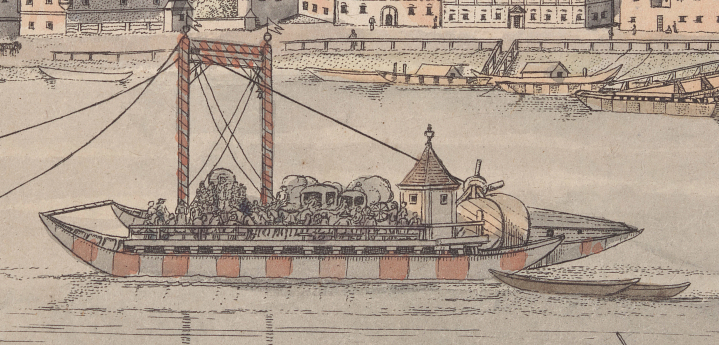

Recently, I was looking at engravings of the terrible European floods of 1783-1784, and I stumbled across an image of a very confusing watercraft. The vessel appears in a view of Pressburg, Hungary (now Bratislava, Slovakia). The image shows the city in 1787 from across the Danube River. The strange watercraft is a double-hulled pontoon with a large framework mounted on its deck. It’s shown sitting in the middle of the river with a long line of smaller boats attached to one end. At first, I wondered if the vessel was being towed or if it was doing the towing. But then I noticed the wooden landings on each riverbank and realized it must be some sort of ferry.

The scene immediately raised several questions, the first being, “How in the heck does this boat work?” which was quickly followed by, “Why not just build a bridge?” I also wondered if we had other images in our Collection that show what seemed to be an odd type of ferry. Luckily, I was able to answer all these questions, learning some very interesting history in the process!

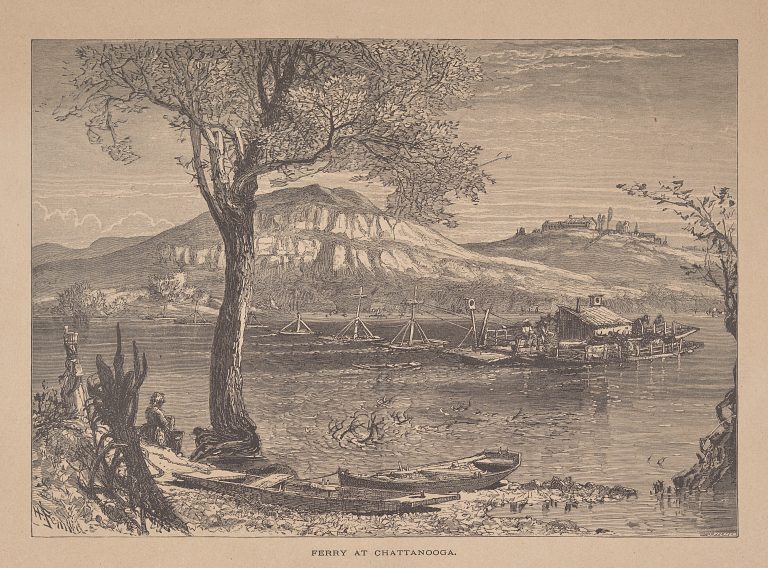

Historically, this unique craft is called a “flying bridge” or “yaw ferry.” The first flying bridge was installed in the Netherlands in 1657, and they’ve been used to cross rivers all over the world ever since (I found a flying bridge on the Tennessee River at Chattanooga in 1872!). The flying bridges in use today seem to be a slightly modified form, mainly used to transport tourists. Their method of propulsion remains the same – they are propelled solely by the strength of the river’s current and nothing else. These days they’re commonly called “reaction ferries.”

So, how do “flying bridges” work?

First, you need a specific kind of river. It can’t be slow flowing or overly wide. If you have a fast or strong-flowing, fairly narrow river that needs crossing, a flying bridge may be the perfect solution.

