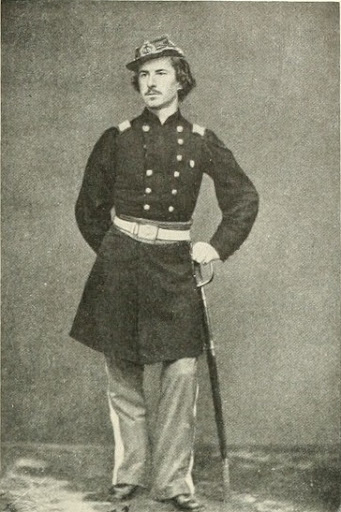

Courtesy of maritato.com

Even though they all arrived drunk, William White of the Richmond Howitzers commented, “a Louisiana regiment arrived about one hour after the fight was over. They are a fine-looking set of fellows.” But not all agreed. George Wills of the 1st North Carolina noted that the Zouaves “are the worst looking men you ever saw in your live {sic} they all had on leggings wore red pants, with about three times as much cloth in them as necessary, and a long red bag for a cap, they burnt black as mulattoes.”

On June 10, 1861, the 10-month Zouave experience in the Army of the Peninsula would begin. Several other Zouave regiments soon to arrive from Louisiana blended well with the dashing, courtly, and flamboyant leadership of the Army of the Peninsula’s commander, John Bankhead Magruder. Together they would create legends beyond comparison outside of the battlefield as Magruder’s small command endeavored to defend the Peninsula approach to Richmond.

Zouave Craze

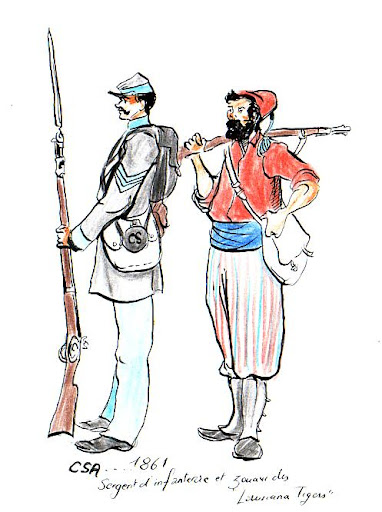

When Virginia left the Union on April 17, 1862, reinforcements were rushed to the Hampton Roads region to support Union and Confederate positions. Many of these units, like the 10th Louisiana or the 5th New York regiments, arrived at their Virginia Peninsula duty stations with great fanfare due to their unique uniforms, ėlan, and drill. The Zouave craze came to America during the late 1850s, popularized by Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth’s National Guard Cadets. Also known as the ’Zouave Cadets,’ they toured the nation in Zouave uniforms and were thrilling to watch. Ellsworth followed the light infantry drill of similar French regiments with a few dramatic additions.

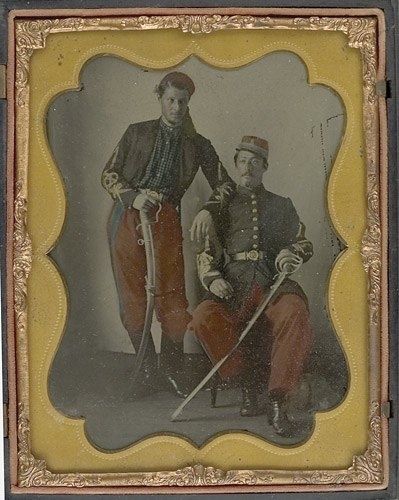

The French Imperial Army had integrated North African soldiers into its ranks during the French conquest of Algeria. These Algerian Fierce Fighters were known as “Zouaoua” and modified in French as “Zouave.” Zouaves were known as fearless warriors and colorful dressers. Soon, numerous French army units were established wearing the distinctive Zouave dress: a short collarless jacket with braid; a sleeveless vest; baggy, voluminous trousers; a 12-foot long sash; white canvas leggings; and a tasseled fez or turban wrapped around their heads for dress occasions. During the Crimean War, the Zouaves participated, earning everlasting fame from daring bayonet charges against Russian fixed fortifications defending Sebastopol. Captain George B. McClellan, an official U.S. Army observer of the siege, called Zouaves “the finest light infantry that Europe can produce…the beau-ideal of a soldier.”

