SCENE 1:

WANTED! Men and women willing to travel to the beautiful tropical colony of Kourou in the Americas. All material needs supplied. All expenses paid.

SCENE 2:

Eight months later…

It’s hard not to laugh when you think about Monty Python, but the reality of France’s 18th-century colonization efforts is truly horrifying. It was one of the world’s greatest government-caused humanitarian disasters, and it’s a story that should be shared, remembered, learned from, and never be repeated in any way.

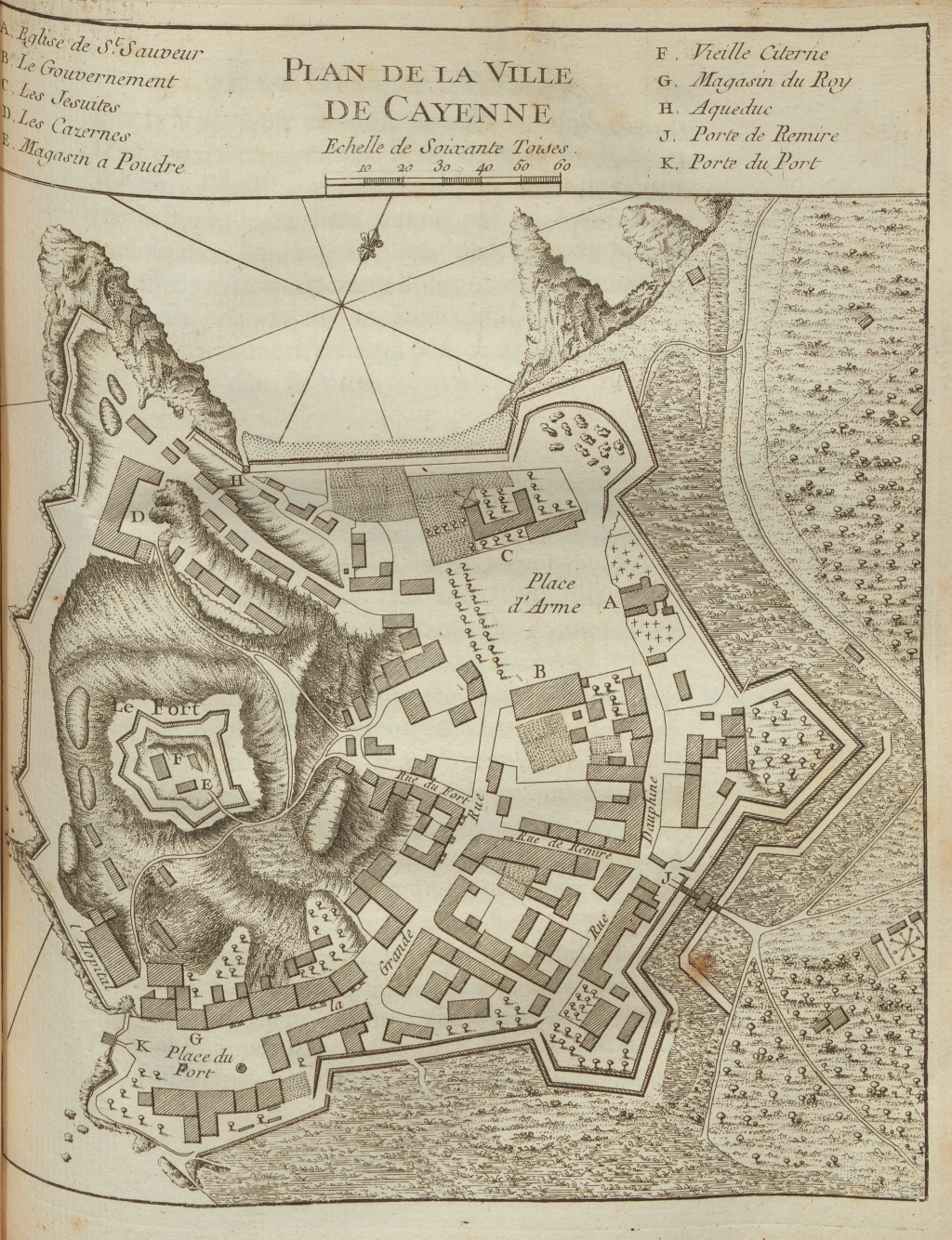

It all started at the end of the Seven Years’ War. The Treaty of Paris forced France to cede its colonies in Canada, Grenada, Dominica, and Tobago to Great Britain. The small settlement of Cayenne in Guyana (now French Guiana), called France Équinoxiale1 at the time, was the country’s only remaining colony on the American continent2. Bounded by the Maroni River in the north and the Oyapok River in the south, Cayenne was a small, impoverished colony of about 575 settlers and almost 7,000 enslaved people.

