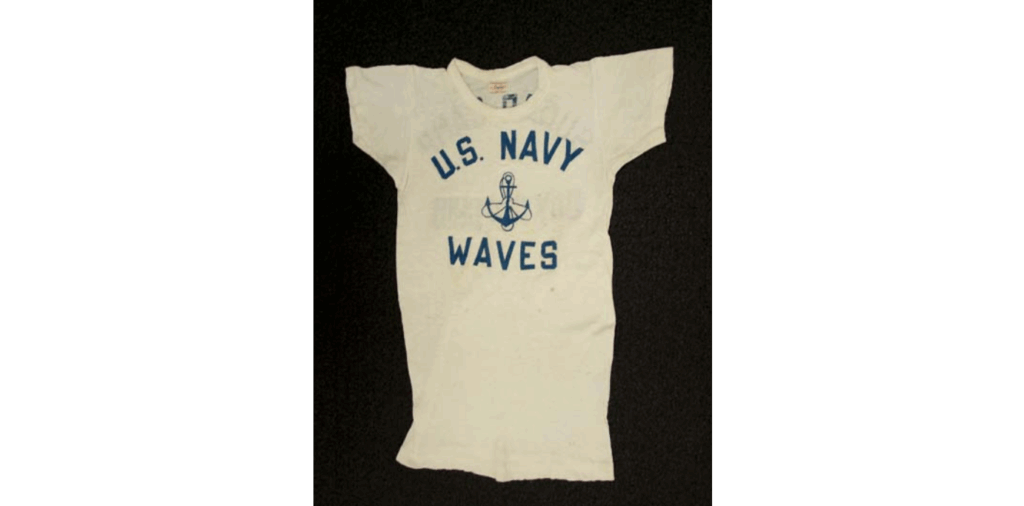

During WWII, a women’s reserve branch of the Navy was founded: the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services), which allowed women to enlist in the Navy and serve in non-combat roles. Approximately 100,000 women served in the WAVES during WWII. We are lucky enough to have items that belonged to a member of the WAVES who worked in cryptography, Petty Officer First Class Marjorie Rose Pollard. Research into PO1 Pollard’s service revealed that she may have been part of the LGBTQ+ community.

During WWII, many women felt the call to serve their country. Many women stated that, because a family member or loved one was serving in the war, they wanted to do their part as well. While women have always been a part of military support — as nurses, as spies, as clerks — WWII is the first time women were able to enlist in the US Military in large numbers. While the Army Nurse Corps and Navy Nurse Corps did exist, they functioned as their own entities that supported the Army and Navy. With the creation of branches like the Navy’s WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services) and the Army’s WAC (Women’s Army Corps), women were able to enlist in the military itself and serve as non-combat soldiers. These women served as translators, switchboard operators, aviation mechanics, cryptographers, and much more.

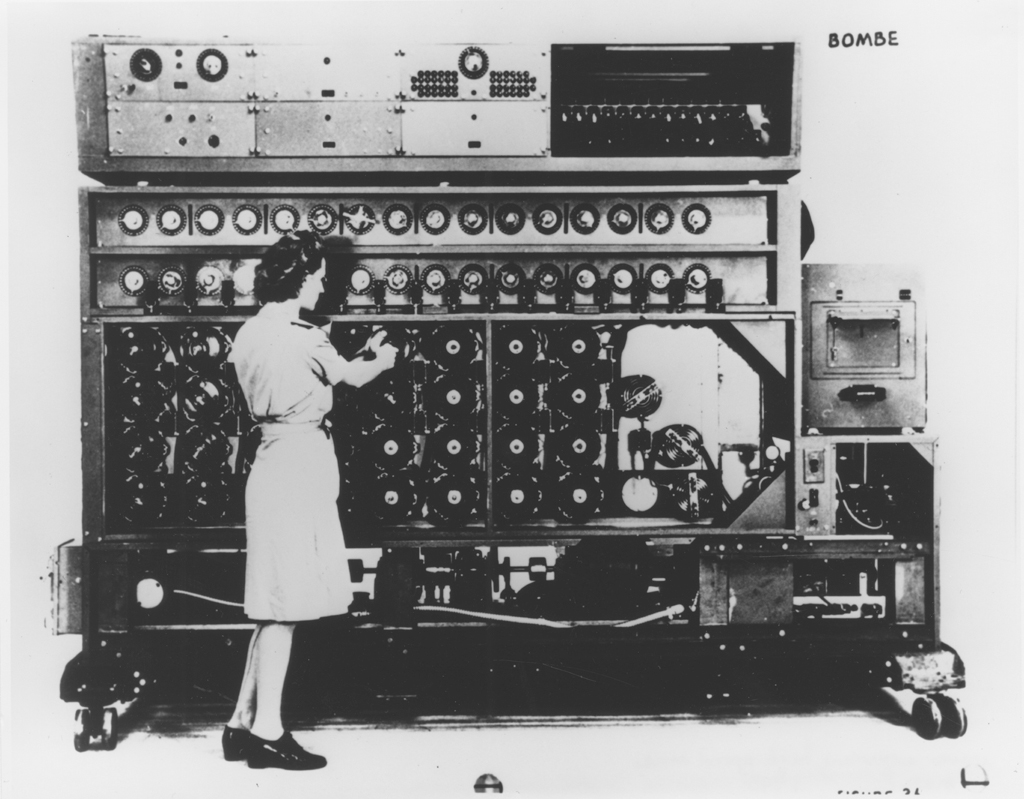

Before the US entered WWII, many people saw the need to involve women in the war effort. In 1941, US Navy Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes asked several women’s universities to host secret encryption classes for select students, with the idea that these women would work for the Navy to decode Axis messages after they graduated. Many of these women later enlisted in the WAVES, where they worked to manually decode Axis messages, build decryption machines called Bombes, and run Bombes to automatically decipher Axis messages.