Oh, to be a Zouave

When the war erupted, many soldiers sought to join Zouave regiments. In the North, numerous units formed and were overnight sensations. Colonel Abram Duryee formed the 5th New York as a highly disciplined, professional unit and enlisted only those individuals who were physically imposing and educated. Lawyers, businessmen, and the socially elite flocked to join Duryee’s Zouaves. Several very experienced officers, including West Point graduates Lieutenant Colonel Gouverneur Kemble Warren and Captain Judson Kilpatrick, were assigned leadership positions within the regiment. Duryee, a 30-year veteran of the New York militia, desired that his unit bring great glory to the state of New York.

John Butler established another New York unit following Col. Ellsworth’s concepts: the Syracuse Zouaves. Butler’s men were held to a strict moral code, and the Syracuse Journal noted, “Captain Butler…in every discipline has shown himself the model for his young comrades to copy. Courteous, magnanimous, and kind, he has attracted his associates to him by the strongest bonds of friendship and respect.” The unit left Syracuse with great fanfare. Ladies pinned Union rosettes to each soldier’s jacket. A ceremony was held where a US flag was presented to the Zouaves, and Butler thanked this assemblage with comments of appreciation: “On behalf of the company I thank you…for this distinguished token of their favor. My heart is too full for utterance, but I will testify by my acts how much I love my country. I will defend the flag to the last, and it shall be returned to you unsullied, with not a star dimmed, not a stripe diminished.” The Syracuse Zouaves were smartly clad in an exotic uniform composed of “loose trousers with white leggings, a close-fitting jacket trimmed with yellow. They also wore a dark blue cap decorated with gold lace and added a rolled red blanket that was attached to their knapsacks. The Syracuse Zouave unit was mustered in the 3rd New York regiment as Company D on May 14, 1861, and was quickly sent to Virginia.

Coppens’ Zouave Batallion

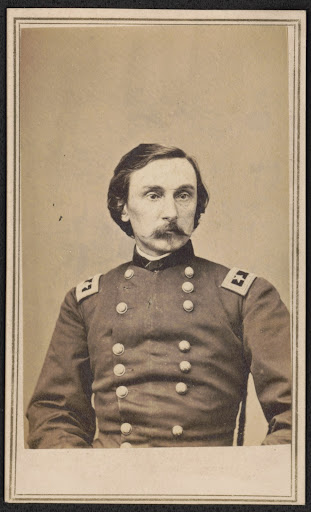

Capt. Marie Alfred Coppens, ca. March 1861.

Courtesy of CivilWarTalk.com.

The Louisiana Zouave soldiers who joined the Confederate Army of the Peninsula in June 1861 lacked the high moral and ethical codes of many of the New York Zouave units. In early 1861, a group of actors known as the Iulkennau Zouaves proclaimed to be Crimean War veterans. Traveling throughout the Gulf Coast, they were the talk of New Orleans. New Orleans socialite Gaston Coppens wished to form such a unit following Louisiana secession. Georges Auguste Gaston Coppens had arrived in New Orleans with his father, Baron Auguste de Coppens, from Dunkirk, France, by way of St. Pierre, Martinique. The French government had outlawed slavery in its colonies which prompted this move in 1854, and the family immediately became members of the New Orleans elite. Gaston had attended the French Marine Academy and was a noted duelist. Shortly after Louisiana left the Union, Gaston went to Montgomery, Alabama, to meet with President Jefferson Davis to secure a commission and permission to raise a battalion of Zouaves. Although Louisiana Governor Thomas O. Moore was displeased by Coppens’ action, a “Zouave Rendezvous” was quickly established in a 3rd Ward tobacco warehouse. The unit attracted numerous veterans of foreign wars. Many of the volunteers were recruited from New Orleans’ lawless lowlifes. The mayor of New Orleans granted Coppens permission to establish booths in the city jails, giving criminals a choice between prison and military service. Despite their backgrounds, Thomas DeLeon noted that when the battalion was finally ready to go to Virginia, they “were a splendid set of animals…sunburnt, muscular and wiry as Arabs; and a long, swingy gate told of drill and endurance….Graduates of the slums of New Orleans, their education in villainy was naturally perfect…and small disputes were usually settled by the convincing argument of a bowie knife…..Yet, they had been brought to a perfect state of drill and efficiency. All commands were given in French – the native tongue of nearly all of the officers and men, and in cases of insubordination, the former had no hesitation in a free use of a revolver.”