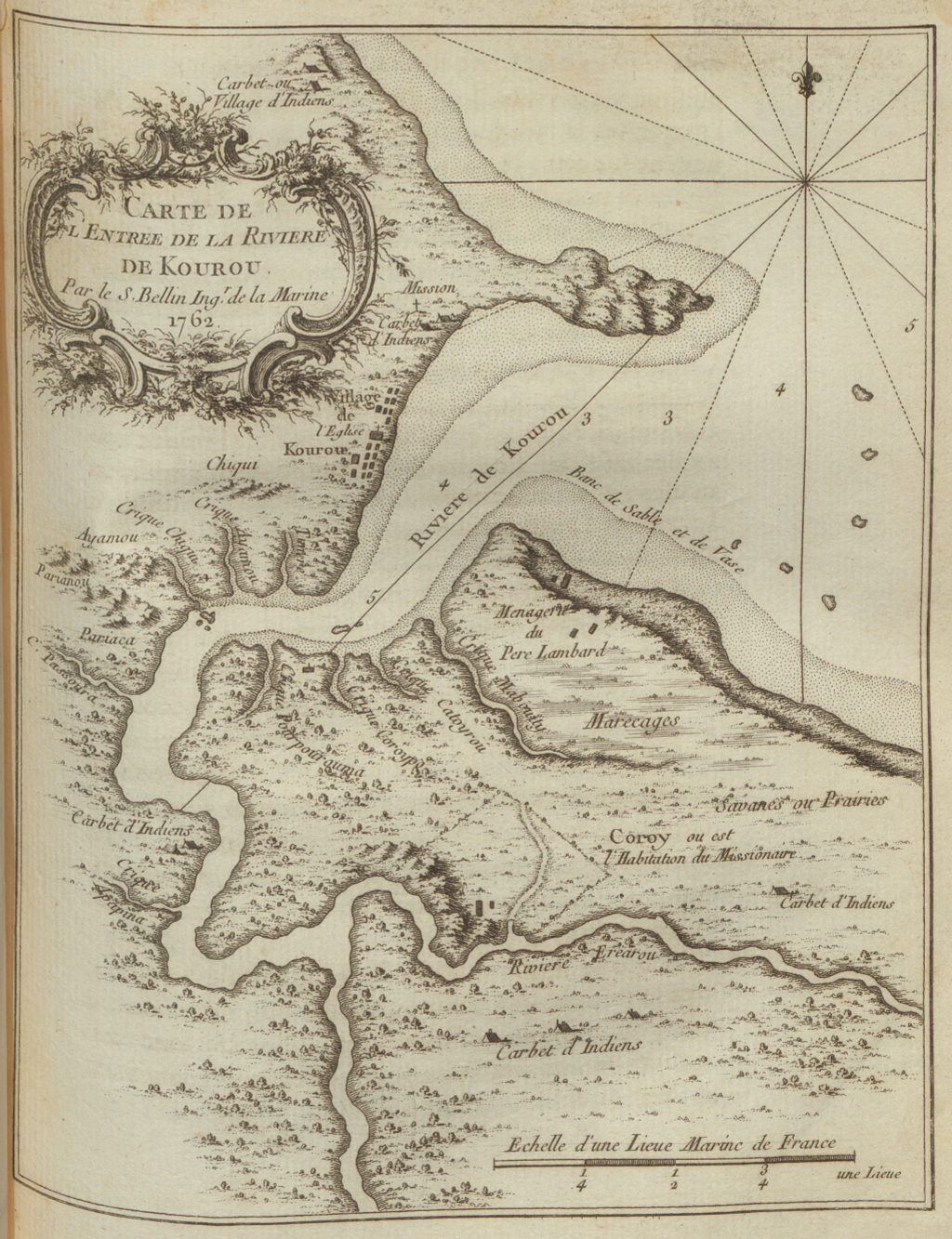

Having lost its largest and richest colony, France was determined to expand its small foothold on the South American continent. If successful, at some point in the future, it could be used as a base of operations for launching attacks against British possessions in North America and the West Indies. In 1762, France’s minister of the navy and colonies, the Duc de Choiseul, began organizing a massive colonizing expedition to Cayenne and Kourou, a river about 37 miles northwest of Cayenne. Kourou was chosen because it was believed to be a lush area full of beautiful plants and abundant gold3.

The Duc de Choiseul’s administration recruited settlers from all over France and parts of Europe, especially Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland. Even the island of Malta was targeted as a source of settlers. Choiseul promised that anyone traveling to Rochefort, the port of embarkation for the expedition, would have their travel costs and subsistence covered, and their transportation to Guyana would also be free.4 Once in Guyana, the colony’s organizers and King Louis XV promised to fully support the settlers for two-and-a-half years. They would be given plots of land; housing; food, including all the vegetables they were familiar with in Europe, cattle (they even transported 14 water buffalo and their handlers from Civitavecchia, Italy!), and all species of poultry; as well as clothing.

The king himself ordained that the colony would be a land of enlightenment. A place with all the advantages of the British American colonies – only better. The importation of enslaved Black people was expressly prohibited except in the direst circumstances, and the native Indians would be protected. They even encouraged marriages between the settlers and native women. Settlers were promised a society with freedom of conscience with no imposition from the government, freedom of religion, and freedom of maritime commerce; the settlers would pay no taxes. Additionally, any settlers who managed to give birth to a son would receive a reward.