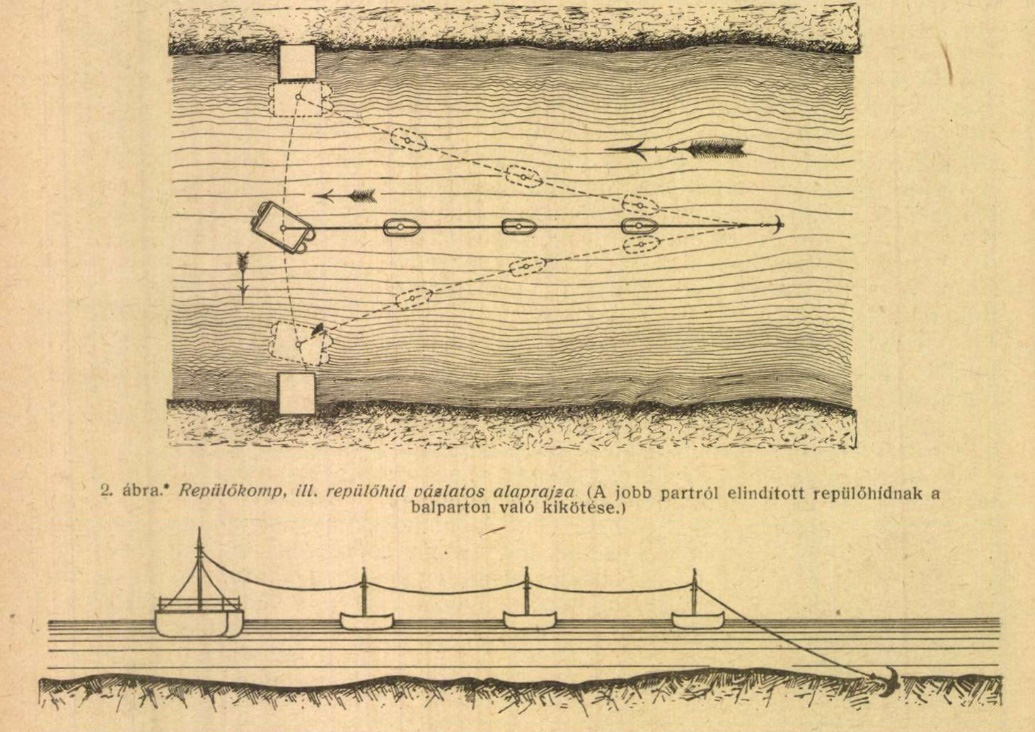

To set up a flying bridge, a strong anchor (or piling) is sunk in the middle of the river upstream at a distance two to three times the width of the river away from the site of your chosen ferry landing. A thick, strong rope stretches between the anchor and the ferry platform downriver. The rope is raised above the water on a series of forked posts installed on flat-bottomed boats. This is very important; if the rope is left dragging through the water, it creates so much friction the ferry would stop moving forward around the middle of the river. Not to mention that leaving the rope underwater increases the probability it will snag on some underwater obstacle. Raising the rope tether above the water lets the ferry platform swing like a pendulum from one side of the river to the other.

The construction of the ferry platform is also essential. A flying bridge typically has two hulls with a large wooden platform stretched between them. Using a catamaran-like hull provides two benefits. First, it increases the boat’s width, which makes the ferry more stable. Second, having two hulls increases the surface area that comes into contact with the water. Increased hull surface area touching the water equals greater thrust.

Near the bow of the ferry platform is the vessel’s steering mechanism consisting of a 15’ -18’ tall wooden framework with two parallel beams at the top. Between the two beams is a sliding metal fitting or roller. The ferry’s rope tether is passed through the fitting and secured around a winch at the vessel’s stern. To launch the ferry, the bow is angled toward the opposite bank of the river (the direction you want to go), which causes the metal fitting holding the tether to slide toward the bank the ferry is leaving (check out the image below). The placement of the rope tether on the opposite side of the ferry from its direction of travel lets the vessel maintain its angle across the river’s current and travel all the way across the river. If the tether were positioned in the middle of the vessel and didn’t move, the ferry would stop moving forward when it reached the middle of the river.

The ferry is fitted with one or two rudders to angle the vessel and maintain the tether’s position. The ferry may also be equipped with several leeboards. The leeboards can be raised or lowered according to the vessel’s travel direction to help increase the ferry’s resistance against the current and the vessel’s thrust. Speed is regulated by increasing or decreasing the angle of the hulls in relation to the current’s direction. The winch at the stern around which the rope tether is secured is used to change the length of the tether to accommodate changes in the river’s water level.

So why install a flying bridge instead of something more permanent?

I would imagine that in some instances, the reason permanent bridges aren’t installed is one of economics, and there isn’t enough traffic to justify the expense. In the case of the Danube, warfare and ice were the biggest impediments to the construction of a permanent river crossing.

In the 16th century, floating bridges like the one pictured below crossed the Danube in several places. Most, if not all, were destroyed during the Ottoman takeover of much of Hungary in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the case of Pressburg, which sat between the Turkish armies and Vienna, the city they were trying to seize, the town’s inhabitants intentionally dismantled their floating bridge to protect themselves from an Ottoman invasion.

By the late 17th century, the invasion threat was lessening, and the need for a river crossing into Hungary’s new capital city was great (the capital had moved there after Buda was captured by the Turkish). In 1676, the city installed a flying bridge because of the continued threat of warfare and the even greater threat posed by river icing over in winter. The flying bridge was easily removable if the Turkish showed up or at the first appearance of winter ice. The flying bridge could easily be reinstalled when the Danube became ice-free in the spring.

Flying bridges were highly successful and were installed at several locations besides Pressburg. One ran between Buda and Pest2, and another connected Esztergom (Hungary) with Párkány (Štúrovo, Slovakia).