At right, a Louisiana Tiger (Zouave).

Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

DeLeon also noted that the Coppens’ Battalion officers “were a class entirely” above the enlisted men. They were “active, bright Frenchmen, with a frank courtesy and soldierly bearing,” Coppens had assembled an outstanding team of officers, including three members of his family such as Captain Marie Alfred Coppens of Co. F. Others like Lieutenant Jean Baptiste Souillard and Captain Fulgence de Bordeaux had served as French officers during the Crimean War. De Bordeaux could not speak English; nevertheless, several others were fluent in several languages such as executive officer Mayor Waldemar Hylsted from Switzerland who not only served as a captain in the Danish army but also fought in the American army during the Mexican War as well as in the French army during the Crimean War. Several native English- speaking officers were also important leaders within the battalion, including US Army veteran Thomas Harrison, the battalion’s quartermaster, and Ashton Miles, formerly an assistant surgeon with the US Navy. The officers were all veterans and social elites. They lived an exclusive life, according to English correspondent William Russell who witnessed the officers “seated at a very comfortable dinner, with an abundance of champagne, claret, beer and ice.”

Vivandieres

Coppens’ Zouaves even took women with them as they prepared to go to Virginia. The New Orleans Daily Delta noted that the unit “had the good taste” to bring women with them to wash, cook ,and clean their quarters; however, some thought these were “disgusting looking creatures all dressed up as men.” The Commercial Bulletin added that Coppens’ battalion’s “dress lends to the Corps a martial and picturesque appearance….The company was accompanied by two vivandieres attired in appropriate uniforms.”

When several Louisiana Zouave units – the 2nd, 5th, 10th, and 14th Louisiana Volunteers, as well as Coppens’ and Dreux’s battalions – left Pensacola by train for the battlefront of Virginia, the soldiers became “wild with whiskey.” Many sat atop the cars “making ring with the wild yells and the roaring chorus of the song of the Zou-Zous.” When train stops occurred, several communities were raided for whiskey and everything else that could be taken. The frenzy of these drunken men caused every form of excess and retaliation from their officers.

Drunken Devils

The 14th Louisiana, commanded by Colonel Valery Sulakowski, was also known as the ‘Polish Regiment.’ Its soldiers came from throughout Europe. Sulakowski, a Polish noble, had immigrated to the United States after the failed 1848 Hungarian Revolution. A strict disciplinarian, he was one of few who could control the wild soldiers who typified the Louisiana Zouaves. Entrained to Virginia, Sulakowski had to shoot several of his raucous, drunken men during a stop-over in Grand Junction, Tennessee. When the Zouaves arrived in Richmond, Sallie Putnam defined them as “a calamity….Whenever a Zouave was seen, something was sure to be missing…The whole community…drew a long breath of relief when they left.”

When the Louisiana units arrived on the Peninsula, they continued their wildness and disregard for military order. Brigadier General Lafayette McLaws noted that the Louisiana Zouaves units had the “reputation of being the most lawless in existence.” McLaws added that the 10th Louisiana was “on Jamestown Island for twelve hours & during that time, tis said, eat up everything on the island, but the horses, and their own species.” He also told his wife a story that “the Zouave who had been watching a pig for some time, waiting for him to come into his vicinity, lying flat on the ground for the double purpose of concealing himself from the pig & from general observation, when a North Carolinian coming along boldly shot the pig. The Zouave immediately rose up on his hands and shouted out, ‘Ah de Zouave is not the only one shoots de pig, somebody else is the d__d rascal besides.’” A few found justification in their foraging, as Benjamin Smith of the 5th Louisiana wrote, “I loaded my musket once or twice with the expectation of hurting someone…As for my bayonet it had only been stained by the blood of an unfortunate pig, who was foolish enough to tempt a hungry soldier. I devoutly hope that, he was a Yankee pig.”