Worried the colonists would become depressed, feeling trapped so far from their home countries, the organizers recruited a troupe of clowns and musicians to entertain the new colony. There were tambourine players, several horn players, a violinist, a guitar player and composer, and nine German musicians (I’m not sure what instruments they played). They even recruited an 8-year-old harpist from Koblenz. Also recruited were botanists, naturalists, doctors, agricultural workers, merchants, artisans, and the “most virtuous and the most understanding men to be governors and intendants”5 of the settlement. The one thing the government neglected to supply was enough food.

Convinced by all the extravagant and too-good-to-be-true promises, nearly 17,000 men, women, and children, mainly from Alsace and the Rhineland, streamed across France to take the French government up on its offer. A naval administrator named Victor Pierre Malouet was tasked with reviewing the new settlers. He was shocked by what he saw, calling it a “deplorable spectacle.” He stated the new colonists were “imbeciles of all kinds” mixed with farmers, merchants, nobles, artisans, city folk, gentlemen, civil and military servants, and a troupe of clowns and musicians.6 Another source called the settlers “the scum of the population of the east of France.”7

While the settlers living in Cayenne before this expansion attempt did manage to support themselves, mainly with the help of enslaved persons and native Indians who hunted and fished, they certainly didn’t produce enough to support the thousands of new settlers, no matter how many supplies were sent from France. Cayenne’s governor and the colony’s leading planters thought it was sheer madness to send so many unacclimatized Europeans to Guyana and expect them to start plantations without the help of enslaved people. Most likely trying to save themselves, they refused to help or support the new settlers in any way.