During WWII, the German military had a huge advantage: the Enigma Machine. The Enigma was an encryption machine used by the German military to encrypt messages. It was said to produce an unbreakable code, because you needed both an Enigma machine and to know all the correct settings to decrypt its code. Polish, English, and American military worked to build and refine machines that could break Enigma code, which they called Bombes. The Bombes were 7’ high, 2’ wide, 10’ long, weighed 5,000 lbs each, and when programmed, they could decipher Axis code in hours rather than weeks when done by hand. So the US military decided to build as many Bombes as possible to decode messages as quickly as possible.

Sugar Camp at Dayton, Ohio, was selected as the location for building over 120 Bombes. The facility was owned by the National Cash Register Company and had not only facilities suited for building machinery, but also housing on-site for service members to live in while stationed there. Over 600 WAVES and 200 Navy servicemen were stationed at Sugar Camp, where they learned to build and run the Bombes. Each Bombe required 64 rotors to be wired to match the rotors actually used in the Germans’ Enigma. Each WAVE was given a wiring diagram for one side of the two-sided rotor. She spent her eight-hour shift soldering wires to rotors. Another WAVE soldered the other side. This arrangement maintained the secrecy of the rotor wirings. No WAVE would have knowledge of both sides of any rotor. The WAVES worked in three 8-hour shifts so that Bombes were being assembled and run 24 hours a day.

The Mariners’ Museum and Park’s Collection contains several uniform pieces, notes, records, and letters that belonged to PO1 Marjorie Rose Pollard, who worked in cryptography. Not only do we have several pieces of her uniform, but we also have letters sent between her and family members. Marjorie particularly corresponded with her father often, who was serving in the Army in the Pacific Theater.

We also have a number of her notes on cryptography and the construction of Bombe machines. These notes were likely taken while she was stationed at Sugar Camp, Dayton, Ohio, learning to assemble and run Bombes. Later, she was stationed at the Naval Communications station in Washington, DC, where WAVES ran Bombes day and night. The Navy’s decryption work helped plan D-Day, destroy U-boats, and much more. Estimates claim that WWII Allied code breakers shortened the war by up to two years.

When researching PO1 Marjorie Pollard, I hoped to learn a bit more about her life during and after the war. Was her work in the WAVES a life-changing experience for her? Did she struggle with the weight of the job, knowing that mistakes could lead to lives lost? Did she stay in the Navy after the war, or did she return to civilian life? Despite my best efforts, I didn’t find as much as I had hoped.

Pollard was born in 1923 in Kansas City, Missouri, and lived there until she enlisted in the WAVES in 1942. She started her WAVES career as a Seaman Apprentice, and she was honorably discharged as a Petty Officer First Class. After the war, she moved back to Kansas City and worked for many years as a telephone operator. I was starting to lose hope in finding more when I found a memorial for PO1 Pollard on Findagrave.com. The most intriguing part of the memorial was a photograph, which showed a plaque for Marjorie side by side with a plaque for another woman, Helen E. Emmert.

Helen E. Emmert was also from Kansas City, Missouri. During WWII, she volunteered with a group called Women of the War Chest, which ran fundraisers to support prisoners of war. Helen Emmert’s obituary was where the pieces of this puzzle started to fit together. The last sentence of her obituary states, “Survivors include nephews and nieces, and a companion, Marjorie Pollard of the home.” This leads me to believe that Marjorie Pollard and Helen Emmert were likely in a romantic relationship.

While members of the LGBTQ+ community absolutely existed in the 1940s and earlier, it was not something that was publicly spoken about. The military had written legislation against homosexuality among service men and women, even up until 2010. Despite this, many LGBTQ+ service members created their own space within the military, including lesbians and queer women in the WAVES. Many used slang and codes to identify themselves to other LGBTQ+ community members. The coded language was usually something that could be interpreted as a sign of platonic friendship, like singing a particular song, or referring to a romantic partner as a “companion of the home.”

This coded language was necessary because if a person’s orientation was discovered by the wrong person, it could have disastrous effects. The military provided regulations for the “undesirable discharge of homosexuals” for male and female service members. An oral account from another WAVE stationed at Sugar Camp, Dayton, Ohio, stated that there were two WAVES who were discovered to be in a romantic relationship, and they were both immediately discharged from the WAVES because of this. In fact, more than 9000 American service members were given a section 8 ‘blue discharge’ for being homosexual during WWII. And after the war, in 1953, President Eisenhower signed an Executive Order that banned homosexuals from federal employment, which led to 5,000 federal employees losing their jobs over accusations of homosexuality.

With the amount of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation during her lifetime, if PO1 Pollard was part of the LGBTQ+ community, she was likely very hesitant to openly admit it. While it is certainly possible that PO1 Marjorie Pollard and Helen Emmert were two platonic friends who lived together for the majority of their lives, it does seem more likely that they were two women in a long-term romantic relationship. During Pride Month, it is important to remember that veterans come from all walks of life and all backgrounds, including the LGBTQ+ community. Whether Marjorie Pollard was LGBTQ+ or not, she certainly made a significant contribution to both the war effort and women’s military history.

Sources:

- Women, Gender and World War II by Mellisa A. McEuen

- Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two by Allan Berube.

- “Dykes” or “Whores”: Sexuality and the Women’s Army Corps in the United States during World War II by Michaela Hampf

- Code Girls: the untold story of the American women code breakers of World War WWII by Liza Mundy

- Creating GI Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women’s Army Corps During World War II by Leisa D. Meyer

- My Country, My Right to Serve: Experiences of Gay Men and Women in the Military, World War II to the Present by Mary Ann Humphrey