The Coppens’ Zouaves were especially disruptive and destructive. It was noted the “pirates are from the dregs of all nations and during the ten days they were here (Mulberry Island), they killed some eighteen or twenty head of cattle.” Finally, General Magruder had to take measures to suppress the problem. Magruder approached Coppens’ Battalion during a June inspection with a severe reprimand. An onlooker described the scene, noting that the “Zouaves sweated profusely while their commanding officer chided them for the rash of cattle killings. Magruder informed the Zouaves that he had heard of their deprecations and that they must be stopped, or every man who was guilty of such conduct…would be shot immediately.”

‘The God of Battles’

Despite the uproar often caused by the Zouaves, there was constant skirmishing between the Union and Confederate forces on the Peninsula in the ‘no man’s land’ between the southwest (Newmarket Creek) and the northwest branch (Brick Kiln Creek) branches of the Back River. On July 3, 1861, Magruder ordered Lieutenant Colonel Charles D. Dreux to take the 5th Louisiana with elements of a local unit, Wythe Rifles, and artillery to set an ambush for Federal foragers. The Louisianans erred when a Zouave shot a rattlesnake just as Dreux stepped out of the woods to spring the trap. He was immediately shot and killed. Dreux was the first Louisianian and Confederate field-grade officer killed during the war. “Colonel Drue’s [sic] death was mourned by those who knew him–on account of his bravery and high military genius, remembered Lieutenant William J. Stores. Dreux had just written a letter to his wife with a premonition of his death: “The boys are delighted with the prospects before them, and we are all in the highest glee. May the God of Battles smile upon us. Cheer up dear wife. I have the brave hearts and strong arms to sustain and cheer me on, and I feel confident of the result. Many a noble son may fall by my side, and I may be the first to bite the dust, but rest assured that they or I will always be worthy of the esteem and respect of our country men ….”

Despite the alerts and brief skirmishes, the Army of the Peninsula Zouaves often complained that their lives were “Dull, dull, dull,” as William Monroe of Dreux’s Battalion expressed. Leon Jasterminski of the 10th Louisiana recalled a typical day: “Reveille at 5 o’clock a.m. Roll call. Then we cook our breakfast….Half past eight, guard mounting, which is equal to a small parade…At 9 o’clock company drill until 10 o’clock after which we are free until 12 o’clock when we have dinner call, which comes what is called fatigue duty which means spades….After which we are again free until 6 o’clock. Then dress parade & dismiss [to] cook our supper, eat, loaf, & spin yarns until 9 o’clock when Tattoo beats & we are all sent to bed like a parcel of school boys…This occurring every day makes it very tiresome.”

The soldiers generally were well fed as Magruder developed an excellent food supply system, Zouaves enjoyed the land of plenty, and oyster-eating contests were extremely popular. A friendly competition occurred in the 10th Louisiana to prove whether or not the Warwick River bivalve was more succulent than those from the York River. Another wrote home, “I am living and growing fat on oysters and soft shell crabs.” All was not perfect, though, as many soldiers complained of nights when “musketeers [mosquitoes] swarmed around in myriads.” Sickness was commonplace among the Zouaves unused to the “swelter and pestilential marshes of the Peninsula.” About half of Dreux’s Battalion was taken ill in August 1861, and in September, only 100 men of Coppens’ Battalion were fit for duty. Camp fever became so commonplace that one young Zouave wrote to his parents, “the death of one of poor soldiers is hardly noticed….it seems to me that it was noticed no more than if a dog had died.”