The first group of Kourou settlers managed to clear a small plot of land (with the help of enslaved people loaned by a nearby Jesuit mission) and started building 14 rows of leaf-covered huts. But before the shelters could be completed, 300 more settlers arrived, quickly followed by more than 1,400 others. The settlement’s leadership tried to stop the flood of immigrants, but their efforts failed. In the spring of 1764, another 1,400 settlers arrived and were sent to the Isles du Salut, a small group of islands off the mouth of the Kourou River. Before you get excited by thinking, “the Salvation Islands, well, that can’t be too bad!” believe me, no salvation was involved. The island group’s original name was the Isles du Diable (the Devil’s Isles), but the name was changed so it wouldn’t terrify the people sent there. Within months they had packed 1,300 more people onto the islands. At one point, so many tents covered the islands that a passing British merchant ship thought the tents housed an invasion army.

In the end, somewhere between 13,000 and 15,000 people were sent to Kourou. Packed together into such tight quarters under terrible living conditions, most settlers succumbed to epidemic diseases (most likely typhoid fever), starvation, or simply from pure despair within a few months of their arrival. The medical officer on site in the fall of 1764 was trying to treat 1,400 to 1,500 sick people every day. They died so fast, and in such numbers they couldn’t even be counted.

Surgeon Bertrand Bajon described the colony as one of “sorrow, indolence, foulness, filth and despair.”8 When Étienne François Turgot, the governor of Guyana arrived in December 1764, nineteen months after the first settlers arrived, he wrote, “I could not restrain my tears…I saw myself surrounded by a multitude of emaciated and pale widows and orphans of both sexes bathed in tears, who clasped their hands and raised their eyes towards heaven.”9 Turgot and his entire household became sick almost immediately, and 12 of its 20 members died. The new governor was nearly blinded.

By April 1765, Turgot had abandoned the colony with about 919 survivors. Over the few years of the colonization attempt, about 3,000 survivors managed to return to France, but they continued to die from the diseases they brought back. They also launched epidemics in the ports to which they returned. Despite the masses of people delivered to Guyana, by 1770, the population had only grown to about 1,178 people.

After the colonization of French Guiana failed, “French colonial interest turned to buying slaves to fill the colony.” And while France retained control of Guyana and some islands off the coast (it would lose St. Domingue in Toussaint L’Ouverture’s rebellion of 1791-1803), the Kourou collapse essentially ended France’s ambitions as a continental power in the Americas.

ENDNOTES:

1. The Latin word Équinoxiale means “of equal nights.” It refers to French Guiana’s location on the equator, where the days and nights are of equal length.

2. For those of you thinking, “What about New Orleans?” like I was, in 1762, France had ceded Louisiana (everything west of the Mississippi, including New Orleans) to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau, so as far as France was concerned, New Orleans was no longer a French colony.

3. The Guyana region was once thought to be the location of the mythical city El Dorado.

4. One gets the impression from Emma Rothschild’s paper “A Horrible Tragedy in the Atlantic” that the promise of reimbursing travel costs was probably not fulfilled. See page 76 for the story of a newspaper that reported a German servant girl begging for help after her family, now destitute, had walked from Alsace to Paris. The editor of the paper was promptly arrested for reporting on the situation, probably to prevent word from getting out that the grandiose promises being made by the French government were not being kept.

5. November 27, 1763, letter from the Duc de Choiseul to Voltaire.

6. Victor Pierre Malouet, Collection des Memoires et correspondances officielles sur l’administration des colonies, et notamment sur la Guiane française et hollandaise, Paris, 1802.

7. From Précis historique de l’Expedition du Kourou, pages 47-48.

8. M. Bajon, Memoires pour servir a l’histoire de Cayenne, et de la Guiane françoise, (Paris, 1777), volume 1, page 61.

9. December 24, 1764, letter from Étienne François Turgot to the Duc de Choiseul.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“A Horrible Tragedy in the French Atlantic” by Emma Rothschild, published in Past & Present, August 2006, No. 192, pp. 67-108.

“Colonial Experiments in French Guiana, 1760-1800” by David Lowenthal, published in The Hispanic American Historical Review, February 1952, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 22-33 relate specifically to the attempt to colonize Kourou.