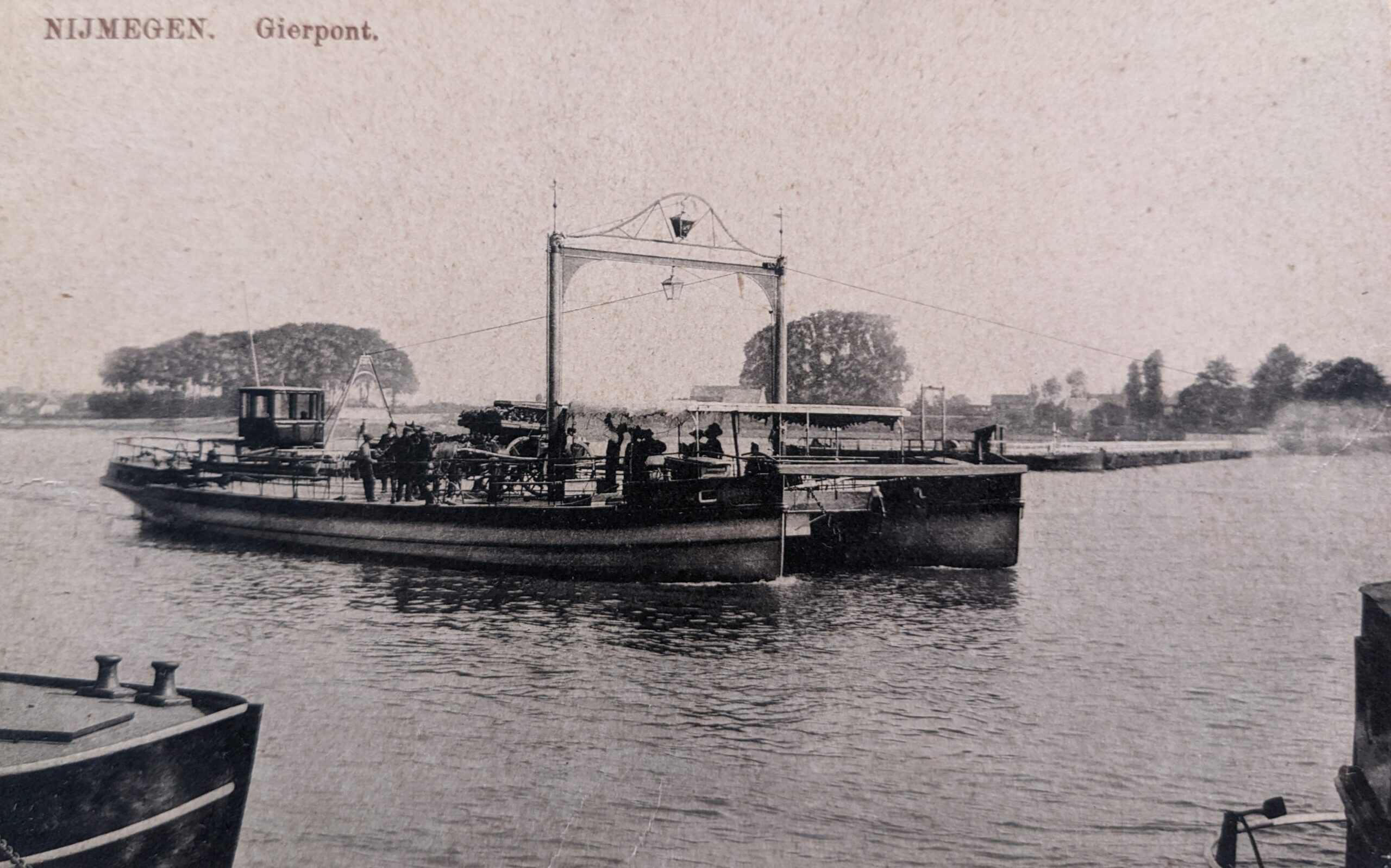

As mentioned earlier, flying bridges are a cost-effective way of installing a river crossing, especially if your volume of traffic isn’t overwhelming. The ferry at Nijmegen on the river Waal in the Netherlands was first installed in 1657; it remained operational for centuries. This flying bridge was decommissioned in 1936 when the permanent Waal Bridge (also called the Road Bridge) was built. On May 10, 1940, during the German invasion of the Netherlands, Dutch military engineers destroyed the bridge to slow the German advance. The bridge wasn’t repaired and reopened until 1943.

So how did they cross the river in the meantime? They recommissioned the flying bridge!

Endnotes

- I found this image/article referenced in two sources. The first is on page 137 of the article “A Pest-Budai Repülőhíd” by Morvay Endre in the publication Tanulmányok Budapest Múltjából, XIX. The second source is a blog post by Csaba Domokos titled “255 éve szűnt meg a repülőhíd Pest és Buda között – A folyó sodrása működtette a különleges kompot” on the website Pestbuda.hu. Unfortunately, I was unable to find a copy of the original article by Lósy-Schmidt.

- Buda was the historical capital of Hungary and sat on the western bank of the Danube River. Pest was a town directly across from Buda on the eastern bank of the Danube. On November 17, 1873, Pest and Buda were united with another town, Óbuda, to form the modern Hungarian capital of Budapest.