Early in September, General Magruder removed Company F, commanded by Captain Paul De Gournay, from the battalion to help construct water batteries at Yorktown. Eventually, the unit would be reorganized as the New Orleans Heavy Artillery. Coppens’ battalion and several other Zouave units were transferred to Williamsburg, away from the fever-producing marshes of the Lower Peninsula. While in the old Virginia colonial capital, several companies were given flags from the town’s ladies. The color sergeant of the DeSoto Rifles received the unit flag during a ceremony and remarked, “Ladies, with high beating hearts and pulses throbbing emotions, we receive from your hands this beautiful flag, one proud emblem of our young republic….To those who may return from the field of battle bearing the flag in triumph, though perhaps scattered and torn, this incident will always prove a cheering recollection.”

Master of Ruses and Strategy

Regardless of sickness or any other malady, the various Louisiana Zouave units enjoyed their service under the dramatic leadership of Major General John Bankhead Magruder, nicknamed ‘Prince John’ for his flamboyant dress and cosmopolitan lifestyle. While there were rumors of Magruder’s drinking, the general had pledged to Jefferson Davis that he would not use any “intoxicating liquors of any sort for the war’s duration.” During a ball sponsored by Colonel Valery Sulakowski of the 14th Louisiana, “the great Paragon of Virtue and Sobriety Gen. Magruder was so drunk that he fell from the arm of the whore he was dancing with and would have burned to death had he not been pulled from the fire by one of his orderlies.” During the 1862 Mardi Gras season, members of Dreux’s Battalion played a prank on Magruder during the celebrations in Williamsburg. Baby-faced Billy Campbell dressed as a woman and strode into the ball on the arm of Ned Phelps who was introduced as an unmarried sister of one of his fellow soldiers. “The gallant Magruder quickly took the ‘lady’s’ hand and began entertaining Campbell with food, drink, and lively conversation.”

Meanwhile, several other battalion members went to a bedroom above Magruder and, using a mattress, pushed feathers through the cracks in the floorboards. Magruder was covered with feathers as the men all shouted that it was a ‘Louisiana snowstorm.” Campbell and Phelps slipped away, leaving the general somewhat confused.

‘Rakish and Devilish Looking’

Magruder’s Peninsula defenses would soon be challenged by Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. On April 4, 1862, McClellan began his march up the Peninsula toward Richmond. The next day, McClellan’s command progress was stopped by the 13,000-strong Army of the Peninsula’s Warwick-Yorktown network of fortifications. Magruder bluffed McClellan into believing the Confederate force was much larger by marching his men up and down the earthworks. McClellan laid siege to the Confederate defensive system and began building gun emplacements for the 102 heavy guns he had brought with him. The Confederates, now numbering over 56,000 men and commanded by General Joseph E. Johnson, slipped out of their defense during the evening of May 3, 1862. McClellan organized a pursuit which resulted in the May 5, 1862, battle of Williamsburg. Coppens’ Zouaves were assigned to defend Redoubt 6, also known as Fort Magruder, which was the center of the Williamsburg Line built by Prince John Magruder. The battalion was not heavily engaged and joined the rest of the Confederate army’s retreat that evening. As the Zouaves marched out of Williamsburg en route to Richmond, they passed several captured wounded Union soldiers who had been laid out along the roadside. One young Federal soldier, shot through the abdomen, pleaded to be killed to stop his suffering. A Zouave dropped out of line to join a group gathered around the wounded man. He asked him, according to Robert Stiles, “Put you out of your misery? Certainly, sir!” and then smashed the Federal’s head with a shot from his musket. The Confederates surrounding the scene backed away from the horrific act by this “demon.” Untroubled, the Zouave asked the other wounded men, “Any other gentlemen here like to be accommodated?” No one replied, so the Zouave returned to his place in line. Stiles watched as the Zouaves marched away, saying that Coppens’ Battalion “were the most rakish and devilish looking being I ever saw.”

The Louisiana Zouave units which served on the Peninsula shocked all with their unruly, cutthroat, and drunken behavior. Nevertheless, many viewed them as some of the most daring and dangerous units serving in Magruder’s army. The mystical look of their uniforms and their French-spoken commands made them appear as giants among men and fitting companions to their dashing commander, Major General John Bankhead Magruder.

Sources

John V. Quarstein, Big Bethel: The First Battle, Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011.

John V. Quarstein and J. Michael Moore, Yorktown’s Civil War Siege, Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012.